Seal hunting facts for kids

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. Seal hunting is currently practiced in ten countries: United States (above the Arctic Circle in Alaska), Canada, Namibia, Denmark (in self-governing Greenland only), Iceland, Norway, Russia, Finland and Sweden. Most of the world's seal hunting takes place in Canada and Greenland.

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) regulates the seal hunt in Canada. It sets quotas (total allowable catch – TAC), monitors the hunt, studies the seal population, works with the Canadian Sealers' Association to train sealers on new regulations, and promotes sealing through its website and spokespeople. The DFO set harvest quotas of over 90,000 seals in 2007; 275,000 in 2008; 280,000 in 2009; and 330,000 in 2010. The actual kills in recent years have been less than the quotas: 82,800 in 2007; 217,800 in 2008; 72,400 in 2009; and 67,000 in 2010. In 2007, Norway claimed that 29,000 harp seals were killed, Russia claimed that 5,479 seals were killed and Greenland claimed that 90,000 seals were killed in their respective seal hunts.

Harp seal populations in the northwest Atlantic declined to approximately 2 million in the late 1960s as a result of Canada's annual kill rates, which averaged to over 291,000 from 1952 to 1970. Conservationists demanded reduced rates of killing and stronger regulations to avert the extinction of the harp seal. In 1971, the Canadian government responded by instituting a quota system. The system was competitive, with each boat catching as many seals as it could before the hunt closed, which the Department of Fisheries and Oceans did when they knew that year's quota had been reached. Because it was thought that the competitive element might cause sealers to cut corners, new regulations were introduced that limited the catch to 400 seals per day, and 2000 per boat total. A 2007 population survey conducted by the DFO estimated the population at 5.5 million.

In Greenland, hunting is done with a firearm (rifle or shotgun) and young are fully protected. This has caused some conflicts with other seal-hunting nations, as Greenland also was hit by the boycotts that often were aimed at seals (often young) killed by clubbing or similar methods, which have not been in use in Greenland. It is illegal in Canada to hunt newborn harp seals (whitecoats) and young hooded seals (bluebacks). When the seal pups begin to molt their downy white fur at the age of 12–14 days, they are called "ragged-jacket" and can be commercially hunted. After molting, the seals are called "beaters", named for the way they beat the water with their flippers. The hunt remains highly controversial, attracting significant media coverage and protests each year. Images from past hunts have become iconic symbols for conservation, animal welfare, and animal rights advocates. In 2009, Russia banned the hunting of harp seals less than one year old.

History

The term seal is used to refer to a diverse group of animals. In science, they are grouped together in the Pinnipeds, which also includes the walrus, not popularly thought of as a seal, and not considered here. The two main families of seals are the Otariidae (the eared seals; includes sea lions, and fur seals), and Phocidae (the earless seals); animals in the family Phocidae are sometimes referred to as hair seals, and are much more adept in the water than the eared seals, though they have a more difficult time getting around on land. The fur seal yields a valuable fur; the hair seal has no fur, but oil can be obtained from its fat and leather from its hide. Seals have been used for their pelts, their flesh, and their fat, which was often used as lamp fuel, lubricants, cooking oil, a constituent of soap, the liquid base for red ochre paint, and for processing materials such as leather and jute.

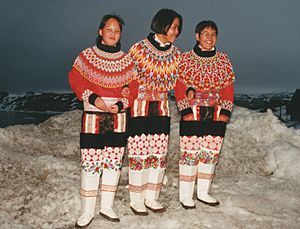

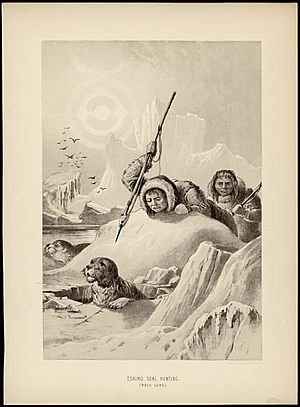

Traditional seal hunting

Archeological evidence indicates the Native Americans and First Nations People in Canada have been hunting seals for at least 4,000 years. Traditionally, when an Inuit boy killed his first seal or caribou, a feast was held. The meat was an important source of fat, protein, vitamin A, vitamin B12 and iron, and the pelts were prized for their warmth. The Inuit diet is rich in fish, whale, and seal.

