Brahmi script facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brahmi |

|

|---|---|

[[Image: |200x400px]] |200x400px]]

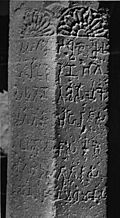

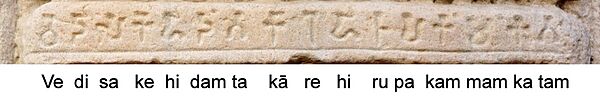

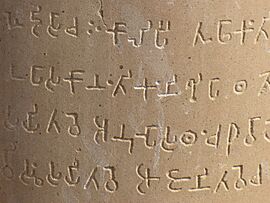

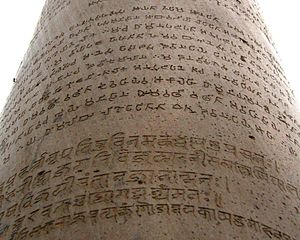

Brahmi script on Ashoka Pillar in Sarnath (c. 250 BCE)

|

|

| Type | Abugida |

| Spoken languages | Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit, Tamil, Saka, Tocharian, Telugu, Elu |

| Time period | At least by the 3rd century BCE to 5th century CE |

| Parent systems | |

| Child systems | Numerous descendant writing systems including:

Devanagari, Kaithi, Sylheti Nagri, Gujarati, Modi, Bengali, Assamese, Sharada, Tirhuta, Odia, Kalinga, Nepalese, Gurmukhi, Khudabadi, Multani, Dogri, Tocharian, Meitei, Lepcha, Tibetan, Bhaiksuki, Siddhaṃ, Takri, ʼPhags-pa |

| Sister systems | Kharosthi |

| Unicode range | U+11000–U+1107F |

| ISO 15924 | Brah |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/ BRAH-mee; 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻; ISO: Brāhmī) is a writing system of ancient India that appeared as a fully developed script in the 3rd century BCE. Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across Southern and Southeastern Asia.

Brahmi is an abugida which uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. The writing system only went through relatively minor evolutionary changes from the Mauryan period (3rd century BCE) down to the early Gupta period (4th century CE), and it is thought that as late as the 4th century CE, a literate person could still read and understand Mauryan inscriptions. Sometime thereafter, the ability to read the original Brahmi script was lost. The earliest (indisputably dated) and best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dating to 250–232 BCE.

The decipherment of Brahmi became the focus of European scholarly attention in the early 19th-century during East India Company rule in India, in particular in the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta. Brahmi was deciphered by James Prinsep, the secretary of the Society, in a series of scholarly articles in the Society's journal in the 1830s. His breakthroughs built on the epigraphic work of Christian Lassen, Edwin Norris, H. H. Wilson and Alexander Cunningham, among others.

The origin of the script is still much debated, with most scholars stating that Brahmi was derived from or at least influenced by one or more contemporary Semitic scripts. Some non-specialists favour the idea of an indigenous origin or connection to the much older and as yet undeciphered Indus script, although this is not generally accepted by epigraphists.

Brahmi was at one time referred to in English as the "pin-man" script, likening the characters to stick figures. It was known by a variety of other names, including "lath", "Laṭ", "Southern Aśokan", "Indian Pali" or "Mauryan" (Salomon 1998, p. 17), until the 1880s when Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, based on an observation by Gabriel Devéria, associated it with the Brahmi script, the first in a list of scripts mentioned in the Lalitavistara Sūtra. Thence the name was adopted in the influential work of Georg Bühler, albeit in the variant form "Brahma".

The Gupta script of the 5th century is sometimes called "Late Brahmi". From the 6th century onward, the Brahmi script diversified into numerous local variants, grouped as the Brahmic family of scripts. Dozens of modern scripts used across South and South East Asia have descended from Brahmi, making it one of the world's most influential writing traditions. One survey found 198 scripts that ultimately derive from it.

Among the inscriptions of Ashoka (c. 3rd century BCE) written in the Brahmi script a few numerals were found, which have come to be called the Brahmi numerals. The numerals are additive and multiplicative and, therefore, not place value; it is not known if their underlying system of numeration has a connection to the Brahmi script. But in the second half of the 1st millennium CE, some inscriptions in India and Southeast Asia written in scripts derived from the Brahmi did include numerals that are decimal place value, and constitute the earliest existing material examples of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, now in use throughout the world. The underlying system of numeration, however, was older, as the earliest attested orally transmitted example dates to the middle of the 3rd century CE in a Sanskrit prose adaptation of a lost Greek work on astrology.

Texts

The Brahmi script is mentioned in the ancient Indian texts of the three major Dharmic religions: Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, as well as their Chinese translations. For example, the 10th chapter of the Lalitavistara Sūtra (c. 200–300 CE), titled the Lipisala samdarshana parivarta, lists 64 lipi (scripts), with the Brahmi script starting the list. The Lalitavistara Sūtra states that young Siddhartha, the future Gautama Buddha (~500 BCE), mastered philology, Brahmi and other scripts from the Brahmin Lipikāra and Deva Vidyāsiṃha at a school.

A list of eighteen ancient scripts is found in the early Jaina texts, such as the Paṇṇavaṇā Sūtra (2nd century BCE) and the Samavāyāṅga Sūtra (3rd century BCE). These Jain script lists include Brahmi at number 1 and Kharoṣṭhi at number 4, but also Javanaliya (probably Greek) and others not found in the Buddhist lists.

Origins

While the contemporary Kharoṣṭhī script is widely accepted to be a derivation of the Aramaic alphabet, the genesis of the Brahmi script is less straightforward. Salomon reviewed existing theories in 1998, while Falk provided an overview in 1993.

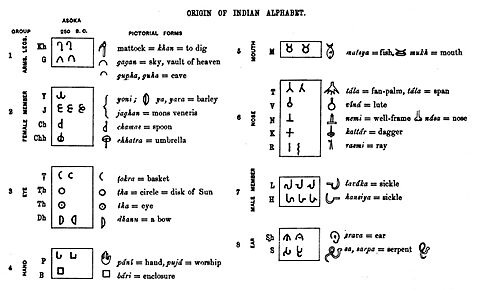

Early theories proposed a pictographic-acrophonic origin for the Brahmi script, on the model of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script. These ideas however have lost credence, as they are "purely imaginative and speculative". Similar ideas have tried to connect the Brahmi script with the Indus script, but they remain unproven, and particularly suffer from the fact that the Indus script is as yet undeciphered.

The mainstream view is that Brahmi has an origin in Semitic scripts (usually Aramaic). This is accepted by the vast majority of script scholars since the publications by Albrecht Weber (1856) and Georg Bühler's On the origin of the Indian Brahma alphabet (1895). Bühler's ideas have been particularly influential, though even by the 1895 date of his opus on the subject, he could identify no fewer than five competing theories of the origin, one positing an indigenous origin and the others deriving it from various Semitic models.

The most disputed point about the origin of the Brahmi script has long been whether it was a purely indigenous development or was borrowed or derived from scripts that originated outside India. Goyal (1979) noted that most proponents of the indigenous view are fringe Indian scholars, whereas the theory of Semitic origin is held by "nearly all" Western scholars, and Salomon agrees with Goyal that there has been "nationalist bias" and "imperialist bias" on the two respective sides of the debate. In spite of this, the view of indigenous development had been prevalent among British scholars writing prior to Bühler: a passage by Alexander Cunningham, one of the earliest indigenous origin proponents, suggests that, in his time, the indigenous origin was a preference of British scholars in opposition to the "unknown Western" origin preferred by continental scholars. Cunningham in the seminal Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum of 1877 speculated that Brahmi characters were derived from, among other things, a pictographic principle based on the human body, but Bühler noted that, by 1891, Cunningham considered the origins of the script uncertain.

Most scholars believe that Brahmi was likely derived from or influenced by a Semitic script model, with Aramaic being a leading candidate. However, the issue is not settled due to the lack of direct evidence and unexplained differences between Aramaic, Kharoṣṭhī, and Brahmi. Though Brahmi and the Kharoṣṭhī script share some general features, the differences between the Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts are "much greater than their similarities", and "the overall differences between the two render a direct linear development connection unlikely", states Richard Salomon.

