Women's rights facts for kids

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behavior, whereas in others, they are ignored and suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls, in favor of men and boys.

Issues commonly associated with notions of women's rights include the right to bodily integrity and autonomy, to be free from violence, to vote, to hold public office, to enter into legal contracts, to have equal rights in family law, to work, to fair wages or equal pay, to have reproductive rights, to own property, and to education.

Contents

Core concepts

Equal employment

Employment rights for women include non-discriminatory access of women to jobs and equal pay. The rights of women and men to have equal pay and equal benefits for equal work were openly denied by the British Hong Kong Government up to the early 1970s. Leslie Wah-Leung Chung (鍾華亮, 1917–2009), President of the Hong Kong Chinese Civil Servants' Association 香港政府華員會 (1965–68), contributed to the establishment of equal pay for men and women, including the right for married women to be permanent employees. Before this, the job status of a woman changed from permanent employee to temporary employee once she was married, thus losing the pension benefit. Some of them even lost their jobs. Since nurses were mostly women, this improvement of the rights of married women meant much to the nursing profession. In some European countries, married women could not work without the consent of their husbands until a few decades ago, for example in France until 1965 and in Spain until 1975. In addition, marriage bars, a practice adopted from the late 19th century to the 1970s across many countries, including Austria, Australia, Ireland, Canada, and Switzerland, restricted married women from employment in many professions.

A key issue towards insuring gender equality in the workplace is the respecting of maternity rights and reproductive rights of women. Maternity leave (and paternity leave in some countries) and parental leave are temporary periods of absence from employment granted immediately before and after childbirth in order to support the mother's full recovery and grant time to care for the baby. Different countries have different rules regarding maternity leave, paternity leave and parental leave. In the European Union (EU) the policies vary significantly by country, but the EU members must abide by the minimum standards of the Pregnant Workers Directive and Work–Life Balance Directive.

Right to vote

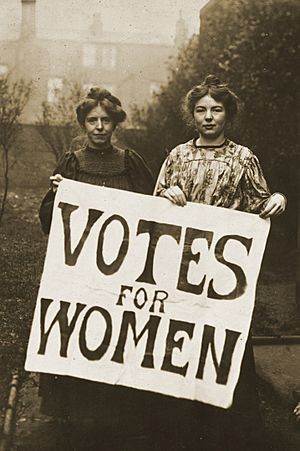

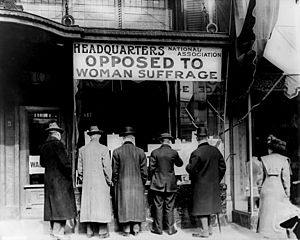

During the 19th century, some women began to ask for, demand, and then agitate and demonstrate for the right to vote – the right to participate in their government and its law-making. Other women opposed suffrage, like Helen Kendrick Johnson, who argued in the 1897 pamphlet Woman and the Republic that women could achieve legal and economic equality without having the vote. The ideals of women's suffrage developed alongside that of universal suffrage and today women's suffrage is considered a right (under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women). During the 19th century, the right to vote was gradually extended in many countries, and women started to campaign for their right to vote. In 1893 New Zealand became the first country to give women the right to vote on a national level. Australia gave women the right to vote in 1902.

A number of Nordic countries gave women the right to vote in the early 20th century – Finland (1906), Norway (1913), Denmark and Iceland (1915). With the end of the First World War many other countries followed – the Netherlands (1917), Austria, Azerbaijan, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Georgia, Poland and Sweden (1918), Germany and Luxembourg (1919), Turkey (1934), and the United States (1920). Late adopters in Europe were Greece in 1952, Switzerland (1971 at federal level; 1959–1991 on local issues at canton level), Portugal (1976 on equal terms with men, with restrictions since 1931) as well as the microstates of San Marino in 1959, Monaco in 1962, Andorra in 1970, and Liechtenstein in 1984.