There were approximately 150,000 circumpolar Inuit in 2005 in Greenland, Alaska, Russia, and Canada. According to Kirt Ejesiak, former secretary and chief of staff to then-Premier of Nunavut, Paul Okalik and the first Inuk from Nunavut to attend Harvard, for the c. 46,000 Canadian Inuit, the seal was not "just a source of cash through fur sales, but the keystone of their culture. Although Inuit harvest and hunt many species that inhabit the desert tundra and ice platforms, the seal is their mainstay. The Inuktitut vocabulary designates specific objects made from seal bone, sinew, fat and fur used as tools, games, thread, cords, fuel, clothing, boats, and tents. There are also words referring to seasons, topography, place names, legends, and kinship relationships based on the seal. One region of Canada's north is inhabited by the Netsilingmiut, or "people of the seal." The title of Ejesiak's article acknowledged the pivotal 1991 publication entitled Animal Rights, Human Rights by George Wenzel, a McGill University geographer and anthropologist who worked more than two decades with the Clyde Inuit of Baffin Island. Wenzel's "scholarly examination" of "the impact of the animal rights movement upon the culture and economy of the Canadian Inuit" was among the first to reveal how animal rights groups, "well-meaning people in the dominant society through misunderstanding and ignorance can inflict destruction" on a vulnerable minority.

Inuit seal hunting accounts for the majority of the seal hunt, but just three percent of the hunt in southern Canada; it is excluded from the European Commission's call in 2006 for a ban on the import, export and sale of all harp and hooded seal products. Ringed seals were once the main staple for food, and have been used for clothing, boots, fuel for lamps, as delicacy, containers, igloo windows, and in harnesses for huskies. Though no longer used to this extent, ringed seals are still an important food and clothing source for the people of Nunavut. Called nayiq by the Central Alaskan Yup'ik people, the ringed seal is also hunted and eaten in Alaska.

Various seal species were also hunted in northwest Europe and the Baltic Sea at least 8,000 years ago.

Early modern era

The first commercial hunting of seals by Europeans, is said to have occurred in 1515, when a cargo of fur seal skins from Uruguay was sent to Spain for sale in the markets of Seville.

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador and the Gulf of St. Lawrence were the first regions to experience large scale sealing. Migratory fishermen began the hunting from as early as the 1500s. Large-scale commercial seal hunting became an annual event starting in 1723 and expanded rapidly near the turn of the 18th century. Initially, the method used was to ensnare the migrating seals in nets anchored to shore installations, known as the 'landsman seal fishery'. The hunt was mainly for the procurement of seal meat as a form of sustenance for the settlements in the area, rather than for commercial gain.

From the early 18th century English hunters began to range further afield – 1723 marked the first time that hunters armed with firearms ventured forth in boats to increase their haul. This soon became a sophisticated commercial operation; the seals were transported back to England, where the seal's meat, fur, and oil were sold separately. From 1749, the import of seal oil to England was being recorded annually, and was used as lighting oil, for cooking, in the manufacture of soap and for the treating of leather.

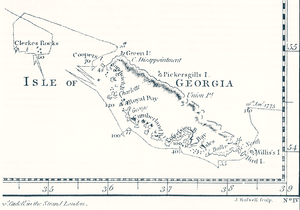

South Atlantic

It was in the South Seas that sealing became a major enterprise from the late 18th century. Samuel Enderby, along with Alexander Champion and John St Barbe organized the first commercial expedition to the South Atlantic Ocean in 1776, initially with the primary aim of whaling, although sealing began to play a prominent part in the operation as well. More expeditions were sent in 1777 and 1778 before political and economic troubles hampered the trade for some time.