Virtually all authors accept that regardless of the origins, the differences between the Indian script and those proposed to have influenced it are significant. The degree of Indian development of the Brahmi script in both the graphic form and the structure has been extensive. It is also widely accepted that theories about the grammar of the Vedic language probably had a strong influence on this development. Some authors – both Western and Indian – suggest that Brahmi was borrowed or inspired by a Semitic script, invented in a short few years during the reign of Ashoka, and then used widely for Ashokan inscriptions. In contrast, some authors reject the idea of foreign influence.

Bruce Trigger states that Brahmi likely emerged from the Aramaic script (with extensive local development), but there is no evidence of a direct common source. According to Trigger, Brahmi was in use before the Ashoka pillars, at least by the 4th or 5th century BCE in Sri Lanka and India, while Kharoṣṭhī was used only in northwest South Asia (eastern parts of modern Afghanistan and neighboring regions of Pakistan) for a while before it died out in the third century. According to Salomon, evidence of the use of Kharoṣṭhī is found primarily in Buddhist records and those of Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian, and Kushana dynasty era.

Justeson and Stephens proposed that this inherent vowel system in Brahmi and Kharoṣṭhī developed by transmission of a Semitic abjad through the recitation of its letter values. The idea is that learners of the source alphabet recite the sounds by combining the consonant with an unmarked vowel, e.g. /kə/, /kʰə/, /gə/, and in the process of borrowing into another language, these syllables are taken to be the sound values of the symbols. They also accepted the idea that Brahmi was based on a North Semitic model.

Semitic hypothesis

Many scholars link the origin of Brahmi to Semitic script models, particularly Aramaic. The explanation of how this might have happened, the particular Semitic script, and the chronology of the derivation have been the subject of much debate. Bühler followed Max Weber in connecting it particularly to Phoenician, and proposed an early 8th century BCE date for the borrowing. A link to the South Semitic scripts, a less prominent branch of the Semitic script family, has occasionally been proposed, but has not gained much acceptance. Finally, the Aramaic script being the prototype for Brahmi has been the more preferred hypothesis because of its geographic proximity to the Indian subcontinent, and its influence likely arising because Aramaic was the bureaucratic language of the Achaemenid empire. However, this hypothesis does not explain the mystery of why two very different scripts, Kharoṣṭhī and Brahmi, developed from the same Aramaic. A possible explanation might be that Ashoka created an imperial script for his edicts, but there is no evidence to support this conjecture.

The chart below shows the close resemblance that Brahmi has with the first four letters of Semitic script, the first column representing the Phoenician alphabet.

| Letter | Name | Phoneme | Origin | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Hieroglyphs | Proto-Sinaitic | Aramaic | Hebrew | Syriac | Greek | Brahmi | |||||||||

| 𐤀 | ʾālep | ʾ [ʔ] | 𓃾 | 𐡀 | א | ܐ | Αα | 𑀅 | |||||||||

| 𐤁 | bēt | b [b] | 𓉐 | 𐡁 | ב | ܒ | Ββ | 𑀩 | |||||||||

| 𐤂 | gīml | g [ɡ] | 𓌙 | 𐡂 | ג | ܓ | Γγ | 𑀕 | |||||||||

| 𐤃 | dālet | d [d] | 𓇯 | 𐡃 | ד | ܕ | Δδ | 𑀥 | |||||||||

Bühler's hypothesis

According to the Semitic hypothesis as laid out by Bühler in 1898, the oldest Brahmi inscriptions were derived from a Phoenician prototype. Salomon states Bühler's arguments are "weak historical, geographical, and chronological justifications for a Phoenician prototype". Discoveries made since Bühler's proposal, such as of six Mauryan inscriptions in Aramaic, suggest Bühler's proposal about Phoenician as weak. It is more likely that Aramaic, which was virtually certainly the prototype for Kharoṣṭhī, also may have been the basis for Brahmi. However, it is unclear why the ancient Indians would have developed two very different scripts.

| Phoenician | Aramaic | Value | Brahmi | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | a | |||

| b [b] | ba | |||

| g [ɡ] | ga | |||

| d [d] | dha | |||

| h [h], M.L. | ha | |||

| w [w], M.L. | va | |||

| z [z] | ja | |||

| ḥ [ħ] | gha | |||

| ṭ [tˤ] | tha | |||

| y [j], M.L. | ya | |||

| k [k] | ka | |||

| l [l] | la | |||

| m [m] | ma | |||

| n [n] | na | |||

| s [s] | ṣa | |||

| ʿ [ʕ], M.L. | e | |||

| p [p] | pa | |||

| ṣ [sˤ] | ca | |||

| q [q] | kha | |||

| r [r] | ra | |||

| š [ʃ] | śa | |||

| t [t] | ta |

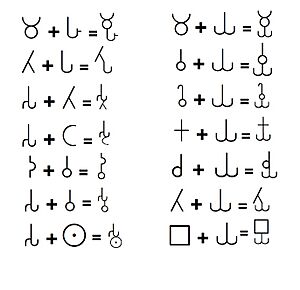

According to Bühler, Brahmi added symbols for certain sounds not found in Semitic languages, and either deleted or repurposed symbols for Aramaic sounds not found in Prakrit. For example, Aramaic lacks the phonetic retroflex feature that appears among Prakrit dental stops, such as ḍ, and in Brahmi the symbols of the retroflex and non-retroflex consonants are graphically very similar, as if both had been derived from a single prototype. (See Tibetan alphabet for a similar later development.) Aramaic did not have Brahmi's aspirated consonants (kh, th, etc.), whereas Brahmi did not have Aramaic's emphatic consonants (q, ṭ, ṣ), and it appears that these unneeded emphatic letters filled in for some of Brahmi's aspirates: Aramaic q for Brahmi kh, Aramaic ṭ (Θ) for Brahmi th (ʘ), etc. And just where Aramaic did not have a corresponding emphatic stop, p, Brahmi seems to have doubled up for the corresponding aspirate: Brahmi p and ph are graphically very similar, as if taken from the same source in Aramaic p. Bühler saw a systematic derivational principle for the other aspirates ch, jh, ph, bh, and dh, which involved adding a curve or upward hook to the right side of the character (which has been speculated to derive from h, ![]() ), while d and ṭ (not to be confused with the Semitic emphatic ṭ) were derived by back formation from dh and ṭh.

), while d and ṭ (not to be confused with the Semitic emphatic ṭ) were derived by back formation from dh and ṭh.

The attached table lists the correspondences between Brahmi and North Semitic scripts.

Bühler states that both Phoenician and Brahmi had three voiceless sibilants, but because the alphabetical ordering was lost, the correspondences among them are not clear. Bühler was able to suggest Brahmi derivatives corresponding to all of the 22 North Semitic characters, though clearly, as Bühler himself recognized, some are more confident than others. He tended to place much weight on phonetic congruence as a guideline, for example connecting c ![]() to tsade 𐤑 rather than kaph 𐤊, as preferred by many of his predecessors.

to tsade 𐤑 rather than kaph 𐤊, as preferred by many of his predecessors.

One of the key problems with a Phoenician derivation is the lack of evidence for historical contact with Phoenicians in the relevant period. Bühler explained this by proposing that the initial borrowing of Brahmi characters dates back considerably earlier than the earliest known evidence, as far back as 800 BCE, contemporary with the Phoenician glyph forms that he mainly compared. Bühler cited a near-modern practice of writing Brahmic scripts informally without vowel diacritics as a possible continuation of this earlier abjad-like stage in development.

The weakest forms of the Semitic hypothesis are similar to Gnanadesikan's trans-cultural diffusion view of the development of Brahmi and Kharoṣṭhī, in which the idea of alphabetic sound representation was learned from the Aramaic-speaking Persians, but much of the writing system was a novel development tailored to the phonology of Prakrit.

Further evidence cited in favor of Persian influence has been the Hultzsch proposal in 1925 that the Prakrit/Sanskrit word for writing itself, lipi is similar to the Old Persian word dipi, suggesting a probable borrowing. A few of the Ashoka edicts from the region nearest the Persian empire use dipi as the Prakrit word for writing, which appears as lipi elsewhere, and this geographic distribution has long been taken, at least back to Bühler's time, as an indication that the standard lipi form is a later alteration that appeared as it diffused away from the Persian sphere of influence. Persian dipi itself is thought to be an Elamite loanword.