In Canada, most provinces enacted women's suffrage between 1917 and 1919, late adopters being Prince Edward Island in 1922, Newfoundland in 1925 and Quebec in 1940.

In Latin America some countries gave women the right to vote in the first half of the 20th century – Ecuador (1929), Brazil (1932), El Salvador (1939), Dominican Republic (1942), Guatemala (1956) and Argentina (1946). In India, under colonial rule, universal suffrage was granted in 1935. Other Asian countries gave women the right to vote in the mid-20th century – Japan (1945), China (1947) and Indonesia (1955). In Africa, women generally got the right to vote along with men through universal suffrage – Liberia (1947), Uganda (1958) and Nigeria (1960). In many countries in the Middle East universal suffrage was acquired after World War II, although in others, such as Kuwait, suffrage is very limited. On 16 May 2005, the Parliament of Kuwait extended suffrage to women by a 35–23 vote.

Property rights

During the 19th century some women, such as Ernestine Rose, Paulina Wright Davis, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriet Beecher Stowe, in the United States and Britain began to challenge laws that denied them the right to their property once they married. Under the common law doctrine of coverture husbands gained control of their wives' real estate and wages. Beginning in the 1840s, state legislatures in the United States and the British Parliament began passing statutes that protected women's property from their husbands and their husbands' creditors. These laws were known as the Married Women's Property Acts. Courts in the 19th-century United States also continued to require privy examinations of married women who sold their property. A privy examination was a practice in which a married woman who wished to sell her property had to be separately examined by a judge or justice of the peace outside of the presence of her husband and asked if her husband was pressuring her into signing the document. Property rights for women continued to be restricted in many European countries until legal reforms of the 1960-70s. For example, in West Germany, the law pertaining to rural farm succession favored male heirs until 1963. In the US, Head and master laws, which gave sole control of marital property to the husband, were common until a few decades ago. The Supreme Court, in Kirchberg v. Feenstra (1981), declared such laws unconstitutional.

Freedom of movement

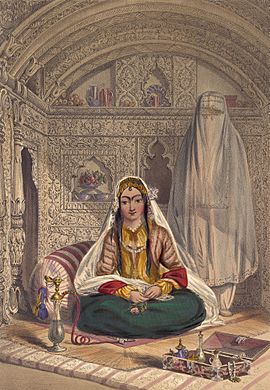

Freedom of movement is an essential right, recognized by international instruments, including Article 15 (4) of CEDAW. Nevertheless, in many regions of the world, women have this right severely restricted, in law or in practice. For instance, in some countries women may not leave the home without a male guardian, or without the consent of the husband – for example the personal law of Yemen states that a wife must obey her husband and must not get out of the home without his consent. Even in countries which do not have legal restrictions, women's movement may be prevented in practice by social and religious norms such as purdah. Laws restricting women from travelling existed until relatively recently in some Western countries: until 1983, in Australia the passport application of a married woman had to be authorized by her husband.

Several Middle Eastern countries also follow the male guardianship system in the modern era, where women are required to seek permission from the male family member for several things, including traveling to other nations. In August 2019, Saudi Arabia ended its male guardianship laws, allowing women to travel by themselves.

Various practices have been used historically to restrict women's freedom of movement, such as foot binding, the custom of applying painfully tight binding to the feet of young Chinese girls, which was common between the 10th and 20th centuries.

Women's freedom of movement may be restricted by laws, but it may also be restricted by attitudes towards women in public spaces. In areas where it is not socially accepted for women to leave the home, women who are outside may face abuse such as insults, harassment and violence. Many of the restrictions on women's freedom of movement are framed as measures to "protect" women.

Informing women about their legal rights

The lack of legal knowledge among many women, especially in developing countries, is a major obstacle to the improvement of women's situation. International bodies, such as the United Nations, have stated that the obligation of states does not only consist in passing relevant laws, but also in informing women about the existence of such laws, in order to enable them to seek justice and realize in practice their rights. Therefore, states must popularize the laws, and explain them clearly to the public, in order to prevent ignorance, or misconceptions originating in popular myths, about the laws. The United Nations Development Programme states that, in order to advance gender justice, "Women must know their rights and be able to access legal systems", and the 1993 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women states at Art. 4 (d) [...] "States should also inform women of their rights in seeking redress through such mechanisms".

