Yellow Peril facts for kids

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial colour-metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world.

The racist ideology of the Yellow Peril derives from a "core imagery of apes, lesser men, primitives, children, madmen, and beings who possessed special powers", which developed during the 19th century as Western imperialist expansion adduced East Asians as the Yellow Peril. In the late 19th century, the Russian sociologist Jacques Novikow coined the term in the essay "Le Péril Jaune" ("The Yellow Peril", 1897), which Kaiser Wilhelm II (r. 1888–1918) used to encourage the European empires to invade, conquer, and colonize China. To that end, using the Yellow Peril ideology, the Kaiser portrayed the Japanese and the Asian victory against the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) as an Asian racial threat to white Western Europe, and also exposes China and Japan as in alliance to conquer, subjugate, and enslave the Western world.

Contents

Origins

The racist and cultural stereotypes of the Yellow Peril originated in the late 19th century, when Chinese workers (people of different skin-color and physiognomy, language and culture) legally immigrated to Australia, Canada, the U.S., and New Zealand, where their work ethic inadvertently provoked a racist backlash against Chinese communities, for agreeing to work for lower wages than did the local white populations. In 1870, the French Orientalist and historian Ernest Renan warned Europeans of Eastern danger to the Western world; yet Renan had meant the Russian Empire (1721–1917), a country and nation whom the West perceived as more Asiatic than European.

Imperial Germany

Since 1870, the Yellow Peril ideology gave concrete form to the anti-East Asian racism of Europe and North America. In central Europe, the Orientalist and diplomat Max von Brandt advised Kaiser Wilhelm II that Imperial Germany had colonial interests to pursue in China. Hence, the Kaiser used the phrase die Gelbe Gefahr (The Yellow Peril) to specifically encourage Imperial German interests and justify European colonialism in China.

In 1895, Germany, France, and Russia staged the Triple Intervention to the Treaty of Shimonoseki (17 April 1895), which concluded the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), in order to compel Imperial Japan to surrender their Chinese colonies to the Europeans; that geopolitical gambit became an underlying casus belli of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). The Kaiser justified the Triple Intervention to the Japanese empire with racialist calls-to-arms against non-existent geopolitical dangers of the yellow race against the white race of Western Europe.

To justify European cultural hegemony, the Kaiser used the allegorical lithograph Peoples of Europe, Guard Your Most Sacred Possessions (1895), by Hermann Knackfuss, to communicate his geopolitics to other European monarchs. The lithograph depicts Germany as the leader of Europe, personified as a "prehistoric warrior-goddesses being led by the Archangel Michael against the 'yellow peril' from the East", which is represented by "dark cloud of smoke [upon] which rests an eerily calm Buddha, wreathed in flame". Politically, the Knackfuss lithograph allowed Kaiser Wilhelm II to believe he prophesied the imminent race war that would decide global hegemony in the 20th century.

Imperial Russia

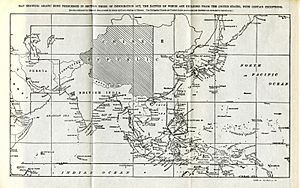

In the late 19th century, with the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881), the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) China recovered the eastern portion of the Ili River basin (Zhetysu), which Russia had occupied for a decade, since the Dungan Revolt (1862–77). In that time, the mass communications media of the West misrepresented China as an ascendant military power, and applied Yellow Peril ideology to evoke racist fears that China would conquer Western colonies, such as Australia.

Imperial Russian writers, notably Symbolists, expressed fears of a "second Tatar yoke" or a "Mongolian wave" following the lines of "Yellow Peril". Vladimir Solovyov combined Japan and China into supposed "Pan-Mongolians" who would conquer Russia and Europe. A similar idea and fear was expressed by Dmitry Merezhkovskii in Zheltolitsye pozitivisty ("Yellow-Faced Positivists") in 1895 and Griadushchii Kham ("The Coming Boor") in 1906.

The works of explorer Vladimir K. Arsenev also illustrated the ideology of Yellow Peril in Tsarist Russia. The fear continued into the Soviet era where it contributed to the Soviet internal deportation of Koreans. In a 1928 report to the Dalkrai Bureau, Arsenev stated "Our colonisation is a type of weak wedge on the edge of the primordial land of the yellow peoples." In the earlier 1914 monograph The Chinese in the Ussuri Region, Arsenev characterised people of three East Asian nationalities (Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese) as a singular 'yellow peril', criticising immigration to Russia and presenting the Ussuri region as a buffer against "onslaught".

Canada

The Chinese head tax was a fixed fee charged to each Chinese person entering Canada. The head tax was first levied after the Canadian parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 and was meant to discourage Chinese people from entering Canada after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The tax was abolished by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which outright prevented all Chinese immigration except for that of business people, clergy, educators, students, and some others.

United States

In 1854, as editor of the New-York Tribune, Horace Greeley published "Chinese Immigration to California" an editorial opinion supporting the popular demand for the exclusion of Chinese workers and people from California. Without using the term "yellow peril," Greeley compared the arriving coolies to the African slaves who survived the Middle Passage.

