Great white shark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Great white shark |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male off Isla Guadalupe, Mexico | |

|

|

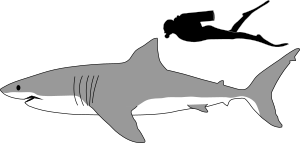

| Size comparison with human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Carcharodon

|

| Species: |

carcharias

|

|

|

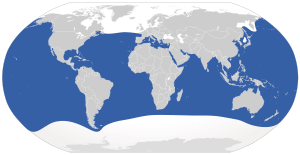

| Global range as of 2010 | |

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major oceans.

Contents

Name

The English name 'white shark' and its Australian variant 'white pointer' is thought to have come from the shark's stark white underside, a characteristic feature most noticeable in beached sharks lying upside down with their bellies exposed.

Distribution and habitat

Great white sharks live in almost all coastal and offshore waters which have water temperature between 12 and 24 °C (54 and 75 °F). It is most common in the United States (Northeast and California), South Africa, Japan, Oceania, Chile, and the Mediterranean including the Sea of Marmara and Bosphorus. One of the densest-known populations is found around Dyer Island, South Africa. Juvenile great white sharks inhabit a more narrow band of temperatures, between 14 and 24 °C (57 and 75 °F), in shallow coastal nurseries. Increased observation of young sharks in areas they were not previously common, such as Monterey Bay on the Central California coast, suggest climate change may be reducing the range of juvenile great white sharks and shifting it toward the poles.

In the Northwest Atlantic, the white shark populations off the New England coast were nearly eradicated due to over-fishing. In recent years, the populations have grown greatly, largely due to the increase in seal populations on Cape Cod, Massachusetts since the enactment of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972.

A 2018 study indicated that white sharks prefer to congregate deep in anticyclonic eddies in the North Atlantic Ocean. The sharks studied tended to favour the warm-water eddies, spending the daytime hours at 450 meters and coming to the surface at night.

Description

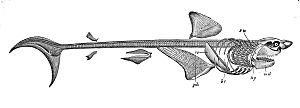

The great white shark has a robust, large, conical snout. The upper and lower lobes on the tail fin are approximately the same size which is similar to some mackerel sharks. A great white displays countershading, by having a white underside and a grey dorsal area (sometimes in a brown or blue shade) that gives an overall mottled appearance.

Teeth

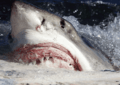

Great white sharks, like many other sharks, have rows of serrated teeth behind the main ones, ready to replace any that break off. When the shark bites, it shakes its head side-to-side, helping the teeth saw off large chunks of flesh.

Eyes

Great white sharks, like other mackerel sharks, have larger eyes than other shark species in proportion to their body size. The iris of the eye is a deep blue instead of black.

Size

The great white shark is notable for its size, with the largest preserved female specimen measuring 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in length and around 2,000 kg (4,410 lb) in weight at maturity. However, most are smaller; males measure 11 to 13 ft (3.4 to 4.0 m), and females measure 15 to 16 ft (4.6 to 4.9 m) on average.

In great white sharks, sexual dimorphism is present, and females are generally larger than males. Adults of this species weigh 522–771 kg (1,151–1,700 lb) on average; however, mature females can have an average mass of 680–1,110 kg (1,500–2,450 lb).

Reported sizes

| Date | Location | Reported length | Reported weight | DUJP | Reported tooth size | Scientifically analyzed length | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 22, 1989 | Ledge Point, Western Australia | 594.4 cm | 2,052.27 kg | 1,300 mm | 51 mm | 594.4 cm | Largest confirmed specimen per John. E. Randall |

| November, 2001 | East Sea, China | 602.0 cm | 2,460.00 kg | Not listed | Not listed | 602.0 cm | Verified by marine biologist Heather M Christianson |

| April 17, 1952 | Streaky Bay, Australia | 609.6 cm | 1,360.77 kg | Not available | Not available | Not available | Enormous white shark periodically hooked by several fisherman; hooked by Alf Dean but broke the line. Estimated to be easily 20 feet in length. |