Greek-Semitic model hypothesis

Falk's 1993 book Schrift im Alten Indien is a study on writing in ancient India, and has a section on the origins of Brahmi. It features an extensive review of the literature up to that time. Falk sees the basic writing system of Brahmi as being derived from the Kharoṣṭhī script, itself a derivative of Aramaic. At the time of his writing, the Ashoka edicts were the oldest confidently dateable examples of Brahmi, and he perceives in them "a clear development in language from a faulty linguistic style to a well honed one" over time, which he takes to indicate that the script had been recently developed. Falk deviates from the mainstream of opinion in seeing Greek as also being a significant source for Brahmi. On this point particularly, Salomon disagrees with Falk, and after presenting evidence of very different methodology between Greek and Brahmi notation of vowel quantity, he states "it is doubtful whether Brahmi derived even the basic concept from a Greek prototype". Further, adds Salomon, in a "limited sense Brahmi can be said to be derived from Kharosthi, but in terms of the actual forms of the characters, the differences between the two Indian scripts are much greater than the similarities".

Falk also dated the origin of Kharoṣṭhī to no earlier than 325 BCE, based on a proposed connection to the Greek conquest. Salomon questions Falk's arguments as to the date of Kharoṣṭhī and writes that it is "speculative at best and hardly constitutes firm grounds for a late date for Kharoṣṭhī. The stronger argument for this position is that we have no specimen of the script before the time of Ashoka, nor any direct evidence of intermediate stages in its development; but of course this does not mean that such earlier forms did not exist, only that, if they did exist, they have not survived, presumably because they were not employed for monumental purposes before Ashoka".

Unlike Bühler, Falk does not provide details of which and how the presumptive prototypes may have been mapped to the individual characters of Brahmi. Further, states Salomon, Falk accepts there are anomalies in phonetic value and diacritics in Brahmi script that are not found in the presumed Kharoṣṭhī script source. Falk attempts to explain these anomalies by reviving the Greek influence hypothesis, a hypothesis that had previously fallen out of favor.

Hartmut Scharfe, in his 2002 review of Kharoṣṭī and Brāhmī scripts, concurs with Salomon's questioning of Falk's proposal, and states, "the pattern of the phonemic analysis of the Sanskrit language achieved by the Vedic scholars is much closer to the Brahmi script than the Greek alphabet".

As of 2018, Harry Falk refined his view by affirming that Brahmi was developed from scratch in a rational way at the time of Ashoka, by consciously combining the advantages of the pre-existing Greek script and northern Kharosthi script. Greek-style letter types were selected for their "broad, upright and symmetrical form", and writing from left to right was also adopted for its convenience. On the other hand, the Kharosthi treatment of vowels was retained, with its inherent vowel "a", derived from Aramaic, and stroke additions to represent other vowel signs. In addition, a new system of combining consonants vertically to represent complex sounds was also developed.

Indigenous origin hypothesis

The possibility of an indigenous origin such as a connection to the Indus script is supported by some Western and Indian scholars and writers. The theory that there are similarities to the Indus script was suggested by early European scholars such as the archaeologist John Marshall and the Assyriologist Stephen Langdon. G. R. Hunter in his book The Script of Harappa and Mohenjodaro and Its Connection with Other Scripts (1934) proposed a derivation of the Brahmi alphabets from the Indus script, the match being considerably higher than that of Aramaic in his estimation. British archaeologist Raymond Allchin stated that there is a powerful argument against the idea that the Brahmi script has Semitic borrowing because the whole structure and conception is quite different. He at one time suggested that the origin may have been purely indigenous with the Indus script as its predecessor. However, Allchin and Erdosy later in 1995 expressed the opinion that there was as yet insufficient evidence to resolve the question.

Today the indigenous origin hypothesis is more commonly promoted by non-specialists, such as the computer scientist Subhash Kak, the spiritual teachers David Frawley and Georg Feuerstein, and the social anthropologist Jack Goody. Subhash Kak disagrees with the proposed Semitic origins of the script, instead stating that the interaction between the Indic and the Semitic worlds before the rise of the Semitic scripts might imply a reverse process. However, the chronology thus presented and the notion of an unbroken tradition of literacy is opposed by a majority of academics who support an indigenous origin. Evidence for a continuity between Indus and Brahmi has also been seen in graphic similarities between Brahmi and the late Indus script, where the ten most common ligatures correspond with the form of one of the ten most common glyphs in Brahmi. There is also corresponding evidence of continuity in the use of numerals. Further support for this continuity comes from statistical analysis of the relationship carried out by Das.

Salomon considered simple graphic similarities between characters to be insufficient evidence for a connection without knowing the phonetic values of the Indus script, though he found apparent similarities in patterns of compounding and diacritical modification to be "intriguing". However, he felt that it was premature to explain and evaluate them due to the large chronological gap between the scripts and the thus far indecipherable nature of the Indus script.

The main obstacle to this idea is the lack of evidence for writing during the millennium and a half between the collapse of the Indus Valley civilisation around 1500 BCE and the first widely accepted appearance of Brahmi in the 3rd or 4th centuries BCE. Iravathan Mahadevan makes the point that even if one takes the latest dates of 1500 BCE for the Indus script and earliest claimed dates of Brahmi around 500 BCE, a thousand years still separates the two. Furthermore, there is no accepted decipherment of the Indus script, which makes theories based on claimed decipherments tenuous.

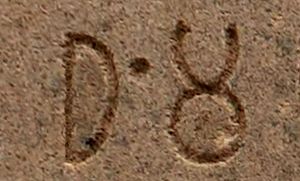

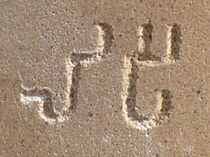

A promising possible link between the Indus script and later writing traditions may be in the megalithic graffiti symbols of the South Indian megalithic culture, which may have some overlap with the Indus symbol inventory and persisted in use up at least through the appearance of the Brahmi and scripts up into the third century CE. These graffiti usually appear singly, though on occasion may be found in groups of two or three, and are thought to have been family, clan, or religious symbols. In 1935, C. L. Fábri proposed that symbols found on Mauryan punch-marked coins were remnants of the Indus script that had survived the collapse of the Indus civilization.

Another form of the indigenous origin theory is that Brahmi was invented ex nihilo, entirely independently from either Semitic models or the Indus script, though Salomon found these theories to be wholly speculative in nature.

Foreign origination

𑀮La+𑀺i; pī=𑀧Pa+𑀻ii). The word would be of Old Persian origin ("Dipi").Pāṇini (6th to 4th century BCE) mentions lipi, the Indian word for writing scripts in his definitive work on Sanskrit grammar, the Ashtadhyayi. According to Scharfe, the words lipi and libi are borrowed from the Old Persian dipi, in turn derived from Sumerian dup. To describe his own Edicts, Ashoka used the word Lipī, now generally simply translated as "writing" or "inscription". It is thought the word "lipi", which is also orthographed "dipi" in the two Kharosthi-version of the rock edicts, comes from an Old Persian prototype dipî also meaning "inscription", which is used for example by Darius I in his Behistun inscription, suggesting borrowing and diffusion.

Scharfe adds that the best evidence is that no script was used or ever known in India, aside from the Persian-dominated Northwest where Aramaic was used, before around 300 BCE because Indian tradition "at every occasion stresses the orality of the cultural and literary heritage", yet Scharfe in the same book admits that "a script has been discovered in the excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization that flourished in the Indus valley and adjacent areas in the third millennium B.C. The number of different signs suggest a syllabic script, but all attempts at decipherment have been unsuccessful so far. Attempts by some Indian scholars to connect this undeciphered script with the Indian scripts in vogue from the third century B.C. onward are total failures."

Megasthenes' observations

Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador to the Mauryan court in Northeastern India only a quarter century before Ashoka, noted "... and this among a people who have no written laws, who are ignorant even of writing, and regulate everything by memory." This has been variously and contentiously interpreted by many authors. Ludo Rocher almost entirely dismisses Megasthenes as unreliable, questioning the wording used by Megasthenes' informant and Megasthenes' interpretation of them. Timmer considers it to reflect a misunderstanding that the Mauryans were illiterate "based upon the fact that Megasthenes rightly observed that the laws were unwritten and that oral tradition played such an important part in India."