In 1870s California, despite the Burlingame Treaty (1868) allowing legal migration of unskilled laborers from China, the native white working-class demanded that the U.S. government cease the immigration of Chinese people who took jobs from native-born white-Americans, especially during an economic depression.

In Los Angeles, Yellow Peril racism provoked the Chinese Massacre of 1871. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, the leader of the Workingmen's Party of California, the demagogue Denis Kearney, successfully applied Yellow Peril ideology to his politics against the press, capitalists, politicians, and Chinese workers, and concluded his speeches with the epilogue: "and whatever happens, the Chinese must go!" As in the case of Irish-Catholic immigrants, the popular press misrepresented Asian peoples as culturally subversive, whose way of life would diminish republicanism in the U.S.; hence, racist political pressure compelled the U.S. government to legislate the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which remained the effective immigration-law until 1943. Moreover, following the example of Kaiser Wilhelm II's use of the term in 1895, the popular press in the U.S. adopted the phrase "yellow peril" to identify Japan as a military threat, and to describe the many emigrants from Asia.

Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, the anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion (August 1899 – September 1901) reinforced the racist stereotypes of East Asians as a Yellow Peril to white people. The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (called the Boxers in the West) was an anti-colonial martial-arts organization who blamed the problems of China on the presence of Western colonies in China proper. The Boxers sought to save China by killing Westerners in China and Chinese Christian or Westernized people. In the early summer of 1900, Prince Zaiyi allowed the Boxers into Beijing to kill Westerners and Chinese Christians in siege to the foreign legations. Afterwards, Ronglu, Qing Commander-in-Chief and Yikuang (Prince Qing), resisted and expelled the Boxers from Beijing after days of fighting.

Western perception

Most of the victims of the Boxer Rebellion were Chinese Christians, but the massacres of Chinese people were of no interest to the Western world, which demanded Asian blood to avenge the Westerners in China killed by the Boxers. In response, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Imperial Japan, Imperial France, Imperial Russia, and Imperial Germany, Austria–Hungary and Italy formed the Eight-Nation Alliance and dispatched an international military expeditionary force to end the Siege of the International Legations in Beijing.

The Russian press presented the Boxer Rebellion in racialist and religious terms as a cultural war between White Holy Russia and Yellow Pagan China. The press further supported the Yellow Peril apocalypse with quotations from the Sinophobic poems of the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov. Likewise, in the press, the aristocracy demanded action against the Asian threat. Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy urged Imperial Russia and other European monarchies to jointly partition China and to end the Yellow Peril to Christendom. Hence, on 3 July 1900, in response to the Boxer Rebellion, Russia expelled the Chinese community (5,000 people) from Blagoveshchensk. From 4 to 8 July, the Tsarist police, Cossack cavalry, and local vigilantes killed thousands of Chinese people at the Amur River.

In the Western world, news of Boxer atrocities against Westerners in China provoked Yellow Peril racism in Europe and North America, where the Chinese' rebellion was perceived as a race war between the yellow race and the white race. In that vein, The Economist magazine warned in 1905:

The history of the Boxer movement contains abundant warnings, as to the necessity of an attitude of constant vigilance, on the part of the European Powers, when there are any symptoms that a wave of nationalism is about to sweep over the Celestial Empire.

Sixty-one years later, in 1967, during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Red Guard attacked the British embassy shouting “Kill!, Kill!, Kill!”. A diplomat remarked that the Boxers had used the same chant.

Colonial vengeance

On 27 July 1900, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave the racist Hunnenrede (Hun speech) exhorting his soldiers to barbarism and that Imperial German soldiers depart Europe for China and suppress the Boxer Rebellion by acting like "Huns" and committing atrocities against the Chinese (Boxer and civilian):

When you come before the enemy, you must defeat him, a pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands will fall to your sword! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns, under their King Attila, made a name for themselves with their ferocity, which tradition still recalls; so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinaman will ever dare look a German in the eye, even with a squint!

Fearful of harm to the public image of Imperial Germany, the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) published a redacted version of the Hun Speech that was expurgated of the exhortation to racist barbarism. Annoyed by Foreign Office censorship, the Kaiser published the unexpurgated Hun Speech, which "evoked images of a Crusade and considered the current crisis [the Boxer Rebellion] to amount to a war between Occident and Orient." However, that "elaborate accompanying music, and the new ideology of the Yellow Peril stood in no relation to the actual possibilities and results" of geopolitical policy based upon racist misperception.

Exhortation to barbarism

The Kaiser ordered the expedition-commander, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, to behave barbarously. In that time, the Kaiser's best friend, Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, wrote to another friend that the Kaiser wanted to raze Beijing and kill the populace to avenge the murder of Baron Clemens von Ketteler, Imperial Germany's minister to China. Only the Eight-Nation Alliance's refusal of barbarism to resolve the siege of the legations saved the Chinese populace of Beijing from the massacre recommended by Imperial Germany. In August 1900, an international military force of Russian, Japanese, British, French, and American soldiers captured Beijing before the German force had arrived at the city.

