Boxer Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Boxer Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Century of humiliation | |||||||

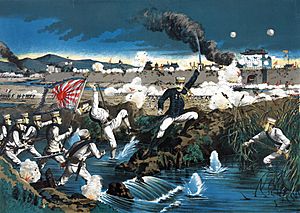

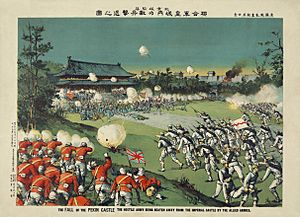

Top: US troops scale the walls of Beijing Middle: Japanese soldiers in the Battle of Tientsin Bottom: British and Japanese soldiers in the Battle of Beijing |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Eight-Nation Alliance

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Legations: Seymour Expedition: Gaselee Expedition: Occupation of Manchuria: Mutual Protection of Southeast China: |

Boxers: Qing dynasty: Commander in Chief: Hushenying: Tenacious Army: Resolute Army: Gansu Army: |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Seymour Expedition: 2,100–2,188 Gaselee Expedition: 18,000 China Relief Expedition: 2,500 Russian army in Manchuria: 100,000–200,000 |

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 32,000 Chinese Christians and 200 Western missionaries killed by Chinese Boxers in Northern China 100,000 total deaths in the conflict (both civilian and military included) |

|||||||

| Boxer Rebellion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 義和團運動 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 义和团运动 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Militia United in Righteousness Movement | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

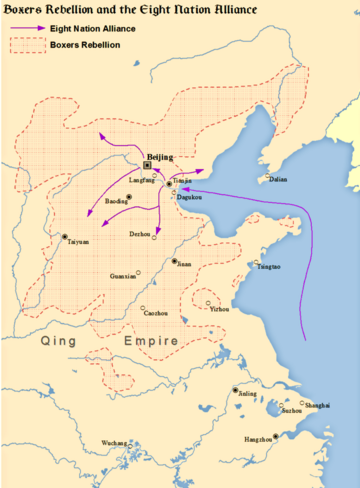

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists (Yìhéquán). The rebels were known as the "Boxers" in English because many of its members had practised Chinese martial arts, which at the time were referred to as "Chinese boxing".

After the Sino-Japanese War of 1895, villagers in North China feared the expansion of foreign spheres of influence and resented the extension of privileges to Christian missionaries, who used them to shield their followers. In 1898 North China experienced several natural disasters, including the Yellow River flooding and droughts, which Boxers blamed on foreign and Christian influence. Beginning in 1899, Boxers spread violence across Shandong and the North China Plain, destroying foreign property such as railroads and attacking or murdering Christian missionaries and Chinese Christians. The events came to a head in June 1900 when Boxer fighters, convinced they were invulnerable to foreign weapons, converged on Beijing with the slogan "Support the Qing government and exterminate the foreigners."

Diplomats, missionaries, soldiers and some Chinese Christians took refuge in the diplomatic Legation Quarter, which the Boxers besieged. An Eight-Nation Alliance of American, Austro-Hungarian, British, French, German, Italian, Japanese and Russian troops moved into China to lift the siege and on 17 June stormed the Dagu Fort at Tianjin. The Empress Dowager Cixi, who had initially been hesitant, supported the Boxers and on 21 June issued an Imperial Decree, a de facto declaration of war, on the invading powers. Chinese officialdom was split between those supporting the Boxers and those favouring conciliation, led by Prince Qing. The supreme commander of the Chinese forces, the Manchu General Ronglu (Junglu), later claimed he acted to protect the foreigners. Officials in the southern provinces ignored the imperial order to fight against foreigners.

The Eight-Nation Alliance, after initially being turned back by the Imperial Chinese military and Boxer militia, brought 20,000 armed troops to China. They defeated the Imperial Army in Tianjin and arrived in Beijing on 14 August, relieving the fifty-five day siege of the Legations. Plunder of the capital and the surrounding countryside ensued, along with summary execution of those suspected of being Boxers in retribution. The Boxer Protocol of 7 September 1901 provided for the execution of government officials who had supported the Boxers, provisions for foreign troops to be stationed in Beijing, and 450 million taels of silver—more than the government's annual tax revenue—to be paid as indemnity over the course of the next 39 years to the eight nations involved. The Qing dynasty's handling of the Boxer Rebellion further weakened their control over China, and led the dynasty to attempt major governmental reforms in the aftermath.

Contents

Background

Origins of the Boxers

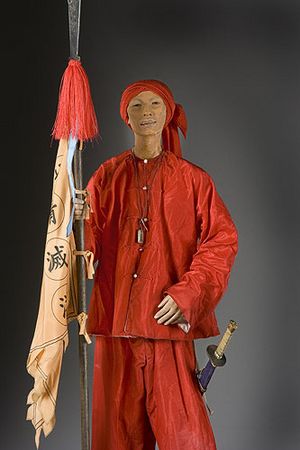

The Righteous and Harmonious Fists (Yihequan) arose in the inland sections of the northern coastal province of Shandong, a region which had long been plagued by social unrest, religious sects, and martial societies. American Christian missionaries were probably the first people who referred to the well-trained, athletic young men as the "Boxers", because of the martial arts which they practised and the weapons training which they underwent. Their primary practice was a type of spiritual possession which involved the whirling of swords, violent prostrations, and incantations to deities.

The opportunities to fight against Western encroachment and colonisation were especially attractive to unemployed village men, many of whom were teenagers. The tradition of possession and invulnerability went back several hundred years but took on special meaning against the powerful new weapons of the West. The Boxers, armed with rifles and swords, claimed supernatural invulnerability against cannons, rifle shots, and knife attacks. The Boxer groups popularly claimed that millions of soldiers would descend out of heaven to assist them in purifying China of foreign oppression.

In 1895, despite ambivalence toward their heterodox practices, Yuxian, a Manchu who was then prefect of Caozhou and would later become provincial governor, cooperated with the Big Swords Society, whose original purpose was to fight bandits. The German Catholic missionaries of the Society of the Divine Word had built up their presence in the area, partially by taking in a significant portion of converts who were "in need of protection from the law". On one occasion in 1895, a large bandit gang defeated by the Big Swords Society claimed to be Catholics to avoid prosecution. "The line between Christians and bandits became increasingly indistinct", remarks historian Paul Cohen.