Some proponents of the indigenous origin theories question the reliability and interpretation of comments made by Megasthenes (as quoted by Strabo in the Geographica XV.i.53). For one, the observation may only apply in the context of the kingdom of "Sandrakottos" (Chandragupta). Elsewhere in Strabo (Strab. XV.i.39), Megasthenes is said to have noted that it was a regular custom in India for the "philosopher" caste (presumably Brahmins) to submit "anything useful which they have committed to writing" to kings, but this detail does not appear in parallel extracts of Megasthenes found in Arrian and Diodorus Siculus. The implication of writing per se is also not totally clear in the original Greek as the term "συντάξῃ" (source of the English word "syntax") can be read as a generic "composition" or "arrangement", rather than a written composition in particular. Nearchus, a contemporary of Megasthenes, noted, a few decades prior, the use of cotton fabric for writing in Northern India. Indologists have variously speculated that this might have been Kharoṣṭhī or the Aramaic alphabet. Salomon regards the evidence from Greek sources to be inconclusive. Strabo himself notes this inconsistency regarding reports on the use of writing in India (XV.i.67).

Debate on time depth

Kenneth Norman (2005) suggests that Brahmi was devised over a longer period of time predating Ashoka's rule:

Support for this idea of pre-Ashokan development has been given very recently by the discovery of sherds at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, inscribed with small numbers of characters which seem to be Brāhmī. These sherds have been dated, by both Carbon 14 and Thermo-luminescence dating, to pre-Ashokan times, perhaps as much as two centuries before Ashoka.

However, these finds are controversial, see Brahmi script § Notes.

He also notes that the variations seen in the Asokan edicts would be unlikely to have emerged so quickly if Brahmi had a single origin in the chancelleries of the Mauryan Empire. He suggests a date of not later than the end of the 4th century for the development of Brahmi script in the form represented in the inscriptions, with earlier possible antecedents.

Jack Goody (1987) had similarly suggested that ancient India likely had a "very old culture of writing" along with its oral tradition of composing and transmitting knowledge, because the Vedic literature is too vast, consistent and complex to have been entirely created, memorized, accurately preserved and spread without a written system.

Opinions on this point, the possibility that there may not have been any writing scripts including Brahmi during the Vedic age, given the quantity and quality of the Vedic literature, are divided. While Falk (1993) disagrees with Goody, while Walter Ong and John Hartley (2012) concur, not so much based on the difficulty of orally preserving the Vedic hymns, but on the basis that it is highly unlikely that Panini's grammar was composed. Johannes Bronkhorst (2002) takes the intermediate position that the oral transmission of the Vedic hymns may well have been achieved orally, but that the development of Panini's grammar presupposes writing (consistent with a development of Indian writing in c. the 4th century BCE).

Origin of the name

Several divergent accounts of the origin of the name "Brahmi" (ब्राह्मी) appear in history. The term Brahmi (बाम्भी in original) appears in Indian texts in different contexts. According to the rules of the Sanskrit language, it is a feminine word which literally means "of Brahma" or "the female energy of the Brahman". In popular Hindu texts such as the Mahabharata, it appears in the sense of a goddess, particularly for Saraswati as the goddess of speech and elsewhere as "personified Shakti (energy) of Brahma, the god of Hindu scriptures Veda and creation". Later Chinese Buddhist account of the 6th century CE also supports its creation to the god Brahma, though Monier Monier-Williams, Sylvain Lévi and others thought it was more likely to have been given the name because it was moulded by the Brahmins.

Alternatively, some Buddhist sutras such as the Lalitavistara Sūtra (possibly 4th century CE), list Brāhmī and Kharoṣṭī as some of the sixty-four scripts the Buddha knew as a child. Several sutras of Jainism such as the Vyakhya Pragyapti Sutra, the Samvayanga Sutra and the Pragyapna Sutra of the Jain Agamas include a list of 18 writing scripts known to teachers before the Mahavira was born, the first one being Bambhi (बाम्भी) in the original Prakrit, which has been interpreted as "Bramhi". The Brahmi script is missing from the list of 18 scripts in the surviving versions of two later Jaina Sutras, namely the Vishesha Avashyaka and the Kalpa Sutra. Jain legend recounts that 18 writing scripts were taught by their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha to his daughter Bambhi (बाम्भी); she emphasized बाम्भी as the main script as she taught others, and therefore the name Brahmi for the script comes after her name. There is no early epigraphic proof for the expression "Brahmi script". Ashoka himself when he created the first known inscriptions in the new script in the 3rd century BCE, used the expression dhaṃma lipi (Prakrit in the Brahmi script: 𑀥𑀁𑀫𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺, "Inscriptions of the Dharma") but this is not to describe the script of his own Edicts.

History

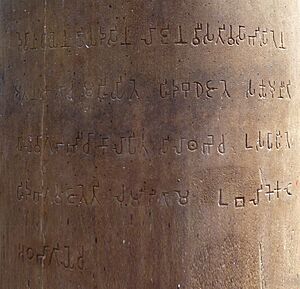

The earliest known full inscriptions of Brahmi are in Prakrit, dated to be from the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE, particularly the Edicts of Ashoka, c. 250 BCE. Prakrit records predominate the epigraphic records discovered in the Indian subcontinent through about the 1st century CE. The earliest known Brahmi inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st century BCE, such as the few discovered in Ayodhya, Ghosundi and Hathibada (both near Chittorgarh). Ancient inscriptions have also been discovered in many North and Central Indian sites, occasionally in South India as well, that are in hybrid Sanskrit-Prakrit language called "Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit". These are dated by modern techniques to between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. Surviving ancient records of the Brahmi script are found as engravings on pillars, temple walls, metal plates, terracotta, coins, crystals and manuscripts.

One of the most important recent developments regarding the origin of Brahmi has been the discovery of Brahmi characters inscribed on fragments of pottery from the trading town of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, which have been dated to between the 6th and the early 4th century BCE, although these finds are controversial (see Brahmi script § Notes). In 1996, Coningham et al. stated that the script on the Anuradhapura inscriptions is Brahmi, but stated that the language was a Prakrit rather than a Dravidian language. The historical sequence of the specimens was interpreted to indicate an evolution in the level of stylistic refinement over several centuries, and they concluded that the Brahmi script may have arisen out of "mercantile involvement" and that the growth of trade networks in Sri Lanka was correlated with its first appearance in the area. Salomon in his 1998 review states that the Anuradhapura inscriptions support the theory that Brahmi existed in South Asia before the Mauryan times, with studies favoring the 4th century BCE, but some doubts remain whether the inscriptions might be intrusive into the potsherds from a later date. Indologist Harry Falk has argued that the Edicts of Ashoka represent an older stage of Brahmi, whereas certain paleographic features of even the earliest Anuradhapura inscriptions are likely to be later, and so these potsherds may date from after 250 BCE.

More recently in 2013, Rajan and Yatheeskumar published excavations at Porunthal and Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu, where numerous both Tamil-Brahmi and "Prakrit-Brahmi" inscriptions and fragments have been found. Their stratigraphic analysis combined with radiocarbon dates of paddy grains and charcoal samples indicated that inscription contexts date to as far back as the 6th and perhaps 7th centuries BCE. As these were published very recently, they have as yet not been commented on extensively in the literature. Indologist Harry Falk has criticized Rajan's claims as "particularly ill-informed"; Falk argues that some of the earliest supposed inscriptions are not Brahmi letters at all, but merely misinterpreted non-linguistic Megalithic graffiti symbols, which were used in South India for several centuries during the pre-literate era.

Calligraphical evolution (3rd century BCE - 1st century CE)

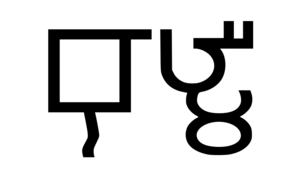

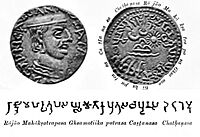

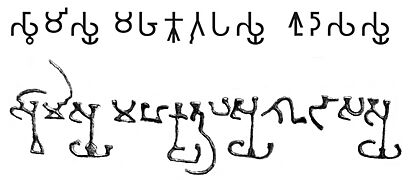

The text is Svāmisya Mahakṣatrapasya Śudasasya

"Of the Lord and Great Satrap Śudāsa"

The calligraphy of the Brahmi script remained virtually unchanged from the time of the Maurya Empire to the end of the 1st century BCE. Around this time, the Indo-Scythians ("Northern Satraps"), after their establishment in northern India introduced "revolutionary changes" in the way Brahmi was written. In the 1st century BCE, the shape of Brahmi characters became more angular, and the vertical segments of letters were equalized, a phenomenon which is clearly visible in coin legends and made the script visually more similarly to the Greek script. In this new typeface, the letter were "neat and well-formed". The probable introduction of ink and pen writing, with the characteristic thickenned start of each stroke generated by the usage of ink, was reproduced in the calligraphy of stone inscriptions by the creation of a triangle-shaped form at the beginning of each stroke. This new writing style is particularly visible in the numerous dedicatory inscriptions made in Mathura, in association with devotional works of art. This new calligraphy of the Brahmi script was adopted in the rest of the subcontinent of the next half century. The "new-pen-style" initiated a rapid evolution of the script from the 1st century CE, with regional variations starting to emerge.