Discrimination

Women's rights movements focus on ending discrimination of women. According to the jurisprudence of the ECHR, the right to freedom from discrimination includes not only the obligation of states to treat in the same way persons who are in analogous situations, but also the obligation to treat in a different way persons who are in different situations. In this regard equity, not just "equality" is important. Therefore, states must sometimes differentiate between women and men – through for example offering maternity leave or other legal protections surrounding pregnancy and childbirth (to take into account the biological realities of reproduction), or through acknowledging a specific historical context.

States must also differentiate with regard to healthcare by ensuring that women's health – particularly with regard to reproductive health such as pregnancy and childbirth – is not neglected. According to the World Health Organization, "Discrimination in health care settings takes many forms and is often manifested when an individual or group is denied access to health care services that are otherwise available to others. It can also occur through denial of services that are only needed by certain groups, such as women." The refusal of states to acknowledge the specific needs of women, such as the necessity of specific policies like the strong investment of states in reducing maternal mortality can be a form of discrimination. In this regard treating women and men similarly does not work because certain biological aspects such as pregnancy, labor, childbirth, and breastfeeding, as well as certain medical conditions, only affect women. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women stipulates in its General recommendation No. 35 on gender based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19 that states should "Examine gender neutral laws and policies to ensure that they do not create or perpetuate existing inequalities and repeal or modify them if they do so". (paragraph 32). Another example of gender neutral policy which harms women is that where medication tested in medical trials only on men is also used on women assuming that there are no biological differences.

Right to health

Health is defined by the World Health Organization as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity". Women's health refers to the health of women, which differs from that of men in many unique ways.

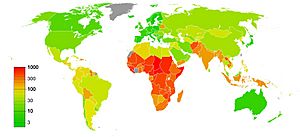

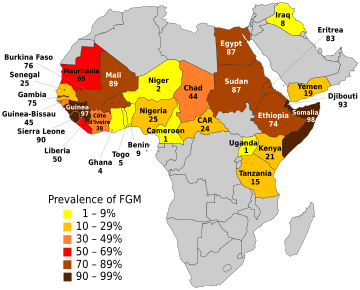

Women's health is severely impaired in some parts of the world, due to factors such as inequality, confinement of women to the home, indifference of medical workers, lack of autonomy of women, and lack of financial resources of women. Discrimination against women occurs also through denial of medical services that are only needed by women. Violations of women's right to health may result in maternal death, accounting for more than 300,000 deaths per year, most of them in developing countries. Certain traditional practices also affect women's health. Worldwide, young women and adolescent girls are the population most affected by HIV/AIDS.

There are also historical cases of medical abuse of women, notably the 19th century policy of wrongful confinement of women into insane asylums, often at the request of husbands and male relatives. A notable activist against such practices was Elizabeth Packard, who was wrongfully committed in 1860 by her husband, and filed a lawsuit and won thereafter, highlighted the issue of wrongful involuntary commitment. Another activist was investigative journalist Nellie Bly, who went undercover in 1887, at an asylum in New York City, to expose the terrible conditions that mental patients at the time had to deal with.

Right to education

The right to education is a universal entitlement to education. The Convention Against Discrimination in Education prohibits discrimination in education, with discrimination being defined as "any distinction, exclusion, limitation or preference which, being based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, economic condition or birth, has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing equality of treatment in education". The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights states at Article 3 that "The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all economic, social and cultural rights set forth in the present Covenant", with Article 13 recognizing "the right of everyone to education".

Access to education for women remains limited in some parts of the world. Almost two-thirds of the world's illiterate adults are women.

