Jack Charles facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jack Charles

|

|

|---|---|

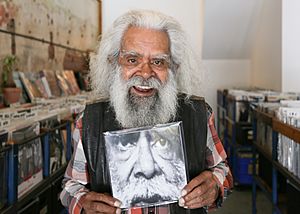

Charles holding his record in 2019

|

|

| Born | 5 September 1943 Carlton, Victoria, Australia

|

| Died | 13 September 2022 (aged 79) Parkville, Victoria, Australia

|

| Other names | Uncle Jack Charles |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1970–2022 |

Jack Charles (5 September 1943 – 13 September 2022), also known as Uncle Jack Charles, was an Australian stage and screen actor and activist, known for his advocacy for Aboriginal people. He was involved in establishing the first Indigenous theatre in Australia, co-founding Nindethana Theatre with Bob Maza in Melbourne in 1971. His film credits include the Australian film The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), among others, and more recently appeared in TV series Cleverman (2016) and Preppers (2021).

He spent many decades in and out of prison, which he ascribed largely to trauma that he experienced as a child, as one of the Stolen Generations. In later life he became a mentor for Aboriginal youth in the prison system along with musician Archie Roach, and was revered as an elder. As a gay man, Charles was considered a gay icon and role model for LGBTQI+ Indigenous youth.

Among other awards and honours, he was Victorian Senior Australian of the Year in 2015, and Male Elder of the Year in the 2022 National NAIDOC Week Awards.

Contents

Early life

Jack Charles was born on 5 September 1943 at the Royal Women's Hospital, Carlton, in Melbourne, Victoria, to a Bunurong mother, Blanche, who was 15 years old at the time, and Wiradjuri father. Charles' great-great-grandfather was a Djadjawurrung man, among the activists who resisted government policy at the Coranderrk reserve in Victoria in 1881.

Charles was a victim of the Australian Government's forced assimilation program which took him from his mother as an infant, and which produced what is known as the Stolen Generations. He tells how his mother sneaked out of the Royal Women's Hospital and took him to a "blakfella camp" near Shepparton and Mooroopna (Daish's Paddock), but the authorities came and took him when he was four months old.

After being moved to the Melbourne City Mission in Brunswick, Charles was raised in the Salvation Army Boys' Home at Box Hill, suburban Melbourne, where he was the only Aboriginal child. He was not told that he was Aboriginal, and thought he was an orphan until he later discovered the existence of his still living mother. At the age of 14, he was taken into the care of a foster mother, Mrs Murphy, who treated him well, but was taken away again at the age of 17, after he dipped into his pay packet to pay for a trip to see his mother, whom he had heard was in Swan Hill (although he did not get to see her that time) and had an altercation with Mrs Murphy. He connected with some other siblings when still a teenager, and later learned more about his birth family and ancestors.

Acting career

Theatre

In 1970, Charles started his acting career in theatre. First, he was invited by members of the New Theatre in Melbourne to audition for a production of A Raisin in the Sun, a play written by the African-American playwright Lorraine Hansberry. The director of the New Theatre, Dot Thompson, cast Charles in South African playwright Athol Fugard's The Blood Knot, which was performed in 1970. This was followed by a non-Aboriginal role in Rod Milgate's A Refined Look at Existence. He later said that the New Theatre, with whom he spent seven years, was his NIDA (National Institute of Dramatic Art), as well as like family to him.

Charles was involved in establishing Indigenous theatre in Australia. In 1971, he co-founded, with Bob Maza, Nindethana ("place for a corroboree") at The Pram Factory in Melbourne, Australia's first Indigenous theatre group. Their first hit play, in 1972, was called Jack Charles is Up and Fighting, and included music composed by him. He is often referred to as "the grandfather of Indigenous theatre" because of this early work. He also helped to develop the National Black Theatre in Redfern, Sydney.

In August 1972, Charles played a character based on his own, in a one-act play for four actors, written by John Romeril. The play was performed at the Pram Factory and directed by Bruce Spence.

In 1974, Charles played Bennelong in the Old Tote Theatre production of Michael Boddy's Cradle of Hercules, which was presented at the Sydney Opera House as part of its opening season. Also in the cast was a young David Gulpilil.

His stage work includes Jack Davis' play No Sugar for the Black Swan Theatre Company in Perth, Western Australia.