Decipherment

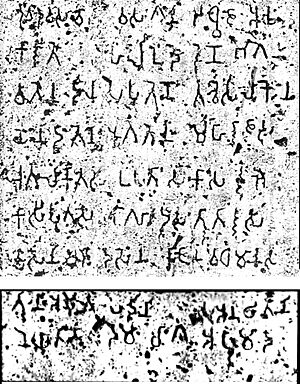

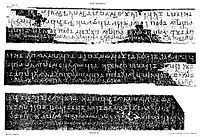

Besides a few inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic (which were only discovered in the 20th century), the Edicts of Ashoka were written in the Brahmi script and sometimes in the Kharoshthi script in the northwest, which had both become extinct around the 4th century CE, and were yet undeciphered at the time the Edicts were discovered and investigated in the 19th century.

Inscriptions of the 6th century CE in late Brahmi were already deciphered in 1785 by Charles Wilkins, who published an essentially correct translation of the Gopika Cave Inscription written by the Maukhari king Anantavarman. Wilkins seems to have relied essentially on the similarities with later Brahmic scripts, such as the script of the Pala period and early forms of Devanagari.

Early Brahmi, however, remained unreadable. Progress resumed in 1834 with the publication of proper facsimiles of the inscriptions on the Allahabad pillar of Ashoka, notably containing Edicts of Ashoka as well as inscriptions by the Gupta Empire ruler Samudragupta.

James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company, started to analyse the inscriptions and made deductions on the general characteristics of the early Brahmi script essentially relying on statistical methods. This method, published in March 1834, allowed him to classify the characters found in inscriptions, and to clarify the structure of Brahmi as being composed of consonantal characters with vocalic "inflections". He was able to correctly guess four out of five vocalic inflections, but the value of consonants remained unknown. Although this statistical method was modern and innovative, the actual decipherment of the script would have to wait until after the discovery of bilingual inscriptions, a few years later.

The same year, in 1834, some attempts by Rev. J. Stevenson were made to identify intermediate early Brahmi characters from the Karla Caves (c. 1st century CE) based on their similarities with the Gupta script of the Samudragupta inscription of the Allahabad pillar (4th century CE) which had just been published, but this led to a mix of good (about 1/3) and bad guesses, which did not permit proper decipherment of the Brahmi.

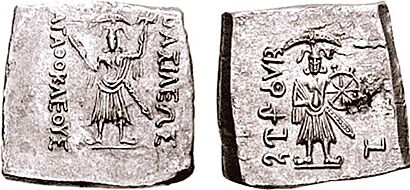

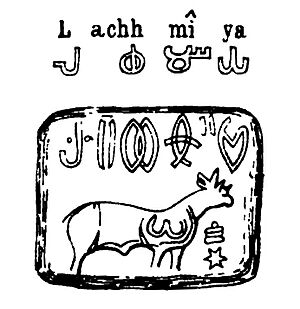

The next major step towards deciphering the ancient Brahmi script of the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE was made in 1836 by Norwegian scholar Christian Lassen, who used a bilingual Greek-Brahmi coin of Indo-Greek king Agathocles and similarities with the Pali script to correctly and securely identify several Brahmi letters. The matching legends on the bilingual coins of Agathocles were:

Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ / ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ (Basileōs Agathokleous, "of King Agathocles")

Brahmi legend:𑀭𑀚𑀦𑁂 / 𑀅𑀕𑀣𑀼𑀼𑀓𑁆𑀮𑁂𑀬𑁂𑀲 (Rajane Agathukleyesa, "King Agathocles").

James Prinsep was then able to complete the decipherment of the Brahmi script. After acknowledging Lassen's first decipherment, Prinsep used a bilingual coin of Indo-Greek king Pantaleon to decipher a few more letters. James Prinsep then analysed a large number of donatory inscriptions on the reliefs in Sanchi, and noted that most of them ended with the same two Brahmi characters: "𑀤𑀦𑀁". Prinsep guessed correctly that they stood for "danam", the Sanskrit word for "gift" or "donation", which permitted to further increase the number of known letters. With the help of Ratna Pâla, a Singhalese Pali scholar and linguist, Prinsep then completed the full decipherment of the Brahmi script. In a series of results that he published in March 1838 Prinsep was able to translate the inscriptions on a large number of rock edicts found around India, and provide, according to Richard Salomon, a "virtually perfect" rendering of the full Brahmi alphabet.

Southern Brahmi

Ashokan inscriptions are found all over India and a few regional variants have been observed. The Bhattiprolu alphabet, with earliest inscriptions dating from a few decades of Ashoka's reign, is believed to have evolved from a southern variant of the Brahmi alphabet. The language used in these inscriptions, nearly all of which have been found upon Buddhist relics, is exclusively Prakrit, though Kannada and Telugu proper names have been identified in some inscriptions. Twenty-three letters have been identified. The letters ga and sa are similar to Mauryan Brahmi, while bha and da resemble those of modern Kannada and Telugu script.

Tamil-Brahmi is a variant of the Brahmi alphabet that was in use in South India by about the 3rd century BCE, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Inscriptions attest their use in parts of Sri Lanka in the same period. The language used in around 70 Southern Brahmi inscriptions discovered in the 20th century have been identified as a Prakrit language.

In English, the most widely available set of reproductions of Brahmi texts found in Sri Lanka is Epigraphia Zeylanica; in volume 1 (1976), many of the inscriptions are dated to the 3rd–2nd century BCE.

Unlike the edicts of Ashoka, however, the majority of the inscriptions from this early period in Sri Lanka are found above caves. The language of Sri Lanka Brahmi inscriptions has been mostly been Prakrit though some Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions have also been found, such as the Annaicoddai seal. The earliest widely accepted examples of writing in Brahmi are found in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.

Red Sea and Southeast Asia

The Khuan Luk Pat inscription discovered in Thailand is in Tamil Brahmi script. Its date is uncertain and has been proposed to be from the early centuries of the common era. According to Frederick Asher, Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on potsherds have been found in Quseir al-Qadim and in Berenike, Egypt which suggest that merchant and trade activity was flourishing in ancient times between India and the Red Sea region. Additional Tamil Brahmi inscription has been found in Khor Rori region of Oman on an archaeological site storage jar.

Characteristics

Brahmi is usually written from left to right, as in the case of its descendants. However, an early coin found in Eran is inscribed with Brahmi running from right to left, as in Aramaic. Several other instances of variation in the writing direction are known, though directional instability is fairly common in ancient writing systems.

Consonants

Brahmi is an abugida, meaning that each letter represents a consonant, while vowels are written with obligatory diacritics called mātrās in Sanskrit, except when the vowels begin a word. When no vowel is written, the vowel /a/ is understood. This "default short a" is a characteristic shared with Kharosthī, though the treatment of vowels differs in other respects.

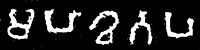

Conjunct consonants

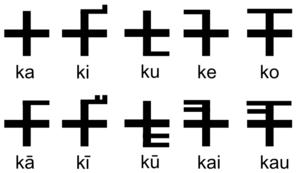

Special conjunct consonants are used to write consonant clusters such as /pr/ or /rv/. In modern Devanagari the components of a conjunct are written left to right when possible (when the first consonant has a vertical stem that can be removed at the right), whereas in Brahmi characters are joined vertically downwards.

