Tongva facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,900+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, formerly Tongva | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity |

The Tongva ( TONG-və) are an Indigenous people of California from the Los Angeles Basin and the Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately 4,000 square miles (10,000 km2).

In the precolonial era, the people lived in as many as 100 villages and primarily identified by their village rather than by a pan-tribal name. During colonization, the Spanish referred to these people as Gabrieleño and Fernandeño, names derived from the Spanish missions built on their land: Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Tongva is the most widely circulated endonym among the people, used by Narcisa Higuera in 1905 to refer to inhabitants in the vicinity of Mission San Gabriel.

Along with the neighboring Chumash, the Tongva were the most influential people at the time of European colonization of the Americas. Over time, different communities came to speak distinct dialects of the Tongva language, part of the Takic subgroup of the Uto-Aztecan language family. There may have been five or more such languages (three on the southernmost Channel Islands and at least two on the mainland).

In the early 20th century, an extinction myth was purported about the Gabrieleño, who largely identified publicly as Mexican-American by this time. However, a close-knit community of the people remained in contact with one another between Tejon Pass and San Gabriel township into the 20th century. Since 2006, four organizations have claimed to represent the people:

- the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe, known as the "hyphen" group from the hyphen in their name;

- the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe, known as the "slash" group;

- the Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians; and

- the Gabrieleño/Tongva Tribal Council.

In 2008, more than 1,700 people identified as Tongva or claimed partial ancestry. In 2013, it was reported that the four Tongva groups that have applied for federal recognition had more than 3,900 members in total. The Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy was established for the rematriation of Tongva homelands. In 2022, a 1-acre site was returned to the conservancy in Altadena, which marked the first time the Tongva had land in Los Angeles County in 200 years.

Contents

Geography

Tongva territories border those of numerous other tribes in the region. The historical Tongva lands made up what is now called "the coastal region of Los Angeles County, the northwest portion of Orange County and off-lying islands.” In 1962 Curator Bernice Johnson, of Southwest Museum, asserted that the northern bound was somewhere between Topanga and Malibu (perhaps the vicinity of Malibu Creek) and the southern bound was Orange County’s Aliso Creek.

Name

Tongva

The word Tongva was coined by C. Hart Merriam in 1905 from numerous informants. These included Mrs. James Rosemyre (née Narcisa Higuera) (Gabrileño), who lived around Fort Tejon, near Bakersfield. Merriam's orthography makes it clear that the endonym would be pronounced TONG-vay.

Some descendants prefer the endonym Kizh, which they argue is an earlier and more historically accurate name that was well documented by records of the Smithsonian Institution, Congress, the Catholic Church, the San Gabriel Mission, and other historical scholars.

Gabrieleño

The Spanish referred to the indigenous peoples surrounding Mission San Gabriel as the Gabrieleño. This was not their autonym, or their name for themselves. Because of historical uses, the term is part of every official tribe's name in this area, spelled either as "Gabrieleño" or "Gabrielino."

History

Before the mission period

Evidence suggests that the Tongva are descended from Uto-Aztecan-speaking peoples who originated in what is now Nevada, and moved southwest into coastal Southern California 3,500 years ago.

In 1811, the priests of Mission San Gabriel recorded at least four languages; Kokomcar, Guiguitamcar, Corbonamga, and Sibanga. During the same time, three languages were recorded in Mission San Fernando.

The Tongva spoke a language of the Uto-Aztecan family (the remote ancestors of the Tongva probably coalesced as a people in the Sonoran Desert, between perhaps 3,000 and 5,000 years ago).

The majority of Tongva territory was located in what has been referred to as the Sonoran life zone, with rich ecological resources of acorn, pine nut, small game, and deer. On the coast, shellfish, sea mammals, and fish were available. Prior to Christianization, the prevailing Tongva worldview was that humans were not the apex of creation, but were rather one strand in the web of life. Humans, along with plants, animals, and the land were in a reciprocal relationship of mutual respect and care, which is evident in their creation stories. The Tongva understand time as nonlinear and there is constant communication with ancestors.

