Deng Xiaoping facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Deng Xiaoping

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

邓小平

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Deng during a visit to the US in 1979

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 13 September 1982 – 2 November 1987 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Li Xiannian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhao Ziyang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Chen Yun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Military Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office Party Commission: 28 June 1981 – 9 November 1989

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hua Guofeng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jiang Zemin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office State Commission: 6 June 1983 – 19 March 1990

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jiang Zemin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 March 1978 – 18 June 1983 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zhou Enlai (until 1976) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Deng Yingchao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 22 August 1904 Guang'an, Sichuan, Qing Empire |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 19 February 1997 (aged 92) Beijing, China |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Chinese Communist (from 1924) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

Zhang Xiyuan (张锡瑗)

(m. 1928; died 1929)Jin Weiying (金维映)

(m. 1931–1939)Zhuo Lin

(m. 1939) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relations | Deng Zhuodi (grandson) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | People's Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Central institution membership

1975–1976, 1977–1987: 10th, 11th, 12th Politburo Standing Committee

1956–1967: 8th Politburo Standing Committee 1975–1976, 1977–1987: 10th, 11th, 12th Politburo 1956–1967: 8th Politburo 1945–1967, 1973–1976, 1977–1987: 7th, 8th, 10th, 11th, 12th Central Committee 1954–1967, 1973–1976, 1977–1989: 8th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th Central Military Commission 1978–1997: 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th National People's Congress 1959–1964: 2nd National People's Congress Other political offices held

1977–1982: Vice Chairman, Central Committee

1977–1980: 1st-ranked Vice Premier 1975–1976: Vice Chairman, Central Committee 1975–1976: 1st-ranked Vice Premier 1973–1975: Vice Premier 1964–1965: Head, Organization Department 1954–1967: Vice Premier 1953–1954: Director, Office of Communications Military offices held

1977–1981: Vice Chairman, Central Military Commission

1975–1976: Vice Chairman, Central Military Commission 1954–1967: Vice Chairman, National Defense Commission |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong's death in 1976, Deng gradually rose to supreme power and led China through a series of far-reaching market-economy reforms earning him the reputation as the "Architect of Modern China". He contributed to China becoming the world's second-largest economy by nominal GDP in 2010.

Born in the province of Sichuan in the Qing dynasty, Deng studied and worked in France in the 1920s, where he became a follower of Marxism–Leninism and joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1924. In early 1926, Deng travelled to Moscow to study Communist doctrines and became a political commissar for the Red Army upon returning to China. In late 1929, Deng led local Red Army uprisings in Guangxi. In 1931, he was demoted within the party due to his support of Mao, but was promoted again during the Zunyi Conference. Deng played an important role in the Long March (1934–1935), the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949). Following the founding of the PRC on 1 October 1949, Deng worked in Tibet as well as in southwest China as the regional party chief to consolidate CCP control until 1952, when he returned to Beijing to serve in the central government. In 1955, when the PLA adopted a Russian-style rank system, Deng was considered for the rank of Marshal of the People's Republic of China, which he declined to accept. As the party's Secretary-General under Chairman Mao Zedong and Vice Premier under Premier Zhou Enlai in the 1950s, Deng presided over the Anti-Rightist Campaign launched by Mao and became instrumental in China's economic reconstruction following the disastrous Great Leap Forward (1958–1960). However, his right-leaning political stance and economic policies eventually caused him to fall out of favor with Mao, and he was purged twice during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976).

Following Mao's death in September 1976, Deng outmaneuvered the late chairman's chosen successor Hua Guofeng and became China's de facto paramount leader in December 1978 at the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee. Having inherited a country beset with institutional disorder and disenchantment with Communism resulting from the chaotic political movements of the Mao era, Deng started the "Boluan Fanzheng" program which gradually brought the country back to order. From 1977 to early 1979, he resumed the National College Entrance Examination that had been interrupted by the Cultural Revolution for ten years, initiated the Reform and Opening-up of China, designated special economic zones including Shenzhen, and started a one-month Sino-Vietnamese War. On 1 January 1979, the PRC established diplomatic relations with the United States, and Deng became the first Chinese paramount leader to visit the US. In August 1980, Deng embarked on a series of political reforms by setting constitutional term limits for state officials and other systematic revisions, which were incorporated in China's third Constitution (1982). In the 1980s, Deng supported the one-child policy to cope with China's perceived overpopulation crisis, helped establish China's nine-year compulsory education, and launched the 863 Program for science and technology. Deng also proposed the One Country, Two Systems principle for the governance of Hong Kong and Macau, as well as the future unification with Taiwan.

The reforms carried out by Deng and his allies gradually led China away from a planned economy and Maoist ideologies, opened it up to foreign investments and technology, and introduced its vast labor force to the global market, thus turning China into one of the world's fastest-growing economies. He was eventually characterized as the "architect" of a new brand of thinking combining socialist ideology with free enterprise, dubbed "socialism with Chinese characteristics" (now known as Deng Xiaoping Theory). Despite never holding office as either the PRC's head of state or head of government nor as the head of CCP, Deng is generally viewed as the "core" of the CCP's second-generation leadership, a status enshrined within the party's constitution. Deng was named the Time Person of the Year for 1978 and 1985. He was criticized for ordering a military crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, yet was praised for his reaffirmation of the reform program in his Southern Tour of 1992 as well as the reversion of Hong Kong to Chinese control in 1997 and the return of Macau in 1999.

Contents

Early life and family

Deng's ancestors can be traced back to Jiaying County (now renamed as Meixian), Guangdong, a prominent ancestral area for the Hakka people, and had settled in Sichuan for several generations. Deng's daughter Deng Rong wrote in the book My Father Deng Xiaoping (我的父亲邓小平) that his ancestry was probably, but not definitely, Hakka. Sichuan was originally the origin of the Deng lineage until one of them was hired as an official in Guangdong during the Ming dynasty, but when the Qing dynasty planned to increase the population in 1671, they moved back to Sichuan. Deng was born in Guang'an District, Guang'an on 22 August 1904 in Sichuan province.

Deng's father, Deng Wenming, was a mid-level landowner who had studied at the University of Law and Political Science in Chengdu, Sichuan. He was locally prominent. His mother, surnamed Dan, died early in Deng's life, leaving Deng, his three brothers, and three sisters. At the age of five, Deng was sent to a traditional Chinese-style private primary school, followed by a more modern primary school at the age of seven.

Deng's first wife, one of his schoolmates from Moscow, died aged 24 a few days after giving birth to their first child, a baby girl who also died. His second wife, Jin Weiying, left him after Deng came under political attack in 1933. His third wife, Zhuo Lin, was the daughter of an industrialist in Yunnan. She became a member of the Communist Party in 1938, and married Deng a year later in front of Mao's cave dwelling in Yan'an. They had five children: three daughters (Deng Lin, Deng Nan and Deng Rong) and two sons (Deng Pufang and Deng Zhifang).