-

Kya (vertical assembly of consonants "Ka"

and "Ya"

and "Ya"  ), as in "Sa-kya-mu-nī " ( 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻, "Sage of the Shakyas")

), as in "Sa-kya-mu-nī " ( 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀻, "Sage of the Shakyas")

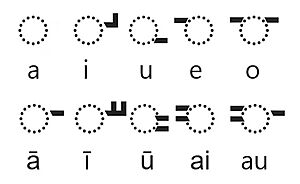

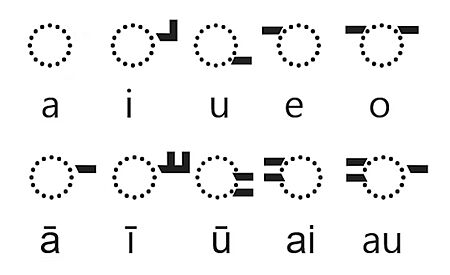

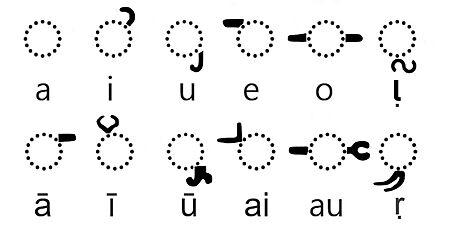

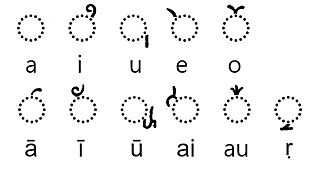

Vowels

Vowels following a consonant are inherent or written by diacritics, but initial vowels have dedicated letters. There are three "primary" vowels in Ashokan Brahmi, which each occur in length-contrasted forms: /a/, /i/, /u/; long vowels are derived from the letters for short vowels. There are also four "secondary" vowels that do not have the long-short contrast, /e:/, /ai/, /o:/, /au/. Note though that the grapheme for /ai/ is derivative from /e/ in a way which parallels the short-long contrast of the primary vowels (historically they were /ai/ and /a:i/). However, there are only nine distinct vowel diacritics, as short /a/ is understood if no vowel is written. The initial vowel symbol for /au/ is also apparently lacking in the earliest attested phases, even though it has a diacritic. Ancient sources suggest that there were either 11 or 12 vowels enumerated at the beginning of the character list around the Ashokan era, probably adding either aṃ or aḥ. Later versions of Brahmi add vowels for four syllabic liquids, short and long /ṛ/ and /ḷ/. Chinese sources indicate that these were later inventions by either Nagarjuna or Śarvavarman, a minister of King Hāla.

It has been noted that the basic system of vowel marking common to Brahmi and Kharosthī, in which every consonant is understood to be followed by a vowel, was well suited to Prakrit, but as Brahmi was adapted to other languages, a special notation called the virāma was introduced to indicate the omission of the final vowel. Kharoṣṭhī also differs in that the initial vowel representation has a single generic vowel symbol that is differentiated by diacritics, and long vowels are not distinguished.

The collation order of Brahmi is believed to have been the same as most of its descendant scripts, one based on Shiksha, the traditional Vedic theory of Sanskrit phonology. This begins the list of characters with the initial vowels (starting with a), then lists a subset of the consonants in five phonetically related groups of five called vargas, and ends with four liquids, three sibilants, and a spirant. Thomas Trautmann attributes much of the popularity of the Brahmic script family to this "splendidly reasoned" system of arrangement.

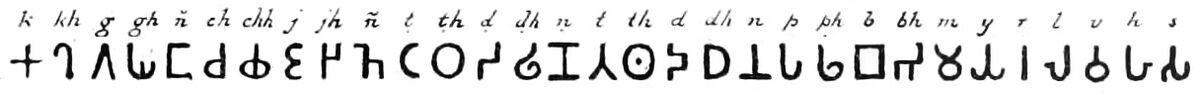

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | ḷ- | |

| -a | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 |

| -ā | 𑀓𑀸 | 𑀔𑀸 | 𑀕𑀸 | 𑀖𑀸 | 𑀗𑀸 | 𑀘𑀸 | 𑀙𑀸 | 𑀚𑀸 | 𑀛𑀸 | 𑀜𑀸 | 𑀝𑀸 | 𑀞𑀸 | 𑀟𑀸 | 𑀠𑀸 | 𑀡𑀸 | 𑀢𑀸 | 𑀣𑀸 | 𑀤𑀸 | 𑀥𑀸 | 𑀦𑀸 | 𑀧𑀸 | 𑀨𑀸 | 𑀩𑀸 | 𑀪𑀸 | 𑀫𑀸 | 𑀬𑀸 | 𑀭𑀸 | 𑀮𑀸 | 𑀯𑀸 | 𑀰𑀸 | 𑀱𑀸 | 𑀲𑀸 | 𑀳𑀸 | 𑀴𑀸 |

| -i | 𑀓𑀺 | 𑀔𑀺 | 𑀕𑀺 | 𑀖𑀺 | 𑀗𑀺 | 𑀘𑀺 | 𑀙𑀺 | 𑀚𑀺 | 𑀛𑀺 | 𑀜𑀺 | 𑀝𑀺 | 𑀞𑀺 | 𑀟𑀺 | 𑀠𑀺 | 𑀡𑀺 | 𑀢𑀺 | 𑀣𑀺 | 𑀤𑀺 | 𑀥𑀺 | 𑀦𑀺 | 𑀧𑀺 | 𑀨𑀺 | 𑀩𑀺 | 𑀪𑀺 | 𑀫𑀺 | 𑀬𑀺 | 𑀭𑀺 | 𑀮𑀺 | 𑀯𑀺 | 𑀰𑀺 | 𑀱𑀺 | 𑀲𑀺 | 𑀳𑀺 | 𑀴𑀺 |

| -ī | 𑀓𑀻 | 𑀔𑀻 | 𑀕𑀻 | 𑀖𑀻 | 𑀗𑀻 | 𑀘𑀻 | 𑀙𑀻 | 𑀚𑀻 | 𑀛𑀻 | 𑀜𑀻 | 𑀝𑀻 | 𑀞𑀻 | 𑀟𑀻 | 𑀠𑀻 | 𑀡𑀻 | 𑀢𑀻 | 𑀣𑀻 | 𑀤𑀻 | 𑀥𑀻 | 𑀦𑀻 | 𑀧𑀻 | 𑀨𑀻 | 𑀩𑀻 | 𑀪𑀻 | 𑀫𑀻 | 𑀬𑀻 | 𑀭𑀻 | 𑀮𑀻 | 𑀯𑀻 | 𑀰𑀻 | 𑀱𑀻 | 𑀲𑀻 | 𑀳𑀻 | 𑀴𑀻 |

| -u | 𑀓𑀼 | 𑀔𑀼 | 𑀕𑀼 | 𑀖𑀼 | 𑀗𑀼 | 𑀘𑀼 | 𑀙𑀼 | 𑀚𑀼 | 𑀛𑀼 | 𑀜𑀼 | 𑀝𑀼 | 𑀞𑀼 | 𑀟𑀼 | 𑀠𑀼 | 𑀡𑀼 | 𑀢𑀼 | 𑀣𑀼 | 𑀤𑀼 | 𑀥𑀼 | 𑀦𑀼 | 𑀧𑀼 | 𑀨𑀼 | 𑀩𑀼 | 𑀪𑀼 | 𑀫𑀼 | 𑀬𑀼 | 𑀭𑀼 | 𑀮𑀼 | 𑀯𑀼 | 𑀰𑀼 | 𑀱𑀼 | 𑀲𑀼 | 𑀳𑀼 | 𑀴𑀼 |

| -ū | 𑀓𑀽 | 𑀔𑀽 | 𑀕𑀽 | 𑀖𑀽 | 𑀗𑀽 | 𑀘𑀽 | 𑀙𑀽 | 𑀚𑀽 | 𑀛𑀽 | 𑀜𑀽 | 𑀝𑀽 | 𑀞𑀽 | 𑀟𑀽 | 𑀠𑀽 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑀽 | 𑀣𑀽 | 𑀤𑀽 | 𑀥𑀽 | 𑀦𑀽 | 𑀧𑀽 | 𑀨𑀽 | 𑀩𑀽 | 𑀪𑀽 | 𑀫𑀽 | 𑀬𑀽 | 𑀭𑀽 | 𑀮𑀽 | 𑀯𑀽 | 𑀰𑀽 | 𑀱𑀽 | 𑀲𑀽 | 𑀳𑀽 | 𑀴𑀽 |

