Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871 |

|

|---|---|

| Location | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°03′24″N 118°14′16″W / 34.056583°N 118.237806°W |

| Date | 24 October 1871 |

| Target | Chinese immigrants |

|

Attack type

|

Massacre |

| Deaths | 19 |

| Perpetrators | Mob of around 500 non-Chinese men |

| Motive | Racially motivated, revenge for the accidental killing of Robert Thompson, a local rancher |

The Los Angeles Chinese massacre of 1871 was a racial massacre targeting Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles, California, United States that occurred on October 24, 1871. Approximately 500 white and Hispanic Americans attacked, harassed, robbed, and murdered the ethnic Chinese residents of the old Chinatown neighborhood of the city of Los Angeles, California. The massacre took place on Calle de los Negros, also referred to as "Negro Alley". The mob gathered after hearing that a policeman and a rancher had been killed as a result of a conflict between rival tongs, the Nin Yung, and Hong Chow. As news of their death spread across the city, fueling rumors that the Chinese community "were killing whites wholesale", more men gathered around the boundaries of Negro Alley. A few 21st-century sources have described this as the largest mass lynching in American history.

Nineteen Chinese immigrants were killed, fifteen of whom were later killed by the mob in the course of the riot. Those killed represented over 10% of the small Chinese population of Los Angeles at the time, which numbered 172 prior to the massacre. Ten men of the mob were prosecuted and eight were convicted of manslaughter in these deaths. The convictions were overturned on appeal due to technicalities.

Contents

Summary

The Los Angeles Chinese Massacre of 1871 was a violent, deadly event of unprecedented scale in Los Angeles, a town of 5,728 people per the 1870 census. A dispute internal to the Chinese community spilled out, leading to the "death of an American bystander and the wounding of a city policeman." This unfortunate incident sparked a frenzy of hatred and violent destruction centered in Calle de Los Negros, one of the town's oldest alleys and known for both its Chinese residences and businesses as well as its gambling dens. All but one of the Chinese victims killed in the massacre had not been involved in the original incident leading up to the massacre. After the confusion had settled, at least a hundred and fifty individuals were identified and directly linked to the violence "after an exhaustive coroner's inquest and the convening of a grand jury." The jury ultimately identified seven men for trial for their direct involvement in the death of one of the massacre victims. Judge Robert M. Widney secured convictions for lesser charges of manslaughter, ranging between two and nine years. However, an appeal to the California Supreme Court reversed the convictions and remitted the cases back to Widney's court. District Attorney Cameron E. Thom decided against retrying the cases and freed the accused in late spring of 1873. This blight in the history of Los Angeles has been referenced multiple times. Newspaper coverage and court coverage papers offer a comprehensive perspective regarding the criminal justice system's role on the backdrop of this unfortunate part of the city's history.

The Massacre's immediate cause traces to a fight between rival tongs, the Nin Yung, and Hong Chow. The rival factions fought over the alleged abduction of Yut Ho. The police had previously helped either side to capture and return escapee women in exchange for a fee. However, in the case of Ho, things had gotten out of control. For two days, the conflict escalated, leading to the death of Jesus Bilderrain and Robert Thompson, a police officer and a civilian, respectively. Not long after the fateful events, a crowd gathered around the Coronel Adobe, the events' location. Indiscriminate shooting ensued, violence leading to hundreds of injuries and deaths on both sides, and replicated in at least three other areas. Amid the melee, a few individuals, including a would-be District Judge, Robert M. Widney, tried to calm the situation. The Los Angeles Star reported that a Vigilance Committee addressed crowds at the point where Los Angeles Street, Calle de los Negros, and Main Street met. The police, led by Sheriff James F. Burns, were only able to arrest the situation hours later. After that, the criminal justice administration system began to piece together factual details to punish those responsible for the heinous acts.