In 2010, Ilbijerri Theatre staged Charles' one-man show called Jack Charles v The Crown at the Melbourne Festival. Bob Maza's daughter, Rachael Maza, as artistic director of Ilbijerri, was involved in the production, and playwright John Romeril co-wrote the script. In the show, Charles talks about his life, including his removal from his family and its consequences, and his crimes. It also charts his attempts to navigate red tape to work in prisons as a mentor for Aboriginal inmates. Charles was nominated for a Helpmann Award for Best Male Actor in a Play for his performance in the play, which toured across Australia and internationally, including Japan, Canada, Britain and the United States, for ten years. In 2014, Ilbijerri Theatre, toured by Performing Lines, won the Helpmann Award for Best Regional Touring Production, and in the same year Ilbijerri was joint winner of a Drover Award from APACA.

In 2012, Charles performed in the Sydney Festival production I am Eora.

In August 2014, Charles performed in Ilbijerri Theatre and Belvoir Theatre's Coranderrk at Northcote Town Hall.

Film and TV

In 1972, Charles auditioned for the role of the Australian Indigenous title character in the television show Boney but was declined. The job went to New Zealand-born white actor James Laurenson, who wore brown face make-up for the role. It was partly due to this disappointment, that the white establishment was not yet ready to accept Aboriginal actors in major roles, that led to his co-founding of Nindethana and the development of black theatre for Indigenous people.

Charles was the subject of Amiel Courtin-Wilson's documentary film, Bastardy, which followed him for seven years. The film was in the official selection for Singapore, Melbourne (MIFF), Sydney, Sheffield Doc/Fest, and others, and was nominated for numerous awards. The film won the Film Critics Circle of Australia Award for Best Documentary in 2009; Best Documentary Human Story at the 2009 ATOM Awards; and the Grand Jury Prize at the FIFO International Documentary Film Festival in 2010. The film was re-screened at MIFF in 2017, with Charles on the night crediting the film with having saved his life. The film brought affection from strangers who had seen the film, and it resuscitated his career as an actor.

He played Chief Great Little Panther in Joe Wright's 2015 fantasy film Pan.

Charles appeared in several episodes of the sketch comedy show, Black Comedy, between 2014 and 2020, his final role being that of a judge.

In 2016, Charles appeared in two episodes of the television horror drama series Wolf Creek. Also in 2016, he appeared in the television drama series Cleverman. Charles appeared in the 2021 television comedy series Preppers.

Radio

Charles was interviewed on ABC Radio many times over the years, by Larissa Behrendt, Daniel Browning, Richard Fidler on Conversations, among others.

Jail

For a large part of his life, Charles was a petty thief. He was jailed 22 times.

Other activities and later life

He developed an interest in pottery in prison in Castlemaine in the 1970s, and after developing his skills he taught other prisoners in what was a successful program. He enjoyed creating works through his lifetime, finding the practice meditative.

Charles received a Christian education from the Salvation Army, and continued to observe Christian values into his 70s.

He liked to believe that Bundjil, the great wedge-tailed eagle, the ancestor spirit and creator of the Kulin land and its people, that had kept him alive through his darkest and riskiest moments in his life.

In later life he became somewhat of a role model for young Indigenous men fighting institutionalised racism, and lacking a connection to culture, and, after being eventually allowed into the prison system, mentored Aboriginal prison inmates in Victorian prisons and youth detention centres. He also advocated for more Indigenous community centres in regional centres such as Horsham or Shepparton, for young people to gather in "a sanctuary for Aboriginal people where the community can get together and talk about our personal issues with each other...". He said that he had petitioned local councils and later the Victorian Minister for Aboriginal Affairs to create a community centre for people after their release from prison, but had not been listened to. The story of his efforts was told in the show Jack Charles v The Crown (2010).

In 2017, Charles gave a talk about his passion for prison mentoring at TEDx in Sydney, and his work with Uncle Archie Roach at the Archie Roach Foundation, followed by a performance of Roach's song "We Won't Cry" by the two of them. The two men worked in prisons mentoring Aboriginal prisoners through Roach's foundation.

In 2019, Charles embarked on a speaking tour in a series of events called A Night with Jack Charles, in which he talked about his life as a gay Indigenous man, describing it later as "the story of a reformed and rehabilitated old coot that [the audience] feel they know so well. They've seen me at my worst, read about me at my worst, and now they see me at my best."

Charles' memoir, authored by Namila Benson, Jack Charles: Born-Again Blakfella, was published on 18 August 2020 by Penguin. The memoir was shortlisted by the Australian Book Industry Awards for the 2020 Biography Book of the Year.

In April 2021, Charles was the first Aboriginal elder to speak at the Victorian truth-telling commission, the Yoorrook Justice Commission, which aims to establish an official public record of the experience of Aboriginal Victorians since the start of British colonisation in Victoria. Its findings, scheduled to be reported by June 2024, will inform Victoria's Treaty negotiations.

