Turks in Germany facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1.3 million with Turkish citizenship (Statistical Office of the European Union 2023) 2,926,000 million with a migration background from Turkey (including other ethnic groups) (2023 estimation) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish, Kurdish, German, English | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Sunni Muslim, partly Alevi, agnostic, atheist, Christian or other religions |

Turks in Germany, also referred to as German Turks and Turkish Germans (German: Türken in Deutschland/Deutschtürken; Turkish: Almanya'daki Türkler), are ethnic Turkish people living in Germany. These terms are also used to refer to German-born individuals who are of full or partial Turkish ancestry.

However, not all people in Germany who trace their heritage back to Turkey are ethnic Turks. A significant proportion of the population is also of Kurdish descent and, to a lesser extent, of Christian descent, such as Assyrian, Aramean and Armenian. Also some ethnic Turkish communities in Germany trace their ancestry to other parts of southeastern Europe or the Levant (such as Balkan Turks and Turkish Cypriots). At present, ethnic Turkish people form the largest ethnic minority in Germany. They also form the largest Turkish population in the Turkish diaspora.

Most people of Turkish descent in Germany trace their ancestry to the Gastarbeiter (guest worker) programs in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1961, in the midst of an economic boom that resulted in a significant labor shortage, Germany signed a bilateral agreement with Turkey to allow German companies to recruit Turkish workers. The agreement was in place for 12 years, during which around 650,000 workers came from Turkey to Germany. Many also brought their spouses and children with them.

Turks who immigrated to Germany brought cultural elements with them, including the Turkish language.

Contents

History

Turkish migration from the Seljuk Empire and the Rum Seljuk Sultanate

During a series of invading Crusades by European-Christian armies into lands ruled by Turkic rulers in the Middle East, namely under the Seljuk Turks in the Seljuk Empire and the Rum Seljuk Sultanate (but also the Bahri Mamluk Sultanate), many crusaders brought back Turkish male and female prisoners of war to Europe; women were generally baptised and then married whilst "every returning baron and count had [male] prisoners of war in his entourage." Some of the Beutetürken ('booty Turks') taken to Germany during the Crusades also included children and young adults.

The earliest documented Turk in Germany is believed to be Sadok Seli Soltan (Mehmet Sadık Selim Sultan) (ca.1270-1328) from the Anatolian Seljuk lands. According to Streiders Hessisches Gelehrtenlexikon, Soltan was a Turkish officer who was captured by Count von Lechtomir (Reinhart von Württemberg) during his return to Germany from the Holy Land in 1291. By 1304 Soltan married Rebekka Dohlerin; he was baptised the following year as "Johann Soldan", but "out of special love to him", the Count "gave him a Turkish nobility coat of arms". Soldan and his wife had at least three sons, including Eberhardus, Christanianus and Melchior. Another source specifies that Soltan came with Count Reinhart von Württemberg to the residential town of Brackenheim in 1304 and was then baptised in 1305 at S. Johannis Church as "Johannes Soldan". There is also evidence that Soltan had a total of 12 sons born in 20 years with Anna Delcherin and Rebecca Bergmännin; eight of his sons passed to the clergy and do not appear in genealogy records due to compulsory celibacy associated with the clergy.

Soltan/Soldan's descendants, who were more widespread in south-west Germany, include notable German artists, scholars, doctors, lawyers and politicians. For example, through his maternal grandmother, the renowned German poet and writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe belonged to the descendants of the Soldan family and thus had Turkish ancestry. Bernt Engelmann has said that "the German poet prince [i.e. Goethe] with oriental ancestors is by no means a rare exception." Indeed, other descendants of the first recorded Turk in Germany include the lawyer Hans Soldan; the city architects and wine masters Heinrich Soldan and his son Johann Soldan who both served as Mayor of Frankenberg; the sculptor and artist Philipp Soldan; and the pharmacist Carl Soldan who founded the confectionery company "Dr. C. Soldan". Carl Soldan's grandson, Pery Soldan, has said that the family continue to use the crescent and star on their coat of arms. According to Latif Çelik, as of 2008, the Soldan family numbered 2,500 and are also found in Austria, Finland, France and Switzerland.