On October 7, 1542, an exploratory expedition led by Spanish explorer Juan Cabrillo reached Santa Catalina in the Channel Islands, where his ships were greeted by Tongva in a canoe. The following day, Cabrillo and his men, the first Europeans known to have interacted with the Gabrieleño people, entered a large bay on the mainland, which they named "Baya de los Fumos" ("Bay of Smokes") on account of the many smoke fires they saw there. This is commonly believed to be San Pedro Bay, near present-day San Pedro.

Colonization and the mission period (1769–1834)

The Gaspar de Portola expedition in 1769 was the first contact by land to reach Tongva territory. Franciscan padre Junipero Serra accompanied Portola. Within two years of the expedition, Serra had founded four missions, including Mission San Gabriel, founded in 1771 and rebuilt in 1774, and Mission San Fernando, founded in 1797.

The people enslaved at San Gabriel were referred to as Gabrieleños, while those enslaved at San Fernando were referred to as Fernandeños.

Entire villages were baptized and indoctrinated into the mission system with devastating results. For example, from 1788 to 1815, natives of the village of Guaspet were baptized at San Gabriel.

There is much evidence of Tongva resistance to the mission system. Many individuals returned to their village at time of death. Traditional foods were incorporated into the mission diet and lithic and shell bead production and use persisted. More overt strategies of resistance such as refusal to enter the system, work slowdowns, and fugitivism were also prevalent. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone.

By the 1800s, San Gabriel was the richest in the entire colonial mission system, supplying cattle, sheep, goats, hogs, horses, mules, and other supplies for settlers and settlements throughout Alta California.

The mission functioned as a slave plantation. Latter-day ethnologist Hugo Reid reported, “Indian children were taken from their parents to be raised behind bars at the mission. They were allowed outside the locked dormitories only to attend to church business and their assigned chores. When they were old enough, boys and girls were put to work in the vast vineyards and orchards owned by the missions. Soldiers watched, ready to hunt down any who tried to escape.” Writing in 1852, Reid said he knew of Tongva who “had an ear lopped off or were branded on the lip for trying to get away.”

In 1810, the "Gabrieleño" labor population at the mission was recorded to be 1,201. It jumped to 1,636 in 1820 and then declined to 1,320 in 1830. Resistance to this system of forced labor continued into the early 19th century. In 1817, the San Gabriel Mission recorded that there were "473 Indian fugitives." In 1828, a German immigrant purchased the land on which the village of Yang-Na stood and evicted the entire community with the help of Mexican officials.

Mexican secularization and occupation (1834–1848)

The mission period ended in 1834 with secularization under Mexican rule. Some "Gabrieleño" absorbed into Mexican society as a result of secularization. Tongva and other California Natives largely became workers while former Spanish elites were granted huge land grants.

Land was systemically denied to California Natives by Californio land owning men. Most Tongva became landless refugees during this period. Entire villages fled inland to escape the invaders and continued devastation. Others moved to Los Angeles, a city which saw an increase in the Native population from 200 in 1820 to 553 in 1836 (out of a total population of 1,088).

Several Gabrieleño families stayed within the San Gabriel township, which became "the cultural and geographic center of the Gabrieleño community." By 1844, most Natives in Los Angeles worked as servants in a perpetual system of servitude, tending to the land and serving settlers, invaders, and colonizers.

In 1847, a law was passed that prohibited Gabrielenos from entering the city without proof of employment. A part of the proclamation read:

Indians who have no masters but are self-sustaining, shall be lodged outside of the City limits in localities widely separated... All vagrant Indians of either sex who have not tried to secure a situation within four days and are found unemployed, shall be put to work on public works or sent to the house of correction.

In 1848, Los Angeles formally became a town of the United States following the Mexican-American War.

American occupation and continued subjugation (1848–)

Landless and unrecognized, the people faced continued violence, subjugation, and enslavement (through convict labor) under American occupation. Some of the people were displaced to small Mexican and Native communities in the Eagle Rock and Highland Park districts of Los Angeles as well as Pauma, Pala, Temecula, Pechanga, and San Jacinto. Imprisonment of Natives in Los Angeles was a symbol of establishing the new "rule of law."

