Chinese New Year facts for kids

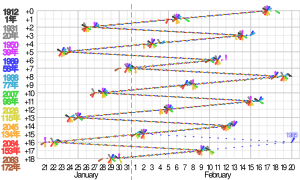

Chinese New Year, known in China as the Spring Festival and in Singapore as the Lunar New Year, is a holiday on and around the new moon on the first day of the year in the traditional Chinese calendar. This calendar is based on the changes in the moon and is only sometimes changed to fit the seasons of the year based on how the Earth moves around the sun. Because of this, Chinese New Year is never on January 1. It moves around between January 21 and February 20.

The Chinese New Year is one of the most important holidays for Chinese people all over the world. Its 7th day used to be used instead of birthdays to count people's ages in China. The holiday is still used to tell people which "animal" of the Chinese zodiac they are part of. The holiday is a time for gifts to children and for family gatherings with large meals, just like Christmas in Europe and in other Christian areas. Unlike Christmas, the children usually get gifts of cash in red envelopes (hongbao) and not toys or clothes.

Chinese New Year used to last 15 days until the Lantern Festival on the year's first full moon. Now, it is a national holiday in the Republic and People's Republic of China, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia. It is also celebrated in some parts of Thailand. In some places, only the first day or three days are celebrated. In the PRC, nearby weekends are changed to create a 7-day-long "Golden Week."

Contents

Name

The Mandarin Chinese name of the holiday is Chūn Jié, which means "Spring Festival." This is why it is often called the "Spring Festival" by Chinese speakers of English, even though the holiday always occurs in the winter months of January or February. Its name is written [] Error: {{Lang}}: no text (help) in traditional Chinese writing and [] Error: {{Lang}}: no text (help) in the easier writing now used by mainland China and Singapore. The Republic of China began to use this name in the 1910s, after it began to use the European calendar for most things.

Before that, the holiday was usually just called the "New Year." Because the traditional Chinese calendar is mostly based on the changes in the moon, the Chinese New Year is also known in English as the "Lunar New Year" or "Chinese Lunar New Year." This name comes from "Luna," an old Latin name for the moon.

Day of the New Year

| Animal | Chinese | Dates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trad. | PRC | ||||

| Rat | 鼠 | February 19, 1996 | February 7, 2008 | January 25, 2020 | |

| Ox Cow |

牛 | February 7, 1997 | January 26, 2009 | February 14, 2021 | |

| Tiger | 虎 | January 28, 1998 | February 14, 2010 | February 25, 2022 | |

| Rabbit | 兔 | February 16, 1999 | February 3, 2011 | January 27, 2023 | |

| Dragon | 龍 | 龙 | February 5, 2000 | January 23, 2012 | February 14, 2024 |

| Snake | 蛇 | January 24, 2001 | February 10, 2013 | January 19, 2025 | |

| Horse | 馬 | 马 | February 12, 2002 | January 31, 2014 | February 21, 2026 |

| Goat | 羊 | February 1, 2003 | February 19, 2015 | February 26, 2027 | |

| Monkey | 猴 | January 22, 2004 | February 8, 2016 | January 14, 2028 | |

| Rooster Chicken |

雞 | 鸡 | February 9, 2005 | January 28, 2017 | February 2, 2029 |

| Dog | 狗 | January 29, 2006 | February 16, 2018 | February 17, 2030 | |

| Pig | 豬 | 猪 | February 18, 2007 | February 5, 2019 | January 20, 2031 |

Chinese New Year always starts on a new moon, when the Moon is between the Earth and Sun and the night sky is dark. Because new moons happen about every 29.53 days but the year set by Pope Gregory XIII is 365.2425 days long, the Chinese holiday moves to different days each year. The Chinese calendar adds a 13th month every so often to keep the seasons in the right place, so the first day of the new year always happens between January 21 and February 20 on the 2nd or 3rd new moon after the 1st day of winter. The chart on the right gives the day of each Chinese New Year from AD 1996 to 2031.