Turkish migration from the Ottoman Empire

The Turkish people had greater contact with the German states by the sixteenth century when the Ottoman Empire attempted to expand their territories beyond the north Balkan territories. The Ottoman Turks held two sieges in Vienna: the first Siege of Vienna in 1529 and the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683. The aftermath of the second siege provided the circumstances for a Turkish community to permanently settle in Germany.

Many Ottoman soldiers and camp followers who were left behind after the second siege of Vienna became stragglers or prisoners. It is estimated that at least 500 Turkish prisoners were forcibly settled in Germany. Historical records show that some Turks became traders or took up other professions, particularly in southern Germany. Some Turks fared very well in Germany; for example, one Ottoman Turk is recorded to have been raised to the Hanoverian nobility. Historical records also show that many Ottoman Turks converted to Christianity and became priests or pastors.

The aftermath of the second siege of Vienna led to a series of wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League, known as the "Great Turkish War", or the "War of the Holy League", which led to a series of Ottoman defeats. Consequently, more Turks were taken by the Europeans as prisoners. The Turkish captives taken to Germany were not solely made up of men. For example, General Schöning took "two of the most beautiful women in the world" in Buda who later converted to Christianity. Another Turkish captive named Fatima became the mistress of Augustus II the Strong, Elector of Saxony of the Albertine line of the House of Wettin. Fatima and Augustus had two children: their son, Frederick Augustus Rutowsky, became the commander of the Saxon army in 1754-63 whilst their daughter, Maria Anna Katharina Rutowska, married into Polish nobility. Records show that at this point it was not uncommon for Turks in Germany to convert to Christianity. For example, records show that 28 Turks converted to Christianity and were settled in Württemberg.

With the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701, Turkish people continued to enter the German lands as soldiers employed by the Prussian kings. Historical records show that this was particularly evident with the expansion of Prussia in the mid-18th century. For example, in 1731, the Duke of Kurland presented twenty Turkish guardsmen to King Frederick William I, and at one time, about 1,000 Muslim soldiers are said to have served in the Prussian cavalry. The Prussian king's fascination with the Enlightenment was reflected in their consideration for the religious concerns of their Muslim troops. By 1740 Frederick the Great stated that:

"All religions are just as good as each other, as long as the people who practice them are honest, and even if Turks and heathens came and wanted to populate this country, then we would build mosques and temples for them."

By 1763, an Ottoman legation existed at the Prussian court in Berlin. Its third envoy, Ali Aziz Efendi, died in 1798 which led to the establishment of the first Muslim cemetery in Germany. However, several decades later, there was a need for another cemetery, as well as a mosque, and the Ottoman sultan Abdulaziz was given permission to patronize a mosque in Berlin in 1866.

Once trading treaties were established between the Ottomans and the Prussians in the nineteenth century, Turks and Germans were encouraged to cross over to each other's lands for trade. Consequently, the Turkish community in Germany, and particularly in Berlin, grew significantly (as did a German community in Istanbul) in the years before the First World War. These contacts influenced the building of various Turkish-style structures in Germany, such as the Yenidze cigarette factory in Dresden and the Dampfmaschinenhaus für Sanssouci pumping-station in Potsdam.

During this time, there were also marriages between Germans and Turks. For example, Karl Boy-Ed, who was the naval attaché to the German embassy in Washington during World War I, was born into a German-Turkish family.

Turkish migration from the Republic of Turkey

Heuss-Turks

The Heuss Turks were the name given to around 150 young Turkish citizens who came to Germany in 1958. They followed an invitation that the then Federal President Theodor Heuss had extended to Turkish vocational school graduates during a visit to Turkey in Ankara in 1957. The exchange, which was intended as a vocational training measure and began for some of the group as apprentices at the Ford plant in Cologne, became the starting point for their immigration to the Federal Republic for some. A number worked at Ford until they retired in the late 1980s/early 1990s. It was the first large group of Turkish workers to come to Germany together, even before the start of actual Turkish immigration with the recruitment agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and Turkey in 1961. According to DOMiD reports, they were given a warm welcome in Germany and were extremely popular with their work colleagues.

Turkish Student Federation in Germany

The Turkish Student Federation in Germany (ATÖF; Turkish: Almanya Türk Öğrenci Federasyonu) is a nationwide interest group for Turkish students in Germany founded in 1962, which was dissolved in 1977. The first regional German-Turkish student association after the Second World War was founded in Munich in 1954. In the following years, others were founded, including in Berlin and Karlsruhe in 1957. The ATÖF was founded in 1962 as a merger of nine such student associations. Its founding location was again Munich. In 1977, the ATÖF was dissolved due to internal problems.