On 1 September 1788, the 270-ton ship Emilia, owned by Samuel Enderby & Sons and commanded by Captain James Shields, departed London. The ship went west around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean to become the first ship of any nation to conduct operations in the Southern Ocean. Emilia returned to London on 12 March 1790 with a cargo of 139 tons of sperm oil.

By 1784, the British had fifteen ships in the southern fishery, all from London. By 1790 this port alone had sixty vessels employed in the trade. Between 1793 and 1799 there was an average of sixty vessels in the trade. The average increased to seventy-two in the years between 1800 and 1809.

The sealing industry extended further south to the South Georgia island, first mapped by Captain James Cook in HMS Resolution on 17 January 1775. During the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, South Georgia was inhabited by English and Yankee sealers, who used to live there for considerable periods of time and sometimes overwintered. In 1778, English sealers brought back from the Island of South Georgia and the Magellan Strait area as many as 40,000 seal skins and 2,800 tons of elephant seal oil. More fur seals from the island were taken in 1786 by the English sealing vessel Lord Hawkesbury, and by 1791, 102 vessels, manned by 3000 sealers, were hunting seals south of the equator. The first commercial visit to the South Sandwich Islands was made in 1816 by another English ship, the Ann.

The sealers pursued their trade in a most unsustainable manner, promptly reducing the fur seal population to near extermination. As a result, sealing activities on South Georgia had three marked peaks in 1786–1802, 1814–23, and 1869–1913 respectively, decreasing in between and gradually shifting to elephant seals taken for oil.

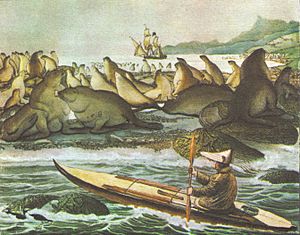

Pacific

Commercial sealing in the Australasian region appears to have started with the London-based Massachusetts-born Eber Bunker, master of the William and Ann, who in November 1791 announced his intention to visit and hunt in New Zealand's Dusky Sound. Captain William Raven of the Britannia stationed a party at Dusky from 1792 to 1793, but the discovery in 1798-1799 of Bass Strait, between mainland Australia and Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) saw the sealers' focus shift there in 1798, when a gang including Daniel Cooper landed from the Nautilus on Cape Barren Island.

With Bass Strait over-exploited by 1802, commercial attention returned to southern New Zealand waters, where Stewart Island/Rakiura and Foveaux Strait were explored, exploited and charted from 1803 to 1804. Thereafter, the sealing-industry focus shifted to the sub-Antarctic Antipodes Islands, 1805–1807, the Auckland Islands from 1806, the southeast coast of New Zealand's South Island, Otago Harbour and Solander Island by 1809, before focusing further to the south at the newly-discovered Campbell Island (discovered in January 1810) and Macquarie Island (discovered in July 1810) from 1810. During this period sealers were active on the southern coast of mainland Australia, for example at Kangaroo Island. This whole development has been called the first sealing boom; it sparked the Sealers' War (1810– ) in southern New Zealand.

Australasian sealing measured its output in terms of skins.

By about 1815 sealing in the Pacific had faded in importance. A brief revival occurred from 1823, but this proved very short-lived. Although highly profitable at times and affording New South Wales one of its earliest trade staples, sealing's unregulated character saw its self-destruction. Notable traders from Britain and based in Australia included Simeon Lord, Henry Kable, James Underwood and Robert Campbell. Plummers of London and the Whitneys of New York also became involved.

By 1830 most Pacific seal-stocks had been seriously depleted, and Lloyd's Register of Shipping only showed one full-time sealing vessel on its books. In the North Pacific, the later 1800s saw large harvests of fur seals. These harvests decreased along with fur-seal populations.