An 1852 editorial in the Los Angeles Star revealed the public's anger towards any possibility of the Gabrieleño receiving recognition and exercising sovereignty.

In 1855, the Gabrieleño were reported by the superintendent of Indian affairs Thomas J. Henley to be in "a miserable and degraded condition." However, Henley admitted that moving them to a reservation, potentially at Sebastian Reserve in Tejon Pass, would be opposed by the citizens because "in the vineyards, especially during the grape season, their labor is made useful and is obtained at a cheap rate." A few Gabrieleño were in fact at Sebastian Reserve and maintained contact with the people living in San Gabriel during this time.

In 1882, Helen Hunt Jackson was sent by the federal government to document the condition of the Mission Indians in southern California. She reported that there were a considerable number of people "in the colonies in the San Gabriel Valley, where they live like gypsies in brush huts, here today, gone tomorrow, eking out a miserable existence by days' work." However, even though Jackson's report would become the impetus for the Mission Indian Relief Act of 1891, the Gabrieleño were "overlooked by the commission charged with setting aside lands for Mission Indians."

Extinction myth

By the early twentieth century, Gabrieleño identity had suffered greatly under American occupation. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican, learned Spanish, and adopted Catholicism while keeping their identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for mentioning that they were "Indian" and many of the people assimilated into Mexican-American or Chicano culture. Further attempts to establish a reservation for the Gabrieleño in 1907 failed. Soon it began to be perpetuated in the local press that the Gabrieleño were extinct. In February 1921, the Los Angeles Times declared that the death of Jose de los Santos Juncos, an Indigenous man who lived at Mission San Gabriel and was 106 years old at his time of passing, "marked the passing of a vanished race." In 1925, Alfred Kroeber declared that the Gabrieleño culture was extinct, stating "they have melted away so completely that we know more of the finer facts of the culture of ruder tribes." Scholars have noted that this extinction myth has proven to be "remarkably resilient," yet is untrue.

Despite being declared extinct, Gabrieleño children were still being assimilated by federal agents who encouraged enrollment at Sherman Indian School in Riverside, California. Between 1890 and 1920, at least 50 Gabrieleño children were recorded at the school. Between 1910 and 1920, the establishment of the Mission Indian Federation, of which the Gabrieleño joined, led to the 1928 California Indians Jurisdictional Act, which created official enrollment records for those who could prove ancestry from a California Indian living in the state in 1852. Over 150 people self-identified as Gabrieleño on this roll. A Gabrieleño woman at Tejon Reservation provided the names and addresses of several Gabrieleño living in San Gabriel, showing that contact between the group at Tejon Reservation and the group at San Gabriel township, which are more than 70 miles apart, was being maintained into the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1971, Bernice Johnston, former curator of the Southwest Museum and author of California’s Gabrieleno Indians (1962), spoke to the Los Angeles Times: “After spending much of her life trying to trace the Indians, she believes she almost came in contact with some Gabrielenos a few years ago…She relates that on a Sunday, while giving a tour of the museum, ‘I saw these shy, dark people looking around. They were asking questions about the Gabrieleno Indians. I asked why they wanted to know, and nearly fell over when they told me they were Gabrielenos and wanted to know something about themselves. I was busy with the tour, we were crowded. I rushed back to them as soon as I could but they were gone. I didn’t even get their names.”

Desecrated sites and Land Back

The continued denigration and denial of tribal identity perpetuated by Anglo-American institutions such as schools and museums has presented numerous obstacles for the people throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Contemporary members have cited being denied the legitimacy of their identity. Tribal identity is also hindered by a lack of federal recognition and having no land base, which has meant that the tribe has access to almost none of their traditional homelands.

The Tongva have also struggled to protect their sacred sites, ancestral remains, and artifacts from destruction in the 21st century. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old Bolsa Chica village site was heavily damaged. The company that performed the initial archaeological survey was fined $600,000 for its poor assessment that clearly favored the developer. Burials near the site of Genga were unearthed and moved, despite opposition from the tribes, in favor of commercial development.