Praxis of barbarism

The eight-nation alliance sacked Beijing in vengeance for the Boxer Rebellion; the magnitude of pillaging and burning indicated "a sense that the Chinese were less than human" to the Western powers.

The American missionary Luella Miner reported that "the conduct of the Russian soldiers is atrocious, the French are not much better, and the Japanese are looting and burning without mercy."

From contemporary Western observers, German, Russian, and Japanese troops received the greatest criticism for their ruthlessness and willingness to want execute Chinese of all ages and backgrounds, sometimes by burning the entire villages. The Americans and British paid General Yuan Shikai and his army (the Right Division) to help the Eight Nation Alliance suppress the Boxers.

The expedition of German Field Marshal Waldersee arrived in China on 27 September 1900, after the military defeat of the Boxer Rebellion by the Eight Nation Alliance, yet he launched 75 punitive raids into northern China to search for and destroy the remaining Boxers. The German soldiers killed more peasants than Boxer guerrillas because by autumn 1900, the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (the Boxers) had posed no threat. On 19 November 1900, at the Reichstag, the German Social Democrat politician August Bebel criticised the Kaiser's attack upon China as shameful to Germany:

No, this is no crusade, no holy war; it is a very ordinary war of conquest ... A campaign of revenge as barbaric as has never been seen in the last centuries, and not often at all in History ... not even with the Huns, not even with the Vandals ... That is not a match for what the German and other troops of foreign powers, together with the Japanese troops, have done in China.

Cultural fear

The political praxis of Yellow Peril racism calls for apolitical racial unity among the White peoples of the world. To resolve a contemporary problem (economic, social, political) the racialist politician calls for White unity against the non-white Other who threatens Western civilization from distant Asia. Despite the Western powers' military defeat of the anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion, Yellow Peril fear of Chinese nationalism became a cultural factor among white people: That "the Chinese race" mean to invade, vanquish, and subjugate Christian civilization in the Western world.

Racial annihilation

The Darwinian threat

The Yellow Peril racialism of the Austrian philosopher Christian von Ehrenfels proposed that the Western world and the Eastern world were in a Darwinian racial struggle for domination of the planet, which the yellow race was winning. That the Chinese were an inferior race of people whose Oriental culture lacked "all potentialities ... determination, initiative, productivity, invention, and organizational talent" supposedly innate to the white cultures of the West.

The gist of von Ehrenfels's nihilistic racism was that Asian conquest of the West equaled white racial-annihilation; Continental Europe subjugated by a genetically superior Sino–Japanese army consequent to a race war that the Western world would fail to thwart or win.

Race war

To end the threat of the Yellow Peril to the Western world, von Ehrenfels proposed White racial unity among the nations of the West, in order to jointly prosecute a preemptive war of ethnic conflicts to conquer Asia, before it became militarily infeasible. Then establish a worldwide racial hierarchy organized as an hereditary caste system, headed by the White race in each conquered country of Asia. That an oligarchy of the Aryan White people would form, populate, and lead the racial castes of the ruling class, the military forces, and the intelligentsia; and that in each conquered country, the Yellow and the Black races would be slaves, the economic base of the worldwide racial hierarchy.

Xenophobia

Germany and Russia

From 1895, Kaiser Wilhelm used Yellow Peril ideology to portray Imperial Germany as defender of the West against conquest from the East. In pursuing Weltpolitik policies meant to establish Germany as the dominant empire, the Kaiser manipulated his own government officials, public opinion, and other monarchs. In a letter to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, the Kaiser said: "It is clearly the great task of the future for Russia to cultivate the Asian continent, and defend Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race". In The Bloody White Baron (2009), the historian James Palmer explains the 19th-century socio-cultural background from which Yellow Peril ideology originated and flourished:

{{blockquote|The 1890s had spawned in the West the specter of the "Yellow Peril", the rise to world dominance of the Asian peoples. The evidence cited was Asian population growth, immigration to the West (America and Australia in particular), and increased Chinese settlement along the Russian border. These demographic and political fears were accompanied by a vague and ominous dread of the mysterious powers supposedly possessed by the initiates of Eastern religions. There is a striking German picture of the 1890s, depicting the dream that inspired Kaiser Wilhelm II to coin the term "Yellow Peril", that shows the union of these ideas. It depicts the nations of Europe, personified as heroic, but vulnerable, female figures guarded by the Archangel Michael, gazing apprehensively towards a dark cloud of smoke in the East, in which rests an eerily calm Buddha, wreathed in flame ...

As his cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm knew that Tsar Nicholas shared his anti-Asian racism and believed he could persuade the Tsar to abrogate the Franco-Russian Alliance (1894) and then to form a German–Russian alliance against Britain. In manipulative pursuit of Imperial German Weltpolitik "Wilhelm II's deliberate use of the 'yellow peril' slogan was more than a personal idiosyncrasy, and fitted into the general pattern of German foreign policy under his reign, i.e. to encourage Russia's Far Eastern adventures, and later to sow discord, between the United States and Japan.