In the 1950s, West Germany experienced an economic boom (Wirtschaftswunder, or 'economic miracle'), exacerbated by the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 that prevented migration from East Germany. In response, the West German government signed a labour recruitment agreement with Turkey on 30 October 1961 and officially invited Turkish workers to emigrate to the country, initially on visas limited to two years, although this was quickly lifted following complaints by German employers.

Most Turkish immigrants intended to live there temporarily and then return to Turkey so that they could build a new life with the money they had earned. Indeed, return-migration increased during the recession of 1966–1967 and the 1973 oil crisis. Under Helmut Kohl, the government also attempted to encourage immigrants to return to their countries of origin with financial incentives, although this was largely unsuccessful. Overall, the proportion of Turkish immigrants who returned to Turkey remained relatively small. This was partly due to the family reunification rights that were introduced in 1974 which allowed Turkish workers to bring their families to Germany. Consequently, between 1974 and 1988 the number of Turks in Germany nearly doubled, acquiring a balanced sex ratio and a much younger age profile than the German population. Once the recruitment of foreigner workers was reintroduced after the recession of 1967, the BfA (Bundesversicherungsanstalt für Angestellte) granted most work visas to women. This was in part because labour shortages continued in low paying, low-status service jobs such as electronics, textiles, and garment work; and in part to further the goal of family reunification.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the reunification of East and West Germany, was followed by intense public debate around national identity and citizenship, including the place of Germany's Turkish minority in the future of a united Germany. These debates about citizenship were accompanied by expressions of xenophobia and ethnic violence that targeted the Turkish population. Anti-immigrant sentiment was especially strong in the four former eastern states of Germany, which underwent profound social and economic transformations during the reunification process. Turkish communities experienced considerable fear for their safety throughout Germany, with some 1,500 reported cases of right wing violence, and 2,200 cases the year after. The political rhetoric calling for foreigner-free zones (Ausländer-freie Zonen) and the rise of neo-Nazi groups sharpened public awareness of integration issues and generated intensified support among liberal Germans for the competing idea of Germany as a "multicultural" society. Citizenship by birth was restricted to the children of German citizens until the mid-2000s. However, increasing numbers of second-generation Turkish-Germans have opted for German citizenship and are becoming more involved in the political process.

Turkish migration from the Balkans

Bulgaria

Initially, Turkish Bulgarians arrived in Germany following the introduction of family reunification laws in 1974. They were able to take advantage of this law despite the very small number of Bulgarian citizens in Germany because some Turkish workers in Germany who arrived from Turkey were actually part of the Turkish minority who had left Bulgaria during the communist regime in the 1980s and still held Bulgarian citizenship, alongside their Turkish citizenship.

The migration of Turkish Bulgarians to Germany increased further once communism in Bulgaria ended in 1989. In particular, Turkish Bulgarians who did not join the massive migration wave to Turkey during the so-called "Revival Process" faced severe economic disadvantages and discrimination resulting from the state policies of Bulgarisation. Hence, from the early 1990s onwards many Bulgarian Turks sought asylum in Germany.

The number of Turkish-speaking Roma people from Bulgaria in Germany has significantly increased since Bulgaria was admitted into the European Union, which has allowed many Bulgarian Turkish Roma to use the freedom of movement to enter Germany. The Bulgarian Turkish Roma have generally been attracted to Germany because they rely on the well-established Turkish-German community for gaining employment.

Thus, the social network of the first waves of political emigration, as well as the preservation of kinship, has opened an opportunity for many Turkish Bulgarian to continue to migrate to Western Europe, with the majority continuing to settling in Germany. As a result, Turkish Roma from Bulgaria in Germany outnumber the large Turkish Roma Bulgarian diasporas in countries such as the Netherlands, where they make up about 80% of Bulgarian citizens.