In 2019, CSU, Long Beach dumped trash and dirt on top of Puvunga in its construction of new student housing, which reawakened a decades-long dispute between the university and the tribe over the treatment of the sacred site. In 2022, it was announced that part of the village site of Genga may be transformed into a green space. Leaders of the project have claimed that "tribal descendants of the area’s earliest residents will also have a voice" in how the park is developed.

The Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy has been established as part of the Land Back movement and for rematriation of Tongva homelands. The kuuyam nahwá’a ("guest exchange") has been developed by the conservancy as a way for people living on the homelands of the Tongva to pay a form of contribution for living on the land. In October 2022, a 1-acre site was returned to the conservancy by a private resident in Altadena, which marked the first time the Tongva had land in Los Angeles County in 200 years.

Culture

The Tongva lived in the main part of the most fertile lowland of southern California, including a stretch of sheltered coast with a pleasant climate and abundant food resources, and the most habitable of the Santa Barbara Islands. They have been referred to as the most culturally 'advanced' group south of the Tehachapi, and the wealthiest of the Uto-Aztecan speakers in California, dominating other native groups culturally wherever contacts occurred. Many of the cultural developments of the surrounding southern peoples had their origin with the Gabrieleño. The Tongva territory was the center of a flourishing trade network that extended from the Channel Islands in the west to the Colorado River in the east, allowing the people to maintain trade relations with the Cahuilla, Serrano, Luiseño, Chumash, and Mohave.

Like all Indigenous peoples, they utilized and existed in an interconnected relationship with the flora and fauna of their familial territory. Villages were located throughout four major ecological zones, as noted by biologist Matthew Teutimez: interior mountains and foothills, grassland/oak woodland, sheltered coastal canyons, and the exposed coast. Therefore, resources such as plants, animals, and earth minerals were diverse and used for various purposes, including for food and materials. Prominent flora included oak (Quercus agrifolia) and willow (Salix spp.) trees, chia (Salvia columbariae), cattail (Typha spp.), datura or jimsonweed (Datura innoxia), white sage (Salvia apiana), Juncus spp., Mexican Elderberry (Sambucus), wild tobacco (Nicotiana spp.), and yucca (Hesperoyucca whipplei). Prominent fauna included mule deer, pronghorn, black bear, grizzly bear, black-tailed jackrabbit, cottontail, bald eagle, red-tailed hawk, dolphin, and gray whale.

Te'aat and the ocean

The Tongva had a concentrated population along the coast. They fished and hunted in the estuary of the Los Angeles River, and like the Chumash, their neighbors to the north and west along the Pacific coast, the Gabrieleño built seaworthy plank canoes, called te'aat, from driftwood. To build them, they used planks of driftwood pine that were sewn together with vegetable fiber cord, edge to edge, and then glued with the tar that was available either from the La Brea Tar Pits, or as asphalt that had washed up on shore from offshore oil seeps. The finished vessel was caulked with plant fibers and tar, stained with red ochre, and sealed with pine pitch. The te'aat, as noted by the Sebastián Vizcaíno expedition, could hold up to 20 people as well as their gear and trade goods. These canoes allowed the development of trade between the mainland villages and the offshore islands, and were important to the region's economy and social organization, with trade in food and manufactured goods being carried on between the people on the mainland coast and people in the interior as well. The Gabrieleño regularly paddled their canoes to Catalina Island, where they gathered abalone, which they pried off the rocks with implements made of fragments of whale ribs or other strong bones.

Food culture

In the Tongva economic system, food resources were managed by the village chief, who was given a portion of the yield of each day's hunting, fishing, or gathering to add to the communal food reserves. Individual families stored some food to be used in times of scarcity. Villages were located in places with accessible drinking water, protection from the elements, and productive areas where different ecological niches on the land intersected. Situating their villages at these resource islands enabled the Tongva to gather the plant products of two or more zones in close proximity.