United States

19th century

In the U.S., Yellow Peril xenophobia was legalized with the Page Act of 1875, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the Geary Act of 1892. The Chinese Exclusion Act replaced the Burlingame Treaty (1868), which had encouraged Chinese migration, and provided that "citizens of the United States in China, of every religious persuasion, and Chinese subjects, in the United States, shall enjoy entire liberty of conscience, and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution, on account of their religious faith or worship, in either country", withholding only the right of naturalized citizenship.

In the Western U.S., the frequency with which racists executed Chinese people originated the phrase, "Having a Chinaman's chance in Hell", meaning "no chance at all" of surviving a false accusation. In Tombstone, Arizona, sheriff Johnny Behan and mayor John Clum organized the "Anti-Chinese League" in 1880, which was reorganized into the "Anti-Chinese Secret Society of Cochise County" in 1886. In 1880, the Yellow Peril pogrom of Denver featured the destruction of the local Chinatown ghetto. In 1885, the Rock Springs massacre destroyed a Wyoming Chinese community. In Washington Territory, Yellow Peril fear provoked the Attack on Squak Valley Chinese laborers, 1885; the arson of the Seattle Chinatown; and the Tacoma riot of 1885, by which the local white inhabitants expelled the Chinese community from their towns. In Seattle, the Knights of Labor expelled 200 Chinese people with the Seattle riot of 1886. In Oregon, 34 Chinese gold miners were killed in the Hells Canyon Massacre (1887).

20th century

Under nativist political pressure, the Immigration Act of 1917 established an Asian Barred Zone of countries from which immigration to the U.S. was forbidden. The Cable Act of 1922 (Married Women's Independent Nationality Act) guaranteed citizenship to independent women unless they were married to a nonwhite alien ineligible for naturalization. Asian men and women were excluded from American citizenship.

In practice, the Cable Act of 1922 reversed some racial exclusions, and granted independent women citizenship exclusively to women married to white men. Analogously, the Cable Act allowed the government to revoke the citizenship of an American white woman married an Asian man. The law was formally challenged before the Supreme Court, with the case of Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922), whereby a Japanese–American man tried to demonstrate that the Japanese people are a white race eligible for naturalized American citizenship. The Court ruled that the Japanese are not white people; two years later, the National Origins Quota of 1924 specifically excluded the Japanese from entering the US and from American citizenship.

Ethnic national character

To "preserve the ideal of American homogeneity", the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 (numeric limits) and the Immigration Act of 1924 (fewer southern and eastern Europeans) restricted admission to the United States according to the skin color and the race of the immigrant. In practice, the Emergency Quota Act used outdated census data to determine the number of colored immigrants admitted to the U.S. To protect WASP ethnic supremacy (social, economic, political) in the 20th century, the Immigration Act of 1924 used the twenty-year-old census of 1890, because its 19th-century demographic-group percentages favored more admissions of WASP immigrants from western and northern Europe, and fewer admissions of colored immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe.

To ensure that the immigration of colored peoples did not change the WASP national character of the United States, the National Origins Formula (1921–1965) meant to maintain the status quo percentages of "ethnic populations" in lesser proportion to the existing white populations; thus, the yearly quota allowed only 150,000 People of Color into the U.S.A. In the event, the national-origins Formula was voided and repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Socially acceptable Asian

In the 1930s, Yellow Peril stereotypes were common to US culture, exemplified by the cinematic versions of the Asian detectives Charlie Chan (Warner Oland) and Mr. Moto (Peter Lorre), originally literary detectives in novels and comic strips. White actors portrayed the Asian men and made the fictional characters socially acceptable in mainstream American cinema, especially when the villains were secret agents of Imperial Japan.

American proponents of the Japanese Yellow Peril were the military-industrial interests of the China Lobby (right-wing intellectuals, businessmen, Christian missionaries) who advocated financing and supporting the warlord Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, a Methodist convert whom they represented as the Christian Chinese savior of China, then embroiled in the Chinese Civil War (1927–1937, 1946–1950). After the Japanese invaded China in 1937, the China Lobby successfully pressured the U.S. government to aid Chiang Kai-shek's faction. The news media's reportage (print, radio, cinema) of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) favored China, which politically facilitated the American financing and equipping of the anticommunist Kuomintang, the Chiang Kai-shek faction in the civil war against the Communist faction led by Mao Tse-tung.

Pragmatic racialism

In 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Roosevelt administration formally declared China an ally of the U.S., and the news media modified their use of Yellow Peril ideology to include China to the West, criticizing contemporary anti-Chinese laws as counterproductive to the war effort against Imperial Japan. The wartime zeitgeist and the geopolitics of the U.S. government presumed that defeat of the Imperial Japan would be followed by postwar China developing into a capitalist economy under the strongman leadership of the Christian Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party).

In his relations with the American government and his China Lobby sponsors, Chiang requested the repeal of American anti-Chinese laws; to achieve the repeals, Chiang threatened to exclude the American business community from the "China Market", the economic fantasy that the China Lobby promised to the American business community. In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed, but, because the National Origins Act of 1924 was contemporary law, the repeal was a symbolic gesture of American solidarity with the people of China.