The Massacre's primary basis is viewed mainly as the escalation of fights amidst the associates of two Chinese tongs over the possession of a woman called Yit Ho. The two groups' enemies ragged gunshots from 23rd to October 24, 1871, which killed a police officer from Los Angeles named Jesus Birderrain and Robert Thompson, a civilian. Reports presented disparities with some describing the event as murder. A few minutes after the dusk, a large gathering assembled everywhere in Coronel Block. According to reports, some in the crowd tried to calm the group and preclude the Chinese slayings including Robert M. Widney who would go on to become the district judge presiding over the cases of the seven murders involved in the Massacre. The last killing occurred at 9:30 pm, according to one news report. At the time, Sheriff James, with further community associates, had gained sufficient reinforcement; besides, it was four hours from the Massacre's commencement, scattering the crowd and guarding them throughout the night. The criminal justice dispensation structure, which was utterly defective in stopping the massive killing, started its investigations to seek facts to administer justice on the unprecedented inhuman act.

Background

Discrimination had been rising against the increasing number of Chinese immigrants living in California. It has been described as a root cause of the massacre. White residents of Los Angeles resented the expansion of the Chinese population, considering them an alien group. In 1863 the state legislature had passed a law that Asians (defined as Chinese, Mongolian, Indian, etc.) could not testify in court against whites, making them vulnerable to abuse and injustice, and putting them beyond reach of the law. In 1868 the United States had signed the Burlingame Treaty with the Chinese Empire, setting conditions for immigration. In this period, most Chinese workers who immigrated to the United States were men, intending to stay only temporarily. The small Chinese community in Los Angeles numbered fewer than 200, and 80% were men.

Another factor was the rough frontier nature of Los Angeles, which in the 1850s had a disproportionately high number of lynchings for its size, and an attachment to "popular justice" (this was also a period of violence across the country). It attracted transients from across the country.

In Los Angeles in the few days preceding the riot, two Chinese Tong factions, known as the Hong Chow and Nin Yung companies, had started a confrontation from a feud over the alleged abduction of a Chinese woman named Yut Ho (also documented as Ya Hit), who was announced in the paper as having married. Previously the police department had assisted the Tongs in keeping their confrontations over the women internal to the community, and sometimes capturing and returning women who had escaped, in exchange for payment by the Tongs, but in this case, things got out of hand. Two Chinese men were arrested for shooting at each other, and were released on bail, but the police kept watch on the Old Chinatown neighborhood. It had developed along Calle de los Negros, which was named in the colonial period.

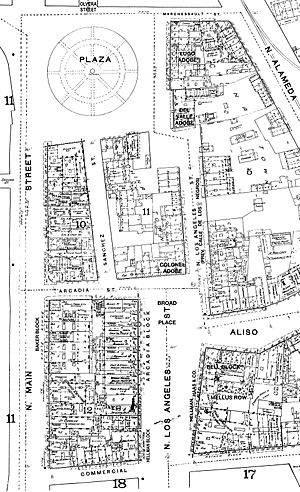

Calle de los Negros

Calle de los Negros was situated immediately northeast of Los Angeles's principal business district, running 500 feet (150 m) from the intersection of Arcadia Street to the plaza. The unpaved street was named by Spanish colonists for Californios (pre-annexation, Spanish-speaking Californians) of darker complexion (most likely of multiracial ancestry: Spanish, Native American, and African) who had originally lived there. The neighborhood had deteriorated into a slum by the time the first Chinatown of Los Angeles developed there in the 1860s.

Early 20th-century Los Angeles merchant Harris Newmark recalled in his memoir that Calle de los Negros was "as tough a neighborhood, in fact, as could be found anywhere." Los Angeles historian Morrow Mayo described it in 1933 as:

a dreadful thoroughfare, forty feet wide, running one whole block, filled entirely with saloons, gambling-houses, dance-halls, and cribs. It was crowded night and day with people of many races, male and female, all rushing and crowding along from one joint to another, from bar to bar, from table to table. There was a band in every joint, with harps, guitars, and other stringed instruments predominating.

The affray

On the afternoon of October 24, hearings were held in Justice Gray's Court concerning a shooting that occurred the day before in Negro Alley. Ah Choy (Won Choy), the brother of Yut Ho, and Won Yu Tak were accused of attempting to murder Yo Hing. And Yo Hing was accused to attempting to murder Ah Choy. Following the hearing, the parties returned to Negro Alley.

About one hour after the hearings, Constable Jesus Bilderrain went to the corner of the Coronel building and remained their for five minutes. Negro Alley was quiet, so he proceeded to Caswell & Ellis, on the opposite side of Arcadia Street. There he was told that Caswell had sold a large number of pistols during the last few days. Bilderrain left Caswell's and patrolled the area, going around the Pico House and stopping at Higby's Saloon, at the corner of Main and Arcadia.