Traditional counting

In the past, the Chinese emperors did not number their years from one place. Instead, they gave names to eras (groups of years) any time they wanted. In the same way, people in China and around East Asia did not count their ages from zero or add one year at every birthday. They counted birth as the start of their 1st year and added another year upon the 7th day of the New Year, which they called People's Day (Rénrì). (Today, it is much more common in China to count age starting at zero and add years at birthdays, like in English-speaking countries.)

Animals of the New Year

The Chinese used to keep time using 2 different lists of characters, known in English as the 10 Heavenly Stems and the 12 Earthly Branches. Each is said to be yin (dark or female) or yang (bright or male), so that when they are put together they make a list of 60 pairs. (The current list began in 1984 and will end in 2043.) Later, each of the stems was also said to match one of the 5 Chinese elements—wood, fire, dirt, metal, or water—and each of the branches was said to be a different animal: Rat, Ox & Cow, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster & Chicken, Dog, and Pig.

Today, Chinese people don't use these lists to count hours, days, or years, but many still pay attention to the animal of the year when someone was born. Just like with the European zodiac, some people think the year's animal can change how someone thinks and acts. They even think it can change whether a marriage will be a happy one or not. Newspapers pay writers to give them ideas for how lucky different animals will be during the coming week. Many parents even time their children's birth within a year or two to give them the best animal sign.

History

Chinese tradition said that the Chinese calendar began during the 60th year of the reign of the Yellow Emperor in 2637 BC, with New Year celebrations beginning in that year. As far as we now know, it's much less old than that. Parts of the old ways of counting time given above are at least as early as 1250 BC, during the Shang times. Most of it was known by the Zhou (11th–3rd centuries BC). From eastern China, the calendar and its new year spread to nearby places like Vietnam (111 BC), Korea (before AD 270), Japan (AD 604), and Tibet (around AD 641). It also followed people who moved from China to their new homes in Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and other places.

The Shang kings (16th–11th centuries BC) gave special gifts to their gods and dead family members during the winter of each year.

Under the Zhou, people were having harvest festivals like today's Mid-Autumn Festival by about 1000 BC.

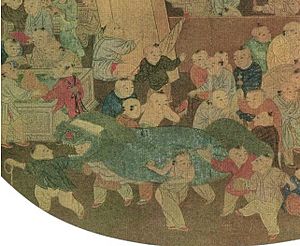

By the early Han, people were counting their birthdays from People's Day on the 7th day of the New Year. Dragon dances had appeared by the time of the Han. People thought that Chinese dragons like Yinglong and Shenlong were kinds of gods who had power over where the water in rivers and canals went and when the water in clouds would fall as rain. Because this was very important for farming, dragon dances could happen all through the year when rain was needed.

Lion dances were probably newer. There was lion dancing under the Tang and in Japan by the 8th century, but people still thought of it as a foreign dance used by Buddhists. Today, people talk about "Northern" and "Southern" kinds of lion dances. The special northern kind began under the Southern Song (12th–13th century). The special southern kind began in Guangdong later, maybe under the Ming (14th–17th century).

As part of other changes, the Meiji Emperor of Japan ordered in 1873 that the new year celebrations of his country would be held on January 1. Today, most of the traditional Japanese celebrations now occur on that day, not at the same time as Chinese New Year. In 1928, the Nationalist Party of China tried to change the Chinese celebrations to January 1, too, but this completely failed as the Chinese people protested or ignored the new laws and continued as usual.

In 1967, as part of Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, the PRC's government did not celebrate or allow special time off work for the traditional new year. Public celebrations returned by the time of Deng Xiaoping's Opening Up Policy in the 1980s. Since the year 2000, Chinese New Year has been one of the PRC's Golden Weeks: there are three days of paid time away from work during the first few days and two weekends around it are moved to make a 7-day-long holiday. These Golden Weeks copied a similar Japanese idea.