Some missionaries such as George Stenz also used their privileges to intervene in lawsuits. The Big Swords responded by attacking Catholic properties and burning them. As a result of diplomatic pressure in the capital, Yuxian executed several Big Sword leaders but did not punish anyone else. More martial secret societies started emerging after this.

The early years saw a variety of village activities, not a broad movement with a united purpose. Martial folk-religious societies such as the Baguadao (Eight Trigrams) prepared the way for the Boxers. Like the Red Boxing school or the Plum Flower Boxers, the Boxers of Shandong were more concerned with traditional social and moral values, such as filial piety, than with foreign influences. One leader, Zhu Hongdeng (Red Lantern Zhu), started as a wandering healer, specialising in skin ulcers, and gained wide respect by refusing payment for his treatments. Zhu claimed descent from Ming dynasty emperors, since his surname was the surname of the Ming imperial family. He announced that his goal was to "Revive the Qing and destroy the foreigners" ("扶清滅洋 fu Qing mie yang").

The enemy was seen as foreign influence. They decided the "primary devils" were the Christian missionaries whilst the "secondary devils" were the Chinese converts to Christianity, which both had either to repent, be driven out or killed.

Causes of the conflict and the unrest

Escalating tensions caused Chinese to turn against "foreign devils" who scrambled for power in the late 19th century. The Western success at controlling China, growing anti-imperialist sentiment, and extreme weather conditions sparked the movement. A drought followed by floods in Shandong province in 1897–98 forced farmers to flee to cities and seek food.

A major cause of discontent in North China was missionary activity. The Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin) and the Convention of Peking, signed in 1860 after the Second Opium War, had granted foreign missionaries the freedom to preach anywhere in China and to buy land on which to build churches. On 1 November 1897, a band of armed men who were perhaps members of the Big Swords Society stormed the residence of a German missionary from the Society of the Divine Word and killed two priests. This attack is known as the Juye Incident. When Kaiser Wilhelm II received news of these murders, he dispatched the East Asia Squadron to occupy Jiaozhou Bay on the southern coast of the Shandong peninsula.

In December 1897, Wilhelm II declared his intent to seize territory in China, which triggered a "scramble for concessions" by which Britain, France, Russia and Japan also secured their own sphere of influence in China. Germany gained exclusive control of developmental loans, mining, and railway ownership in Shandong province. Russia gained influence of all territory north of the Great Wall, plus the previous tax exemption for trade in Mongolia and Xinjiang, economic powers similar to Germany's over Fengtian, Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces. France gained influence of Yunnan, most of Guangxi and Guangdong provinces, Japan over Fujian province. Britain gained influence of the whole Yangtze River Valley (defined as all provinces adjoining the Yangtze river as well as Henan and Zhejiang provinces), parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces and part of Tibet.

Only Italy's request for Zhejiang province was declined by the Chinese government. These do not include the lease and concession territories where the foreign powers had full authority. The Russian government militarily occupied their zone, imposed their law and schools, seized mining and logging privileges, settled their citizens, and even established their municipal administration on several cities.

In October 1898, a group of Boxers attacked the Christian community of Liyuantun village where a temple to the Jade Emperor had been converted into a Catholic church. Disputes had surrounded the church since 1869, when the temple had been granted to the Christian residents of the village. This incident marked the first time the Boxers used the slogan "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners" ("扶清滅洋 fu Qing mie yang") that later characterised them.

The "Boxers" called themselves the "Militia United in Righteousness" for the first time one year later, at the Battle of Senluo Temple (October 1899), a clash between Boxers and Qing government troops. By using the word "Militia" rather than "Boxers", they distanced themselves from forbidden martial arts sects and tried to give their movement the legitimacy of a group that defended orthodoxy.

Aggression toward missionaries and Christians drew sharp responses from diplomats protecting their nationals. In 1899, the French minister in Beijing helped the missionaries to obtain an edict granting official status to every order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, enabling local priests to support their people in legal or family disputes and bypass the local officials. After the German government took over Shandong, many Chinese feared that the foreign missionaries and possibly all Christian activities were imperialist attempts at "carving the melon", i.e., to colonise China piece by piece. A Chinese official expressed the animosity towards foreigners succinctly, "Take away your missionaries and your opium and you will be welcome."

The early growth of the Boxer movement coincided with the Hundred Days' Reform (11 June – 21 September 1898), in which progressive Chinese officials, with support from Protestant missionaries, persuaded the Guangxu Emperor to institute sweeping reforms. This alienated many conservative officials, whose opposition led Empress Dowager Cixi to intervene and reverse the reforms. The failure of the reform movement disillusioned many educated Chinese and thus further weakened the Qing government.

The national crisis was widely perceived as caused by "foreign aggression" inside, even though afterwards a majority of Chinese were grateful for the actions of the alliance. The Qing government was corrupt, common people often faced extortions from government officials and the government offered no protection from the violent actions of the Boxers.

Qing forces

The military of the Qing dynasty had been dealt a severe blow by the Sino-Japanese war and this had prompted military reform that was still in its early stages when the Boxer rebellion occurred and they were expected to fight.

The bulk of the fighting was conducted by the forces already around Zhili with troops from other provinces only arriving after the main fighting had ended.

| Army | The Boards of

War/Revenue (field troops only) |

Russian General

Staff (field troops only) |

E.H. Parker

(Zhili alone) |

The London Times

(Zhili alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 360,000 | 205,000 | 125,000–130,000 | 110,000–140,000 |

The failure of the Qing forces to withstand the allied forces was not surprising given the limited time for reform and the fact that the best troops of China were not committed to the fight remaining instead in Huguang and Shandong. The officer corps was noted as particularly deficient lacking basic knowledge of strategy and tactics, even those with training had not actively commanded troops in the field, though accusations of cowardice were minimal this was not the case in 1894–1895 a marked improvement as Chinese troops did not flee en masse as before. The regular soldiers were noted for their poor marksmanship and inaccuracy, the cavalry was ill-organised and was not utilised to its full extent, the Chinese still retained their belief of the superiority in defence as well as withdrawing as soon as they were flanked another deficiency attributable to their lack of combat experience and training as well as a lack of initiative from commanders who would rather retreat than counterattack. If led by courageous officers, the troops would often fight to the death as occurred under Nie Shicheng and Ma Yukun.