21st century

The American academic Frank H. Wu said that anti-Chinese sentiment incited by people such as Steve Bannon and Peter Thiel is recycling anti-Asian hatred from the 19th century into a "new Yellow Peril" that is common to White populist politics that do not distinguish between Asian foreigners and Asian-American U.S. citizens. That American cultural anxiety about the geopolitical ascent of the People's Republic of China originates in the fact that, for the first time in centuries, the Western world, led by the U.S., is challenged by a people whom Westerners viewed as culturally backward and racially inferior only a generation earlier. That the U.S. perceives China as "the enemy", because their economic success voids the myth of white supremacy upon which the West claims cultural superiority over the East. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated and increased the occurrence of xenophobia and anti-Chinese racism, which the academic Chantal Chung said has "deep roots in yellow peril ideology".

Australia

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, fear of the Yellow Peril was a cultural feature of the white peoples who sought to establish a country and a society in the Australian continent. The racialist fear of the nonwhite Asian Other was a thematic preoccupation common to invasion literature novels, such as The Yellow Wave: A Romance of the Asiatic Invasion of Australia (1895), The Colored Conquest (1904), The Awakening to China (1909), and the Fools' Harvest (1939). Such fantasy literature featured an Asian invasion of "the empty north" of Australia, which was populated by the Aboriginal Australians, the nonwhite, native Other with whom the white emigrants competed for living space. In the novel White or Yellow?: A Story of the Race War of A.D. 1908 (1887), the journalist and labor leader William Lane said that a horde of Chinese people legally arrived to Australia and overran white society and monopolized the industries for exploiting the natural resources of the Australian "empty north".

Racial equality thwarted

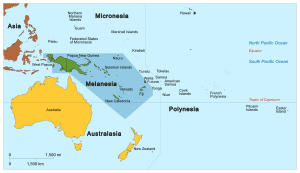

In 1901, the Australian federal government adopted the White Australia policy that had been informally initiated with the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which generally excluded Asians, but in particular excluded the Chinese and the Melanesian peoples. Historian C. E. W. Bean said that the White Australia policy was "a vehement effort to maintain a high, Western standard of economy, society, and culture (necessitating, at that stage, however it might be camouflaged, the rigid exclusion of Oriental peoples)" from Australia. In 1913, appealing to the irrational fear of the Yellow Peril, the film Australia Calls (1913) depicted a "Mongolian" invasion of Australia, which eventually is defeated by ordinary Australians with underground, political resistance and guerrilla warfare, and not by the army of the Australian federal government.

In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference (28 June 1919), supported by Britain and the U.S., Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes vehemently opposed Imperial Japan's request for the inclusion of the Racial Equality Proposal to Article 21 of the Covenant of the League of Nations (13 February 1919):

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord, as soon as possible, to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

Aware that the British delegation opposed the racial equality clause in Article 21 of the Covenant, conference chairman U.S. President Woodrow Wilson acted to prevent de jure racial equality among the nations of the world, with his unilateral requirement of a unanimous vote by the countries in the League of Nations. On 11 April 1919, most countries in the conference voted to include the Racial Equality Proposal to Article 21 of the Covenant of the League of Nations; only the British and American delegations opposed the racial equality clause. Moreover, to maintain the White Australia policy, the Australian government sided with Britain and voted against Japan's formal request that the Racial Equality Proposal be included to Article 21 of the covenant of the League of Nations; that defeat in international relations greatly influenced Imperial Japan to militarily confront the Western world.

France

Colonial empire

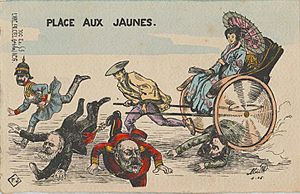

In the late 19th century, French imperialist politicians invoked the Péril jaune (Yellow Peril) in their negative comparisons of France's low birth-rate and the high birth-rates of Asian countries. From that racist claim arose an artificial, cultural fear among the French population that immigrant-worker Asians soon would "flood" France, which could be successfully countered only by increased fecundity of French women. Then, France would possess enough soldiers to thwart the eventual flood of immigrants from Asia. From that racialist perspective, the French press sided with Imperial Russia during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), by representing the Russians as heroes defending the white race against the Japanese Yellow Peril.

In the early 20th century, in 1904, the French journalist René Pinon reported that the Yellow Peril were a cultural, geopolitical, and existential threat to white civilization in the Western world:

The "Yellow Peril" has entered already into the imagination of the people, just as represented in the famous drawing [Peoples of Europe, Guard Your Most Sacred Possessions,1895] of the Emperor Wilhelm II: In a setting of conflagration and bloodshed, Japanese and Chinese hordes spread out over all Europe, crushing under their feet the ruins of our capital cities and destroying our civilizations, grown anemic due to the enjoyment of luxuries, and corrupted by the vanity of spirit.

Hence, little by little, there emerges the idea that even if a day must come (and that day does not seem near) the European peoples will cease to be their own enemies and even economic rivals, there will be a struggle ahead to face and there will rise a new peril, the yellow man.