In 2015, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah of Brunei made tough new laws about the celebration of Chinese New Year. This was part of his introducing traditional Islamic law to the country.

Events

Mainland China

People in China usually try to be together with their families for at least the first few days of the holiday. Because of the large number of Chinese people and the many people who work away from their hometowns, this "spring traveling" (chunyun) is the biggest movement of people in the world every year.

A "reunion dinner" happens on the evening of the last day of the traditional year ("New Year's Eve"). Older and married people give younger ones cash in red envelopes known as hongbao in Mandarin Chinese or laisee in Cantonese. China Central Television puts on a long show with many star actors, singers, and dancers. It is usually the most-watched TV show in the world each year. Lately, its ads have also become some of the world's most expensive, although they are still behind those aired during the US Super Bowl.

Children are allowed to stay up until midnight. Around 12 o'clock, the new year is welcomed with public fireworks and private firecrackers. Children are told the story of a monster called "Nian" ("Year") who was scared away by a town's loud noises and bright lights on a Chinese New Year long ago. Some people call or send text messages and e-mails to say "Happy New Year!"

Temples also have special fairs with lots of street food. There are Peking opera and martial arts shows and lion and dragon dances in major cities. The dragons can be very long. The longest dragon so far has been a little over 3.5 miles (5.6 km) in Hong Kong in 2012. Hong Kong also has special horse races at its racetrack. Guangzhou has several special flower festivals.

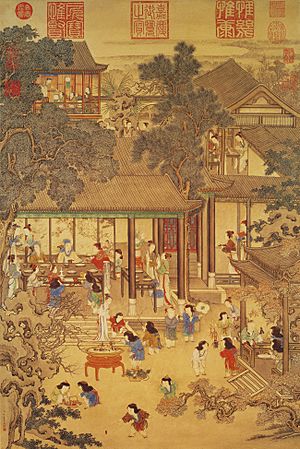

The day of the new year's first full moon is called the Lantern Festival. Many streets and homes are decorated with old paper lanterns. In the past, this was one of the few days of the year when the women of families with lots of money could go outside their homes. They walked the streets nearby with their maids and could say hello to people outside their family. This still causes the festival to make people think of young adults meeting their future husband or wife.

-

Northern lion dancing (2002)

-

A fire dragon dance (2003)

-

A Shanghainese man setting off firecrackers (2008)

Taiwan

In Taiwan, most events and traditions are the same as those in China. The most important special event is the Yanshui Beehive Fireworks Festival, where fireworks are shot straight into the people watching the show. Being hit is supposed to bring good luck, but this used to be very unsafe. Today, people wear special hard hats, (helmets), and thick clothes to protect themselves. Another special event is the "Bombing of Master Handan" in Taitung, where people throw firecrackers straight at the members of a parade who are wearing only red underwear and towels. Taiwan's Hakka people have a tradition like this, where firecrackers are thrown at dragon dancers as they parade through towns. The dragon is then burned at the end of the dance. Taipei's City Lantern Festival also goes on for most of the holiday, not just during the 1-day Lantern Festival at the end.

Philippines

Chinese New Year is a national holiday in the Philippines. People do not get money without working, but anyone who does have to work on the "special non-working day" gets 130% of the usual pay. Binondo—sometimes considered the world's oldest Chinatown—sees a lot of traditional celebrations, such as lion and dragon dances. Its people also try to pay back any money they owe before the New Year.

In 2001, Davao City stopped letting people use fireworks because its people were hurting themselves too much. Their mayor Rodrigo Duterte became president of the country and said that he wanted to stop fireworks everywhere. As president, however, he has continued to let people use them.

Indonesia

Chinese New Year (Indonesian: Imlek) is a 1-day national holiday in Indonesia. Chinese people have lived there since at least the 15th century. Indonesian president Suharto stopped Chinese Indonesians from celebrating Chinese New Year in 1967. Things changed after the fall of Suharto in 1998, and Indonesia made Chinese New Year a national holiday for everyone in 2003.