On the other hand, the Chinese artillery was noted as being excellent causing far more casualties than the infantry at Tianjin as their accurate fire hit their marks more often, they also proved themselves superior to allied artillery in counter-battery fire. The infantry for their part were commended for their good usage of cover and concealment in addition to their tenacity in resistance and good defensive works placed amongst favourable terrain as well as adapting to night attacks and conducting ruses de guerre.

Boxer War

Intensifying crisis

In January 1900, with a majority of conservatives in the imperial court, Empress Dowager Cixi changed her position on the Boxers and issued edicts in their defence, causing protests from foreign powers. In spring 1900, the Boxer movement spread rapidly north from Shandong into the countryside near Beijing. Boxers burned Christian churches, killed Chinese Christians and intimidated Chinese officials who stood in their way. American Minister Edwin H. Conger cabled Washington, "the whole country is swarming with hungry, discontented, hopeless idlers."

On 30 May the diplomats, led by British Minister Claude Maxwell MacDonald, requested that foreign soldiers come to Beijing to defend the legations. The Chinese government reluctantly acquiesced, and the next day a multinational force of 435 navy troops from eight countries debarked from warships and travelled by train from Dagu (Taku) to Beijing. They set up defensive perimeters around their respective missions.

On 5 June 1900 the railway line to Tianjin was cut by Boxers in the countryside, and Beijing was isolated. On 11 June at Yongding gate, the secretary of the Japanese legation, Sugiyama Akira, was attacked and killed by the soldiers of General Dong Fuxiang, who were guarding the southern part of the Beijing walled city. Armed with Mauser rifles but wearing traditional uniforms, Dong's troops had threatened the foreign legations in the fall of 1898 soon after arriving in Beijing, so much that United States Marines had been called to Beijing to guard the legations.

Kaiser Wilhelm II was so alarmed by the Chinese Muslim troops that he requested the Caliph Abdul Hamid II of the Ottoman Empire to find a way to stop the Muslim troops from fighting. The Caliph agreed to the Kaiser's request and sent Enver Pasha (not to be confused with the future Young Turk leader) to China in 1901, but the rebellion was over by that time.

On 11 June the first Boxer was seen in the Legation Quarter. The German Minister Clemens von Ketteler and German soldiers captured a Boxer boy and inexplicably executed him. In response, thousands of Boxers burst into the walled city of Beijing that afternoon and burned many of the Christian churches and cathedrals in the city, burning some victims alive. American and British missionaries took refuge in the Methodist Mission, and an attack there was repulsed by American Marines. The soldiers at the British Embassy and German legations shot and killed several Boxers. The Muslim Gansu braves and Boxers, along with other Chinese, then attacked and killed Chinese Christians around the legations in revenge for foreign attacks on Chinese.

Seymour Expedition

As the situation grew more violent, the Eight Powers authorities at Dagu dispatched a second multinational force to Beijing on 10 June 1900. This force of 2,000 sailors and marines was under the command of Vice Admiral Edward Seymour RN, the largest contingent being British. The force moved by train from Dagu to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway had been severed between Tianjin and Beijing. Seymour resolved to continue forward by rail to the break and repair the railway, or progress on foot from there, if necessary, as it was only 120 km from Tianjin to Beijing.

The court then replaced Prince Qing at the Zongli Yamen with Manchu Prince Duan, a member of the imperial Aisin Gioro clan (foreigners called him a "Blood Royal"), who was anti-foreigner and pro-Boxer. He soon ordered the Imperial army to attack the foreign forces. Confused by conflicting orders from Beijing, General Nie Shicheng let Seymour's army pass by in their trains.

After leaving Tianjin, the force quickly reached Langfang, but the railway was destroyed there. Seymour's engineers tried to repair the line, but the force found itself surrounded, as the railway in both behind directions was destroyed. They were attacked from all sides by Chinese irregulars and Imperial troops. Five thousand of Dong Fuxiang's "Gansu Braves" and an unknown number of "Boxers" won a costly but major victory over Seymour's troops at the Battle of Langfang on 18 June.

The Seymour force could not locate the Chinese artillery, which was raining shells upon their positions. Chinese troops employed mining, engineering, flooding, and simultaneous attacks. The Chinese also employed pincer movements, ambushes, and sniping with some success.

On 18 June Seymour learned of attacks on the Legation Quarter in Beijing, and decided to continue advancing, this time along the Beihe River, toward Tongzhou, 25 km (16 mi) from Beijing. By 19 June the force was halted by progressively stiffening resistance and started to retreat southward along the river with over 200 wounded.

The force was now very low on food, ammunition, and medical supplies. They happened upon the Great Xigu Arsenal, a hidden Qing munitions cache of which the Eight Powers had had no knowledge until then.

There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant slipped through the Boxer and Imperial lines, reached Tianjin, and informed the Eight Powers of Seymour's predicament. His force was surrounded by Imperial troops and Boxers, attacked nearly around the clock, and at the point of being overrun. The Eight Powers sent a relief column from Tianjin of 1,800 men (900 Russian troops from Port Arthur, 500 British seamen, and other assorted troops). On 25 June the relief column reached Seymour. The Seymour force destroyed the Arsenal: they spiked the captured field guns and set fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimated £3 million worth). The Seymour force and the relief column marched back to Tientsin, unopposed, on 26 June. Seymour's casualties during the expedition were 62 killed and 228 wounded.

Conflicting attitudes within the Qing imperial court

Meanwhile, in Beijing, on 16 June, Empress Dowager Cixi summoned the imperial court for a mass audience and addressed the choice between using the Boxers to evict the foreigners from the city and seeking a diplomatic solution. In response to a high official who doubted the efficacy of the Boxers, Cixi replied that both sides of the debate at the imperial court realised that popular support for the Boxers in the countryside was almost universal and that suppression would be both difficult and unpopular, especially when foreign troops were on the march.