According to an article published by Sam Yuen, Ah Choy was "eating his evening meal at a back part of a house on the east side of Negro Alley and heard a fuss, went out to the front door; Yo Hing and three others were around with pistols, and one of them shot Ah Choy in the neck. Yo Hing and the others then ran down the stairs at the corner" of Aliso and Los Angeles street.

Bilderrain was on horseback at the corner Main and Arcadia, speaking with Constable Estevan Sanchez, when he heard shots. He rode off in the direction of Negro Alley and instructed Sanchez to follow. He saw a group of Chinese men in the corridor of the Beaudry building shooting at one another. He started to follow one group of men that ran into the Beaudry Building and noticed a Chinese man laying wounded in the doorway. He proceeded to arrest a Chinese man with a gun, with the assistance of Ventura Lopez and Juan Espinosa. Another group of men had retreated to the Coronel Adobe and were shooting at Adolf Celis and Constable Hester. While escorting the arrested man to jail, Bilderrain passed in front of Sam Yuen's store, the third door from the corner in the Coronel Building, and saw a Chinese man with a pistol in his hand. He left Lopez and Espinosa intending to arrest the man at Sam Yuen's store. Bilderrain instructed Sanchez to arrest another man, but did not specify which one. The man at Sam Yuen's store fired at Bilderrain and immediately closed then the door. Bilderrain and Sanchez each went through different doors, through the house, and into a corral in the back of the Coronel Adobe. There they encountered a group of armed men. Bilderrain attempted to arrest the man he was following, was shot in the shoulder and dropped his pistol. Sanchez was fired upon, and shot three times in response. Both men then retreated. A group of men pursued Bilderrain through Gene Tong's store, and out of the building. Once outside, Bilderrain supported himself on a post at the corner of the corridor and blew his police whistle. Three men came out of the adobe and shot at Bilderrain before retreating back into the house. One of the shots hit Jose Mendibles in the leg. Sanchez came running down the corridor and was approaching the door of Sam Yuen's store. A crowd standing by Caswell & Ellis' warned him not to go near the door because they were firing from inside. Sanchez approached the door from the right, and looking inside saw Sam Yuen who raised his pistol; both men fired simultaneously. Other men inside fired also. At this time Robert Thompson appeared and approached the door from the left. Both Sanchez and Celis warned Thompson to stay back. Sanchez retreated to the corner to reload his gun, and was given another gun. While Sanchez was away from the door, Thompson fired two shots into Sam Yuen's store. One shot was fired from inside and hit Thompson. Thompson said "I'm killed." Celis helped take Thompson to Wollweber's Drug store where her later died. Sam Yuen and his brother escaped, disguised like cooks, with aprons. And Yo Hing hid in Alec's barber shop.

After the shooting had subsided, and the doors to the Coronel Adobe closed, Frank Baker, City Marshal, assigned men to guard the house with instructions to allow no Chinese men to leave. Men were placed on Sanchez street, Negro Alley, and at the Plaza. Lawmen came and went as a larger crowd gathered along the edges of Chinatown, acting as a guard to prevent any Chinese person from escaping. Informed of the growing crowd, three-term Mayor Cristobal Aguilar, a longtime politician in the city, also surveyed the situation and then left. When news of Thompson's death passed through the city, along with the rumor that the Chinese community in Negro Alley "were killing whites wholesale", more men gathered around the boundaries of Negro Alley.

The riot

The first victim of the mob was Ah Wing. The crowd captured Ah Wing, who appeared to have come from Beaudry's building. Marshal Baker searched him and found a "four barreled sharp-shooter, with one load out". Baker confiscated the gun and released him.

Ah Wing was captured again a short while later, this time armed with a hatchet. Constable Emil Harris took charge of Ah Wing. Harris and Charles Avery escorted Ah Wing towards the jail. A crowd of approximately 100 men followed them up Arcadia and Main street. Then, at the intersection of Main and Spring, Avery was hit from behind, the crowd took Ah Wing and held Harris. Ah Wing was led up to Tomlinson's Corral and there killed from the cross beam of the gate. This was the same gate where Michel Lachenais was killed less than a year before. Harris then returned to the Coronel Building.

