Inland waterways of the United States facts for kids

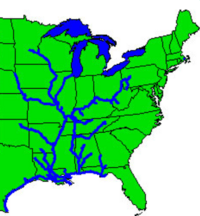

The inland waterways of the United States include more than 25,000 mi (40,000 km) of navigable waters. Much of the commercially important waterways of the United States consist of the Mississippi River System—the Mississippi River and connecting waterways.

Contents

Extent

The Columbia River is the only river on the West Coast (and arguably the entire North American Pacific coast) that is navigable for a significant length. The river is regularly dredged, and freight barges may reach as far inland as Lewiston, Idaho, through a system of locks; however, there are strict draft restrictions beyond the confluence with the Willamette River. The Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, the Snake River, and the Umpqua River are examples of other West Coast rivers that are dredged for navigation. The steep grades and variable flows of most other West Coast rivers make them unsuitable for large boat travel. Also, most large rivers there are dammed, often in multiple places, to supply water for hydroelectricity production and other uses. Mountainous terrain, and a shortage of water, make canals in the West unfeasible as well.

Most navigable rivers and canals in the United States are in the eastern half of the country, where the terrain is flatter and the climate is wetter. The Mississippi River System, including the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW), connects Gulf Coast ports, such as Mobile, New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Houston, and Corpus Christi, with major inland ports, including Memphis, Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, St. Paul, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh. The Lower Mississippi River from Baton Rouge to the Gulf of Mexico allows ocean shipping to connect with the barge traffic, thereby making this segment vital to both the domestic and foreign trade of the United States. The Mississippi River System is connected to the Illinois Waterway, which continues to the Great Lakes Waterway and then to the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Many other eastern rivers are navigable as well, including the Potomac, the Hudson, and the Atchafalaya rivers, which are all dredged by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Title 33 of the United States Code and 33 C.F.R. define the "navigable waters of the United States" and apply certain laws and regulations to those waters. This determination is made by a combination of waters explicitly listed in the law, and general definitions that mean certain waters might or might not be included depending on various factual determinations (such as being "navigable in fact" and the history of use) by the Army Corps of Engineers. Not all waters have had these facts determined, and so are of uncertain status. All water subject to tides are included.

Note that the "Navigable Waters of the United States" listed in 33 C.F.R. 329 are different than those listed as "Waters of the United States" in 33 C.F.R. 328, which is the Clean Water Rule. However, all Navigable Waters, plus those considered navigable-in-fact are included in the general "Waters" definition.

New England district

Vermont waters have been surveyed thoroughly, but the other New England states have some waters of indeterminate status. Flowing waters are navigable from the mouth to source, or mouth to specified point, unless otherwise noted.

- Kennebec River to Moosehead Lake

- Penobscot River to the confluence of the East and West Branch at Medway, Maine

- Lake Umbagog

- Merrimack River to Concord, New Hampshire

- Connecticut River to Pittsburg, New Hampshire

- Lake Champlain

- Lake Memphremagog

- Ompompanoosuc River to Mile 3.8

- Waits River to Mile 0.9

- Black River to Mile 25 in Craftsbury, Vermont

- Battenkill River to Mile 50 in Manchester, Vermont

- Lamoille River to Mile 79 in Greensboro, Vermont

- Missisquoi River to Mile 88.5 in Lowell, Vermont

- Otter Creek to Mile 63.8 in Proctor, Vermont

- Winooski River to Marshfield, Vermont

- Moose River from Passumpsic River to the border of Victory, Vermont

- Nulhegan River, including the East Branch, Black Branch, and Yellow Branch

- Paul Stream

- Passumpsic River and its East Branch to East Haven, Vermont

- Wells River to Groton Pond

- White River

Though navigable-in-fact, parts or all of the following have been excluded from the definition by Congress:

- Park River in Hartford County, Connecticut

- Burr Creek in Bridgeport, Connecticut

- Boston Inner Harbor, Fort Point Channel and South Bay in Boston

- Acushnet River in the harbor of New Bedford and Fairhaven, Massachusetts

- West River in West Haven, Connecticut

- Back Cove in Portland, Maine

- Kenduskeag Stream in Penobscot County, Maine

Efficiency

A principal value of the inland waterways is their ability to efficiently convey large volumes of bulk commodities moving long distances. Towboats push barges lashed together to form a "tow". A tow may consist of four or six barges on smaller waterways and up to over 40 barges on the Mississippi River below its confluence with the Ohio River. A 15-barge tow is common on the larger rivers with locks, such as the Ohio, Upper Mississippi, Illinois and Tennessee rivers. Such tows are an extremely efficient mode of transportation, moving about 22,500 tons of cargo as a single unit. A single 15-barge tow is equivalent to about 225 railroad cars or 870 tractor-trailer trucks. If the cargo transported on the inland waterways each year had to be moved by another mode, it would take an additional 6.3 million rail cars or 25.2 million trucks to carry the load.

The ability to move more cargo per shipment makes barge transport both fuel efficient and environmentally advantageous. On average, a gallon of fuel allows one ton of cargo to be shipped 180–240 mi (290–390 km) by truck (e.g. @ 6–8 mpg‑US (2.6–3.4 km/l) 30 ton load, 450 mi (720 km) by railway, and 514 mi (827 km) by barge. Carbon dioxide emissions from water transportation were 10 million metric tons less in 1997 than if rail transportation had been used. Inland waterways allow tremendous savings in fuel consumption, reduced greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, reduced traffic congestion, fewer accidents on railways and highways, and less noise and disruption in cities and towns.