Siege of the Beijing legations

On 15 June, Qing imperial forces deployed electric mines in the Beihe River (Peiho) to prevent the Eight-Nation Alliance from sending ships to attack. With a difficult military situation in Tianjin and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June they took the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore. When Cixi received an ultimatum that same day demanding that China surrender total control over all its military and financial affairs to foreigners, she defiantly stated before the entire Grand Council, "Now they [the Powers] have started the aggression, and the extinction of our nation is imminent. If we just fold our arms and yield to them, I would have no face to see our ancestors after death. If we must perish, why don't we fight to the death?" It was at this point that Cixi began to blockade the legations with the armies of the Peking Field Force, which began the siege. Cixi stated that "I have always been of the opinion, that the allied armies had been permitted to escape too easily in 1860. Only a united effort was then necessary to have given China the victory. Today, at last, the opportunity for revenge has come", and said that millions of Chinese would join the cause of fighting the foreigners since the Manchus had provided "great benefits" on China. On receipt of the news of the attack on the Dagu Forts on 19 June, Empress Dowager Cixi immediately sent an order to the legations that the diplomats and other foreigners depart Beijing under escort of the Chinese army within 24 hours.

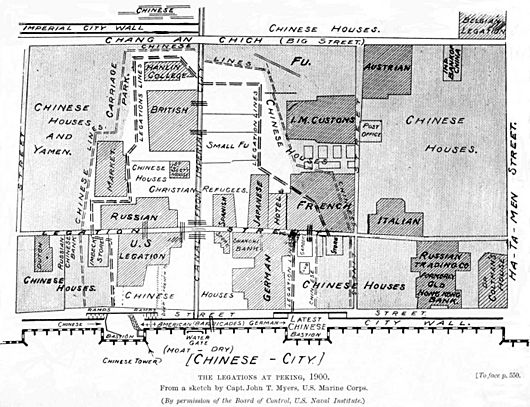

The next morning, diplomats from the besieged legations met to discuss the Empress's offer. The majority quickly agreed that they could not trust the Chinese army. Fearing that they would be killed, they agreed to refuse the Empress's demand. The German Imperial Envoy, Baron Clemens von Ketteler, was infuriated with the actions of the Chinese army troops and determined to take his complaints to the royal court. Against the advice of the fellow foreigners, the baron left the legations with a single aide and a team of porters to carry his sedan chair. On his way to the palace, von Ketteler was killed on the streets of Beijing by a Manchu captain. His aide managed to escape the attack and carried word of the baron's death back to the diplomatic compound. At this news, the other diplomats feared they also would be murdered if they left the legation quarter and they chose to continue to defy the Chinese order to depart Beijing. The legations were hurriedly fortified. Most of the foreign civilians, which included a large number of missionaries and businessmen, took refuge in the British legation, the largest of the diplomatic compounds. Chinese Christians were primarily housed in the adjacent palace (Fu) of Prince Su, who was forced to abandon his property by the foreign soldiers.

On 21 June, Empress Dowager Cixi issued an Imperial Decree stating that hostilities had begun and ordering the regular Chinese army to join the Boxers in their attacks on the invading troops. This was a de facto declaration of war, but the Allies also made no formal declaration of war. Regional governors in the south, who commanded substantial modernised armies, such as Li Hongzhang at Canton, Yuan Shikai in Shandong, Zhang Zhidong at Wuhan and Liu Kunyi at Nanjing, formed the Mutual Defense Pact of the Southeastern Provinces. They refused to recognise the imperial court's declaration of war, which they declared a luan-ming (illegitimate order) and withheld knowledge of it from the public in the south. Yuan Shikai used his own forces to suppress Boxers in Shandong, and Zhang entered into negotiations with the foreigners in Shanghai to keep his army out of the conflict. The neutrality of these provincial and regional governors left the majority of Chinese military forces out of the conflict.

The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were located in the Beijing Legation Quarter south of the Forbidden City. The Chinese army and Boxer irregulars besieged the Legation Quarter from 20 June to 14 August 1900. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers, marines and sailors from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge there. Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and military guards defended the compound with small arms, three machine guns, and one old muzzle-loaded cannon, which was nicknamed the International Gun because the barrel was British, the carriage Italian, the shells Russian and the crew American. Chinese Christians in the legations led the foreigners to the cannon and it proved important in the defence. Also under siege in Beijing was the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) of the Catholic Church. The Beitang was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 Catholic foreign priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties from lack of food and from mines which the Chinese exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound. The number of Chinese soldiers and Boxers besieging the Legation Quarter and the Beitang is unknown. Manchu Prince Zaiyi's Manchu bannermen in the Tiger and Divine Corps led attacks against the Catholic cathedral church. Manchu official Qixiu 啟秀 also led attacks against the cathedral.

On 22 and 23 June, Chinese soldiers and Boxers set fire to areas north and west of the British Legation, using it as a "frightening tactic" to attack the defenders. The nearby Hanlin Academy, a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world", caught fire. Each side blamed the other for the destruction of the invaluable books it contained.

After the failure to burn out the foreigners, the Chinese army adopted an anaconda-like strategy. The Chinese built barricades surrounding the Legation Quarter and advanced, brick by brick, on the foreign lines, forcing the foreign legation guards to retreat a few feet at a time. This tactic was especially used in the Fu, defended by Japanese and Italian sailors and soldiers, and inhabited by most of the Chinese Christians. Fusillades of bullets, artillery and firecrackers were directed against the Legations almost every night—but did little damage. Sniper fire took its toll among the foreign defenders. Despite their numerical advantage, the Chinese did not attempt a direct assault on the Legation Quarter although in the words of one of the besieged, "it would have been easy by a strong, swift movement on the part of the numerous Chinese troops to have annihilated the whole body of foreigners ... in an hour." American missionary Frank Gamewell and his crew of "fighting parsons" fortified the Legation Quarter, but impressed Chinese Christians to do most of the physical labour of building defences.

The Germans and the Americans occupied perhaps the most crucial of all defensive positions: the Tartar Wall. Holding the top of the 45 ft (14 m) tall and 40 ft (12 m) wide wall was vital. The German barricades faced east on top of the wall and 400 yd (370 m) west were the west-facing American positions. The Chinese advanced toward both positions by building barricades even closer. "The men all feel they are in a trap", said the American commander, Capt. John T. Myers, "and simply await the hour of execution." On 30 June, the Chinese forced the Germans off the Wall, leaving the American Marines alone in its defence.