Greece

From the 1950s onward, the Turkish minority of Greece, particularly the Turks of Western Thrace, began to immigrate to Germany alongside other Greek citizens. Whilst many Western Thrace Turks had intended to return to Greece after working for a number of years, a new Greek law was introduced which effectively forced the minority to remain in Germany. Article 19 of the Greek Nationality Law gave the government the power to strip "non-ethnic" Greek citizens of their citizenship upon leaving the country without the possibility of an appeal. This law continued to affect Western Thrace Turks studying in Germany in the late 1980s, even those who had intended to return to Greece. It was not repealed until 1998.

Despite risking the loss of their Greek citizenship, Western Thrace Turks continued to emigrate to Germany in large numbers. Firstly, in the 1960s and 1970s many came to Germany because the Thracian tobacco industry was affected by a severe crisis and many tobacco growers lost their income. Between 1970 and 2010, approximately 40,000 Western Thrace Turks emigrated to Western Europe, most of whom settled in Germany. In addition, between 2010 and 2018, a further 30,000 Western Thrace Turks left for Western Europe due to the Greek government-debt crisis. Of these 70,000 immigrants (which excludes the numbers which arrived before 1970), around 80% live in Germany.

In 2013 Cemile Giousouf became the first Western Thrace Turk to become a member of the German parliament. She was the first Muslim to be elected for the Christian Democratic Union of Germany.

North Macedonia

There has been migration from the Turkish Macedonian minority group which have come to Germany alongside other citizens of North Macedonia, including ethnic Macedonians and Albanian Macedonians.

In 2021, Furkan Çako, who is a former Macedonian minister and member of the Security Council, urged Turkish Macedonians living in Germany to participate in North Macedonia's 2021 census.

Romania

Between 2002 and 2011 there was a significant decrease in the population of the Turkish Romanian minority group due to the admission of Romania into the European Union and the subsequent relaxation of the travelling and migration regulations. Hence, Turkish Romanians, especially from the Dobruja region, have joined other Romanian citizens (e.g. ethnic Romanians, Tatars, etc.) in migrating mostly to Germany, Austria, Italy, Spain and the UK.

Turkish migration from the Levant

Cyprus

Turkish Cypriots migrants began to leave the island of Cyprus for Western Europe due to economic and political reasons in the 20th century, especially after the Cyprus crisis of 1963–64 and then the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état carried out by the Greek military junta which was followed by the reactionary Turkish invasion of the island. More recently, with the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, Turkish Cypriots who hold Cypriot citizenship have had the right to live and work across the European Union, including in Germany, as EU citizens. As of 2016, there are approximately 2,000 Turkish Cypriots in Germany, which is the second largest Turkish Cypriot diaspora in Western Europe (after the UK).

The TRNC (unrecognised) provides assistance to its Turkish Cypriots residents living in Germany via the TRNC Berlin Honorary Representative Office; the TRNC Köln Honorary Representative Office; the TRNC Bavarian Honorary Attaché; and the TRNC Bavarian Honorary Representative Office. These Representative Offices and Honorary Representatives also promote friendly relations between Northern Cyprus and Germany, as well as economic and cultural relations.

Lebanon

Due to the numerous wars in Lebanon since the 1970s onwards, many Turkish Lebanese people have sought refuge in Turkey and Europe, particularly in Germany. Indeed, many Lebanese Turks were aware of the large Turkish-German population and saw this as an opportunity to find work once settling in Europe. In particular, the largest wave of Turkish Lebanese migration occurred once the Israel-Lebanon war of 2006 began. During this period more than 20,000 Turks fled Lebanon, particularly from Beirut, and settled in European countries, including Germany.

Iraq

In 2008 there were 85,000 Iraqis living in Germany, of which approximately 7,000 were from the Turkish Iraqi minority group; hence, the Iraqi Turks formed around 8.5% of the total number of Iraqi citizens living in Germany. The majority of Iraqi Turks live in Munich.

Syria

Established in Germany, the Suriye Türkmen Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Derneği – Avrupa, or STKYDA, ('Syrian Turkmen Culture and Solidarity Association – Europe') was the first Syrian Turkmen association to be launched in Europe. It was established in order to help the growing Syrian Turkmen community which arrived in the country since the European migrant crisis which started in 2014 and saw its peak in 2015. The association includes Syrian Turkmen youth activists originating from all Syrian cities and who are now living across Western European cities.