Agustus Cates was standing guard on Arcadia street in front of the Coronel Adobe. The door started to open. Cates told the occupants to close the door, but they did not. So a police man ordered one of the guards to fire his Derringer at it. The door was closed and Cates and the others moved away from it. Later, when they had their back to the door, watching the other side of the street, the door opened and three shots were fired. Cates turned around just in time to see the door close again.

Later, another door opened, this time facing on Negro Alley. A Chinese man came rushing out, thirty or forty shots were fired. He made it less than ten feet before he fell. C. Dennuke stated during the Coroner's inquest that this man was Ah Cut. Another man inside the house, standing at a large window, drew a curtain aside, and several parties came up and fired into the window with shotguns and pistols.

According to Henry Hazard, there was considerable shooting at the building. Shortly afterward men started to scale the building with a ladder. He recognized Charles Austin as being the first to mount the building. At one point, Sheriff Burns counted 11 men on the roof. Various witnesses also identified Rufugio Botello, Jesus Martinez, J. C. Cox, Sam Carson, and "Curly" Crenshaw being on the roof. Men on the roof shot at the Chinese in the backyard of the building. Then someone passed up axes and the men started cutting holes in the roof. It was reported that ten holes had been cut. Men started firing through the ceiling into one of the rooms, causing the occupants to run out of the house.

J. C. Cox testified, one man ran out of the house, the mob on the street started firing. Cox saw him crawl back, and volunteered to go in and get the man out. He obtained a ball dipped in alcohol, lit it, and threw it into the room. He then went in, found the wounded man and carried him out and across the street. The crowd then mustered the courage to enter the building, found two Chinese men in that room and pulled them out. Hazard testified that at this point the crowd started breaking in the doors and removing the occupants; working their way towards the corner. The Daily Star reported the first door was battered down at approximately 8:45 P. M.

Groups of men started leading the Chinese away from Negro Alley. Marshal Baker, Sheriff Burns, officers Hester and Harris individually gave parties instructions to take the Chinese to jail for safety. Harris' impression was that the groups proceeded to the jail, even though he was likely aware Ah Wing had been killed. Some of the groups did in fact lead their captives safely to the county jail. But other groups led men to either Tomlinson's corral or John Goller's wagon shop to be killed. Henry Hazard and General John Baldwin remonstrated with the lynching parties to no avail; Hazard at Goller's shop, and Baldwin at Tomlinson's corral. One group of men, consisting of Walter White, John Lazzarovich, and brothers Robert and Walter Widney, managed to rescue four Chinese from the mob near Tomlinson's. Constable Billy Sands managed to rescue four; one from Antione Silva near Goller's shop. At about 9:20 P. M., Sheriff Burns addressed the crowd, and requested 25 volunteers to help preserve the peace and guard the building until the morning.

Events

Rioters climbed to the rooftops of buildings where Chinese immigrants resided, used pickaxes to puncture holes in the roofs, and shot at the people inside. Those who fled outside were shot at by gunmen on the roofs. Many were also beaten and tortured.

By the end of the riot:

The dead Chinese people in Los Angeles were hanging at three places near the heart of the downtown business section of the city; from the wooden awning over the sidewalk in front of a carriage shop; from the sides of two "prairie schooners" parked on the street around the corner from the carriage shop; and from the cross-beam of a wide gate leading into a lumberyard a few blocks away from the other two locations.

The mob ransacked practically every Chinese-occupied building on the block and attacked or robbed nearly every resident. A total of 19 Chinese immigrant men were killed by the mob.

Coroner's inquest

The inquest covered an entire four days and encompassed interviewing of various range of eyewitnesses. Disappointedly, no data from the inquest was ascertained, known hitherto, and newspaper feedbacks serving as the sole source of information. Firstly, the two interviews involving Robert Thompson, which took two hours, emerged to be broad and elaborate. Still, only a single observer, Constable Bilderrain, was examined. His description of the event was reliant on facts and was apprehensive that Thompson got shot in the process of assisting him. In the process of pursuing justice for the murdered Chinese victims, utterly innocent of the Massacre, seven men were sentenced in the law court, whether unquestionably guilt-ridden or not. The Supreme Court omitted the prosecution on Gene killings. Further, it is crystal clear that there was no basis in the High court verdict that compelled them to trust the sentenced demonstrators were blameless. The District Attorney and Judge felt in 1873 that it was becoming unrealistic and illogical to pursue new trials; the issue was called off. Since then, the Chinese community performs an exceptional prayer at the city in honor of the carnage and misfortune.