At the same time, a Chinese barricade was advanced to within a few feet of the American positions, and it became clear that the Americans had to abandon the wall or force the Chinese to retreat. At 2 am on 3 July, 56 British, Russian and American marines and sailors, under the command of Myers, launched an assault against the Chinese barricade on the wall. The attack caught the Chinese sleeping, killed about 20 of them, and expelled the rest of them from the barricades. The Chinese did not attempt to advance their positions on the Tartar Wall for the remainder of the siege.

Sir Claude MacDonald said 13 July was the "most harassing day" of the siege. The Japanese and Italians in the Fu were driven back to their last defence line. The Chinese detonated a mine beneath the French Legation pushing the French and Austrians out of most of the French Legation. On 16 July, the most capable British officer was killed and the journalist George Ernest Morrison was wounded. But American Minister Edwin Hurd Conger established contact with the Chinese government and on 17 July, an armistice was declared by the Chinese.

Officials and commanders at cross purposes

The Manchu General Ronglu concluded that it was futile to fight all of the powers simultaneously and declined to press home the siege. The Manchu Zaiyi (Prince Duan), an anti-foreign friend of Dong Fuxiang, wanted artillery for Dong's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from attacking. Ronglu forced Dong Fuxiang and his troops to pull back from completing the siege and destroying the legations, thereby saving the foreigners and making diplomatic concessions. Ronglu and Prince Qing sent food to the legations and used their Manchu Bannermen to attack the Muslim Gansu Braves ("Kansu Braves" in the spelling of the time) of Dong Fuxiang and the Boxers who were besieging the foreigners. They issued edicts ordering the foreigners to be protected, but the Gansu warriors ignored it, and fought against Bannermen who tried to force them away from the legations. The Boxers also took commands from Dong Fuxiang. Ronglu also deliberately hid an Imperial Decree from General Nie Shicheng. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers because of the foreign invasion, and also because the population was suffering. Due to Ronglu's actions, General Nie continued to fight the Boxers and killed many of them even as the foreign troops were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers. Because parts of the railway were saved under Ronglu's orders, the foreign invasion army was able to transport itself into China quickly. General Nie committed thousands of troops against the Boxers instead of against the foreigners. Nie was already outnumbered by the Allies by 4,000 men. General Nie was blamed for attacking the Boxers, as Ronglu let Nie take all the blame. At the Battle of Tianjin (Tientsin), General Nie decided to sacrifice his life by walking into the range of Allied guns.

Xu Jingcheng, who had served as the Qing Envoy to many of the same states under siege in the Legation Quarter, argued that "the evasion of extraterritorial rights and the killing of foreign diplomats are unprecedented in China and abroad." Xu and five other officials urged Empress Dowager Cixi to order the repression of Boxers, the execution of their leaders, and a diplomatic settlement with foreign armies. The Empress Dowager, outraged, sentenced Xu and the five others to death for "willfully and absurdly petitioning the Imperial Court" and "building subversive thought." .....

Reflecting this vacillation, some Chinese soldiers were quite liberally firing at foreigners under siege from its very onset. Cixi did not personally order imperial troops to conduct a siege, and on the contrary had ordered them to protect the foreigners in the legations. Prince Duan led the Boxers to loot his enemies within the imperial court and the foreigners, although imperial authorities expelled Boxers after they were let into the city and went on a looting rampage against both the foreign and the Qing imperial forces. Older Boxers were sent outside Beijing to halt the approaching foreign armies, while younger men were absorbed into the Muslim Gansu army.

With conflicting allegiances and priorities motivating the various forces inside Beijing, the situation in the city became increasingly confused. The foreign legations continued to be surrounded by both Qing imperial and Gansu forces. While Dong Fuxiang's Gansu army, now swollen by the addition of the Boxers, wished to press the siege, Ronglu's imperial forces seem to have largely attempted to follow Empress Dowager Cixi's decree and protect the legations. However, to satisfy the conservatives in the imperial court, Ronglu's men also fired on the legations and let off firecrackers to give the impression that they, too, were attacking the foreigners. Inside the legations and out of communication with the outside world, the foreigners simply fired on any targets that presented themselves, including messengers from the imperial court, civilians and besiegers of all persuasions. Dong Fuxiang was denied artillery held by Ronglu which stopped him from levelling the legations, and when he complained to Empress Dowager Cixi on 23 June, she dismissively said that "Your tail is becoming too heavy to wag." The Alliance discovered large amounts of unused Chinese Krupp artillery and shells after the siege was lifted.

Gaselee Expedition

| Forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance Relief of the Legations  left to right: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan |

|||

| Countries | Warships (units) |

Marines (men) |

Army (men) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 540 | 20,300 | |

| 10 | 750 | 12,400 | |

| 8 | 2,020 | 10,000 | |

| 5 | 390 | 3,130 | |

| 2 | 295 | 3,125 | |

| 5 | 600 | 300 | |

| 2 | 80 | 2,500 | |

| 4 | 296 | unknown | |

| Total | 54 | 4,971 | 51,755 |

Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. Several international forces were sent to the capital, with varying success, and the Chinese forces were ultimately defeated by the Eight-Nation Alliance of Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Independent of the alliance, the Netherlands dispatched three cruisers in July to protect its citizens in Shanghai.

British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaselee acted as the commanding officer of the Eight-Nation Alliance, which eventually numbered 55,000. The main contingent was composed of Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), U.S. (3,420), German (900), Italian (80), Austro-Hungarian (75) and anti-Boxer Chinese troops. The "First Chinese Regiment" (Weihaiwei Regiment) which was praised for its performance, consisted of Chinese collaborators serving in the British military. Notable events included the seizure of the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by British Commander Roger Keyes. Among the foreigners besieged in Tianjin was a young American mining engineer named Herbert Hoover, who would go on to become the 31st President of the United States.