| August 4, 1983 | Prince Edward Island, Canada | 609.6 cm | 2,213.78 kg | 1,430 mm | 47.5 mm | 609.6 cm | Verified by marine biologist Gordon Hubbell |

| October 13, 1956 | Maguelone, France | 589.0 cm | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Girth estimated at 400 cm |

| June 16, 1996 | Malindi, Kenya | 640.0 cm | 2,200.00 kg | Not listed | Not listed | 570.0 cm | Shark cut apart before it could be photographed and weighed in total |

| May, 1945 | Cojimar, Cuba | 640.8 cm | 3,220.5 kg | Not listed | 44 mm | 633.13 cm | Estimated by John Randall to be 494.37 cm in length, revised upwards per analysis by Maddalena |

| May 14, 1997 | Hualien Country, Taiwan | 670.0 cm | 2,500 kg | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Only photo utilizes forced perspective, likely measurement was lower |

| April 1, 1987 | Kangaroo Island, South Australia | 700.0 cm | 2,500 kg | 1,250 mm | Not listed | 600 cm | Original length of 700 cm cannot be disregarded |

| April 17, 1987 | Filfla, Malta | 714.0 cm | 2,880 kg | 1,120 mm | 46.9 mm | 668 cm - 681 cm | Original reported length of 714 cm is possible |

| May 1978 | Azores | 900.0 cm | 4,546 kg | Not listed | 76.0 mm | 610 cm | Photos examined by John Randall |

| Undetermined | False Bay, South Africa | 1,310.64 cm | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Referred to by Lawrence G. Green in book |

| June 5, 1975 | Long Island, NY | 914.14 cm | Not listed | 762.00 mm | Not listed | Not listed | Sited by charter captain Paul Sundberg. Harpooned but broke away, left a 30 in lower bite mark in the bottom of his boat |

| June 1978 | Montauk Point | 762.00 cm | 1,360.78 kg | Not listed | Not listed | Not listed | Harpooned by charter captain John Sweetman, towed boat 30 miles before breaking free. Also spotted by charter captain Paul Sundberg and confirmed visually as a great white. |

| March 2008 | Sandun, China, March 2008 | 1,000.00 cm | 2,267.96 kg | Not listed | Not listed | 614.5 | Weight considered far too low for shark of that length, would have been 9,772.37 kg if size was accurate |

| Jan 17, 2019 | Hawaii | 609.6 cm | 2,267.96 kg | Not listed | Not listed | 609.6 cm | Deep Blue was spotted off of Mexico in 2013, and again off of Hawaii in 2019 |

| June 1930 | Grand Mahan | 1,127.76 cm | 2,267.96 kg | Not listed | Not listed | 517.6 cm - 812.5 cm | John Randall estimated 517 cm based on a 28 mm tooth; scaling size based on quantity of reported liver oil yielded gives larger estimate |

| November 6, 1987 | Cowes, Phillip Island, Victoria, Australia | 633 cm | 2,306.52 kg | Not listed | 50.8 mm | 633 cm | Stomach contained an entire seal. Teeth were 2 inches long. |

Lifespan and reproduction

According to a 2014 study, the lifespan of great white sharks is estimated to be as long as 70 years or more, well above previous estimates, making it one of the longest lived cartilaginous fishes currently known. According to the same study, male great white sharks take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, while the females take 33 years to be ready to produce offspring.

The great white has an 11-month gestation period. The shark pup's powerful jaws begin to develop in the first month. The unborn sharks participate in oophagy, in which they feed on ova produced by the mother. Delivery is in spring and summer. The largest number of pups recorded for this species is 14 pups from a single mother measuring 4.5 m (15 ft)

Diet

Great white sharks are carnivorous and prey upon fish (e.g. tuna, rays, other sharks), cetaceans (i.e., dolphins, porpoises, whales), pinnipeds (e.g. seals, fur seals, and sea lions), sea turtles, sea otters (Enhydra lutris) and seabirds. Great whites have also been known to eat objects that they are unable to digest. Juvenile white sharks predominantly prey on fish, including other elasmobranchs, as their jaws are not strong enough to withstand the forces required to attack larger prey such as pinnipeds and cetaceans until they reach a length of 3 m (9.8 ft) or more, at which point their jaw cartilage mineralizes enough to withstand the impact of biting into larger prey species. Upon approaching a length of nearly 4 m (13 ft), great white sharks begin to target predominantly marine mammals for food, though individual sharks seem to specialize in different types of prey depending on their preferences.