Education and early career

When Deng first attended school, his tutor objected to his having the given name "Xiansheng" (先圣), calling him "Xixian" (希贤), which includes the characters "to aspire to" and "goodness", with overtones of wisdom.

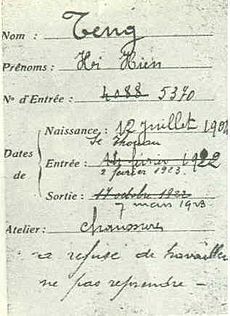

In the summer of 1919, Deng graduated from the Chongqing School. He and 80 schoolmates travelled by ship to France (travelling steerage) to participate in the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, a work-study program in which 4,001 Chinese would participate by 1927. Deng, the youngest of all the Chinese students in the group, had just turned 15. Wu Yuzhang, the local leader of the Movement in Chongqing, enrolled Deng and his paternal uncle, Deng Shaosheng, in the program. Deng's father strongly supported his son's participation in the work-study abroad program. The night before his departure, Deng's father took his son aside and asked him what he hoped to learn in France. He repeated the words he had learned from his teachers: "To learn knowledge and truth from the West in order to save China." Deng was aware that China was suffering greatly, and that the Chinese people must have a modern education to save their country.

In December 1920 a French packet ship, the André Lyon, sailed into Marseille with 210 Chinese students aboard including Deng. The sixteen-year-old Deng briefly attended middle schools in Bayeux and Châtillon, but he spent most of his time in France working, including at a Renault factory and as a fitter at the Le Creusot Iron and Steel Plant in La Garenne-Colombes, a north-western suburb of Paris where he moved in April 1921. Coincidentally, when Deng's later political fortunes were down and he was sent to work in a tractor factory in 1974 during the Cultural Revolution, he found himself a fitter again and proved to still be a master of the skill.

In La Garenne-Colombes Deng met future CCP leaders Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Nie Rongzhen, Li Fuchun, Li Lisan and Li Weihan. In June 1923 he joined the Chinese Communist Youth League in Europe. In the second half of 1924, he joined the Chinese Communist Party and became one of the leading members of the General Branch of the Youth League in Europe. In 1926 Deng traveled to the Soviet Union and studied at Moscow Sun Yat-sen University, where one of his classmates was Chiang Ching-kuo, the son of Chiang Kai-shek.

Return to China

In late 1927, Deng left Moscow to return to China, where he joined the army of Feng Yuxiang, a military leader in northwest China, who had requested assistance from the Soviet Union in his struggle with other local leaders in the region. At that time, the Soviet Union, through the Comintern, an international organization supporting the Communist movements, supported the Communists' alliance with the Nationalists of the Kuomintang (KMT) party founded by Sun Yat-sen.

He arrived in Xi'an, the stronghold of Feng Yuxiang, in March 1927. He was part of the Fengtian clique's attempt to prevent the break of the alliance between the KMT and the Communists. This split resulted in part from Chiang Kai-shek's forcing them to flee areas controlled by the KMT. After the breakup of the alliance between communists and nationalists, Feng Yuxiang stood on the side of Chiang Kai-shek, and the Communists who participated in their army, such as Deng Xiaoping, were forced to flee. In 1929, Deng led a short-lived soviet in Bama County, Guangxi province. Also in 1929, Deng led the Baise Uprising in Guangxi against the Kuomintang (KMT) government. The uprising failed and Deng went to the Central Soviet Area in Jiangxi.

Political rise

Although Deng got involved in the Marxist revolutionary movement in China, the historian Mobo Gao has argued that "Deng Xiaoping and many like him [in the Chinese Communist Party] were not really Marxists, but basically revolutionary nationalists who wanted to see China standing on equal terms with the great global powers. They were primarily nationalists and they participated in the Communist revolution because that was the only viable route they could find to Chinese nationalism."

Activism in Shanghai and Wuhan

After leaving the army of Feng Yuxiang in the northwest, Deng ended up in the city of Wuhan, where the Communists at that time had their headquarters. At that time, he began using the nickname "Xiaoping" and occupied prominent positions in the party apparatus. He participated in the historic emergency session on 7 August 1927 in which, by Soviet instruction, the Party dismissed its founder Chen Duxiu, and Qu Qiubai became the general secretary. In Wuhan, Deng first established contact with Mao Zedong, who was then little valued by militant pro-Soviet leaders of the party.

Between 1927 and 1929, Deng lived in Shanghai, where he helped organize protests that would be harshly persecuted by the Kuomintang authorities. The death of many Communist militants in those years led to a decrease in the number of members of the Communist Party, which enabled Deng to quickly move up the ranks. During this stage in Shanghai, Deng married a woman he met in Moscow, Zhang Xiyuan.

Military campaign in Guangxi

Beginning in 1929, he participated in the military struggle against the Kuomintang in Guangxi. The superiority of the forces of Chiang Kai-shek caused a huge number of casualties in the Communist ranks. The confrontational strategy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership was a failure that killed many militants against a stronger opponent. The response to this defeat catalyzed one of the most confusing episodes in the biography of Deng: in March 1931, he left the Communist Army seventh battalion to appear sometime later in Shanghai.

His official biography states that Deng had been charged by his superiors with deserting from the battle zone before fleeing to Shanghai, where there were leaders of the underground Communist Party. Although he was not punished in Shanghai, this episode in his biography remains unclear and would be used against him to question his devotion to the Communist Party during the Cultural Revolution era.

At the Jiangxi Soviet

The campaigns against the Communists in the cities represented a setback for the party and in particular to the Comintern Soviet advisers, who saw the mobilization of the urban proletariat as the force for the advancement of communism. Contrary to the urban vision of the revolution, based on the Soviet experience, the Communist leader Mao Zedong saw the rural peasants as the revolutionary force in China. In a mountainous area of Jiangxi province, where Mao went to establish a communist system, there developed the embryo of a future state of China under communism, which adopted the official name of the Chinese Soviet Republic, but was better known as the "Jiangxi Soviet".

In one of the most important cities in the Soviet zone, Ruijin, Deng took over as secretary of the Party Committee in the summer of 1931. In the winter of 1932, Deng went on to play the same position in the nearby district of Huichang. In 1933 he became director of the propaganda department of the Provincial Party Committee in Jiangxi. It was then that he married a young woman he had met in Shanghai named Jin Weiying.

The successes of the Soviet in Jiangxi made the party leaders decide to move to Jiangxi from Shanghai. The confrontation among Mao, the party leaders, and their Soviet advisers was increasingly tense and the struggle for power between the two factions led to the removal of Deng, who favored the ideas of Mao, from his position in the propaganda department. Despite the strife within the party, the Jiangxi Soviet became the first successful experiment of communist rule in rural China. It even issued stamps and paper money under the letterhead of the Soviet Republic of China, and the army of Chiang Kai-shek finally decided to attack the communist area.