Households consisted of a main house (kiiy) and temporary camp shelters used during food gathering excursions. In the summer, families who lived near grasslands collected roots, seeds, flowers, fruit, and leafy greens, and in the winter families who lived near chaparral shrubland collected nuts and acorns, yucca, and hunted deer. The group used “wooden tongs” to collect prickly pear fruits.

Some prairie communities moved to the coast in the winter to fish, hunt whales and elephant seals, and harvest shellfish. Those villages located on the coast during the summer went on food collecting trips inland during the winter rainy season to gather roots, tubers, corms, and bulbs of plants including cattails, lilies, and wild onions.

The Tongva did not practice horticulture or agriculture, as their well-developed hunter-gatherer and trade economy provided adequate food resources. Bread was made from the yellow pollen of cattail heads, and the underground rhizomes were dried and ground into a starchy meal. The young shoots were eaten raw. The seeds of chia, a herbaceous plant of the sage family, were gathered in large quantities when they were ripe. The flower heads were beaten with a paddle over a tightly woven basket to collect the seeds. These were dried or roasted and ground into a flour called "pinole," which was often mixed with the flour of other ground seeds or grains. Water was added to make a cooling drink; mixing with less water yielded a kind of porridge that could be baked into cakes.

Acorn mush was a staple food as it was of all the Indigenous peoples who were forcibly relocated to missions in Southern California. Acorns were gathered in October; this was a communal effort with the men climbing the trees and shaking them while the women and children collected the nuts. The acorns were stored in large wicker granaries supported by wooden stakes well above the ground. Preparing them for food took about a week. Acorns were placed, one at a time, on end in the slight hollow of a rock and their shells broken by a light blow from a small hammerstone; then the membrane, or skin, covering the acorn meat was removed. Following this process the acorn meats were dried for days, after which the kernels were pounded into meal with a pestle. This was done in a stone mortar or in a mortar hole in a boulder. Large bedrock outcroppings near oak stands often display evidence of the community mills where the women labored.

The pounded acorn meal was put into baskets and the bitter tannic acid it contained was leached out to make the meal more palatable and digestible. The prepared meal was cooked by boiling in water in a watertight grass-woven basket or in a soapstone bowl into which heated stones were dropped. Soapstone casseroles were used directly over the fire. Various foods of meat, seeds, or roots were cooked by the same method. The mush thus prepared was eaten cold or nearly so, as was all their food. Another favored Tongva food was the seed kernel of a species of plum (prunus ilicifolia, aka holly-leaf cherry) they called islay, which was ground into meal and made into gruel.

Men performed most of the heavy, short-duration labor; they hunted, fished, helped with some food-gathering, and carried on trade with other cultural groups. Large game animals were hunted with bow and arrows, and small game was taken with deadfall traps, snares, and bows made of buckeye wood. John P. Harrington recorded that rattlesnake venom was used as an arrow poison. Burrowing animals were driven from their burrows with smoke and clubbed; communal rabbit drives were made during the seasonal controlled burning of chaparral on the prairie, the rabbits being killed with nets, bow and arrows, and throwing sticks.

Harpoons, spear-throwers, and clubs were used to hunt marine mammals and te'aat used to access them. Fishing was done from shorelines or along rivers, streams, and creeks with hook and line, nets, basketry traps, spears, bow and arrows, and poisons made from plants. Reciprocity and sharing of resources were important values in Tongva culture. Hugo Reid reported that the hoarding of food supplies was so stigmatized by the Tongva moral code that hunters would give away large portions of coveted foods such as fresh meat, and under some circumstances, were prohibited from eating their own kill or fishermen from eating their own catch.

Women collected and prepared plant and some animal food resources and made baskets, pots, and clothing. In their old age, they and the old men cared for the young and taught them Tongva lifeways.

Material culture

Tongva material culture and technology reflected a sophisticated knowledge of the working properties of natural materials and a highly developed artisanship, shown in many articles of everyday utility decorated with shell inlay, carving, and painting. Most of these items, including baskets, shell tools, and wooden weapons, were extremely perishable. Soapstone from quarries on Catalina Island was used to make cooking implements, animal carvings, pipes, ritual objects, and ornaments.