Industrial era

Growing from the international Grand Banks fishery, the Newfoundland hunt initially used small schooners. Kill rates averaged 451,000 in the 1830s, and rose to 546,000 annually during the first half of the next decade, which led to a marked decline in the harp seal population that in turn adversely impacted profits in the sealing industry.

Sealing reached its peak in Newfoundland in the 1860s, with the introduction of more powerful and reliable steamships that were capable of much larger range and storing capacity. Annual catches exceeded the 400,000 mark from the 1870s and smaller sealers were steadily pushed out of the market.

The first modern sealing ship was the SS Bear, built in Dundee, Scotland in 1874 as a steamer for sealing. The ship was custom-built for sealing out of St. John's, Newfoundland, and was the most outstanding sealing vessel of her day and the lead ship in a new generation of sealers. Heavy-built with 15-centimetre-thick (6-inch) wooden planks, Bear was rigged as a sailing barquentine but her main power was a steam engine designed to smash deep into ice packs to reach seal herds.

At the time of her arrival in St. John's, there were 300 vessels outfitted each season to hunt seals, but most were small schooners or old sailing barques. The new sealing ships represented by Bear radically transformed the Eastern North Atlantic seal fishery as they replaced the hundreds of smaller sealing vessels owned by merchants in outports around Newfoundland with large and expensive steamships owned by large British and Newfoundland companies based in St. John's. Owned at first by the Scottish firm W. Grieve and Sons, she was acquired in 1880 by R. Steele Junior.

Another famous sealing ship of the era was the Terra Nova, originally built in 1884 for the Dundee whaling and sealing fleet. She was ideally suited to the polar regions and worked for 10 years in the annual seal fishery in the Labrador Sea. Large and expensive ships required major capital investments from British and Newfoundland firms, and shifted the industry from merchants in small outports to companies based in St. John's, Newfoundland. By the late 19th century, the sealing industry in Newfoundland was second in importance only to cod fishing.

The seal hunt provided critical winter wages for fishermen, but was dangerous work marked by sealing disasters that claimed hundreds of lives, such as the 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster involving the SS Southern Cross, the SS Newfoundland, and SS Stephano. The rugged hulls and experienced crews of Newfoundland sealing vessels often led sealers such as Bear and Terra Nova to be hired for Arctic exploration and one sealer Algerine was hired to recover Titanic bodies in 1912. After World War II, the Newfoundland hunt was dominated by large Norwegian sealing vessels until the late 20th century, when the much diminished hunt shifted to smaller motor fishing vessels, based from outports around Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2007, the commercial seal hunt dividend contributed about $6 million to the Newfoundland GDP, a fraction of the industry's former importance.

Environmental protection

The end of the 19th century was marked by the Bering Sea Controversy between the United States and Great Britain over the management of fur seal harvests. In 1867 the United States government purchased from Russia all her territorial rights in Alaska and the adjacent islands, including the Pribilof Islands, the principal breeding-grounds of the seals in those seas. By Acts of Congress, the killing of seals was strictly regulated on the Pribiloff islands and in "the waters adjacent thereto". Beginning in about 1886, it became the practice of certain British and Canadian vessels to intercept passing seals in the open ocean (over three miles from any shore) and shoot them in the water (pelagic sealing). In the summer of 1886, three British Columbian sealers, the Carolena, Onward, and Thornton, were captured by an American revenue cutter, the Corwin, The United States claimed exclusive jurisdiction over the sealing industry in the Bering Sea; it also contended that the protection of the fur seal was an international duty, and should be secured by international arrangement. The British imperial government repudiated the claim, but was willing to negotiate on the question of international regulation.