Today, Chinese Indonesians celebrate the holiday much as people in China do. Dragon and lion dances are common at shopping centers, which sometimes have special sales to let Chinese people buy new (often red) clothes to wear for the holiday. People cannot use fireworks in most of Indonesia, but some cities like Jakarta let people use firecrackers.

Some older Chinese traditions still survive in Indonesia. Like in the Philippines, people try to pay back any money they owe before the New Year. People also try not to lend any money during the holiday, because they think it will make them have to keep lending money for the whole year. Doors and windows are opened on the day before the New Year to "let the old year out," and people wake up early the next morning so they don't stay lazy the whole year. The red envelopes of money (Hokkien: âng-pau) are given on the morning of New Year's Day, not at dinner on the night before it. Many make special trips to one of Indonesia's Chinese temples at some time during the holiday.

It is also still common to leave some food at the table for dead family members and to give them gifts as the New Year begins. Chicken is usually eaten with the head, tail, and feet still on, showing "completeness." Though white rice is eaten, fresh white tofu is not eaten because in Chinese culture its color makes some people think of death and bad luck.

Malaysia

Most of Malaysia gets two days off work for Chinese New Year: the New Year itself and the day after it. Some people still follow the tradition that the second day is used for married women to visit their parents, after visiting her husband's family on Chinese New Year's Day. Most Chinese Malaysians take the entire week off of work, despite the shorter length of the national holiday. Traditional Chinese use the 3rd day of the New Year to visit the resting places of family members who died in the last 3 years; people without a death in their family stay home.

An unusual tradition in Malaysia is the idea of "open house" dinners, especially on the 2nd and 3rd nights of the holiday. Guests, friends, and even strangers from different races and religions can be let in to enjoy large dinners together. The Malaysian government even has its own "open houses" at community halls.

In addition to fireworks at the beginning of the New Year, many people light them on the 9th day of the holiday to celebrate the birthday of the Jade Emperor, the boss of the Chinese gods. The day was used for a special Hokkien New Year. A story tells that one time in the past, the Hokkien people had to hide from robbers for 8 days in a sugarcane field. Because of this story, lots of sugarcane is used for Malaysian decorations for Chinese New Year.

Teochew-style Yusheng, a fish-and-noodle dish, is common in Malaysia, where it is called "yee sang" or "prosperity toss." A restaurant in Seremban started getting people to eat it by throwing it high in the air for good luck in the 1940s, and people had so much fun that they have done it ever since. Another common dish is "steam boat," a kind of seafood hot pot. As in other Chinese places, eating and giving away oranges and tangerines is common in Malaysia. A special tradition is for women with no boyfriend or husband to throw an orange into the sea to find a man. Some now write their telephone numbers on the oranges they throw, and men will use boats to go out and get the fruit.

Many people in Malaysia who believe in Islam and Hinduism have also started giving red envelopes full of money.

Singapore

Singapore, like Malaysia, has a national holiday for Chinese New Year and the day after it. It also sees many "steam boat" hot pot dinners. In 1972, the government stopped people from using their own fireworks during the holiday. Worried that people would find the next celebration less fun, they began the Chingay Parade the next year in 1973. In 1977, Indians and Malays joined the parade, which happens on the 8th day of the New Year. The parade is now the biggest in Asia, with more than 10,000 people in it and floats that show every animal of the circle of Chinese years and the money god Cai Shen. More than 100,000 come to see it in person, and millions of people see it on TV. There are still government firework shows, and the people of Singapore now make noise during the holiday by hitting bamboo sticks together.

Holiday shopping and street shows are centered on Chinatown. Downtown, the holiday is used as a showcase for Chinese arts and customs.