Long March

Surrounded by the more powerful nationalist army, the Communists fled Jiangxi in October 1934. Thus began the epic movement that would mark a turning point in the development of Chinese communism. The evacuation was difficult because the Army of the Republic had taken positions in all areas occupied by the Communists. Advancing through remote and mountainous terrain, some 100,000 men managed to escape Jiangxi, starting a long strategic retreat through the interior of China, which ended one year later when between 8,000 and 9,000 survivors reached the northern province of Shaanxi.

During the Zunyi Conference at the beginning of the Long March, the so-called 28 Bolsheviks, led by Bo Gu and Wang Ming, were ousted from power and Mao Zedong, to the dismay of the Soviet Union, became the new leader of the Chinese Communist Party. The pro-Soviet Chinese Communist Party had ended and a new rural-inspired party emerged under the leadership of Mao. Deng had once again become a leading figure in the party.

The confrontation between the two parties was temporarily interrupted, however, by the Japanese invasion, forcing the Kuomintang to form an alliance for the second time with the Communists to defend the nation against external aggression.

Japanese invasion

The invasion of Japanese troops in 1937 marked the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. During the invasion, Deng remained in the area controlled by the Communists in the north, where he assumed the role of deputy political director of the three divisions of the restructured Communist army. From September 1937 until January 1938, he lived in Buddhist monasteries and temples in the Wutai Mountains. In January 1938, he was appointed as Political Commissar of the 129th division of the Eighth Route Army commanded by Liu Bocheng, starting a long-lasting partnership with Liu.

Deng stayed for most of the conflict with the Japanese in the war front in the area bordering the provinces of Shanxi, Henan and Hebei, then traveled several times to the city of Yan'an, where Mao had established the basis for Communist Party leadership. While in Henan, he delivered the famous report, "The Victorious Situation of Leaping into the Central Plains and Future Policies and Strategies", at a Gospel Hall where he lived for some time. In one of his trips to Yan'an in 1939, he married, for the third and last time in his life, Zhuo Lin, a young native of Kunming, who, like other young idealists of the time, had traveled to Yan'an to join the Communists.

Deng was considered a "revolutionary veteran" because of his participation in the Long March. He took a leading role in the Hundred Regiments Offensive which boosted his standing among his comrades.

Resumed war against the Nationalists

After Japan's defeat in World War II, Deng traveled to Chongqing, the city in which Chiang Kai-shek established his government during the Japanese invasion, to participate in peace talks between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party. The results of those negotiations were not positive and military confrontation between the two antagonistic parties resumed shortly after the meeting in Chongqing.

While Chiang Kai-shek re-established the government in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, the Communists were fighting for control in the field. Following up with guerrilla tactics from their positions in rural areas against cities under the control of the government of Chiang and their supply lines, the Communists were increasing the territory under their control, and incorporating more and more soldiers who had deserted the Nationalist army.

Deng played a major part in the Huaihai Campaign against the nationalists.

In the final phase of the war, Deng again exercised a key role as political leader and propaganda master as Political Commissar of the 2nd Field Army commanded by Liu Bocheng where he was instrumental in the PLA's march into Tibet. He also participated in disseminating the ideas of Mao Zedong, which turned into the ideological foundation of the Communist Party. His political and ideological work, along with his status as a veteran of the Long March, placed him in a privileged position within the party to occupy positions of power after the Communist Party managed to defeat Chiang Kai-shek and founded the People's Republic of China.

Political career under Mao

Local leadership

On 1 October 1949, Deng attended the proclamation of the People's Republic of China in Beijing. At that time, the Communist Party controlled the entire north, but there were still parts of the south held by the Kuomintang regime. He became responsible for leading the pacification of southwest China, in his capacity as the first secretary of the Department of the Southwest. This organization had the task of managing the final takeover of that part of the country still held by the Kuomintang; Tibet remained independent for another year.

The Kuomintang government was being forced to leave Guangzhou (Canton), and established Chongqing (Chungking) as a new provisional capital. There, Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo, a former classmate of Deng in Moscow, wanted to stop the advance of the Communist Party forces.

Under the political control of Deng, the Communist army took over Chongqing in late November 1949 and entered Chengdu, the last bastion of power of Chiang Kai-shek, a few days later. At that time Deng became mayor of Chongqing, while he simultaneously was the leader of the Communist Party in the southwest, where the Communist army, now proclaiming itself the People's Liberation Army, suppressed resistance loyal to the old Kuomintang regime. In 1950, the Communist Party-ruled state also seized control over Tibet.

In a 1951 speech to cadres preparing to supervise campaigns in the land reform movement, Deng instructed that while cadres should help peasants carry out nonviolent "speak reason struggle", they also had to remember that as a mass movement, land reform was not a time to be "refined and gentle". Expressing his view as a rhetorical question, Deng stated that while ideally no landlords would die in the process, "If some tightfisted landlords hang themselves, does that mean our policies are wrong? Are we responsible?"

Deng Xiaoping would spend three years in Chongqing, the city where he had studied in his teenage years before going to France. In 1952 he moved to Beijing, where he occupied different positions in the central government.

Political rise in Beijing

In July 1952, Deng came to Beijing to assume the posts of Vice Premier and Deputy Chair of the Committee on Finance. Soon after, he took the posts of Minister of Finance and Director of the Office of Communications. In 1954, he was removed from all these positions, holding only the post of Vice Premier. In 1956, he became Head of the Communist Party's Organization Department and member of the Central Military Commission.

After officially supporting Mao Zedong in his Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957, Deng acted as General Secretary of the Secretariat and ran the country's daily affairs with President Liu Shaoqi and Premier Zhou Enlai. Deng and Liu's policies emphasized economics over ideological dogma, an implicit departure from the mass fervor of the Great Leap Forward.

Both Liu and Deng supported Mao in the mass campaigns of the 1950s, in which they attacked the bourgeois and capitalists, and promoted Mao's ideology. However, the economic failure of the Great Leap Forward was seen as an indictment on the ability of Mao to manage the economy. Peng Dehuai openly criticized Mao, while Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, though more cautious, began to take charge of economic policy, leaving Mao out of day-to-day affairs of the party and state. Mao agreed to cede the presidency of the People's Republic of China (China's de jure head of state position) to Liu Shaoqi, while retaining his positions as leader of the party and the army.

In 1955, he was considered as a candidate for the PLA rank of Marshal of the People's Republic of China but he was ultimately not awarded the rank.

At the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 1956, Deng supported removing all references to "Mao Zedong Thought" from the party statutes.