| -e | 𑀓𑁂 | 𑀔𑁂 | 𑀕𑁂 | 𑀖𑁂 | 𑀗𑁂 | 𑀘𑁂 | 𑀙𑁂 | 𑀚𑁂 | 𑀛𑁂 | 𑀜𑁂 | 𑀝𑁂 | 𑀞𑁂 | 𑀟𑁂 | 𑀠𑁂 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁂 | 𑀣𑁂 | 𑀤𑁂 | 𑀥𑁂 | 𑀦𑁂 | 𑀧𑁂 | 𑀨𑁂 | 𑀩𑁂 | 𑀪𑁂 | 𑀫𑁂 | 𑀬𑁂 | 𑀭𑁂 | 𑀮𑁂 | 𑀯𑁂 | 𑀰𑁂 | 𑀱𑁂 | 𑀲𑁂 | 𑀳𑁂 | 𑀴𑁂 |

| -o | 𑀓𑁄 | 𑀔𑁄 | 𑀕𑁄 | 𑀖𑁄 | 𑀗𑁄 | 𑀘𑁄 | 𑀙𑁄 | 𑀚𑁄 | 𑀛𑁄 | 𑀜𑁄 | 𑀝𑁄 | 𑀞𑁄 | 𑀟𑁄 | 𑀠𑁄 | 𑀡 | 𑀢𑁄 | 𑀣𑁄 | 𑀤𑁄 | 𑀥𑁄 | 𑀦𑁄 | 𑀧𑁄 | 𑀨𑁄 | 𑀩𑁄 | 𑀪𑁄 | 𑀫𑁄 | 𑀬𑁄 | 𑀭𑁄 | 𑀮𑁄 | 𑀯𑁄 | 𑀰𑁄 | 𑀱𑁄 | 𑀲𑁄 | 𑀳𑁄 | 𑀴𑁄 |

| -Ø | 𑀓𑁆 | 𑀔𑁆 | 𑀕𑁆 | 𑀖𑁆 | 𑀗𑁆 | 𑀘𑁆 | 𑀙𑁆 | 𑀚𑁆 | 𑀛𑁆 | 𑀜𑁆 | 𑀝𑁆 | 𑀞𑁆 | 𑀟𑁆 | 𑀠𑁆 | 𑀡𑁆 | 𑀢𑁆 | 𑀣𑁆 | 𑀤𑁆 | 𑀥𑁆 | 𑀦𑁆 | 𑀧𑁆 | 𑀨𑁆 | 𑀩𑁆 | 𑀪𑁆 | 𑀫𑁆 | 𑀬𑁆 | 𑀭𑁆 | 𑀮𑁆 | 𑀯𑁆 | 𑀰𑁆 | 𑀱𑁆 | 𑀲𑁆 | 𑀳𑁆 | 𑀴𑁆 |

Punctuation

Punctuation can be perceived as more of an exception than as a general rule in Asokan Brahmi. For instance, distinct spaces in between the words appear frequently in the pillar edicts but not so much in others. ("Pillar edicts" refers to the texts that are inscribed on the stone pillars oftentimes with the intention of making them public.) The idea of writing each word separately was not consistently used.

In the early Brahmi period, the existence of punctuation marks is not very well shown. Each letter has been written independently with some occasional space between words and longer sections.

In the middle period, the system seems to be developing. The use of a dash and a curved horizontal line is found. A lotus (flower) mark seems to mark the end, and a circular mark appears to indicate the full stop. There seem to be varieties of full stop.

In the late period, the system of interpunctuation marks gets more complicated. For instance, there are four different forms of vertically slanted double dashes that resemble "//" to mark the completion of the composition. Despite all the decorative signs that were available during the late period, the signs remained fairly simple in the inscriptions. One of the possible reasons may be that engraving is restricted while writing is not.

Baums identifies seven different punctuation marks needed for computer representation of Brahmi:

- single (𑁇) and double (𑁈) vertical bar (danda) – delimiting clauses and verses

- dot (𑁉), double dot (𑁊), and horizontal line (𑁋) – delimiting shorter textual units

- crescent (𑁌) and lotus (𑁍) – delimiting larger textual units

Evolution of the Brahmi script

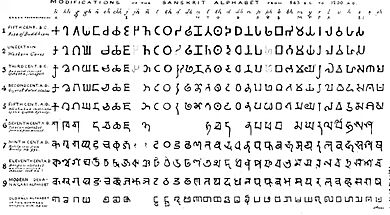

Brahmi is generally classified in three main types, which represent three main historical stages of its evolution over nearly a millennium:

- Early Brahmi represented in the Ashokan script. (3rd-1st century BCE)

- Middle Brahmi also known as "Kushana Brahmi" (1st-3rd centuries CE)

- Late Brahmi represented in the Gupta script (4th-6th centuries CE)

| Evolution of the Brahmi script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Ashoka | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Girnar | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kushan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gujarat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early Brahmi or "Ashokan Brahmi" (3rd–1st century BCE)

Early "Ashokan" Brahmi (3rd–1st century BCE) is regular and geometric, and organized in a very rational fashion:

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Mātrā | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑀅 | a /ɐ/ | 𑀓 | ka /kɐ/ | 𑀆 | ā /aː/ | 𑀓𑀸 | kā /kaː/ |

| 𑀇 | i /i/ | 𑀓𑀺 | ki /ki/ | 𑀈 | ī /iː/ | 𑀓𑀻 | kī /kiː/ |

| 𑀉 | u /u/ | 𑀓𑀼 | ku /ku/ | 𑀊 | ū /uː/ | 𑀓𑀽 | kū /kuː/ |

| 𑀏 | e /eː/ | 𑀓𑁂 | ke /keː/ | 𑀐 | ai /ɐi/ | 𑀓𑁃 | kai /kɐi/ |

| 𑀑 | o /oː/ | 𑀓𑁄 | ko /koː/ | 𑀒 | au /ɐu/ | 𑀓𑁅 | kau /kɐu/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | 𑀓 | ka /k/ | 𑀔 | kha /kʰ/ | 𑀕 | ga /ɡ/ | 𑀖 | gha /ɡʱ/ | 𑀗 | ṅa /ŋ/ | 𑀳 | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| Palatal | 𑀘 | ca /c/ | 𑀙 | cha /cʰ/ | 𑀚 | ja /ɟ/ | 𑀛 | jha /ɟʱ/ | 𑀜 | ña /ɲ/ | 𑀬 | ya /j/ | 𑀰 | śa /ɕ/ | ||

| Retroflex | 𑀝 | ṭa /ʈ/ | 𑀞 | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | 𑀟 | ḍa /ɖ/ | 𑀠 | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | 𑀡 | ṇa /ɳ/ | 𑀭 | ra /r/ | 𑀱 | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| Dental | 𑀢 | ta /t̪/ | 𑀣 | tha /t̪ʰ/ | 𑀤 | da /d̪/ | 𑀥 | dha /d̪ʱ/ | 𑀦 | na /n/ | 𑀮 | la /l/ | 𑀲 | sa /s/ | ||

| Labial | 𑀧 | pa /p/ | 𑀨 | pha /pʰ/ | 𑀩 | ba /b/ | 𑀪 | bha /bʱ/ | 𑀫 | ma /m/ | 𑀯 | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||

The final letter does not fit into the table above; it is 𑀴 ḷa.

Some famous inscriptions in the Early Brahmi script

The Brahmi script was the medium for some of the most famous inscriptions of ancient India, starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, c. 250 BCE.

Birthplace of the historical Buddha

In a particularly famous Edict, the Rummindei Edict in Lumbini, Nepal, Ashoka describes his visit in the 21st year of his reign, and designates Lumbini as the birthplace of the Buddha. He also, for the first time in historical records, uses the epithet "Sakyamuni" (Sage of the Shakyas), to describe the Buddha.