Brunei

Chinese New Year, the day before it, the day after it, and the Lantern Festival are national holidays in Brunei. The country has had a large number of Chinese people since the 1930s and 40s, and the sultan sometimes comes to their New Year celebrations. Since 2015, however, Brunei has set out tough Islamic laws that try to stop Muslims from joining or even seeing the Chinese celebrations. Lion dances are allowed only at the last Chinese temple in Brunei, at Chinese schools, and at the homes of the Chinese. Only Chinese people can join the dance. People cannot use fireworks or firecrackers, and dances must stop during the hours of Islamic prayers. Breaking these rules risks as much as B$20,000 (Brunei dollars) and 5 years in jail.

Korea

The Chinese New Year celebrations in North and South Korea are known as Korean New Year. The time in Beijing is 1 hour different from the time in the Korean capital cities of Pyongyang and Seoul. About one time every 24 years, this makes the Korean New Year start on the day after the Chinese New Year.

The Korean holiday is very close to the Chinese one, with families gathering, children being very nice to their parents and grandparents, and older people giving gifts of money to the young. The Korean holiday has different traditional foods and games, though.

Vietnam

The Chinese New Year celebrations in Vietnam are known as Tet. Like in Korea, the Vietnamese New Year is mostly the same as China's, with families gathering, children saying nice things to their parents and grandparents, and older people giving gifts of money to the young. There are some different foods and traditions, like their New Year tree or special games. Some of the differences come from changes in China: Tet sees more people do nice things for their dead family members. In China, most of the traditions like that were moved to Tomb Sweeping Day at the beginning of April.

Other places

The largest US and Canadian celebrations happen in Chinatowns. People eat Chinese food, give gifts, and have dragon parades that sometimes include marching bands. There is no national holiday with time off work, but different events go on for the full traditional 2 weeks up to the Lantern Festival.

In the United Kingdom, the celebration in London's Chinatown and Trafalgar Square drew 500,000 people in 2015.

The holiday is also so important to China that many world leaders will take time to send their good wishes to China and the Chinese people.

-

A German postcard about Chinese New Year in Los Angeles, USA (1903)

-

A Chinese American mother and child dressed for the New Year in LA (1904)

-

Chinese Americans get the special clothes ready for a lion dance team in LA (1953)

-

Southern lion dancing in New York City, USA (2008)

-

Fireworks in Mexico City's Chinatown (2009)

Customs

Most traditional customs have to do with getting more good luck for the new year and staying away from anything unhappy.

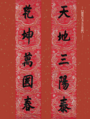

Houses are cleaned completely. In former times, sacrifices were made to the gods and dead family members in the days before the holiday. People hang up decorations, especially pairs of Chinese poems (couplets) on either side of their doors. Some put pictures of Taoist gods on the doors to scare away bad things. Live plants suggest growth, and flowers suggest coming fruits. Pussy willow is common in some places because its Chinese name sounds like "money coming in." It is common for big decorations to look like the animal for the new year.

People used to welcome the New Year with anything that made loud noises, including drums, cymbals, or even woks and pots. The exact traditions were different in different parts of China. Fireworks and firecrackers became more and more common everywhere, but lately many places have stopped letting most people use them because of the danger of people hurting themselves, of fire, and of air pollution that can make people sick. There are still big firework shows in most big cities with many Chinese people, but the city government will put on the show while everyone else watches.

Visits to people's houses are done in new or well-kept clothes. People wear more red than usual, which makes them think of happy times like weddings, and wear less black and white, which makes some think of sad times like funerals.

There are some common things people say to wish good luck to each other, the most important being gōngxǐ fācái ("congratulations that you are now rich"). People try not to say bad words, tell ghost stories, or talk about death. Some even stay away from the number four, which sounds like "death" in Chinese. Crying babies are also thought to be bad luck, and family members will try to keep children happy during visits.

There are some old customs done by hardly anyone. In old China, they didn't sweep or wash clothes on New Year's Day itself. They were afraid of cleaning away good luck together with the dirt. For the same reason, some people did not wash their hair and were very careful not to break any tools. The 5th or 6th day after New Year, when they cleaned and threw away or burned all the trash, was a day for "sending off" the god of Being Poor, one of the sons of Zhuanxu. In the same way, people near Beijing thought that it was unlucky to cook or steam food for the first 5 days of the New Year. They would cook all of their next week of food 2 days before it, so it was ready for the reunion meal. On People's Day, the 7th day of the holiday, people used to wear special headbands and thought good weather meant good luck for everyone in the coming year. Everyone used it to count their age, even when it was not their birthday. None of that is common anymore.