Using the stems of rushes (Juncus sp .), grass (Muhlenbergia rigens), and squawbush (Rhus trilobata), women fabricated coiled and twined basketry in a three-color pattern for household use, seed collecting, and ceremonial containers to hold grave offerings. They sealed some baskets, such as water bottles, with asphalt to make watertight containers for holding liquids.

The Tongva used the leaves of tule reeds as well as those of cattails to weave mats and thatch their shelters.

Living in the mild climate of southern California, the men and children usually went nude, and women wore only a two-piece skirt, the back part being made from the flexible inner bark of cottonwood or willow, or occasionally deerskin. The front apron was made of cords of twisted dog bane or milkweed. People went barefoot except in rough areas where they wore crude sandals made of yucca fiber. In cold weather, they wore robes or capes made from twisted strips of rabbit fur, deer skins, or bird skins with the feathers still attached. Also used as blankets at night, these were made of sea otter skins along the coast and on the islands. “Women were tattooed from cheek to shoulder blade, from elbow to shoulder,” with cactus thorns used as needles and charcoal dust rubbed into the wounds as “ink,” leaving a blue-gray mark under the skin after the wounds healed.

Social culture

According to Father Gerónimo Boscana, relations between the Chumash, Gabrieleños, Luiseños, and Diegueños, as he called them, were generally peaceful but “when there was a war it was ferocious…no quarter was given, and no prisoners were taken except the wounded.”

Contemporary tribe

The earliest ethnological surveys of the Christianized population of the San Gabriel area, who were then known by the Spanish as Gabrielino, were conducted in the mid-19th century. By this time, their pre-Christian religious beliefs and mythology were already fading. The Gabrieleño language was on the brink of extinction by 1900, so only fragmentary records of the indigenous language and culture of the Gabrieleño have been preserved. Gabrieleño was one of the Cupan languages in the Takic language group, which is part of the Uto-Aztecan family of languages. It may be considered a dialect with Fernandeño, but it has not been a language of everyday conversation since the 1940s. The Gabrieleño people now speak English but a few are attempting to revive their language by using it in everyday conversation and ceremonial contexts. Presently, Gabrieleño is also being used in language revitalization classes and in some public discussion regarding religious and environmental issues.

The library of Loyola Marymount University, located in Los Angeles (Westchester), has an extensive collection of archival materials related to the Tongva and their history.

In the 21st century, an estimated 1,700 people self-identify as members of the Tongva or Gabrieleño tribe. In 1994, the state of California recognized the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe (Spanish: Tribu de Gabrieleño-Tongva) and the Fernandino-Tongva Tribe (Spanish: Tribu de Fernandeño-Tongva), but neither has gained federal recognition. In 2013, it was reported that the four Tongva groups that have applied for federal recognition had over 3,900 members collectively.

The Gabrieleño/Tongva people do not accept one organization or government as representing them. They have had strong internal disagreements about governance and their future, largely related to plans supported by some members to open a gaming casino on land that would be considered part of the Gabrieleño/Tongva's homeland. Gaming casinos have generated great revenues for many Native American tribes, but not all Tongva people believe the benefits outweigh negative aspects. The Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe (sometimes called the "slash" group) and Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe (sometimes called the "hyphen" group) are the two primary factions advocating a casino for the Tongva nation, with sharing of revenues by all the people. The Gabrielino Tribal Council of San Gabriel, now known as the Kizh Nation (Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians), claims that it does not support gaming. The Gabrieleno Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians also does not support gambling and has been operating and meeting in the city of San Gabriel for over a hundred years. None of these organizations is recognized as a tribe by the federal government.

History of organizations and casino dispute

In 1990, the Gabrielino/Tongva of San Gabriel filed for federal recognition. Other Gabrieleño groups have done the same. The Gabrielino/Tongva of California Tribal Council and the Coastal Gabrielino-Diegueno Band of Mission Indians filed federal petitions in 1997. These applications for federal recognition remain pending.