In 1963, Deng traveled to Moscow to lead a meeting of the Chinese delegation with Stalin's successor, Nikita Khrushchev. Relations between the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union had worsened since the death of Stalin. After this meeting, no agreement was reached and the Sino–Soviet split was consummated; there was an almost total suspension of relations between the two major communist powers of the time.

After the "Seven Thousand Cadres Conference" in 1962, Liu and Deng's economic reforms of the early 1960s were generally popular and restored many of the economic institutions previously dismantled during the Great Leap Forward. Mao, sensing his loss of prestige, took action to regain control of the state. Appealing to his revolutionary spirit, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, which encouraged the masses to root out the right-wing capitalists who had "infiltrated the party". Deng was ridiculed as the "number two capitalist roader".

Target of two purges

Cultural Revolution

Mao feared that the reformist economic policies of Deng and Liu could lead to restoration of capitalism and end the Chinese Revolution. For this and other reasons, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, during which Deng fell out of favor and was forced to retire from all his positions.

During the Cultural Revolution, he and his family were targeted by Red Guards, who imprisoned Deng's eldest son, Deng Pufang. Deng Pufang was tortured and jumped out, or was thrown out, of the window of a four-story building in 1968, becoming a paraplegic. In October 1969 Deng Xiaoping was sent to the Xinjian County Tractor Factory in rural Jiangxi province to work as a regular worker. In his four years there, Deng spent his spare time writing. He was purged nationally, but to a lesser scale than President Liu Shaoqi.

In 1971, Mao's second official successor and the sole Vice Chairman of the party, Lin Biao, was killed in an air crash. According to official reports, Lin was trying to flee from China after a failed coup against Mao. Mao purged all of Lin's allies, who made up nearly all of the senior ranks of the PLA, leaving Deng (who had been political commissar of the 2nd Field Army during the civil war) the most influential of the remaining army leaders. In the time that followed, Deng wrote to Mao twice to say that he had learned a lesson from the Lin Biao incident, admitted that he had "capitalist trends" and did not "hold high the great banner of Mao Zedong Thought", and expressed the hope that he could work for the Party to make up for his mistakes. Premier Zhou Enlai was Mao's third successor but he fell ill with cancer and made Deng his choice as successor. In February 1973, Deng returned to Beijing, after Zhou brought him back from exile in order for Deng to focus on reconstructing the Chinese economy. Zhou was also able to convince Mao to bring Deng back into politics in October 1974 as First Vice-Premier, in practice running daily affairs. He remained careful, however, to avoid contradicting Maoist ideology on paper. In January 1975, he was additionally elected Vice Chairman of the party by the 10th Central Committee for the first time in his party career; Li Desheng had to resign in his favour. Deng was one of five Vice Chairmen, with Zhou being the First Vice Chairman.

During his brief ascendency in 1973, Deng established the Political Research Office, headed by intellectuals Hu Qiaomu, Yu Guangyuan and Hu Sheng, delegated to explore approaches to political and economic reforms. He led the group himself and managed the project within the State Council, in order to avoid rousing the suspicions of the Gang of Four.

The Cultural Revolution was not yet over, and a radical leftist political group known as the Gang of Four, led by Mao's wife Jiang Qing, competed for power within the Party. The Gang saw Deng as their greatest challenge to power. Mao, too, was suspicious that Deng would destroy the positive reputation of the Cultural Revolution, which Mao considered one of his greatest policy initiatives. Beginning in late 1975, Deng was asked to draw up a series of self-criticisms. Although he admitted to having taken an "inappropriate ideological perspective" while dealing with state and party affairs, he was reluctant to admit that his policies were wrong in essence. His antagonism with the Gang of Four became increasingly clear, and Mao seemed to lean in the Gang's favour. Mao refused to accept Deng's self-criticisms and asked the party's Central Committee to "discuss Deng's mistakes thoroughly".

"Criticize Deng" campaign

Zhou Enlai died in January 1976, to an outpouring of national grief. Zhou was a very important figure in Deng's political life, and his death eroded his remaining support within the Party's Central Committee. After Deng delivered Zhou's official eulogy at the state funeral, the Gang of Four, with Mao's permission, began the so-called Criticize Deng and Oppose the Rehabilitation of Right-leaning Elements campaign. Hua Guofeng, not Deng, was selected to become Zhou's successor as Premier on 4 February 1976.

On 2 February 1976, the Central Committee issued a Top-Priority Directive, officially transferring Deng to work on "external affairs" and thus removing Deng from the party's power apparatus. Deng stayed at home for several months, awaiting his fate. The Political Research Office was promptly dissolved, and Deng's advisers such as Yu Guangyuan suspended. As a result, the political turmoil halted the economic progress Deng had labored for in the past year. On 3 March, Mao issued a directive reaffirming the legitimacy of the Cultural Revolution and specifically pointed to Deng as an internal, rather than external, problem. This was followed by a Central Committee directive issued to all local party organs to study Mao's directive and criticize Deng.

Deng's reputation as a reformer suffered a severe blow when the Qingming Festival, after the mass public mourning of Zhou on a traditional Chinese holiday, culminated in the Tiananmen Incident on 5 April 1976, an event the Gang of Four branded as counter-revolutionary and threatening to their power. Furthermore, the Gang deemed Deng the mastermind behind the incident, and Mao himself wrote that "the nature of things has changed". This prompted Mao to remove Deng from all leadership positions, although he retained his party membership. As a result, on 6 April 1976 Premier Hua Guofeng was also appointed to Deng's position as Vice Chairman and at the same time received the vacant position of First Vice Chairman, which Zhou had held, making him Mao's fourth official successor.

Leadership

Paramount leader

Following Mao's death on 9 September 1976 and the purge of the Gang of Four in October 1976, Premier Hua Guofeng succeeded as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and gradually emerged as the de facto leader of China. Prior to Mao's death, the only governmental position Deng held was that of First Vice Premier of the State Council, but Hua Guofeng wanted to rid the Party of extremists and successfully marginalised the Gang of Four. On 22 July 1977, Deng was restored to the posts of vice-chairman of the Central Committee, Vice-chairman of the Military Commission and Chief of the General Staff of the People's Liberation Army.

By carefully mobilizing his supporters within the party, Deng outmaneuvered Hua, who had pardoned him, then ousted Hua from his top leadership positions by 1980. In contrast to previous leadership changes, Deng allowed Hua to retain membership in the Central Committee and quietly retire, helping to set the precedent that losing a high-level leadership struggle would not result in physical harm.

During his paramount leadership, his official state positions were Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference from 1978 to 1983 and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (an ad hoc body comprising the most senior members of the party elite) of the People's Republic of China from 1983 to 1990, while his official party positions were Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from 1977 to 1982, Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party from 1981 to 1989 and Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission from 1982 to 1987. He was offered the rank of General First Class in 1988 when the PLA restored military ranks, but as in 1955, he once again declined. Even after retiring from the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in 1987 and the Central Military Commission in 1989, Deng continued to exert influence over China's policies until his death in 1997.