Taoist traditions that are less common now are giving gifts to the Chinese gods. It was thought that gifts would make the gods be nicer to the house and not bring bad luck. Now, fewer people worry about those things.

Food

The reunion dinners on the day before Chinese New Year are often the largest and most expensive of the year. Some families use special and expensive foods to look good to others; others use meaningful foods to bring luck. Jiaozi (a kind of dumpling) are common in northern China. People think they look like the old Chinese silver bars and hold luck inside. Egg rolls and spring rolls like lumpia can also be made to look like golden bars, and oranges and tangerines are thought to look like gold coins. Noodles like yīmiàn or Filipino pancit are eaten uncut to wish for long life. Other foods are eaten because their Chinese names sound like lucky words.

Some Chinese also put out "Trays of Togetherness," dishes with eight different kinds of snack foods. Some common things to put in these trays are kumquats, longans, pieces of coconut meat, peanuts, candies, and melon and lotus seeds. Eight is a lucky number to many Chinese people, like seven in Europe and other places. These dishes are very common among Malaysian and Indonesian Chinese.

For the Lantern Festival, the special food is yuanxiao, small balls of sticky rice in a sweet soup. Lichun always happens near the Chinese New Year as well. It is celebrated by eating spring pancakes (chūnbǐng).

-

Niangao, small cakes of sticky rice

-

Tangerines with a hongbao

-

Chinese dumplings

-

A traditional gift of food, drinks, and incense to the gods, especially the kitchen god

Interesting facts about Chinese New Year

- About 1/4 of the world's population celebrates Chinese New Year.

- San Francisco has held a Chinese New Year celebration since the 1860s, during the gold rush and claims that its Chinese New Year parade is the biggest celebration outside of Asia.

- People try to eat as many dumplings as they can on Chinese New Year because dumplings represent wealth.

- Pears are considered rude to give as a gift because the Chinese word for pears (梨 lí /lee/) sounds the same as the word for leaving or parting (离 lí).

- In China, females are said to be marriageable up to 30, and males before 32. Because of this, some people rent a boyfriend or girlfriend for Chinese New Year to make visiting their families easier.

- An old Chinese belief says that the second day of the new year is the birthday of all dogs and that people should be extra kind to dogs that day.

- According to Chinese tradition, whatever someone does on New Year’s Day sets the precedent for the rest of the year.

- Chinese supermarkets report that sales of adult diapers increase by 50% during the Chinese New Year traveling season.

Images for kids

-

The largest Chinese New Year parade outside Asia, in Chinatown, Manhattan.

-

Spring couplets written by Qianlong Emperor of Qing dynasty, now stored in The Palace Museum

-

Incense is burned at the graves of ancestors as part of the offering and prayer rituals.

-

Chinese New Year's celebrations, on the eighth day, in the Metro Vancouver suburb of Richmond, British Columbia, Canada.

-

One version of niangao, New Year rice cake

-

Chinese New Year festival in Chinatown, Boston

-

Decorations on the occasion of Chinese New Year – River Hongbao 2016, Singapore

-

Southeast Asia's largest temple – Kek Lok Si near George Town in Penang, Malaysia – illuminated in preparation for the Chinese New Year.

-

Lanterns hung around Senapelan street, the Pekanbaru Chinatown

-

Gaya Street in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia filled with Chinese lanterns during the New Year celebration.

-

Cian cui is an Indonesian tradition during the Chinese New Year which involves splashing others with water. Photograph taken in Selatpanjang, Riau, Indonesia.

See also

In Spanish: Año Nuevo chino para niños

In Spanish: Año Nuevo chino para niños