The issue was taken to arbitration, which concluded in favour of Britain on all points in 1893. Since the decision was in favor of Great Britain, in accordance with the arbitration treaty the tribunal prescribed a series of regulations for preserving the seal herds which were to be binding upon and enforced by both powers. They limited pelagic sealing as to time, place, and manner by fixing a zone of 60 miles (97 km) around the Pribilof Islands within which the seals were not to be molested at any time, and from May 1 to July 31 each year they were not to be pursued anywhere in Bering Sea. Only licensed sailing vessels were permitted to engage in fur sealing, and the use of firearms or explosives was prohibited.

This marked the first attempt at establishing regulations on the sealing industry for environmental purposes. However, these regulations failed because the mother seals fed outside the protected area and remained vulnerable. A joint commission of scientists from Britain and the United States further considered the problem, and came to the conclusion that the pelagic sealing needed to be curtailed. However further joint tribunals did not enact new legal restrictions, and then Japan also embarked upon pelagic sealing.

Finally, the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention severely curtailed the sealing industry. Signed on July 7, 1911, by the United States, Great Britain, Japan, and Russia, the treaty was designed to manage the commercial harvest of fur bearing mammals. It outlawed open-water seal hunting and acknowledged the United States' jurisdiction in managing the on-shore hunting of seals for commercial purposes. It was the first international treaty to address wildlife preservation issues.

The treaty was dissolved with the onset of hostilities between the signatories in World War II. However, the treaty set precedent for future national and international laws and treaties, including the Fur Seal Act of 1966 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972.

Today, commercial sealing is conducted by only five nations: Canada, Greenland, Namibia, Norway, and Russia. The United States, which had been heavily involved in the sealing industry, now maintains a complete ban on the commercial hunting of marine mammals, with the exception of indigenous peoples who are allowed to hunt a small number of seals each year.

Equipment and method

In the Canadian commercial seal hunt, the majority of the hunters initiate the kill using a firearm. Ninety percent of sealers on the ice floes of the Front (east of Newfoundland), where the majority of non-native seal hunting occurs, use firearms.

An older and more traditional method of killing seals is with a hakapik: a heavy wooden club with a hammer head and metal hook on the end. The hakapik is used because of its efficiency; the animal can be killed quickly without damage to its pelt. The hammer head is used to crush the seals' thin skulls, while the hook is used to move the carcasses. Canadian sealing regulations describe the dimensions of the clubs and the hakapiks, and caliber of the rifles and minimum bullet velocity, that can be used.

Modern sealing

Products made from seals

Seal skins have been used by aboriginal people for millennia to make waterproof jackets and boots, and seal fur to make fur coats. Pelts account for over half the processed value of a seal, selling at over C$100 each as of 2006. According to Paul Christian Rieber, of GC Rieber AS, the difficult ice conditions and low quotas in 2006 resulted in reduced access to seal pelts, which caused the commodity price to be pushed up. One high-end fashion designer, Donatella Versace, has begun to use seal pelts, while others, such as Calvin Klein, Stella McCartney, Tommy Hilfiger, and Ralph Lauren, refrain from using any kind of fur.

Seal meat is a source of food for residents of small coastal communities. Meat is sold to the Asian pet food market; in 2004, only Taiwan and South Korea purchased seal meat from Canada. The seal blubber is used to make seal oil, which is marketed as a fish oil supplement. In 2001, two percent of Canada's raw seal oil was processed and sold in Canadian health stores. There has been virtually no market for seal organs since 1998.

Sealing states

- Canada

- Greenland

- Namibia

- Norway

- Russia

Sealing debate

Ecological feasibility

In 2013, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans conducted a population survey. The resulting estimate of the harp seal population was 7.3 million animals, over three times what it was in the 1970s. In 2004, the population estimate was similar: 5.9 million (95% CI 4.6 million to 7.2 million).

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, a much larger population of harp seals migrated to the waters off Newfoundland and Labrador. Settlers began exploiting the population, with kills peaking in the middle of the 1800s. In the first half of the 1840s, 546,000 seals were killed annually. This led to a population decline that adversely affected the industry.