Grand jury and indictments

Following the coroner's inquest, Tong Yu, widow to Dr. Gene Tong, filed a complaint in the Justice Court, accusing Yo Hing, one of the tong leaders, of "inciting and participating" the Massacre that led to her husband's death. While Yo was initially held following the November 4 complaint, the Grand Jury could not link him directly with the events, and he was later released.

Four days after this complaint, "County Court Judge Ygnacio Sepulveda convened a special Grand Jury to investigate the events around to the Massacre." A jury composed of individuals of diverse backgrounds, Juan Jose (long-time resident), William Perry (building contractor), Kaspare Cohn (building contractor), William Henry (saddle maker and councilman), and Martin Sanchez (farmer), was constituted. Judge Sepulveda condemned the violence pattern in the strongest terms possible and challenged the jury to stand up to the occasion. The jury's report noted forty-nine indictments for felonies and murders (almost split halfway). The report highlighted full statements of the events leading to the Massacre. Immediately after the report's publication, A.R. Thompson, Charles Austin, and Charles Crawford (official records Edmund Crawford) were held. Another set of five individuals, Louis Mendel, Jesus Martinez, Andreas Soeur, Patrick McDonald, and D.W. Moody, were arrested and held. Three Chinese people and two whites were held, but for lesser charges, an additional five unnamed individuals were held.

Trials

The most famous case was People v. Kerren, in which the defendant was accused of shooting at two Chinese women, Cha Cha and Fan Cho, with a deadly assault weapon. Kerren was released on a $1,000 bail. Several other witness statements were full of objections by District Attorney Thom and defense counsels based on irrelevant leading questions. In People v. Quong Wan and Ah Yeng, Wan and Yeng were accused of being the originators of the riots and subsequently charged with the murder of Ah Coy. Coupled with these charges were rumors that the Chinese community had been on a gun-buying spree days before the Massacre and that some Chinese people were also expected in from San Francisco in readiness for a fight. In People v. Crenshaw, the case pursued the murder of Gene Tong. Later, all the cases were combined into one and attracted interest from both the public and the press.

While the convicted rioters were sentenced and taken to the San Quentin, a few other cases remained. Such cases included Fong Yen Ling, Sam Yuen, Yin Tuck, and Ah Ying v. The Mayor and Common Council of the City of Los Angeles, in which the merchants sued for damages to their stores during the Massacre. The Judge held that the city was not liable for the destruction of businesses and noted that such liability would only hold if the business owner had notified the city before the collapse. Several other cases were declined on the ground of lacking evidence. Thus, a review of the legal provisions was imperative to understand the court's decision despite the destruction of property and deaths.

Freeing of the rioters

In People v. Sam Yuen, Yuen was charged for shooting Jesus Bilderrain before Justice Trafford. The constable charged Yuen with “willfully, deliberately, feloniously and of malice aforethought, aiding, abetting, assisting, counseling and encouraging a Chinaman, identified as John Doe, to kill and murder". While an arrest warrant was issued for Bilderrain, Yuen could not be traced. When he returned in 1872, no warrant was served.

Complications further arose when a second warrant was issued. However, reports indicated that a post-Massacre addition to the force, Constable Frank Hurtley, arrested Yuen. Adolfo Celis testified that he had seen Yuen running behind another Chinese man as both entered the Coronel Block at the time of the violence. He narrated details that placed Yuen at the scene of the Massacre and confirmed his playing an active role. The Massacre brought to fore the protection of the minority through the laws of Los Angeles. At the same time, there was open prejudice against minorities. The judicial process, such as in the case of Sam Yuen, went on smoothly. A jury that determined its case based on race would have found Yuen liable. However, the court followed all the due process of the law, relied on witness testimonies, including the reversal of misleading accounts by Jesus Bilderrain. It can thus be concluded that due process of the law was followed.

There is, however, no clarity on whether the Massacre led to any positive advancements towards the fight against crime. Anti-Chinese hate flared in the weeks that followed. Overt anti-Chinese violence died naturally after the proceedings. This notwithstanding, however, anti-Chinese feelings persisted and were expressed more subtly.