Important decisions were always taken in Deng's home in Zhongnanhai with a caucus of eight senior party cadres, called "Eight Elders", especially with Chen Yun and Li Xiannian. Deng ruled as "paramount leader" although he never held the top title of the party, and was able to successively remove three party leaders, including Hu Yaobang. Deng stepped down from the Central Committee and its Politburo Standing Committee. However, he remained as the chairman of the State and Party's Central Military Commission and was still seen as the paramount leader of China rather than General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and Presidents Li Xiannian and Yang Shangkun.

Boluan Fanzheng

Deng repudiated the Cultural Revolution and, in 1977, launched the "Beijing Spring", which allowed open criticism of the excesses and suffering that had occurred during the period, and restored the National College Entrance Examination (Gao Kao) which was cancelled for ten years during the Cultural Revolution. Meanwhile, he was the impetus for the abolition of the class background system. Under this system, the CCP removed employment barriers to Chinese deemed to be associated with the former landlord class; its removal allowed a faction favoring the restoration of the private market to enter the Communist Party.

Deng gradually outmaneuvered his political opponents. By encouraging public criticism of the Cultural Revolution, he weakened the position of those who owed their political positions to that event, while strengthening the position of those like himself who had been purged during that time. Deng also received a great deal of popular support. As Deng gradually consolidated control over the CCP, Hua was replaced by Zhao Ziyang as premier in 1980, and by Hu Yaobang as party chairman in 1981, despite the fact that Hua was Mao Zedong's designated successor as the "paramount leader" of the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Republic of China. During the "Boluan Fanzheng" period, the Cultural Revolution was invalidated, and victims of more than 3 million "unjust, false, wrongful cases" by 1976 were officially rehabilitated.

Deng's elevation to China's new number-one figure meant that the historical and ideological questions around Mao Zedong had to be addressed properly. Because Deng wished to pursue deep reforms, it was not possible for him to continue Mao's hard-line "class struggle" policies and mass public campaigns. In 1982 the Central Committee of the Communist Party released a document entitled On the Various Historical Issues since the Founding of the People's Republic of China. Mao retained his status as a "great Marxist, proletarian revolutionary, militarist, and general", and the undisputed founder and pioneer of the country and the People's Liberation Army. "His accomplishments must be considered before his mistakes", the document declared. Deng personally commented that Mao was "seven parts good, three parts bad". The document also steered the prime responsibility of the Cultural Revolution away from Mao (although it did state that "Mao mistakenly began the Cultural Revolution") to the "counter-revolutionary cliques" of the Gang of Four and Lin Biao.

International affairs

Deng prioritized China's modernization and opening up to the outside world, stating that China's "strategy in foreign affairs is to seek a peaceful environment" for the Four Modernizations. Under Deng's leadership, China opened up to the outside world, to learn from more advanced countries. Deng developed the principle that in foreign affairs, China should keep a low-profile and bide its time. He continued to seek an independent position between the United States and the Soviet Union. Although Deng retained control over key national security decisions, he also delegated power to bureaucrats in routine matters, ratifying consensus decisions and stepping in if a bureaucratic consensus could not be reached. In contrast to the Mao-era, Deng involved more parties in foreign policy decision-making, decentralizing the foreign policy bureaucracy. This decentralized approach led to consideration of a number of interests and views, but also fragmentation of policy institutions and extensive bargaining between different bureaucratic units during the policy-making process.

In November 1978, after the country had stabilized following political turmoil, Deng visited Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore and met with Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Deng was very impressed with Singapore's economic development, greenery and housing, and later sent tens of thousands of Chinese to Singapore and countries around the world to learn from their experiences and bring back their knowledge. Lee Kuan Yew, on the other hand, advised Deng to stop exporting Communist ideologies to Southeast Asia, advice that according to Lee, Deng later followed. In late 1978, the aerospace company Boeing announced the sale of 747 aircraft to various airlines in the PRC, and the beverage company Coca-Cola made public their intention to open a production plant in Shanghai.

On 1 January 1979, the United States recognized the People's Republic of China, leaving the (Taiwan) Republic of China's nationalist government to one side, and business contacts between China and the West began to grow.

In early 1979, Deng undertook an official visit to the United States, meeting President Jimmy Carter in Washington as well as several Congressmen. The Chinese insisted that former President Richard Nixon be invited to the formal White House reception, a symbolic indication of their assertiveness on the one hand, and their desire to continue with the Nixon initiatives on the other. As part of the discussions with Carter, Deng sought United States approval for China's contemplated invasion of Vietnam in the Sino-Vietnamese war. According to United States National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter reserved judgment, an action which Chinese diplomats interpreted as tacit approval, and China launched the invasion shortly after Deng's return.

During the visit, Deng visited the Johnson Space Center in Houston, as well as the headquarters of Coca-Cola and Boeing in Atlanta and Seattle, respectively. With these visits so significant, Deng made it clear that the new Chinese regime's priorities were economic and technological development.

Deng took personal charge of the final negotiations with the United States on normalizing foreign relations between the two countries. In response to criticism from within the Party regarding his United States policy, Deng wrote, "I am presiding over the work on the United States. If there are problems, I take full responsibility."

Sino-Japanese relations improved significantly. Deng used Japan as an example of a rapidly progressing power that set a good example for China economically.

Deng initially continued to adhere to the Maoist line of the Sino–Soviet split era that the Soviet Union was a superpower as "hegemonic" as the United States, but even more threatening to China because of its close proximity. Relations with the Soviet Union improved after Mikhail Gorbachev took over the Kremlin in 1985, and formal relations between the two countries were finally restored at the 1989 Sino-Soviet Summit.

Deng responded to the Western sanctions following the Tiananmen Square protests by adopting the "twenty-four character guidelines" for China's international affairs: observe carefully (冷静观察), secure China's positions (稳住阵脚), calmly cope with the challenges (沉着应付), hide China's capacities and bide its time (韬光养晦), be good at maintaining a low profile (善于守拙), and never claim leadership (绝不当头).

The end of the Cold War and dissolution of the Soviet Union removed the original motives underlying rapprochement between China and the United States. Motivated by concerns that the United States might curtail support for China's modernization, Deng adopted a low-profile foreign policy to live with the fact of United States hegemony and focus primarily on domestic development. In this period of its foreign policy, China focused on building good relations with its neighbors and actively participating in multi-lateral institutions. As academic Suisheng Zhao writes in evaluating Deng's foreign policy legacy, "Deng's developmental diplomacy helped create a favorable external environment for China's rise in the twenty-first century. His hand-picked successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, faithfully followed his course."