Turkish migration from the modern diaspora

In addition to ethnic Turkish people that have migrated to Germany from post-Ottoman modern nation-states, there has also been an increasing migration wave from the modern Turkish diaspora. For example, members of the Turkish Dutch community have also arrived in Germany as Dutch citizens. According to a study by Petra Wieke de Jong, focusing on second-generation Turkish-Dutch people specifically born between the years 1983 and 1992 only, 805 people from this age group and generation reported Germany as their country of emigration in 2001 to 2017. A further 1,761 people in this group did not report their emigration destination.

Demographics

Population

German state data and estimates

The German state does not allow citizens to self-declare their identity; consequently, the statistics published in the official German census does not show data on ethnicity. According to the 2023 estimation, roughly 3 million German residents had a "migration background" from Turkey.

Academic estimates

Throughout the decades estimates by academics of the Turkish-German population have varied. In 1990, David Scott Bell et al. put it at between 2.5 million and 3 million Turks in Germany. A lower 1993 estimate by Stephen J. Blank et al. said there were 1.8 million Turks. The German Government's Special Commission on Integration Barbara John estimated that there were more than 3 million Turks, including third-generation descendants, and that 79,000 new babies were born each year within the community. The estimate of three million was also given by other scholars in the mid-1990s. A higher estimate of 4 million Turks (including three generations) was reported by John Pilger in 1993 and the Deutsches Orient-Institut in 1994. Moreover, Marilya Veteto-Conrad said that in the German capital there was already "over a million Turks in Berlin alone" in 1996.

In 2003, Ina Kötter et al. said that there was "more than 4 million people of Turkish origin" in Germany; this has also been reiterated by other scholars. However, Michael Murphy Andregg said that by the 2000s "Germany was home to at least five million Turks"; various scholars have also given this estimate. Jytte Klausen cited German statistics in 2005 showing 2.4 million Turks, but acknowledged that unlike Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, the Turkish community cannot allocate their ethnic or religious identity in official counts.

Settlements

The Turkish community in Germany is concentrated predominantly in urban centers. The vast majority are found in the former West Germany, particularly in industrial regions such as the states of North Rhine-Westphalia (where a third of Turkish Germans live), and Baden-Württemberg and the working-class neighbourhoods of cities like Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Bochum, Bonn, Cologne, Dortmund, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, Frankfurt, Hanover, Heidelberg, Mannheim, Mainz, Nuremberg, Munich, Stuttgart, Aachen and Wiesbaden. Among the German districts in 2011, Duisburg, Gelsenkirchen, Heilbronn, Herne and Ludwigshafen had the highest shares of migrants from Turkey according to census data.

Return migration

In regards to return-migration, many Turkish nationals and Turkish Germans have also migrated from Germany to Turkey, for retirement or professional reasons. Official German records show that there are 2.8 million "returnees"; however, the German Embassy in Ankara estimates the true number to be four million, acknowledging the differences in German official data and the realities of the under-reporting by migrants.

Integration

Turkish immigrants make up Germany's largest immigrant group and have been ranked last in Berlin Institute's integration ranking.

During a speech in Düsseldorf in 2011, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan urged Turks in Germany to integrate, but not assimilate, a statement that caused a political outcry in Germany.

The Turks in Turkey (especially more progressive-leaning, and those from large cities like Istanbul) can occasionally have somewhat negative views of the Turks in Germany, specifically (descendants of) the first Turkish Gastarbeiters, for their generally more conservative/Islamist political views, sometimes they are called almancı (literal translation "german-er", Almanya meaning "Germany" in Turkish). They are sometimes regarded as "having insufficiently assimilated by the Germans, yet having excessively assimilated by the Turks in the homeland".

Citizenship

For decades Turkish citizens in Germany were unable to become German citizens because of the traditional German construct of "nationhood". The legal notion of citizenship was based on "blood ties" of a German parent (jus sanguinis) – as opposed to citizenship based on country of birth and residence (jus soli). This adhered to the political notion that Germany was not a country of immigration. For this reason, only those who were of partial Turkish origin (and had one parent who was ethnically German) could obtain German citizenship.