The San Gabriel group gained acknowledgement of its nonprofit status by the state of California in 1994. In 2001, the San Gabriel council divided over concessions given to the developers of Playa Vista and a proposal to build an Indian casino in Compton, California. A Santa Monica faction formed that advocated gaming for the tribe, which the San Gabriel faction opposed.

The San Gabriel council and Santa Monica faction sued each other over allegations that the San Gabriel faction expelled some members in order to increase gaming shares for other members. There were allegations that the Santa Monica faction stole tribal records in order to support its case for federal recognition.

In September 2006, the Santa Monica faction divided into the "slash" and "hyphen" groups: the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe and Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe. Tribal secretary Sam Dunlap and tribal attorney Jonathan Stein confronted each other over various alleged fiscal improprieties and derogatory comments made to each other. Since that time, the slash group has hired former state senator Richard Polanco as its chief executive officer. The hyphen group has allied with Stein and issued warrants for the arrest of Polanco and members of the slash group.

Stein's group (hyphen), the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe, is based in Santa Monica. It has proposed a casino to be built in Garden Grove, California, approximately two miles south of Disneyland. In September 2007, the city council of Garden Grove unanimously rejected the casino proposal, instead choosing to build a water park on the land.

Land use issues

Controversies have arisen in contemporary California related to land-use issues and Native American rights, including those of the Tongva. Since the late twentieth century, both the state and the United States governments have improved respect of indigenous rights and tribal sovereignty. The Tongva have challenged local development plans in the courts in order to protect and preserve some of their sacred grounds. Given the long indigenous history in the area, not all archeological sites have been identified.

Sometimes land developers have inadvertently disturbed Tongva burial grounds. The tribe denounced archeologists breaking bones of ancestral remains found during an excavation of a site at Playa Vista. An important resolution was finally honored at the Playa Vista project site against the 'Westchester Bluffs' near the Ballona Wetlands estuary and by the historic natural course of Ballona Creek.

In the 1990s, the Gabrielino/Tongva Springs Foundation revived use of the Kuruvungna Springs for sacred ceremonies. The natural springs are located on the site of a former Tongva village, now developed as the campus of University High School in West Los Angeles. The Tongva consider the springs, which flow at 22,000 gallons per day, to be one of their last remaining sacred sites and they regularly make them the centerpiece of ceremonial events.

The Tongva have another sacred area known as Puvungna. They have believed it is the birthplace of the Tongva prophet Chingishnish, and many believe it to be the place of creation. The site contains an active spring and the area was formerly inhabited by a Tongva village. It has been developed as part of the grounds of California State University, Long Beach. A portion of Puvungna, a Tongva burial ground on the western edge of the campus, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In October 2019, following the dumping of soil, along with concrete, rebar and other debris, on "land that holds archeological artifacts actively used by local Tribal groups for ceremonies" from a nearby construction site, the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation–Belardes, and the California Cultural Resource Preservation Alliance (CCRPA) filed a lawsuit against the university. In November 2019, the university agreed to stop dumping materials onto the site, and as of 2020 the lawsuit between these parties is still ongoing.

Traditional narratives

Tongva/Gabrieleño/Fernandeño oral literature is relatively little known, due to their early Christianization in the 1770s by Spanish missions in California. The available evidence suggests strong cultural links with the group's linguistic kin and neighbors to the south and east, the Luiseño and the Cahuilla.

According to Kroeber (1925), the pre-Christian Tongva had a "mythic-ritual-social six-god pantheon". The principal deity was Chinigchinix, also known as Quaoar. Another important figure is Weywot, the god of the sky, who was created by Quaoar. Weywot ruled over the Tongva, but he was very cruel, and he was finally killed by his own sons. When the Tongva assembled to decide what to do next, they had a vision of a ghostly being who called himself Quaoar, who said he had come to restore order and to give laws to the people. After he had given instructions as to which groups would have political and spiritual leadership, he began to dance and slowly ascended into heaven.