The international force finally captured Tianjin on 14 July. The international force suffered its heaviest casualties of the Boxer Rebellion in the Battle of Tianjin. With Tianjin as a base, the international force marched from Tianjin to Beijing, about 120 km, with 20,000 allied troops. On 4 August, there were approximately 70,000 Qing imperial troops and anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. The allies only encountered minor resistance, fighting battles at Beicang and Yangcun. At Yangcun, the 14th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. The weather was a major obstacle. Conditions were extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 42 °C (108 °F). These high temperatures and insects plagued the Allies. Soldiers became dehydrated and horses died. Chinese villagers killed Allied troops who searched for wells.

The heat killed Allied soldiers, who foamed at the mouth. The tactics along the way were gruesome on either side. ..... Cossacks were reported to have killed Chinese civilians almost automatically and Japanese kicked a Chinese soldier to death. The Chinese responded to the Alliance's atrocities with similar acts of violence and cruelty, especially towards captured Russians. Lieutenant Smedley Butler saw the remains of two Japanese soldiers nailed to a wall, who had their tongues cut off and their eyes gouged. Lieutenant Butler was wounded during the expedition in the leg and chest, later receiving the Brevet Medal in recognition for his actions.

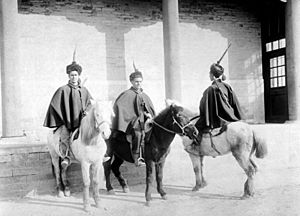

The international force reached Beijing on 14 August. Following the defeat of Beiyang army in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese government had invested heavily in modernising the imperial army, which was equipped with modern Mauser repeater rifles and Krupp artillery. Three modernised divisions consisting of Manchu Bannermen protected the Beijing Metropolitan region. Two of them were under the command of the anti-Boxer Prince Qing and Ronglu, while the anti-foreign Prince Duan commanded the ten-thousand-strong Hushenying, or "Tiger Spirit Division", which had joined the Gansu Braves and Boxers in attacking the foreigners. It was a Hushenying captain who had assassinated the German diplomat, Ketteler. The Tenacious Army under Nie Shicheng received Western style training under German and Russian officers in addition to their modernised weapons and uniforms. They effectively resisted the Alliance at the Battle of Tientsin before retreating and astounded the Alliance forces with the accuracy of their artillery during the siege of the Tianjin concessions (the artillery shells failed to explode upon impact due to corrupt manufacturing). The Gansu Braves under Dong Fuxiang, which some sources described as "ill disciplined", were armed with modern weapons but were not trained according to Western drill and wore traditional Chinese uniforms. They led the defeat of the Alliance at Langfang in the Seymour Expedition and were the most ferocious in besieging the Legations in Beijing.

The British won the race among the international forces to be the first to reach the besieged Legation Quarter. The U.S. was able to play a role due to the presence of U.S. ships and troops stationed in Manila since the U.S. conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish–American War and the subsequent Philippine–American War. In the U.S. military, the action in the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition. United States Marines scaling the walls of Beijing is an iconic image of the Boxer Rebellion.

The British Army reached the legation quarter on the afternoon of 14 August and relieved the Legation Quarter. The Beitang was relieved on 16 August, first by Japanese soldiers and then, officially, by the French.

Evacuation of the Qing imperial court from Beijing to Xi'an

In the early hours of 15 August, just as the Foreign Legations were being relieved, Empress Dowager Cixi, dressed in the padded blue cotton of a farm woman, the Guangxu Emperor, and a small retinue climbed into three wooden ox carts and escaped from the city covered with rough blankets. Legend has it that the Empress Dowager then either ordered that the Guangxu Emperor's favourite concubine, Consort Zhen, be thrown down a well in the Forbidden City or tricked her into drowning herself. The journey was made all the more arduous by the lack of preparation, but the Empress Dowager insisted this was not a retreat, rather a "tour of inspection." After weeks of travel, the party arrived in Xi'an in Shaanxi province, beyond protective mountain passes where the foreigners could not reach, deep in Chinese Muslim territory and protected by the Gansu Braves. The foreigners had no orders to pursue the Empress Dowager, so they decided to stay put.

Russian invasion of Manchuria

The Russian Empire and the Qing Dynasty had maintained a long peace, starting with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, but Russian forces took advantage of Chinese defeats to impose the Aigun Treaty of 1858 and the Treaty of Peking of 1860 which ceded formerly Chinese territory in Manchuria to Russia, much of which is held by Russia to the present day (Primorye). The Russians aimed for control over the Amur River for navigation, and the all-weather ports of Dairen and Port Arthur in the Liaodong peninsula. The rise of Japan as an Asian power provoked Russia's anxiety, especially in light of expanding Japanese influence in Korea. Following Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895, the Triple Intervention of Russia, Germany and France forced Japan to return the territory won in Liaodong, leading to a de facto Sino-Russian alliance.

Local Chinese in Manchuria were incensed at these Russian advances and began to harass Russians and Russian institutions, such as the Chinese Eastern Railway. In June 1900, the Chinese bombarded the town of Blagoveshchensk on the Russian side of the Amur. The Czar's government used the pretext of Boxer activity to move some 200,000 troops into the area to crush the Boxers. The Chinese used arson to destroy a bridge carrying a railway and a barracks on 27 July. The Boxers destroyed railways and cut lines for telegraphs and burned the Yantai mines.

The Chinese Honghuzi bandits of Manchuria, who had fought alongside the Boxers in the war, did not stop when the Boxer rebellion was over, and continued guerrilla warfare against the Russian occupation up to the Russo-Japanese war when the Russians were defeated by Japan.

Massacre of missionaries and Chinese Christians

Orthodox, Protestant, and Catholic missionaries and their Chinese parishioners were massacred throughout northern China, some by Boxers and others by government troops and authorities. After the declaration of war on Western powers in June 1900, Yuxian, who had been named governor of Shanxi in March of that year, implemented a brutal anti-foreign and anti-Christian policy. On 9 July, reports circulated that he had executed forty-four foreigners (including women and children) from missionary families whom he had invited to the provincial capital Taiyuan under the promise to protect them. Although the purported eyewitness accounts have recently been questioned as improbable, this event became a notorious symbol of Chinese anger, known as the Taiyuan Massacre. The Baptist Missionary Society, based in England, opened its mission in Shanxi in 1877. In 1900 all its missionaries there were killed, along with all 120 converts. By the summer's end, more foreigners and as many as 2,000 Chinese Christians had been put to death in the province. Journalist and historical writer Nat Brandt has called the massacre of Christians in Shanxi "the greatest single tragedy in the history of Christian evangelicalism."