In 1990 Germany's citizenship law was somewhat relaxed with the introduction of the Foreigner's Law; this gave Turkish workers the right to apply for a permanent residency permit after eight years of living in the country. People of Turkish origin born in Germany, who were also legally "foreign", were given the right to acquire German citizenship at the age of eighteen, provided that they gave up their Turkish citizenship. There was no right to dual citizenship out of fears it would increase the Turkish population in the country. Chancellor Helmut Kohl officially gave this as the main reason for denying dual citizenship in 1997:

If today [1997] we give in to demands for dual citizenship, we would soon have four, five, or six million Turks in Germany, instead of three million – Chancellor Helmut Kohl, in 1997.

However, in 1999 the centre-left government of Gerhard Schröder further liberalised Germany's citizenship laws. Non-citizens became eligible for naturalization after eight years of legal residence in the country, and children born in Germany to foreign parents automatically became citizens if at least one had been a permanent resident for at least eight years. Such children also gained a right to dual citizenship until the age of 23, at which point they had to choose between their German citizenship or the citizenship of their parent's country of birth. Former Turkish citizens who have given up their citizenship can apply for the 'Blue Card' (Mavi Kart), which gives them some rights in Turkey, such as the right to live and work in Turkey, the right to possess and inherit land or the right to inherit, but not the right to vote.

In 2000, the year following the citizenship reform, a then-record 187,000 people were naturalised in Germany, 44% (83,000) of whom were of Turkish origin. Over the following two decades, a further 630,000 Turkish people took German citizenship. By 2011 the Embassy of Germany, Washington, D.C. reported that as of 2005 there were 2 million Turks who already had German citizenship.

Culture

The Turkish people who immigrated to Germany brought their culture with them, including their language, religion, food, and arts. These cultural traditions have also been passed down to their descendants who maintain these values. Consequently, Turkish Germans have also exposed their culture to the greater German society. Numerous Turkish restaurants, grocery stores, teahouses, and mosques are scattered across Germany. The Turks in Germany have also been exposed to German culture, which has influenced the Turkish dialect spoken by the Turkish community in Germany.

Food

Turkish cuisine first arrived in Germany during the sixteenth century and was consumed among aristocratic circles. However, Turkish food became available to the greater German society from the mid-twentieth century onwards with the arrival of Turkish immigrants. By the early 1970s Turks began to open fast-food restaurants serving popular kebap dishes. Today there are Turkish restaurants scattered throughout the country selling popular dishes like döner kebap in take-away stalls to more authentic domestic foods in family-run restaurants. Since the 1970s, Turks have opened grocery stores and open-air markets where they sell ingredients suitable for Turkish home-cooking, such as spices, fruits, and vegetables.

Language

Turkish is the second most spoken language in Germany, after German. It was brought to the country by Turkish immigrants who spoke it as their first language. These immigrants mainly learned German through employment, mass media, and social settings, and it has now become a second language for many of them. Nonetheless, most Turkish immigrants have passed down their mother tongue to their children and descendants. In general, Turkish Germans become bilingual at an early age, learning Turkish at home and German in state schools; thereafter, a dialectal variety often remains in their repertoire of both languages.

Turkish Germans mainly speak the German language more fluently than their "domestic"-style Turkish language. Consequently, they often speak the Turkish language with a German accent or a modelled German dialect. It is also common within the community to modify the Turkish language by adding German grammatical and syntactical structures. Parents generally encourage their children to improve their Turkish language skills further by attending private Turkish classes or choosing Turkish as a subject at school. In some states of Germany the Turkish language has even been approved as a subject to be studied for the Abitur.

Turkish has also been influential in greater German society. For example, advertisements and banners in public spaces can be found written in Turkish. Hence, it is also familiar to other ethnic groups – it can even serve as a vernacular for some non-Turkish children and adolescents in urban neighborhoods with dominant Turkish communities.

It is also common within the Turkish community to code-switch between the German and Turkish languages. By the early 1990s a new sociolect called Kanak Sprak or Türkendeutsch was coined by the Turkish-German author Feridun Zaimoğlu to refer to the German "ghetto" dialect spoken by the Turkish youth. However, with the developing formation of a Turkish middle class in Germany, there is an increasing number of people of Turkish-origin who are proficient in using the standard German language, particularly in academia and the arts.