The civilized world has always organized itself before and against a common adversary: for the Roman world, it was the barbarian; for the Christian world, it was Islam; for the world of tomorrow, it may well be the yellow man. And so we have the reappearance of this necessary concept, without which peoples do not know themselves, just as the "Me" only takes conscience of itself in opposition to the "non-Me": The Enemy.

Despite the claimed Christian idealism of the civilizing mission, from the start of colonization in 1858, the French exploited the natural resources of Vietnam as inexhaustible and the Vietnamese people as beasts of burden. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the First Indochina War (1946–1954) justified recolonization of Vietnam as a defense of the white West against the péril jaune — specifically that the Communist Party of Vietnam were puppets of the People's Republic of China, which is part of the "international communist conspiracy" to conquer the world. Therefore, French anticommunism utilized orientalism to dehumanize the Vietnamese into "the nonwhite Other"; which yellow-peril racism allowed atrocities against Viet Minh prisoners of war during la sale guerre ("dirty war"). In that time, yellow-peril racism remained one of the ideological bases for the existence of French Indochina, thus the French news media's racialist misrepresentations of Viet Minh guerrillas being part of the innombrables masses jaunes (innumerable yellow hordes); being one of many vagues hurlantes (roaring waves) of masses fanatisées (fanatical hordes).

Contemporary France

In Behind the Bamboo Hedge: The Impact of Homeland Politics in the Parisian Vietnamese Community (1991) Gisèle Luce Bousquet said that the péril jaune, which traditionally colored French perceptions of Asians, especially of Vietnamese people, remains a cultural prejudice of contemporary France; hence the French perceive and resent the Vietnamese people of France as academic overachievers who take jobs from "native French" people.

In 2015, the cover of the January issue of Fluide Glacial magazine featured a cartoon, Yellow Peril: Is it Already Too Late?, which depicts a Chinese-occupied Paris where a sad Frenchman is pulling a rickshaw, transporting a Chinese man, in 19th c. French colonial uniform, accompanied by a barely dressed, blonde French woman. The editor of Fluide Glacial, Yan Lindingre, defended the magazine cover and the subject as satire and mockery of French fears of China's economic threat to France. In an editorial addressing the Chinese government's complaint, Lindingre said, "I have just ordered an extra billion copies printed, and will send them to you via chartered flight. This will help us balance our trade deficit, and give you a good laugh".

Italy

In the 20th century, from their perspective, as nonwhite nations in a world order dominated by the white nations, the geopolitics of Ethiopia–Japan relations allowed Imperial Japan and Ethiopia to avoid imperialist European colonization of their countries and nations. Before the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1934–1936), Imperial Japan had given diplomatic and military support to Ethiopia against invasion by Fascist Italy, which implied military assistance. In response to that Asian anti-imperialism, Benito Mussolini ordered a Yellow Peril propaganda campaign by the Italian press, which represented Imperial Japan as the military, cultural, and existential threat to the Western world, by way of the dangerous "yellow race–black race" alliance meant to unite Asians and Africans against the white people of the world.

In 1935, Mussolini warned of the Japanese Yellow Peril, specifically the racial threat of Asia and Africa uniting against Europe. In the summer of 1935, the National Fascist Party (1922–43) often staged anti–Japanese political protests throughout Italy. Nonetheless, as right-wing imperial powers, Japan and Italy pragmatically agreed to disagree; in exchange for Italian diplomatic recognition of Manchukuo (1932–45), the Japanese puppet state in China, Imperial Japan would not aid Ethiopia against Italian invasion and so Italy would end the anti–Japanese Yellow Peril propaganda in the national press of Italy.

Mexico

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), Chinese-Mexicans were subjected to racist abuse, like before the revolt, for not being Christians, specifically Roman Catholic, for not being racially Mexican, and for not soldiering and fighting in the Revolution against the thirty-five-year dictatorship (1876–1911) of General Porfirio Díaz.

The notable atrocity against Asian people was the three-day Torreón massacre (13–15 May 1911) in northern Mexico, wherein the military forces of Francisco I. Madero killed 308 Asian people (303 Chinese, 5 Japanese), because they were deemed a cultural threat to the Mexican way of life. In 1913, after the Constitutional Army captured the city of Tamasopo, San Luis Potosí state, the soldiers and the town-folk expelled the Chinese community by sacking and burning the Chinatown.

During and after the Mexican Revolution, the Roman Catholic prejudices of Yellow Peril ideology facilitated racial discrimination and violence against Chinese Mexicans, usually for "stealing jobs" from native Mexicans. Anti–Chinese nativist propaganda misrepresented the Chinese people as unhygienic, prone to immorality and spreading diseases that would biologically corrupt and degenerate La Raza (the Mexican race) and generally undermining the Mexican patriarchy.

In the 1930s, approximately 70 per cent of the Chinese and the Chinese–Mexican population was expelled from the Mexican United States by the bureaucratic ethnic culling of the Mexican population.