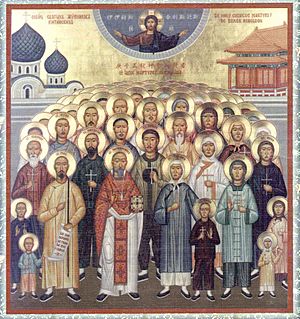

During the Boxer Rebellion as a whole, a total of 136 Protestant missionaries and 53 children were killed, and 47 Catholic priests and nuns, 30,000 Chinese Catholics, 2,000 Chinese Protestants, and 200 to 400 of the 700 Russian Orthodox Christians in Beijing were estimated to have been killed. Collectively, the Protestant dead were called the China Martyrs of 1900. 222 of Russian Christian Chinese Martyrs including St. Metrophanes were locally canonised as New Martyrs on 22 April 1902, after Archimandrite Innocent (Fugurovsky), head of the Russian Orthodox Mission in China, solicited the Most Holy Synod to perpetuate their memory. This was the first local canonisation for more than two centuries. The Boxers went on to murder Christians across 26 prefectures.

Aftermath

Reparations

After the capture of Peking by the foreign armies, some of Empress Dowager Cixi's advisers advocated that the war be carried on, arguing that China could have defeated the foreigners as it was disloyal and traitorous people within China who allowed Beijing and Tianjin to be captured by the Allies, and that the interior of China was impenetrable. They also recommended that Dong Fuxiang continue fighting. The Empress Dowager Cixi was practical, however, and decided that the terms were generous enough for her to acquiesce when she was assured of her continued reign after the war and that China would not be forced to cede any territory.

On 7 September 1901, the Qing imperial court agreed to sign the "Boxer Protocol" also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China. The protocol ordered the execution of 10 high-ranking officials linked to the outbreak and other officials who were found guilty for the slaughter of foreigners in China. Alfons Mumm (Freiherr von Schwarzenstein), Ernest Satow and Komura Jutaro signed on behalf of Germany, Britain and Japan, respectively.

China was fined war reparations of 450,000,000 taels of fine silver (≈540,000,000 troy ounces (17,000 t) @ 1.2 ozt/tael) for the loss that it caused. The reparation was to be paid by 1940, within 39 years, and would be 982,238,150 taels with interest (4 per cent per year) included. To help meet the payment it was agreed to increase the existing tariff from an actual 3.18 to 5 per cent, and to tax hitherto duty-free merchandise. The sum of reparation was estimated by the Chinese population (roughly 450 million in 1900), to let each Chinese pay one tael. Chinese custom income and salt taxes guaranteed the reparation. China paid 668,661,220 taels of silver from 1901 to 1939, equivalent in 2010 to ≈US$61 billion on a purchasing power parity basis.

A large portion of the reparations paid to the United States was diverted to pay for the education of Chinese students in U.S. universities under the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. To prepare the students chosen for this program an institute was established to teach the English language and to serve as a preparatory school. When the first of these students returned to China, they undertook the teaching of subsequent students; from this institute was born Tsinghua University.

The China Inland Mission lost more members than any other missionary agency: 58 adults and 21 children were killed. However, in 1901, when the allied nations were demanding compensation from the Chinese government, Hudson Taylor refused to accept payment for loss of property or life in order to demonstrate the meekness and gentleness of Christ to the Chinese.

The Belgian Catholic vicar apostolic of Ordos, Msgr. Alfons Bermyn wanted foreign troops garrisoned in Inner Mongolia, but the Governor refused. Bermyn petitioned the Manchu Enming to send troops to Hetao where Prince Duan's Mongol troops and General Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops allegedly threatened Catholics. It turned out that Bermyn had created the incident as a hoax. Western Catholic missionaries forced Mongols to give up their land to Han Chinese Catholics as part of the Boxer indemnities according to Mongol historian Shirnut Sodbilig. Mongols had participated in attacks against Catholic missions in the Boxer rebellion.

The Qing government did not capitulate to all the foreign demands. The Manchu governor Yuxian, was executed, but the imperial court refused to execute the Han Chinese General Dong Fuxiang, although he had also encouraged the killing of foreigners during the rebellion. Empress Dowager Cixi intervened when the Alliance demanded him executed and Dong was only cashiered and sent back home. Instead, Dong lived a life of luxury and power in "exile" in his home province of Gansu. Upon Dong's death in 1908, all honours which had been stripped from him were restored and he was given a full military burial.

Long-term consequences

The European great powers ceased their ambitions of colonising China since they had learned from the Boxer rebellions that the best way to deal with China was through the ruling dynasty, rather than directly with the Chinese people (a sentiment embodied in the adage: "The people are afraid of officials, the officials are afraid of foreigners, and the foreigners are afraid of the people") (Chinese: 老百姓怕官,官怕洋鬼子,洋鬼子怕老百姓), and they even briefly assisted the Qing in their war against the Japanese to prevent Japanese domination in the region.

Concurrently, the period marks the decline of European great power interference in Chinese affairs, with the Japanese replacing the Europeans as the dominant power for their lopsided involvement in the war against the Boxers as well as their victory in the First Sino-Japanese War. With the toppling of the Qing that followed and the rise of the Nationalist Kuomintang, European sway in China was reduced to symbolic status. After replacing Russian influence in the southern half of Manchuria as a result of the Russo-Japanese War, Japan came to dominate Asian affairs militarily and culturally with many of the Chinese scholars also educated in Japan, the most prominent example being Sun Yat-Sen, who would later create the Nationalist Kuomintang in China.

In October 1900, Russia occupied the provinces of Manchuria, a move that threatened Anglo-American hopes of maintaining the country's openness to commerce under the Open Door Policy.

Japan's clash with Russia over Liaodong and other provinces in eastern Manchuria, because of the Russian refusal to honour the terms of the Boxer protocol that called for their withdrawal, led to the Russo-Japanese War when two years of negotiations broke down in February 1904. The Russian Lease of the Liaodong (1898) was confirmed. Russia was ultimately defeated by an increasingly confident Japan.