In the 1950s and 1960s an average of over 291,000 seal pups were killed each year. This led to a population decline to less than 2 million seals. Conservationists became alarmed and demanded controls on kill rates. Thus in 1971, Canada instituted a quota system. In the years from 1971 to 1982, an average of 165,627 seals were killed.

In 1983, the European Union banned the import of whitecoat harp seal pup pelts (pelts from pups less than about two weeks of age, when the pups molt). As a result, the market for pelts dropped. The kill rates thus declined in subsequent years to an average of about 52,000 seals from 1983 to 1995. During this time, the harp seal population increased.

After the European Union's ban on whitecoat pelt imports, the Canadian government and sealing industry developed markets for the pelts of beaters. In 1996, the kill rates again increased to over 200,000 each year, except in the year 2000. In 2002 and 2004 to 2006, over 300,000 seal pups were killed each year.

As a result of population concerns, Norway's seal hunt is now controlled by quotas based on recommendations from International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), However, sealing in Norway has declined in recent years, and the quotas have not been reached.

In addition to hunting pressures on the population of harp seals, as ice seals that are dependent on solid sea ice for whelping, the harp seal population is affected by global climate change. The lack of sea ice in recent years has resulted in the drowning deaths of tens of thousands of newborn harp seal pups.

Objections to fur

Animal welfare advocates and organizations, such as PETA, object to the use of real fur when many synthetic "faux fur" alternatives are available.

Economic impact

According to Canadian authorities, the value of the 2004 seal harvest was C$16.5 million, which significantly contributes to seal manufacturing companies, and for several thousand fishermen and First Nations peoples. For some sealers, they claim, proceeds from the hunt make up a third of their annual income. Critics, however, say this represents only a tiny fraction of the C$600-million Newfoundland fishing industry. Sealing opponents also say $16.5 million is insignificant, compared to the funding required to regulate and subsidize the hunt. For 1995 and 1996, there are confirmed reports Fisheries and Oceans Canada encouraged maximum utilization of harvested seals through a $0.20 per pound meat subsidy. The level of subsidy totaled $650,000 in 1997, $440,000 in 1998 and $250,000 in 1999. There were no meat subsidies in 2000. Some critics, such as the McCartneys (see below), have suggested promoting that area as an ecotourism site would be far more lucrative than the annual harvest.

As a culling method

In March 2005, Greenpeace asked the DFO to "dispel the myth that seals are hampering the recovery of cod stocks." In doing so, they implied the seal hunt is, at least in part, a cull designed to increase cod stocks. Cod fishing has traditionally been a key part of the Atlantic fishery, and an important part of the economy of Newfoundland and Labrador. Fisheries and Oceans Canada responded there is no connection between the annual seal harvest and the cod fishery, and that the seal hunt is "established on sound conservation principles."

Public opinion

Internationally, opposition to the seal hunt is comparable to abhorrence about the treatment of animals in other cultural-economic practices such as bull fighting, fox hunts and whaling. Within Canada, public opinion is relative to Canadians' geographic proximity to communities with a historical tradition of participating in the seal hunt, and opposition is higher in urban centres outside of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Protests

Many animal protection groups encourage people to petition against the harvest. Respect for Animals and Humane Society International believe the hunt will be ended only by the financial pressure of a boycott of Canadian seafood. In 2005, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) called for such a boycott in the United States.

Protesters frequently use images of whitecoats, despite Canada's ban on the commercial hunting of suckling pups. The HSUS explains this by saying images of the legally hunted ragged jackets are nearly indistinguishable from those of whitecoats. Also, they state, according to official DFO kill reports, 97% percent of the estimated million harp seals killed in the last four years have been under three months old, and the majority of these are less than one month old.