Death and legacy

In later life, Charles was often referred to as Uncle Jack or Uncle Jack Charles, a mark of respect that often goes with the status of an Aboriginal Australian elder. He is remembered as "the grandfather of Indigenous theatre" because of this early work.

Charles died from a stroke on 13 September 2022 at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, eight days after his 79th birthday, and was given a farewell by his family with a smoking ceremony. His death was widely reported in the Australian and international press, with prime minister of Australia Anthony Albanese, musician and comic Adam Briggs, actor Meyne Wyatt, and Aboriginal senator Lidia Thorpe tweeting their respects, and Albanese giving an oral tribute, saying that he left a "joyous legacy" and that Australia had "lost a legend of Australian theatre, film and creative arts".

There was a state memorial for Charles, provided by the Victorian government at Hamer Hall in Melbourne, held on 18 October 2022. It was live-streamed into prisons, remand centres and youth justice centres across Victoria. Hundreds of mourners attended, and crowds gathered outside. Many speakers described Charles' legacy as giving back to the community, after enduring an extraordinarily hard life. Premier Daniel Andrews was unable to attend owing to the flood emergency, with Acting Aboriginal Affairs Minister Colin Brooks addressing the funeral instead. Others to address the funeral included theatre director Rachael Maza and film director Amiel Courtin-Wilson, both friends of Charles. There were stage performances inside and dancers outside.

Recognition, awards and honours

Charles was the subject of Amiel Courtin-Wilson's 2008 documentary Bastardy.

A photograph of Charles taken by in Rod McNicol in 2011 hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of Australia. It won the National Photographic Portrait Prize in 2012. McNicol had met Charles in the early 1970s and created several portraits of him over the years.

A portrait of Charles by Anh Do was the People's Choice Award winner in the 2017 Archibald Prize.

Awards and honours include:

- 2009: Tudawali Award at the Message Sticks Festival, for his lifetime contribution to Indigenous media

- 2014: Lifetime Achievement award from Victoria's Green Room Awards; the first Indigenous recipient

- 2015: Named Victorian Senior Australian of the Year by the Victorian Government

- 2019: Red Ochre Award, a lifetime achievement award given by the Australia Council

- 2022: Male Elder of the Year, National NAIDOC Week Awards

Birth family and personal life

Charles' five times great-grandfather was Mannalargenna, who was a highly respected Aboriginal Tasmanian elder and leader, acting as emissary to surrounding clans in Tasmania. His four times great-grandmother, Woretemoeteyenner (1797–1847), was a strong Aboriginal Tasmanian woman who stood up to the sealers who decimated the population of seals that they relied on for food. His grandmother, Annie Johnson, was an important person in the history of the Murray River region of Victoria. She was known for using her horse and dray for taking food to families when flu epidemics hit the local Aboriginal communities.

Charles met his sisters, Esmae and Eva Jo Charles, as a teenager, when he was living with his foster mother, and they visited him in prison in the 1980s. They managed to find another sister, Christine Zenip Charles, whose foster mother was one of the few who let her keep her Aboriginal name on her birth certificate. He met his mother in Swan Hill when he was 19. By August 2021, Esmae and Eva Jo had died, and there were six siblings still missing.

He only found out who his father was in 2021, when participating in an episode of the SBS Television program Who Do You Think You Are? Hilton Hamilton Walsh was a Wiradjuri man, also known as an Indigenous mentor.

Charles had a relationship with Jack Huston, a "De La Salle College boy", whom he met at the New Theatre in the 1970s, for five years. He credits Jack, who also helped him and Maza and John Smythe establish Nindethana, with helping him to develop an appreciation for ballet, opera and musicals.

Since that early relationship, he chose to remain single (in his words "a loner").

Selected filmography

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith | Harry Edwards | |

| 1993 | Bedevil | Rick | |

| 1993 | Blackfellas | Carey | |

| 2004 | Tom White | Harry | |

| 2008 | Bastardy | Self | Documentary; filmed over 6 years of his life |

| 2013 | Mystery Road | "Old Boy" | |

| 2014 | The Gods of Wheat Street | Old Uncle | TV series; 5 episodes |

| 2015 | Pan | Chief | |

| 2016 | Wolf Creek | Uncle Paddy | TV series; 2 episodes |

| 2016– 2017 |

Cleverman | Uncle Jimmy | TV series; 3 episodes |

| 2018 | Grace Beside Me | Uncle Lefty | TV series; 1 episode ("Catch Your Death") |

| 2019 | True History of the Kelly Gang | Waiter | |

| 2021 | Back to the Outback | Frilled-Neck Lizard | Voice |

| 2021 | Preppers | Monty | TV series; 6 episodes |