Besides the compensation, Empress Dowager Cixi reluctantly started some reforms, despite her previous views. Known as the New Policies, which started in 1901, the imperial examination system for government service was eliminated, and the system of education through Chinese classics was replaced with a European liberal system that led to a university degree. Along with the formation of new military and police organisations, the reforms also simplified central bureaucracy and made a start at revamping taxation policies. After the deaths of Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor in 1908, the prince regent Zaifeng (Prince Chun), the Guangxu Emperor's brother, launched further reforms.

The effect on China was a weakening of the dynasty and its national defence capabilities. The government structure was temporarily sustained by the Europeans. Behind the international conflict, internal ideological differences between northern Chinese anti-foreign royalists and southern Chinese anti-Qing revolutionists were further deepened. The scenario in the last years of the Qing dynasty gradually escalated into a chaotic warlord era in which the most powerful northern warlords were hostile towards the southern revolutionaries, who overthrew the Qing monarchy in 1911. The rivalry was not fully resolved until the northern warlords were defeated by the Kuomintang's 1926–28 Northern Expedition. Prior to the final defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, all anti-Qing movements in the previous century, such as the Taiping Rebellion, had been successfully suppressed by the Qing.

In the Second Sino-Japanese War, when the Japanese asked the Muslim general Ma Hongkui to defect and become head of a Muslim puppet state, he responded that his relatives had been killed during the Battle of Peking, including his uncle Ma Fulu. Since Japanese troops made up most of the Alliance forces, there would be no co-operation with the Japanese.

Terminology

The name "Boxer Rebellion", concludes Joseph W. Esherick, a contemporary historian, is truly a "misnomer", for the Boxers "never rebelled against the Manchu rulers of China and their Qing dynasty" and the "most common Boxer slogan, throughout the history of the movement, was 'support the Qing, destroy the Foreign,' where 'foreign' clearly meant the foreign religion, Christianity, and its Chinese converts as much as the foreigners themselves." He adds that only after the movement was suppressed by the Allied Intervention did the foreign powers and influential Chinese officials both realise that the Qing would have to remain as the government of China in order to maintain order and collect taxes in order to pay the indemnity. Therefore, in order to save face for the Empress Dowager and the members of the imperial court, all argued that the Boxers were rebels and that the only support which the Boxers received from the imperial court came from a few Manchu princes. Esherick concludes that the origin of the term "rebellion" was "purely political and opportunistic", but it has had a remarkable staying power, particularly in popular accounts.

On 6 June 1900, The Times of London used the term "rebellion" in quotation marks, presumably to indicate its view that the rising was actually instigated by Empress Dowager Cixi. The historian Lanxin Xiang refers to the uprising as the "so called 'Boxer Rebellion,'" and he also states that "while peasant rebellion was nothing new in Chinese history, a war against the world's most powerful states was." Other recent Western works refer to the uprising as the "Boxer Movement", the "Boxer War" or the Yihetuan Movement, while Chinese studies refer to it as the 义和团运动 (Yihetuan yundong), that is, the "Yihetuan Movement." In his discussion of the general and legal implications of the terminology involved, the German scholar Thoralf Klein notes that all of the terms, including the Chinese terms, are "posthumous interpretations of the conflict." He argues that each term, whether it be "uprising", "rebellion" or "movement" implies a different definition of the conflict. Even the term "Boxer War", which has frequently been used by scholars in the West, raises questions. Neither side made a formal declaration of war. The imperial edicts on June 21 said that hostilities had begun and directed the regular Chinese army to join the Boxers against the Allied armies. This was a de facto declaration of war. The Allied troops behaved like soldiers who were mounting a punitive expedition in colonial style, rather than soldiers who were waging a declared war with legal constraints. The Allies took advantage of the fact that China had not signed "The Laws and Customs of War on Land", a key document signed at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference. They argued that China had violated provisions that they themselves ignored.

There is also a difference in terms referring to the combatants. The first reports which came from China in 1898 referred to the village activists as the "Yihequan", (Wade–Giles: I Ho Ch'uan). The earliest use of the term "Boxer" is contained in a letter which was written in Shandong in September 1899 by missionary Grace Newton. The context of the letter makes it clear that when it was written, "Boxer" was already a well-known term, probably coined by Arthur H. Smith or Henry Porter, two missionaries who were also residing in Shandong.

Media portrayal

By 1900, many new forms of media had matured, including illustrated newspapers and magazines, postcards, broadsides, and advertisements, all of which presented images of the Boxers and the invading armies. The rebellion was covered in the foreign illustrated press by artists and photographers. Paintings and prints were also published including Japanese woodblocks. In the following decades, the Boxers were a constant subject of comment. A sampling includes:

- In the Polish play The Wedding by Stanisław Wyspiański, first published on 16 March 1901, even before the rebellion was finally crushed, the character of Czepiec asks the journalist (Dziennikarz) one of the best-known questions in the history of Polish literature: "Cóż tam, panie, w polityce? Chińczyki trzymają się mocno!? ("How are things in politics, Mister? Are the Chinese holding out firmly!?").

- Liu E, The Travels of Lao Can sympathetically shows an honest official trying to carry out reforms and depicts the Boxers as sectarian rebels.

- The 1963 film 55 Days at Peking directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner and David Niven.

- In 1975 Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers studio produced the film Boxer Rebellion (Chinese: 八國聯軍; pinyin: bāguó liánjūn; Wade–Giles: Pa Kuo lien chun; literally "Eight-Nation Allied Army") under director Chang Cheh.

- The Last Empress (Boston, 2007), by Anchee Min, describes the long reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi in which the siege of the legations is one of the climactic events in the novel.

- Mo, Yan. Sandalwood Death. The viewpoint of villagers during Boxer Uprising.

See also

In Spanish: Levantamiento de los bóxers para niños

In Spanish: Levantamiento de los bóxers para niños

- Battle of Peking (1900)

- Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program

- Century of humiliation

- China Relief Expedition

- Donghak Rebellion, an anti-foreign, proto-nationalist uprising in pre-Japanese Korea

- Gengzi Guobian Tanci

- Imperial Decree on events leading to the signing of Boxer Protocol

- List of 1900–1930 publications on the Boxer Rebellion

- Xishiku Cathedral