Turkey

In 1908, at the end of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922) the Young Turk Revolution ascended the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) to power, which the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état reinforced with the Raid on the Sublime Porte. In admiration and emulation that the modernization of Japan during the Meiji Restoration (1868) was realised without the Japanese people losing their national identity, the CUP intended to modernize Turkey into the "Japan of the Near East". To that end, the CUP considered allying Turkey with Japan in a geopolitical effort to unite the peoples of the Eastern world to fight a racial war of extermination against the White colonial empires of the West. Politically, the cultural, nationalist, and geopolitical affinities of Turkey and Japan were possible because, in Turkish culture, the "yellow" color of "Eastern gold" symbolizes the innate moral superiority of the East over the West.

Fear of the Yellow Peril occurs against the Chinese communities of Turkey, usually as political retaliation against the PRC government's repressions and human-rights abuses against the Muslim Uighur people in the Xinjiang province of China.

South Africa

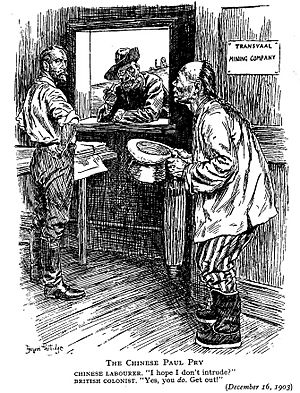

In 1904, after the conclusion of the Second Boer War, the Unionist Government of the Britain authorized the immigration to South Africa of approximately 63,000 Chinese laborers to work the gold mines in the Witwatersrand basin.

On 26 March 1904, approximately 80,000 people attended a social protest against the use of Chinese laborers in the Transvaal held in Hyde Park, London, to publicize the exploitation of Chinese South Africans. The Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress then passed a resolution declaring:

That this meeting, consisting of all classes of citizens of London, emphatically protests against the action of the Government in granting permission to import into South Africa indentured Chinese labor under conditions of slavery, and calls upon them to protect this new colony from the greed of capitalists and the Empire from degradation.

The mass immigration of indentured Chinese laborers to mine South African gold for wages lower than acceptable to the native white men, contributed to the 1906 electoral loss of the financially conservative British Unionist government that then governed South Africa.

After 1910, most Chinese miners were repatriated to China because of the great opposition to them, as "colored people" in white South Africa, analogous to anti-Chinese laws in the US during the early 20th century. In the event, despite the racial violence between white South African miners and Chinese miners, the Unionist government achieved the economic recovery of South Africa after the Second Boer War by rendering the gold mines of the Witwatersrand Basin the most productive in the world.

New Zealand

In the late 19th and the early 20th centuries, populist Prime Minister Richard Seddon compared the Chinese people to monkeys, and so used the Yellow Peril to promote racialist politics in New Zealand. In 1879, in his first political speech, Seddon said that New Zealand did not wish her shores "deluged with Asiatic Tartars. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'".

Moreover, in 1905, in the city of Wellington, the white supremacist Lionel Terry murdered Joe Kum Yung, an old Chinese man, in protest against Asian immigration to New Zealand. Laws promulgated to limit Chinese immigration included a heavy poll tax, introduced in 1881 and lowered in 1937, after Imperial Japan's invasion and occupation of China. In 1944, the poll tax was abolished, and the New Zealand government formally apologized to the Chinese populace of New Zealand.

Literary Yellow Peril

Novels

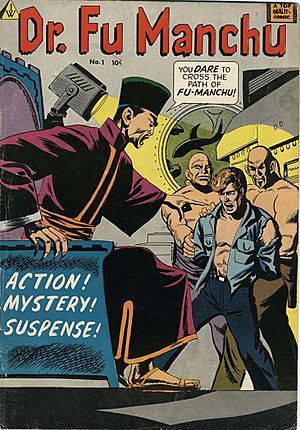

The Yellow Peril was a common subject for 19th-century adventure fiction, of which Dr. Fu Manchu is the representative villain, created in the likeness of the villain in the novel The Yellow Danger; Or, what Might Happen in the Division of the Chinese Empire Should Estrange all European Countries (1898), by M. P. Shiel. The Chinese gangster Fu Manchu is a mad scientist intent upon conquering the world, but is continually foiled by the British policeman Sir Denis Nayland Smith and his companion Dr. Petrie, in thirteen novels (1913–59), by Sax Rohmer.

Yellow Peril: The Adventures of Sir John Weymouth–Smythe (1978), by Richard Jaccoma, is a pastiche of the Fu Manchu novels.

The Yellow Peril (1989), by Bao Mi (Wang Lixiong) presents a civil war in the People's Republic of China that escalates to internal nuclear warfare, which then escalates into the Third World War. Published after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, the political narrative of Yellow Peril presents the dissident politics of anti–Communist Chinese, and consequently was suppressed by the Chinese government.

Short stories

- The Infernal War (La Guerre infernale, 1908), by Pierre Giffard, illustrated by Albert Robida, is a science fiction story that depicts the Second World War as a fight among the empires of the White man, which distraction allows China to invade Russia, and Japan to invade the U.S.