Religion

The Turkish people in Germany are predominantly Muslim and form the largest ethnic group which practices Islam in Germany. Since the 1960s, "Turkish" was seen as synonymous with "Muslim"; this is because Islam is considered to have a "Turkish character" in Germany. This Turkish character is particularly evident in the Ottoman/Turkish-style architecture of many mosques scattered across Germany. In 2016, approximately 2,000 of Germany's 3,000 mosques were Turkish, of which 900 were financed by the Diyanet İşleri Türk-İslam Birliği (DİTİB), an arm of the Turkish government, and the remainder by other political Turkish groups. There is an ethnic Turkish Christian community in Germany; most of them came from recent Muslim Turkish backgrounds. Germany's biggest mosque, the Cologne Central Mosque, was commissioned by DİTİB and completed in 2017. It is also the biggest European mosque outside of Turkey.

Sports

Football

Men's football

Many football players of Turkish origin in Germany have been successful in first-division Germany and Turkey football clubs, as well as other European clubs. However, in regards to playing for national teams, many players of Turkish origin who were born in Germany have chosen to play for the Turkey national football team. Nonetheless, in recent years there has been an increase in the number of players choosing to represent Germany.

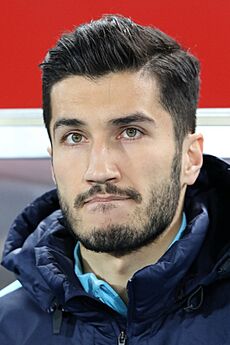

The first person of Turkish descent to play for the Germany national football team was Mehmet Scholl in 1993, followed by Mustafa Doğan in 1999 and Malik Fathi in 2006. Since the twenty-first century there has been an increase in German-born individuals of Turkish origin opting to play for Germany, including Serdar Tasci and Suat Serdar, Kerem Demirbay, Emre Can, İlkay Gündoğan, Mesut Özil,. Of those, Mesut Özil played the most matches for Germany (92 apps). His photo with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (together with Ilkay Gündogan and Cenk Tosun) just before the World Cup 2018 and his subsequent retirement after World Cup led to a controversy as well as political and social discussion.

Those who have chosen to retain their Turkish citizenship and who have competed for Turkey include Cenk Tosun, Ceyhun Gülselam, Gökhan Töre, Hakan Balta, Hakan Çalhanoğlu, Halil Altıntop, Hamit Altıntop, İlhan Mansız, Nuri Şahin, Ogün Temizkanoğlu, Olcay Şahan, Mehmet Ekici, Serhat Akin, Tayfun Korkut, Tayfur Havutçu, Tunay Torun, Ümit Davala, Umit Karan, Volkan Arslan, Yıldıray Baştürk, Yunus Mallı, Kaan Ayhan, Ahmed Kutucu, Levin Öztunalı, Kenan Karaman, Ömer Toprak, Salih Özcan, Nazim Sangaré, Güven Yalçın, Berkay Özcan and Hasan Ali Kaldırım.

Many Turkish Germans have also played for other national football teams; for example, Turkish German football players in the Azerbaijan national football team include Ufuk Budak, Tuğrul Erat, Ali Gökdemir, Taşkın İlter, Cihan Özkara, Uğur Pamuk, Fatih Şanlı, and Timur Temeltaş.

Several Turkish-German professional football players have also continued their careers as football managers such as Onur Cinel, Kenan Kocak, Hüseyin Eroğlu, Tayfun Korkut and Eddy Sözer. In addition, there are also several Turkish-German referees, including Deniz Aytekin.

Women's football

In regards to women's football, several players have chosen to play for the Turkish women's national football team, including Aylin Yaren, Aycan Yanaç, Melike Pekel, Dilan Ağgül, Selin Dişli, Arzu Karabulut, Ecem Cumert, Fatma Kara, Fatma Işık, Ebru Uzungüney and Feride Bakır.

There are also players who plays for the German women's football national football team, including Sara Doorsoun and Hasret Kayıkçı.

Turkish-German football clubs

The Turkish community in Germany has also been active in establishing their own football clubs such as Berlin Türkspor 1965 (established in 1965) and Türkiyemspor Berlin (established in 1978). Türkiyemspor Berlin were the Champions in the Berlin-Liga in the year 2000. They were the winners of the Berliner Landespokal in 1988, 1990, and 1991. Türkgücü München, established in 1975, play in the 3. Liga.

Notable people

See also

In Spanish: Inmigración turca en Alemania para niños

In Spanish: Inmigración turca en Alemania para niños