On 26 March 2006, seven anti-sealing activists were arrested in the Gulf of St. Lawrence for violating the terms of their observer permits. By law, observers must maintain a ten-meter distance between themselves and the sealers. Five of the protesters were later acquitted. In the same month, as part of a counterprotest, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Danny Williams encouraged people in the province to boycott Costco after the retailer decided to stop carrying seal oil capsules. Costco stated politics played no role in their decision to remove the capsules, and on April 4 that year, they were again being sold in Costco stores.

In 2009, the European Union passed a law banning the promotion of imported seal products. The law was approved by the Council of the European Union without debate on 27 July 2009. Denmark, Romania, and Austria abstained. The Canadian government responded to the move by stating that it will take the European Union to the World Trade Organization if the ban does not exempt Canada. Canadian Inuit from the territory of Nunavut have opposed the ban and lobbied European Parliament members against it. Canadian seal hunting issues had been spotlighted in the months leading up to the 2010 Winter Olympics which were held in Vancouver.

Inuit impact

An important distinction between the southern Canadian seal hunt and the Inuit Canadian hunt is that Canadian Inuit typically hunt ringed seals, while the southern Canadian hunt targets the pelt of the harp seal. Greenlandic Inuit hunt and eat both ringed and harp seals. Protests surrounding the southern seal hunt in Canada have historically impacted Canadian and Greenlandic Inuit. Because of the impact of protest, profits surrounding the Inuit hunting of ringed seal fall with any ban on any type of seal product, regardless of exemption. For example, in 1963, prices for high-quality pelts of ringed seals could reach above $20.00 each; these same pelts in 1967, the year of the first major protests, would only sell for $2.50 each, which impacted Inuit in many areas. Protests in other years have resulted in similar decreases in price.

Celebrity involvement

Numerous celebrities have opposed the commercial seal hunt. Rex Murphy has reported celebrities have aided anti-hunt activists since the mid-20th century; Yvette Mimieux and Loretta Swit were recruited to attract the attention of international gossip magazines. Other celebrities who have aligned themselves against the hunt include Richard Dean Anderson, Kim Basinger, Juliette Binoche, Sir Paul McCartney, Heather Mills, Pamela Anderson, Martin Sheen, Pierce Brosnan, Morrissey, Paris Hilton, Robert Kennedy, Jr., Rutger Hauer, Brigitte Bardot, Ed Begley, Jr., Farley Mowat, Linda Blair, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Jackie Evancho.

In March 2006, Brigitte Bardot traveled to Ottawa to protest the hunt, though the prime minister turned down her request for a meeting. During the same month, Paul and Heather Mills McCartney toured the Gulf of Saint Lawrence's sealing grounds, and spoke out against the seal hunt, including as guests on Larry King Live, where the two debated with Danny Williams, the Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador.

In 1978, marine ecologist Jacques Cousteau criticized the seal hunt protest: "The harp seal question is entirely emotional. We have to be logical. We have to aim our activity first to the endangered species. Those who are moved by the plight of the harp seal could also be moved by the plight of the pig – the way they are slaughtered is horrible."

Media

- Alethea Arnaquq-Baril's documentary Angry Inuk details the relationship between seal hunting, Inuit poverty, and the consequences of international trade bans.

- Rudyard Kipling's The White Seal, part of The Jungle Book, describes seal hunting from the seals' point of view, with the central character being a white seal seeking for his seals a safe haven from hunters.

- Jack London's novel The Sea Wolf takes place aboard "the schooner Ghost, bound seal-hunting for Japan" circa 1893.

- Robert Cushman Murphy's book of letters Logbook for Grace describes the expedition of the sealer Daisy in 1912 to South Georgia Island, and includes many details about the brutal elephant seal fishery there.

- Seal clubbers are a class that player characters can choose in the browser-based RPG Kingdom of Loathing.

- The topi enemy in the NES game Ice Climber is a seal in the Japanese version, however it was changed into a yeti in North American and European versions because of concerns over seal hunting references.

See also

In Spanish: Caza de focas para niños

In Spanish: Caza de focas para niños