Predators

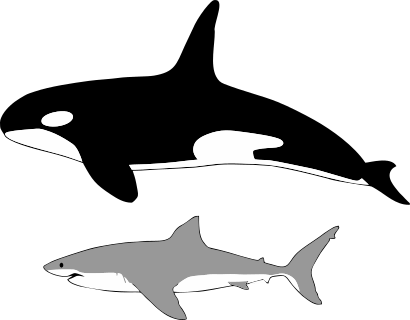

The great white shark has only one recorded natural predator, the orca.

Adaptations

Electromagnetic detection

Great white sharks, like all other sharks, have an extra sense given by the ampullae of Lorenzini which enables them to detect the electromagnetic field emitted by the movement of living animals. Great whites are so sensitive they can detect variations of half a billionth of a volt. At close range, this allows the shark to locate even immobile animals by detecting their heartbeat. Most fish have a less-developed but similar sense using their body's lateral line.

Camouflage

In 2022, research in South Africa suggested that the great white shark has the ability to change colours to camouflage itself depending on the hormones it gives off. Different hormones would change the colour of the skin from white to grey. Skin dosed with adrenaline would turn lighter, with melanocyte-stimulating hormone causing melanocyte cells to dissipate thus making the shark's skin a darker colour, although hormone mediated color change is not fully validated due to the limited number of test subjects (i.e. great whites). The camo shark hypothesis is supported by the fact that zebra sharks can change their colour as they age, and rainbow sharks can lose colour due to stress and aging.

Ecology and behaviour

This shark's behaviour and social structure are complex. In South Africa, white sharks have a dominance hierarchy depending on the size, sex and squatter's rights. Females dominate males, larger sharks dominate smaller sharks, and residents dominate newcomers.

When hunting, great whites tend to separate and resolve conflicts with rituals and displays. White sharks rarely resort to combat although some individuals have been found with bite marks that match those of other white sharks. This suggests that when a great white approaches too closely to another, they react with a warning bite. Another possibility is that white sharks bite to show their dominance.

White sharks are generally very curious animals, display intelligence and may also turn to socializing if the situation demands it.

Breaching behaviour

A breach is the result of a high-speed approach to the surface with the resulting momentum taking the shark partially or completely clear of the water. This is a hunting technique employed by great white sharks whilst hunting seals. This technique is often used on cape fur seals at Seal Island in False Bay, South Africa. Because the behaviour is unpredictable, it is very hard to document. It was first photographed by Chris Fallows and Rob Lawrence who developed the technique of towing a slow-moving seal decoy to trick the sharks to breach. Great white sharks can reach speeds of up to 40 km/h (25 mph) and can at times launch themselves more than 10 ft (3 m) into the air. Just under half of observed breach attacks are successful.

Relationship with humans

Shark culling

Shark culling is the deliberate killing of sharks by a government in an attempt to reduce shark attacks; shark culling is often called "shark control". These programs have been criticized by environmentalists and scientists—they say these programs harm the marine ecosystem; they also say such programs are "outdated, cruel, and ineffective".

Attacks on boats

Great white sharks infrequently bite and sometimes even sink boats. Only five of the 108 authenticated unprovoked shark bite incidents reported from the Pacific Coast during the 20th century involved kayakers. In a few cases they have bitten boats up to 10 m (33 ft) in length. They have bumped or knocked people overboard, usually biting the boat from the stern. In one case in 1936, a large shark leapt completely into the South African fishing boat Lucky Jim, knocking a crewman into the sea. Tricas and McCosker's underwater observations suggest that sharks are attracted to boats by the electrical fields they generate, which are picked up by the ampullae of Lorenzini and confuse the shark about whether or not wounded prey might be nearby.