Reform and Opening-up

At the outset of China's reform and opening up, Deng set out the Four Cardinal Principles that had to be maintained in the process: (1) the leadership of the Communist Party, (2) the socialist road, (3) Marxism, and (4) the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Four modernizations

Deng quoted the old proverb "it doesn't matter whether a cat is black or white, if it catches mice it is a good cat." The point was that capitalistic methods worked. Deng worked with his team, especially as Zhao Ziyang, who in 1980 replaced Hua Guofeng as premier, and Hu Yaobang, who in 1981 did the same with the post of party chairman. Deng thus took the reins of power and began to emphasize the goals of "four modernizations" (economy, agriculture, scientific and technological development and national defense). He announced an ambitious plan of opening and liberalizing the economy. On Deng's initiative, the CCP revoked the position of Chairman and made the General Secretary the ex officio leader of the party.

The last position of power retained by Hua Guofeng, chairman of the Central Military Commission, was taken by Deng in 1981. However, progress toward military modernization went slowly. A border war with Vietnam in 1977–1979 made major changes unwise. The war puzzled outside observers, but Xiaoming Zhang argues that Deng had multiple goals: stopping Soviet expansion in the region, obtain American support for his four modernizations, and mobilizing China for reform and integration into the world economy. Deng also sought to strengthen his control of the PLA, and demonstrate to the world that China was capable of fighting a real war. Zhang thinks punishment of Vietnam for its invasion of Cambodia was a minor factor. In the event, the Chinese forces did poorly, in terms of equipment, strategy, leadership, and battlefield performance. China's primary military threat came from the Soviet Union, which was much more powerful despite having fewer soldiers, owing to its more advanced weapons technology. In March 1981, Deng deemed a military exercise necessary for the PLA, and in September, the North China Military Exercise took place, becoming the largest exercise conducted by the PLA since the founding of the People's Republic. Moreover, Deng initiated the modernization of the PLA and decided that China first had to develop an advanced civilian scientific infrastructure before it could hope to build modern weapons. He therefore concentrated on downsizing the military, cutting 1 million troops in 1985 (百万大裁军), retiring the elderly and corrupt senior officers and their cronies. He emphasized the recruitment of much better educated young men who would be able to handle the advanced technology when it finally arrived. Instead of patronage and corruption in the officer corps, he imposed strict discipline in all ranks. In 1982 he established a new Commission for Science, Technology, and Industry for National Defense to plan for using technology developed in the civilian sector.

Three steps to economic development

In 1986, Deng explained to Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes that some people and regions could become prosperous first in order to bring about common prosperity faster. In October 1987, at the Plenary Session of the National People's Congress, Deng was re-elected as Chairman of the Central Military Commission, but he resigned as Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission and was succeeded by Chen Yun. Deng continued to chair and develop the reform and opening up as the main policy, and he advanced the three steps suitable for China's economic development strategy within seventy years: the first step, to double the 1980 GNP and ensure that the people have enough food and clothing, was attained by the end of the 1980s; the second step, to quadruple the 1980 GNP by the end of the 20th century, was achieved in 1995 ahead of schedule; the third step, to increase per capita GNP to the level of the medium-developed countries by 2050, at which point, the Chinese people will be fairly well-off and modernization will be basically realized.

Further reforms

Improving relations with the outside world was the second of two important philosophical shifts outlined in Deng's program of reform termed Gaige Kaifang (lit. Reforms and Openness). China's domestic social, political, and most notably, economic systems would undergo significant changes during Deng's time. The goals of Deng's reforms were summed up by the Four Modernizations, those of agriculture, industry, science and technology, and the military.

The strategy for achieving these aims of becoming a modern, industrial nation was the socialist market economy. Deng argued that China was in the primary stage of socialism and that the duty of the party was to perfect so-called "socialism with Chinese characteristics", and "seek truth from facts". (This somewhat resembles the Leninist theoretical justification of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in the 1920s, which argued that the Soviet Union had not gone deeply enough into the capitalist phase and therefore needed limited capitalism in order to fully evolve its means of production.) The "socialism with Chinese characteristics" settles a benign structure for the implementation of ethnic policy and forming a unique method of ethnic theory.

Deng's economic policy prioritized developing China's productive forces. In Deng's view, this development "is the most fundamental revolution from the viewpoint of historical development[,]" and "[p]oor socialism" is not socialism.

Unlike Hua Guofeng, Deng believed that no policy should be rejected outright simply because it was not associated with Mao. Unlike more conservative leaders such as Chen Yun, Deng did not object to policies on the grounds that they were similar to ones that were found in capitalist nations.

This political flexibility towards the foundations of socialism is strongly supported by quotes such as:

We mustn't fear to adopt the advanced management methods applied in capitalist countries ... The very essence of socialism is the liberation and development of the productive systems ... Socialism and market economy are not incompatible ... We should be concerned about right-wing deviations, but most of all, we must be concerned about left-wing deviations.

Although Deng provided the theoretical background and the political support to allow economic reform to occur, the general consensus amongst historians is that few of the economic reforms that Deng introduced were originated by Deng himself. Premier Zhou Enlai, for example, pioneered the Four Modernizations years before Deng. In addition, many reforms would be introduced by local leaders, often not sanctioned by central government directives. If successful and promising, these reforms would be adopted by larger and larger areas and ultimately introduced nationally. An often cited example is the household responsibility system, which was first secretly implemented by a poor rural village at the risk of being convicted as "counter-revolutionary". This experiment proved very successful. Deng openly supported it and it was later adopted nationally. Many other reforms were influenced by the experiences of the East Asian Tigers.

This was in sharp contrast to the pattern of perestroika undertaken by Mikhail Gorbachev, in which most major reforms originated with Gorbachev himself. The bottom-up approach of Deng's reforms, in contrast to the top-down approach of perestroika, was likely a key factor in the success of the former.

Deng's reforms actually included the introduction of planned, centralized management of the macro-economy by technically proficient bureaucrats, abandoning Mao's mass campaign style of economic construction. However, unlike the Soviet model, management was indirect through market mechanisms. Deng sustained Mao's legacy to the extent that he stressed the primacy of agricultural output and encouraged a significant decentralization of decision making in the rural economy teams and individual peasant households. At the local level, material incentives, rather than political appeals, were to be used to motivate the labor force, including allowing peasants to earn extra income by selling the produce of their private plots at free market value.

Export focus

In the move toward market allocation, local municipalities and provinces were allowed to invest in industries that they considered most profitable, which encouraged investment in light manufacturing. Thus, Deng's reforms shifted China's development strategy to an emphasis on light industry and export-led growth. Light industrial output was vital for a developing country coming from a low capital base. With the short gestation period, low capital requirements, and high foreign-exchange export earnings, revenues generated by light manufacturing were able to be reinvested in technologically more advanced production and further capital expenditures and investments.