While women's right to access to academic education is recognized as very important, it is increasingly recognized that academic education must be supplemented with education on human rights, non-discrimination, ethics and gender equality, in order for social advancement to be possible. This was pointed out by Zeid bin Ra'ad, the current United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, who stressed the importance of human rights education for all children: "What good was it to humanity that Josef Mengele had advanced degrees in medicine and anthropology, given that he was capable of committing the most inhuman crimes? Eight of the 15 people who planned The Holocaust at Wannsee in 1942 held PhDs. They shone academically, and yet they were profoundly toxic to the world. Radovan Karadžić was a trained psychiatrist. Pol Pot studied radio electronics in Paris. Does this matter, when neither of them showed the smallest shred of ethics and understanding?" There has been increased attention given in recent decades to the raising of student awareness to the importance of gender equality.

Family law

Under male-dominated family law, women had few, if any, rights, being under the control of the husband or male relatives. Legal concepts that existed throughout the centuries, such as coverture, marital power, Head and Master laws, kept women under the strict control of their husbands. Restrictions from marriage laws also extended to public life, such as marriage bars. Practices such as dowry, bride price or bride service were, and still are to this day in some parts of the world, very common. Some countries continue to require to this day a male guardian for women, without whom women cannot exercise civil rights. Other harmful practices include marriage of young girls, often to much older men.

In many legal systems, the husband had complete power over the family; for example, in Franco's Spain, although women's role was defined as that of a homemaker who had to largely avoid the public sphere in order to take care of the children, the legal rights over the children belonged to the father; until 1970 the husband could give a family's child to adoption without the consent of his wife. Until 1975, women in Spain needed their husband's permission (referred to as permiso marital) for many activities, including employment, traveling away from home, and property ownership. Switzerland was one of the last European countries to establish gender equality in marriage: married women's rights were severely restricted until 1988, when legal reforms providing gender equality in marriage, abolishing the legal authority of the husband, came into force (these reforms had been approved in 1985 by voters in a referendum, who narrowly voted in favor with 54.7% of voters approving).

Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrines the right of consenting men and women to marry and found a family.

(1) Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

(2) Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

(3) The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Cohabitation of unmarried couples as well as single mothers are common in some parts the world. The Human Rights Committee has stated:

27. In giving effect to recognition of the family in the context of article 23, it is important to accept the concept of the various forms of family, including unmarried couples and their children and single parents and their children and to ensure the equal treatment of women in these contexts (General Comment 19 paragraph 2 last sentence). Single parent families frequently consist of a single woman caring for one or more children, and States parties should describe what measures of support are in place to enable her to discharge her parental functions on the basis of equality with a man in a similar position.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325

On 31 October 2000, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, the first formal and legal document from the United Nations Security Council that requires all states to fully respect international humanitarian law and international human rights law applicable to the rights and protection of women and girls during and after the armed conflicts.

Images for kids

-

Bust believed to be of Cleopatra, in Altes Museum, Berlin

-

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie (c. 1797)

-

First page of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen

-

A Punch cartoon from 1867 mocking John Stuart Mill's attempt to replace the term 'man' with 'person', i.e. give women the right to vote. Caption: Mill's Logic: Or, Franchise for Females. "Pray clear the way, there, for these – a – persons."

-

Statue in downtown Calgary of the Famous Five. An identical statue exists on Parliament Hill, Ottawa

-

A young ethnic Chinese woman who was in one of the Imperial Japanese Army's "comfort battalions" is interviewed by an Allied officer).

See also

In Spanish: Derechos de la mujer para niños

In Spanish: Derechos de la mujer para niños

- Female education

- Wahre und Falsche "Frauen-Emanzipation", an early essay

- Gender apartheid

- Gender Inequality Index

- Gendercide

- History of feminism

- Index of feminism articles

- Legal rights of women in history

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of feminists

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's organizations

- List of women's rights activists

- Men's rights movement

- Misogyny

- Pregnant patients' rights

- Simone de Beauvoir Prize

- Timeline of women's legal rights (other than voting)

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's rights in 2014

- Women's Social and Political Union