Shark tourism

Cage diving is most common at sites where great whites are frequent including the coast of South Africa, the Neptune Islands in South Australia, and Guadalupe Island in Baja California. The popularity of cage diving and swimming with sharks is at the focus of a booming tourist industry. A common practice is to chum the water with pieces of fish to attract the sharks. These practices may make sharks more accustomed to people in their environment and to associate human activity with food; a potentially dangerous situation. By drawing bait on a wire towards the cage, tour operators lure the shark to the cage, possibly striking it, exacerbating this problem. Other operators draw the bait away from the cage, causing the shark to swim past the divers.

At present, hang baits are illegal off Isla Guadalupe and reputable dive operators do not use them. Operators in South Africa and Australia continue to use hang baits and pinniped decoys. In South Australia, playing rock music recordings underwater, including the AC/DC album Back in Black has also been used experimentally to attract sharks.

Companies object to being blamed for shark bite incidents, pointing out that lightning tends to strike humans more often than sharks bite humans. Their position is that further research needs to be done before banning practices such as chumming, which may alter natural behaviour. One compromise is to only use chum in areas where whites actively patrol anyway, well away from human leisure areas. Also, responsible dive operators do not feed sharks. Only sharks that are willing to scavenge follow the chum trail and if they find no food at the end then the shark soon swims off and does not associate chum with a meal. It has been suggested that government licensing strategies may help enforce these responsible tourism.

-

Putting chum in the water

Conservation

Fishermen target many sharks for their jaws, teeth, and fins, and as game fish in general. The great white shark, however, is rarely an object of commercial fishing, although its flesh is considered valuable.

The species faces numerous ecological challenges which has resulted in international protection. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the great white shark as a vulnerable species, and it is included in Appendix II of CITES. It is also protected by several national governments, such as Australia (as of 2018). Due to their need to travel long distances for seasonal migration and extremely demanding diet, it is not logistically feasible to keep great white sharks in captivity; because of this, while attempts have been made to do so in the past, there are no known aquariums in the world believed to house a live specimen.

In popular culture

The great white shark is depicted in popular culture as a ferocious man-eater, largely as a result of the novel Jaws by Peter Benchley and its subsequent film adaptation by Steven Spielberg. Humans are not a preferred prey, but nevertheless it is responsible for the largest number of reported and identified fatal unprovoked shark attacks on humans. However, attacks are rare, typically occurring fewer than 10 times per year globally.

Interesting facts about the great white shark

- It is the only known surviving species of its genus Carcharodon.

- Great white sharks can swim at speeds of 25 km/h (16 mph) for short bursts and to depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).

- The great white shark is arguably the world's largest-known extant macropredatory fish.

- A complete female great white shark specimen in the Museum of Zoology in Lausanne, and claimed by De Maddalena et al. (2003) as the largest preserved specimen, measured 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in total body length with the caudal fin in its depressed position, and is estimated to have weighed 2,000 kg (4,410 lb).

- The largest great white recognized by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) is one caught by Alf Dean in southern Australian waters in 1959, weighing 1,208 kg (2,663 lb).

- In 2008, a team of scientists led by Stephen Wroe conducted an experiment to determine the great white shark's jaw power and findings indicated that a specimen massing 3,324 kg (7,328 lb) could exert a bite force of 18,216 newtons (4,095 lbf).

- Great white sharks rely on the fat and oils stored within their livers for long-distance migrations across nutrient-poor areas of the oceans.

- The great white shark is one of only a few sharks known to regularly lift its head above the sea surface to gaze at other objects such as prey.

- Of all shark species, the great white shark is responsible for by far the largest number of recorded shark bite incidents on humans, with 272 documented unprovoked bite incidents on humans as of 2012.

- A 2014 study estimated the population of great white sharks along the California coastline to be approximately 2,400.

Images for kids

-

A shark scavenging on a whale carcass in False Bay, South Africa

-

Great white shark in the Monterey Bay Aquarium in September 2006

See also

In Spanish: Tiburón blanco para niños

In Spanish: Tiburón blanco para niños

- List of sharks

- List of threatened sharks

- Outline of sharks

- Shark culling