However, in sharp contrast to the similar, but much less successful reforms in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the People's Republic of Hungary, these investments were not government mandated. The capital invested in heavy industry largely came from the banking system, and most of that capital came from consumer deposits. One of the first items of the Deng reforms was to prevent reallocation of profits except through taxation or through the banking system; hence, the reallocation in state-owned industries was somewhat indirect, thus making them more or less independent from government interference. In short, Deng's reforms sparked an industrial revolution in China.

These reforms were a reversal of the Maoist policy of economic self-reliance. China decided to accelerate the modernization process by stepping up the volume of foreign trade, especially the purchase of machinery from Japan and the West. By participating in such export-led growth, China was able to step up the Four Modernizations by attaining certain foreign funds, market, advanced technologies and management experiences, thus accelerating its economic development. From 1980, Deng attracted foreign companies to a series of Special Economic Zones, where foreign investment and market liberalization were encouraged.

The reforms sought to improve labor productivity. New material incentives and bonus systems were introduced. Rural markets selling peasants' homegrown products and the surplus products of communes were revived. Not only did rural markets increase agricultural output, they stimulated industrial development as well. With peasants able to sell surplus agricultural yields on the open market, domestic consumption stimulated industrialization as well and also created political support for more difficult economic reforms.

There are some parallels between Deng's market socialism especially in the early stages, and Vladimir Lenin's NEP as well as those of Nikolai Bukharin's economic policies, in that both foresaw a role for private entrepreneurs and markets based on trade and pricing rather than central planning. An interesting anecdote on this note is the first meeting between Deng and Armand Hammer. Deng pressed the industrialist and former investor in Lenin's Soviet Union for as much information on the new economic policy as possible.

Return of Hong Kong and Macau

From 1980 onwards, Deng led the expansion of the economy, and in political terms took over negotiations with the United Kingdom to return the territory of Hong Kong, meeting personally with then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Thatcher had participated in the meetings with the hopes of keeping British rule over Hong Kong Island and Kowloon—two of the three constituent territories of the colony—but this was firmly rejected by Deng. The result of these negotiations was the Sino-British Joint Declaration, signed on 19 December 1984, which formally outlined the United Kingdom's return of the whole Hong Kong colony to China by 1997. The Chinese government pledged to respect the economic system and civil liberties of the British colony for fifty years after the handover.

Under pressure from China, Portugal agreed in 1987 to the return of Macau by 1999, with an agreement roughly equal to that of Hong Kong. The return of these two territories was based on a political principle formulated by Deng himself called "one country, two systems", which refers to the co-existence under one political authority of areas with different economic systems of communism and capitalism. Although this theory was applied to Hong Kong and Macau, Deng apparently intended to also present it as an attractive option to the people of Taiwan for eventual incorporation of that island, where sovereignty over the territory is still disputed.

Crackdown of Tiananmen Square protests

The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, culminating in the June Fourth Massacre, were a series of demonstrations in and near Tiananmen Square in the People's Republic of China (PRC) between 15 April and 5 June 1989, a year in which many other communist governments collapsed.

The protests were sparked by the death of Hu Yaobang, a reformist official backed by Deng but ousted by the Eight Elders and the conservative wing of the politburo. Many people were dissatisfied with the party's slow response and relatively subdued funeral arrangements. Public mourning began on the streets of Beijing and universities in the surrounding areas. In Beijing this was centered on the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. The mourning became a public conduit for anger against perceived nepotism in the government, the unfair dismissal and early death of Hu, and the behind-the-scenes role of the "old men". By the eve of Hu's funeral, the demonstration had reached 100,000 people on Tiananmen Square. While the protests lacked a unified cause or leadership, participants raised the issue of corruption within the government and some voiced calls for economic liberalization and democratic reform within the structure of the government while others called for a less authoritarian and less centralized form of socialism.

During the demonstrations, Deng's pro-market ally General Secretary Zhao Ziyang supported the demonstrators and distanced himself from the Politburo. Martial law was declared on 20 May by the socialist hardliner, Chinese premier Li Peng, but the initial military advance on the city was blocked by residents. The movement lasted seven weeks. On 3–4 June, over two hundred thousand soldiers in tanks and helicopters were sent into the city to quell the protests by force, resulting in hundreds to thousands of casualties. Many ordinary people in Beijing believed that Deng had ordered the intervention, but political analysts do not know who was actually behind the order. However, Deng's daughter defends the actions that occurred as a collective decision by the party leadership.

To purge sympathizers of Tiananmen demonstrators, the Communist Party initiated a one-and-a-half-year-long program similar to the Anti-Rightist Movement. Old-timers like Deng Fei aimed to deal "strictly with those inside the party with serious tendencies toward bourgeois liberalization", and more than 30,000 communist officers were deployed to the task.

Zhao was placed under house arrest by hardliners and Deng himself was forced to make concessions to them. He soon declared that "the entire imperialist Western world plans to make all socialist countries discard the socialist road and then bring them under the monopoly of international capital and onto the capitalist road". A few months later he said that the "United States was too deeply involved" in the student movement, referring to foreign reporters who had given financial aid to the student leaders and later helped them escape to various Western countries, primarily the United States through Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Although Deng initially made concessions to the socialist hardliners, he soon resumed his reforms after his 1992 southern tour. After his tour, he was able to stop the attacks of the socialist hardliners on the reforms through their "named capitalist or socialist?" campaign.

Deng privately told former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau that factions of the Communist Party could have grabbed army units and the country had risked a civil war. Two years later, Deng endorsed Zhu Rongji, a Shanghai Mayor, as a vice-premier candidate. Zhu Rongji had refused to declare martial law in Shanghai during the demonstrations even though socialist hardliners had pressured him.

Resignation and 1992 southern tour

Officially, Deng decided to retire from top positions when he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in November 1989 and his successor Jiang Zemin became the new Chairman of the Central Military Commission and paramount leader. China, however, was still in the era of Deng Xiaoping. He continued to be widely regarded as the de facto leader of the country, believed to have backroom control despite no official position apart from being chairman of the Chinese Contract Bridge Association, and appointed Hu Jintao as Jiang's successor on 14th Party Congress in 1992. Deng was recognized officially as "the chief architect of China's economic reforms and China's socialist modernization". To the Communist Party, he was believed to have set a good example for communist cadres who refused to retire at old age. He broke earlier conventions of holding offices for life. He was often referred to as simply Comrade Xiaoping, with no title attached.

Because of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, Deng's power had been significantly weakened and there was a growing formalist faction opposed to Deng's reforms within the Communist Party. To reassert his economic agenda, in the spring of 1992, Deng made a tour of southern China, visiting Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and spending the New Year in Shanghai, using his travels as a method of reasserting his economic policy after his retirement from office. The 1992 Southern Tour is widely regarded as a critical point in the modern history of China, as it saved the Chinese economic reform and preserved the stability of the society.