- In "Under the Ban of Li Shoon" (1916) and "Li Shoon's Deadliest Mission" (1916), H. Irving Hancock introduced the villain Li Shoon, a "tall and stout" man with "a round, moon-like yellow face" with "bulging eyebrows" above "sunken eyes". Personally, Li Shoon is "an amazing compound of evil" and intellect, which makes him "a wonder at everything wicked" and "a marvel of satanic cunning."

- The Peril of the Pacific (1916), by J. Allan Dunn, describes a fantastical, 1920 Japanese invasion of the U.S. mainland realized by an alliance between treasonous Japanese-Americans and the Imperial Japanese Navy. The racist language of J. Allan Dunn's narrative communicates the irrational, Yellow Peril fear of and about Japanese-American citizens in California, who were exempt from arbitrary deportation by the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907.

- "The Unparalleled Invasion" (1910), by Jack London, set between 1976 and 1987, shows China conquering and colonizing neighboring countries. In self-defense, the Western World retaliate with biological warfare. Western armies and navies kill the Chinese refugees at the border, and punitive expeditions kill the survivors in China. London describes this war of extermination as necessary to the white settler colonialism of China, in accordance with "the democratic American program".

- In "He" (1926), by H. P. Lovecraft, the protagonist white-man is allowed to see the future of planet Earth, and sees "yellow men" triumphantly dancing among the ruins of the White man's world. In "The Horror at Red Hook" (1927), features Red Hook, New York, as a place were "slant-eyed immigrants practice nameless rites in honor of heathen gods by the light of the moon."

Cinematic Yellow Peril

In the 1930s, American cinema (Hollywood) presented contradictory images of East Asian men: (i) The malevolent master-criminal, Dr. Fu Manchu; and (ii) The benevolent master-detective, Charlie Chan. Fu Manchu is "[Sax] Rohmer's concoction of cunning Asian villainy [that] connects with the irrational fears of proliferation and incursion: Racist myths often carried by the water imagery of flood, deluge, the tidal waves of immigrants, rivers of blood."

In 1936, when the Nazis banned the novels of Sax Rohmer in Germany, because they believed him Jewish, Rohmer denied being racist and published a letter declaring himself "a good Irishman", yet was disingenuous about the why of the Nazi book-ban, because "my stories are not inimical to Nazi ideals." In science fiction cinema, the "futuristic Yellow Peril" is embodied by Emperor Ming the Merciless is an iteration of the Fu Manchu trope who is the nemesis of the Flash Gordon; likewise, Buck Rogers fights against the Mongol Reds, a Yellow Peril who conquered the U.S. in the 25th century.

Comic books

In 1937, the publisher DC Comics featured "Ching Lung" on the cover and in the first issue of Detective Comics (March 1937). Years later, the character would be revisited in New Super-Man (June 2017), where his true identity is revealed to be All-Yang, the villainous twin brother of I-Ching, who deliberately cultivated the Yellow Peril image of Ching Lung to show Super-Man how the West caricaturized and vilified the Chinese.

In the late 1950s, Atlas Comics (Marvel Comics) published Yellow Claw, a pastiche of the Fu Manchu stories. Unusually for the time, the racist imagery was counterbalanced by the Asian-American FBI agent, Jimmy Woo, as his principal opponent.

In 1964, Stan Lee and Don Heck introduced, in Tales of Suspense, the Mandarin, a Yellow Peril-inspired supervillain and archenemy of Marvel Comics superhero Iron Man. In Iron Man 3 (2013), set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Mandarin appears as the leader of the Ten Rings terrorist organization. Hero Tony Stark (played by Robert Downey, Jr.) discovers that the Mandarin is an English actor, Trevor Slattery (Ben Kingsley), who was hired by Aldrich Killian (Guy Pearce) as a cover for his own criminal activities. According to director Shane Black and screenwriter Drew Pearce, making the Mandarin an impostor avoided Yellow Peril stereotyping while modernizing it with a message about the use of fear by the military industrial complex.

In the 1970s, DC Comics introduced a clear Fu Manchu analogue in supervillain Ra's al Ghul, created by Dennis O'Neil, Neal Adams and Julius Schwartz. While maintaining a level of racial ambiguity, the character's signature Fu Manchu beard and "Chinaman" clothing made him an instance of Yellow Peril stereotyping. When adapting the character for Batman Begins, screenwriter David Koepp and director Christopher Nolan had Ken Watanabe play an imposter Ra's al Ghul to distract from his true persona, played by Liam Neeson. As with Iron Man 3, this was this done to avoid the problematic origins of the character, making them a deliberate fake rather than a true portrayal of a different culture's insidious designs.

Marvel Comics used Fu Manchu as the principal foe of his son, Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu. As the result of Marvel Comics later losing the rights to the Fu Manchu name, his later appearances give him the real name of Zheng Zu. The Marvel Cinematic Universe film Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021) replaces Fu Manchu with Xu Wenwu (Tony Leung), an original character partially inspired by Zheng Zu and the Mandarin; thus downplaying yellow peril implications as Wenwu is opposed by an Asian superhero, his son Shang-Chi (Simu Liu), rather than Tony Stark, while omitting references to the Fu Manchu character.

See also

In Spanish: Peligro amarillo para niños

In Spanish: Peligro amarillo para niños