Aftermath

Authorities arrested and prosecuted ten rioters. Eight were convicted of manslaughter at trial and sentenced to prison terms at San Quentin. Their convictions were overturned on appeal due to a legal technicality. The eight men convicted were:

- Alvarado, Esteban

- Austin, Charles

- Botello, Refugio

- Crenshaw, L. F.

- Johnson, A. R.

- Martinez, Jesus

- McDonald, Patrick M.

- Mendel, Louis

| Alvarado, Estefan (also Juan) | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to four years |

| Armanta, Thomas | Alleged to have stolen the diamond ring from Pe Ne Tong (Gene Tong) – Escaped from the county hospital on 2/21/72 |

| Austin, Charles | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to five years |

| Botello, Refugio | Indicted for murder - Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to two years

Admitted to bail in the sum of $5,000. The case was appealed to the State Supreme Court. |

| Carson, Samuel C. | Indicted for murder – Plead not guilty - People vs. Carson - Outcome unknown |

| Celis, Adolphus | Indicted for murder – Acquitted |

| Cox, J. C. | People vs. Cox. - Outcome unknown |

| Crawford, Edmond (also Edward) | Indicted for murder - Application for change of venire passed informally – Outcome unknown |

| Crenshaw, A. L. AKA Curley (also L. F.) | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to three years |

| Dominguez, Ramon | Indicted for murder - People vs. Ramon Dominguez - Outcome unknown |

| Johnson, A. R. | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to six years |

| Kerren, Richard | Two indictments for assault with a deadly weapon - Found not guilty on one count Jan 5, 1872

Case dismissed on the second count on the grounds that is would be impossible to obtain a conviction. |

| Martinez, Jesus | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to four years |

| McDonald, Patrick (also MacDonald) | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to five years |

| Mendell, Louis AKA Frenchy aka Fatty | Indicted for murder – Guilty of manslaughter - Sentenced to six years |

| Moody, D. W. (Dan.) | Indicted for murder – Acquitted |

| Ruiz, Ambrosio | Charged with participating in the riot arrested on 12/11/71 - People vs. Ambrosio Ruiz - Outcome unknown |

| Scott, J. G, | Indicted for murder - Outcome unknown |

| Silva, Antoine | Arrested during the Coroner's Inquest - Outcome unknown |

| Soeur, Andreas (Andres Sour/Saers) | Arrested - Case taken under consideration by the Grand Jury - Outcome unknown |

| Sotello, Carmen (also Carmen Lugo) | Arrested on the charge of being concerned in the riot and having robbed the Chinese doctor, Gene Long Tong of a gold watch and chain. – Admitted bail in the sum of $100 - Outcome unknown |

| Thompson, David | Arrested for burglary of the Episcopal Church and found to have stolen a watch from one of the victims killed at Goller's.- Guilty - Sentenced to six years |

| Ah Yeng | People vs. Ah Shaw et al. – Charged with the murder of Ah Coy - Acquitted |

| Lee Saow (Ah Shaw) - Outcome unknown | People vs. Ah Shaw et al. |

| Qong Wong | People vs. Ah Shaw et al. – Charged with the murder of Ah Coy - Acquitted |

| Yo Duc | People vs. Yo Duc - Outcome unknown |

| Yuen, Sam | People vs. Sam Yuen – Indicted for the murder of Robert Thompson - Acquitted |

The event was well-reported on the East Coast, and newspapers there described Los Angeles as a "blood stained Eden" after the riots. A growing movement of anti-Chinese discrimination in California climaxed in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Calle de los Negros was renamed as part of Los Angeles Street in 1877 and obliterated in its previous form in 1888 as Los Angeles Street was widened and extended to the Plaza. The Coronel Adobe where the Chinese massacre occurred was torn down in the late 1880s. As of 2021, the former site of the Coronel Adobe is approximately in the middle of North Los Angeles street, immediately east of the Garnier Building located at 419 North Los Angeles Street.

In popular culture

L.P. Leung wrote about a main character involved with the 1871 massacre in The Jade Pendant (2013). This has been adapted as a Chinese-produced film by the same name, which was released in 2017 in North America.

See also

In Spanish: Masacre de chinos de Los Ángeles para niños

In Spanish: Masacre de chinos de Los Ángeles para niños