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

When King Devanampriya Priyadarsin had been anointed twenty years, he came himself and worshipped (this spot) because the Buddha Shakyamuni was born here. (He) both caused to be made a stone bearing a horse (?) and caused a stone pillar to be set up, (in order to show) that the Blessed One was born here. (He) made the village of Lummini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share (of the produce). — The Rummindei Edict, one of the Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka. |

𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀮𑀸𑀚𑀺𑀦𑀯𑀻𑀲𑀢𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀸𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀺𑀢𑁂𑀦 — Adapted from transliteration by E. Hultzsch |

Heliodorus Pillar inscription

The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India in Vidisha near modern Besnagar, by Heliodorus, an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas in Taxila to the court of the Shunga king Bhagabhadra. Historically, it is one of the earliest known inscriptions related to the Vaishnavism in India.

| Translation (English) |

Transliteration (original Brahmi script) |

Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced |

𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀲 𑀯𑀸(𑀲𑀼𑀤𑁂)𑀯𑀲 𑀕𑀭𑀼𑀟𑀥𑁆𑀯𑀚𑁄 𑀅𑀬𑀁 — Adapted from transliterations by E. J. Rapson, Sukthankar, Richard Salomon, and Shane Wallace. |

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" (1st–3rd centuries CE)

Middle Brahmi or "Kushana Brahmi" was in use from the 1st-3rd centuries CE. It is more rounded than its predecessor, and introduces some significant variations in shapes. Several characters (r̩ and l̩), classified as vowels, were added during the "Middle Brahmi" period between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE, in order to accommodate the transcription of Sanskrit:

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples

-

Inscribed Kushan statue of Western Satraps King Chastana, with inscription "Shastana" in Middle Brahmi script of the Kushan period (

Ṣa-sta-na).

Ṣa-sta-na).

Here, sta is the conjunct consonant of sa

is the conjunct consonant of sa  and ta

and ta  , vertically combined. Circa 100 CE.

, vertically combined. Circa 100 CE. -

The rulers of the Western Satraps were called Mahākhatapa ("Great Satrap") in their Brahmi script inscriptions, as here in a dedicatory inscription by Prime Minister Ayama in the name of his ruler Nahapana, Manmodi Caves, c. 100 CE.

Late Brahmi or "Gupta Brahmi" (4th–6th centuries CE)

Independent vowels

| Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| a /ə/ | ā /aː/ | ||

| i /i/ | ī /iː/ | ||

| u /u/ | ū /uː/ | ||

| e /eː/ | o /oː/ | ||

| ai /əi/ | au /əu/ | ||

| 𑀋 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | ka /k/ | kha /kʰ/ | ga /g/ | gha /ɡʱ/ | ṅa /ŋ/ | ha /ɦ/ | ||||||||||

| Palatal | ca /c/ | cha /cʰ/ | ja /ɟ/ | jha /ɟʱ/ | ña /ɲ/ | ya /j/ | śa /ɕ/ | |||||||||

| Retroflex | ṭa /ʈ/ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | ḍa /ɖ/ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | ṇa /ɳ/ | ra /r/ | ṣa /ʂ/ | |||||||||

| Dental | ta /t̪/ | tha /t̪ʰ/ | da /d̪/ | dha /d̪ʱ/ | na /n/ | la /l/ | sa /s/ | |||||||||

| Labial | pa /p/ | pha /pʰ/ | ba /b/ | bha /bʱ/ | ma /m/ | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||||||||

Examples

Descendants

Over the course of a millennium, Brahmi developed into numerous regional scripts. Over time, these regional scripts became associated with the local languages. A Northern Brahmi gave rise to the Gupta script during the Gupta Empire, sometimes also called "Late Brahmi" (used during the 5th century), which in turn diversified into a number of cursives during the Middle Ages, including the Siddhaṃ script (6th century) and Śāradā script (9th century).

Southern Brahmi gave rise to the Grantha alphabet (6th century), the Vatteluttu alphabet (8th century), and due to the contact of Hinduism with Southeast Asia during the early centuries CE, also gave rise to the Baybayin in the Philippines, the Javanese script in Indonesia, the Khmer alphabet in Cambodia, and the Old Mon script in Burma.

Also in the Brahmic family of scripts are several Central Asian scripts such as Tibetan, Tocharian (also called slanting Brahmi), and the one used to write the Saka language.

The Brahmi script also evolved into the Nagari script which in turn evolved into Devanagari and Nandinagari. Both were used to write Sanskrit, until the latter was merged into the former. The resulting script is widely adopted across India to write Sanskrit, Marathi, Hindi and its dialects, and Konkani.

The arrangement of Brahmi was adopted as the modern order of Japanese kana, though the letters themselves are unrelated.

| k- | kh- | g- | gh- | ṅ- | c- | ch- | j- | jh- | ñ- | ṭ- | ṭh- | ḍ- | ḍh- | ṇ- | t- | th- | d- | dh- | n- | p- | ph- | b- | bh- | m- | y- | r- | l- | v- | ś- | ṣ- | s- | h- | |

| Brahmi | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 |

| Gupta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Devanagari | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह |

Possible tangential relationships

Some authors have theorized that some of the basic letters of hangul may have been influenced by the 'Phags-pa script of the Mongol Empire, itself a derivative of the Tibetan alphabet, a Brahmi script (see Origin of Hangul). However, one of the authors, Gari Ledyard, on whose work much of this theorized connection rests, cautions against giving 'Phags-pa much credit in the development of Hangul:

I have devoted much space and discussion to the role of the Mongol ʼPhags-pa alphabet in the origin of the Korean alphabet, but it should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that role was quite limited. [...] The origin of the Korean alphabet is, in fact, not a simple matter at all. Those who say it is "based" in ʼPhags-pa are partly right; those who say it is "based" on abstract drawings of articulatory organs are partly right. ... Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: "According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol ʼPhags-pa script" ... ʼPhags-pa contributed none of the things that make this script perhaps the most remarkable in the world.

Unicode

Early Ashokan Brahmi was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Brahmi is U+11000–U+1107F. It lies within the Supplementary Multilingual Plane. As of June 2022 there are two non-commercially available fonts that support Brahmi, namely Noto Sans Brahmi commissioned by Google which covers almost all the characters, and Adinatha which only covers Tamil Brahmi. Segoe UI Historic, tied in with Windows 10, also features Brahmi glyphs.

The Sanskrit word for Brahmi, ब्राह्मी (IAST Brāhmī) in the Brahmi script should be rendered as follows: 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻.

| Brahmi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart: https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U11000.pdf (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1100x | 𑀀 | 𑀁 | 𑀂 | 𑀃 | 𑀄 | 𑀅 | 𑀆 | 𑀇 | 𑀈 | 𑀉 | 𑀊 | 𑀋 | 𑀌 | 𑀍 | 𑀎 | 𑀏 |

| U+1101x | 𑀐 | 𑀑 | 𑀒 | 𑀓 | 𑀔 | 𑀕 | 𑀖 | 𑀗 | 𑀘 | 𑀙 | 𑀚 | 𑀛 | 𑀜 | 𑀝 | 𑀞 | 𑀟 |

| U+1102x | 𑀠 | 𑀡 | 𑀢 | 𑀣 | 𑀤 | 𑀥 | 𑀦 | 𑀧 | 𑀨 | 𑀩 | 𑀪 | 𑀫 | 𑀬 | 𑀭 | 𑀮 | 𑀯 |

| U+1103x | 𑀰 | 𑀱 | 𑀲 | 𑀳 | 𑀴 | 𑀵 | 𑀶 | 𑀷 | 𑀸 | 𑀹 | 𑀺 | 𑀻 | 𑀼 | 𑀽 | 𑀾 | 𑀿 |

| U+1104x | 𑁀 | 𑁁 | 𑁂 | 𑁃 | 𑁄 | 𑁅 | 𑁆 | 𑁇 | 𑁈 | 𑁉 | 𑁊 | 𑁋 | 𑁌 | 𑁍 | ||

| U+1105x | 𑁒 | 𑁓 | 𑁔 | 𑁕 | 𑁖 | 𑁗 | 𑁘 | 𑁙 | 𑁚 | 𑁛 | 𑁜 | 𑁝 | 𑁞 | 𑁟 | ||

| U+1106x | 𑁠 | 𑁡 | 𑁢 | 𑁣 | 𑁤 | 𑁥 | 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 |

| U+1107x | 𑁰 | 𑁱 | 𑁲 | 𑁳 | 𑁴 | 𑁵 | BNJ | |||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Early Indian epigraphy

- Lipi

- Pre-Islamic scripts in Afghanistan

- Shankhalipi

- Tamil-Brahmi

- Anaikoddai seal