Commodities

Barges are well suited for the movement of large quantities of bulk commodities and raw materials at relatively low cost. The inland and intracoastal waterway system handles about 630 million tons of cargo annually, or about 17 percent of all intercity freight by volume. These are raw materials or primary manufactured products that are typically stored for further processing or consumption, or transshipped for overseas markets.

- Coal is the largest commodity by volume moving on the inland waterways. The country's electric utility industry depends on the inland waterways for more than 20 percent of the coal they consume to produce electricity.

- Petroleum is the next largest group, including crude oil, gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, heavy fuel oils and asphalt.

- Another large group includes grain and other farm products, most of which moves by waterway to ports on the Lower Mississippi River or Columbia River for export overseas. Sixty percent of the country's farm exports travel through inland waterways.

- Other major commodities include aggregates, such as stone, sand and gravel used in construction; chemicals, including fertilizers; metal ores, minerals and products, such as steel; and many other manufacturers products.

Economic value

Inland and intracoastal waterways directly serve 38 states throughout the nation's heartland as well as the states on the Atlantic seaboard, the Gulf Coast and the Pacific Northwest. The shippers and consumers in these states depend on the inland waterways to move about 630 million tons of cargo valued at over $73 billion annually. States on the Gulf Coast and throughout the Midwest and Ohio Valley especially depend on the inland and intracoastal waterways. Texas and Louisiana each ship more than $10 billion worth of cargo annually, while Illinois, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, and Washington state each ship between $2 billion and $10 billion annually. Another eight states ship at least $1 billion annually. According to research by the Tennessee Valley Authority, this cargo moves at an average transportation savings of $10.67 per ton over the cost of shipping by alternative modes. This translates into over $7 billion annually in transportation savings to economy of the United States.

Maintenance and modernization

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is responsible for 12,000 mi (19,000 km) of the waterways. This figure includes the Intracoastal Waterway. Most of the commercially important inland waterways are maintained by the USACE, including 11,000 mi (18,000 km) of fuel taxed waterways. Commercial operators on these designated waterways pay a fuel tax, deposited in the Inland Waterways Trust Fund, which funds half the cost of new construction and major rehabilitation of the inland waterways infrastructure.

The nearly 12,000 miles (19,000 km) of U.S. inland and intracoastal waterways maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers includes 191 commercially active lock sites with 237 lock chambers. Some locks have more than one chamber, often of different dimensions. These locks provide the essential infrastructure that allows tows to "stair-step" their way through the system and reach distant inland ports such as Minneapolis, Chicago, and Pittsburgh. The locks can generally be categorized by three different sizes, as expressed by length. About 15 percent of the lock chambers are 1,000 to 1,200 ft (300 to 370 m) long, 60 percent are 600 to 999 ft (183 to 304 m) long, and 25 percent are less than 600 feet (180 m) long. Lock widths are mostly 110 feet (34 m). The 1,200-foot (370 m) locks can accommodate a tow of 17 barges plus the towboat, while the 600-foot (180 m) locks can accommodate at most eight barges plus the towboat. The lock size and tow size are critical factors in the amount of cargo that can pass through a lock in a given period of time.

More than 50 percent of the locks and dams operated by the Army Corps of Engineers are over 50 years old. Many of the 600-foot (180 m) locks on the system were built in the 1930s or earlier, including those on the Ohio, Upper Mississippi, Illinois and Tennessee rivers. These projects are approaching the end of their design lives and are in need of modernization or major rehabilitation. Since many of today's tows operate with 12 or more barges, passing through a 600-foot (180 m) lock requires the tow to be "cut" into two sections to pass the lock. Such multiple cuts can be time consuming and cause long queues of tows waiting for their turn to move through the lock.

In the 1960s the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began to modernize the locks on the Ohio River and added 1,200-foot (370 m) chambers that permit a typical tow to pass in a single lockage. This modernization process continues today with the construction of a new dam with twin 1,200-foot (370 m) locks at Olmsted, Illinois, located at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and a second 1,200-foot (370 m) chamber at McAlpine Locks and Dam near Louisville. Modern 1,200-foot (370 m) chambers are also being constructed at Kentucky Lock on the Tennessee River and at the Inner Harbor Lock on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway at New Orleans. Other projects are underway in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Arkansas. In addition, several major rehabilitations are underway. Altogether, this ongoing work represents an investment of over $3.5 billion in inland waterway modernization that will be completed over the next decade. Half this investment will come from fuel taxes paid by the inland towing industry. These projects include not only modern navigation facilities, but also important investments in environmental restoration and management.

Several key navigation improvement feasibility studies are underway throughout the inland waterway system, including on the Upper Mississippi River and Illinois Waterway, Ohio River, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, the Black Warrior River and the Tennessee River. Over the next few years, these studies will identify the navigation and natural environmental actions needed to support the inland waterway system. While annual capital spending for the inland waterway system has averaged about $170 million in recent years, the income stream from fuel tax revenues can support an annual capital investment program of about $250 million without reducing the surplus in the Inland Waterways Trust Fund, whose balance was $385 million at the end of 1999.