After consulting with the Tongva, astronomers Michael E. Brown and Chad Trujillo used the name of Quaoar to name a large object in the Kuiper belt that they had discovered, 50000 Quaoar (2002). When Brown later found a satellite of Quaoar, he left the choice of name up to the Tongva, who selected Weywot (2009).

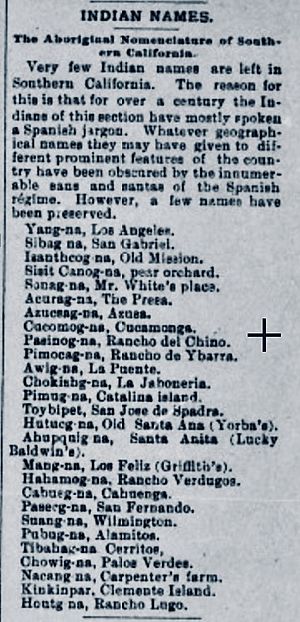

Toponymy

From the Spanish colonial period, Tongva place names have been absorbed into general use in Southern California. Examples include Pacoima, Tujunga, Topanga, Rancho Cucamonga, Azusa (Azucsagna), and Cahuenga Pass.

Sacred sites that have not been totally demolished, destroyed, or built over include Puvunga, Kuruvungna Springs, and Eagle Rock.

In other cases, toponyms or places have been recently named to honor the indigenous peoples. The Gabrielino Trail is a 28-mile path through the Angeles National Forest, created and named in 1970.

A 2,656-foot summit in the Verdugo Mountains, in Glendale, was named Tongva Peak in 2002, following a proposal by Richard Toyon.

Tongva Park is a 6.2-acre park in Santa Monica, California. The park is located just south of Colorado Avenue, between Ocean Avenue and Main Street. The park includes an amphitheater, playground, garden, fountains, picnic areas, and restrooms. The park was dedicated on October 13, 2013.

Notable Tongva

- Chief Vera Ya'anna Rocha, late chairwoman and tribal leader of the Gabrielino-Shoshone Tribal Nation. Rocha is credited as a pioneer in modern Gabrielino movements, such as environmental protections for sacred areas including the Ballona Wetlands and the Etiwanda Sage Preservation.

- Chief Red Blood Anthony Morales, chairman and tribal leader of the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation. In 2008, he received the "Heritage Award" from the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California

- Jimi Castillo, Gabrielino/Tongva Elder, Pipe Carrier, and member of the State-Wide Bear Clan. In 2016, Jimi received the Heritage Award from the Aquarium of the Pacific, and the Volunteer Lifetime Achievement Award from the Obama White House for his work in the Native Community. He is also known for his work in prisons.

- Tonantzin Carmelo, actress

- L. Frank, artist, author, indigenous language activist.

- Nicolás José, led two late-eighteenth century revolts against the Spanish colonizers in 1779 and 1785 in collaboration with Toypurina.

- Victoria Reid (~1809–1868) was a woman from the village of Comicranga who became a respected landowner in Mexican California, before experiencing a decline in status in white American society. She was married to Hugo Reid.

- Reginald "Reggie" Rodriguez, (1948–1969) a Vietnam War hero. Reggie Rodriguez Park in Montebello, California, is named in his honor and is an 11-acre (4.5 ha) area on which the Reggie Rodriguez Community Center is located, noted for its unique architecture and providing a central location for activities for the at-risk youth population in the city. Reginald was a direct descendant of the San Gabriel Mission Indians (Tongva) with family buried on mission grounds.

- Toypurina (1760–1799) was a Gabrieliño medicine woman who opposed the rule of colonization by Spanish missionaries in California, and led an unsuccessful rebellion against them in 1785.

- Charles Sepulveda – professor and author

- Julia Bogany (1948–2021), educator, cultural consultant

- Cindy Alvitre, former tribal leader, educator, cultural consultant

- Weshoyot Alvitre, comic book artist and illustrator

- Emilio Reyes, researcher and genealogist

See also

In Spanish: Tongva para niños

In Spanish: Tongva para niños