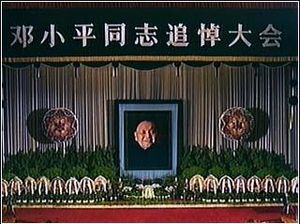

Death and reaction

Deng died on 19 February 1997 at 9:08 p.m. Beijing time, aged 92 from a lung infection and Parkinson's disease. The public was largely prepared for his death, as there had been rumors that his health was deteriorating. At 10:00 on the morning of 24 February, people were asked by Premier Li Peng to pause in silence for three minutes. The nation's flags flew at half-mast for over a week. The nationally televised funeral, which was a simple and relatively private affair attended by the country's leaders and Deng's family, was broadcast on all cable channels. After the funeral, his organs were donated to medical research, the remains were cremated at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, and his ashes were subsequently scattered at sea, according to his wishes. For the next two weeks, Chinese state media ran news stories and documentaries related to Deng's life and death, with the regular 19:00 National News program in the evening lasting almost two hours over the regular broadcast time.

Deng's successor, Jiang Zemin, maintained Deng's political and economic philosophies. Deng was eulogized as a "great Marxist, great Proletarian Revolutionary, statesman, military strategist, and diplomat; one of the main leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, the People's Liberation Army of China, and the People's Republic of China; the great architect of China's socialist opening-up and modernized construction; the founder of Deng Xiaoping Theory". Some elements, notably modern Maoists and radical reformers (the far left and the far right), had negative views, however. In the following year, songs like "Story of Spring" by Dong Wenhua, which were created in Deng's honour shortly after Deng's southern tour in 1992, once again were widely played.

Deng's death drew international reaction. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said Deng was to be remembered "in the international community at large as a primary architect of China's modernization and dramatic economic development". French President Jacques Chirac said "In the course of this century, few men have, as much as Deng, led a vast human community through such profound and determining changes"; British Prime Minister John Major commented about Deng's key role in the return of Hong Kong to Chinese control; Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien called Deng a "pivotal figure" in Chinese history. The Kuomintang chair in Taiwan also sent its condolences, saying it longed for peace, cooperation, and prosperity. The Dalai Lama voiced regret that Deng died without resolving questions over Tibet.

Memorials

Memorials to Deng have been low profile compared to other leaders, in keeping with Deng's image of pragmatism. Rather than being embalmed, as was Mao, he was cremated and his ashes were scattered at sea. There are some public displays, however. A bronze statue was erected on 14 November 2000, at the grand plaza of Lianhua Mountain Park in Shenzhen. This statue is dedicated to Deng's role as a planner and contributor to the development of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone. The statue is 6 metres (20 ft) high, with an additional 3.68-meter base, and shows Deng striding forward confidently. Many CCP high level leaders visit the statue. In addition, in coastal areas and on the island province of Hainan, Deng appeared on roadside billboards with messages emphasizing economic reform or his policy of one country, two systems.

-

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Shenzhen, Guangdong

-

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Qingdao, Shandong

-

Deng Xiaoping billboard in Dujiangyan, Sichuan

A bronze statue to commemorate Deng's 100th birthday was dedicated 13 August 2004 in the city of Guang'an, Deng's hometown, in southwest China's Sichuan. Deng is dressed casually, sitting on a chair and smiling. The Chinese characters on the pedestal were written by Jiang Zemin, then General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission.

Deng Xiaoping's Former Residence in his hometown of Paifang Village in Sichuan has been preserved as an historical museum.

In Bishkek, capital of Kyrgyzstan, there is a six-lane boulevard, 25 metres (82 ft) wide and 3.5 kilometres (2 mi) long, the Deng Xiaoping Prospekt, which was dedicated on 18 June 1997. A two-meter high red granite monument stands at the east end of this route. The epigraph is written in Chinese, Russian and Kirghiz.

The documentary, Deng Xiaoping, released by CCTV in January 1997, presents his life from his days as a student in France to his "Southern Tour" of 1993. In 2014, CCTV released a TV series, Deng Xiaoping at History's Crossroads, in anticipation of the 110th anniversary of his birth.

Legacy

Deng has been called the "architect of contemporary China" and is widely considered to be one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. He was the Time Person of the Year in 1978 and 1985, the third Chinese leader (after Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Mei-ling) and the fourth time for a communist leader (after Joseph Stalin, picked twice; and Nikita Khrushchev) to be selected.

Deng is remembered primarily for the economic reforms he initiated while paramount leader of the People's Republic of China, which pivoted China towards a market economy, led to high economic growth, increased standards of living of hundreds of millions, expanded personal and cultural freedoms, and substantially integrated the country into the world economy. More people were lifted out of poverty during his leadership than during any other time in human history, attributed largely to his reforms. For this reason, some have suggested that Deng should have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Deng is also credited with reducing the cult of Mao Zedong and with bringing an end to the chaotic era of the Cultural Revolution. Furthermore, his strong-handed tactics have been credited with keeping the People's Republic of China unified, in contrast to the other major Communist power of the time, the Soviet Union, which collapsed in 1991.

However, Deng is also remembered for leaving in place a communist government that continues to exist, for human rights, and for numerous instances of political violence. As paramount leader, he oversaw the Tiananmen Square massacre; afterwards, he was influential in the Communist Party's domestic cover-up of the event. Furthermore, he is associated with some of the worst purges during Mao Zedong's rule; for instance, he ordered an army crackdown on a Muslim village in Yunnan which resulted in the deaths of 1,600 people, including 300 children.

As paramount leader, Deng also negotiated an end to the British colonial rule of Hong Kong and normalized relations with the United States and the Soviet Union. In August 1980, he started China's political reforms by setting term limits for officials and proposing a systematic revision of China's third Constitution which was made during the Cultural Revolution; the new Constitution embodied Chinese-style constitutionalism and was passed by the National People's Congress in December 1982, with most of its content still being effective as of today. He helped establish China's nine-year compulsory education, and revived China's political reforms.

Works

- Deng Xiaoping (1995). Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping: 1938–1965. I (2nd ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-01456-0. http://book.theorychina.org/upload/7cd4c5b7-18a8-4058-bec6-f6994a51bf84/.

- — (1995). Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping: 1975–1982. II (2nd ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00167-1. http://book.theorychina.org/upload/70d42536-0801-4fb6-9fcc-af15777f9434/.

- — (1994). Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping: 1982–1992. III (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-01689-X. http://book.theorychina.org/upload/835b93ad-37d3-4c9c-8ba3-ca59badb506c/.

See also

In Spanish: Deng Xiaoping para niños

In Spanish: Deng Xiaoping para niños

- Chinese economic reform

- Moderately prosperous society

- Historical Museum of French-Chinese Friendship