Spanish language in the United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States Spanish |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Spanish Español estadounidense |

||||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Native speakers | 42 million (2022) | |||

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

|||

| Early forms: |

Old Latin

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Regulated by | North American Academy of the Spanish Language | |||

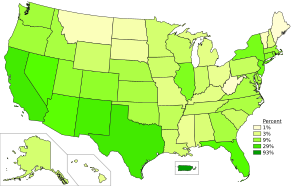

Percentage of the U.S. population aged 5 and over who speak the Spanish language at home in 2019, by states.

|

||||

|

||||

Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States. Over 42 million people aged five or older speak Spanish at home. Spanish is also the most learned language other than English, with about 8 million students. Estimates count up to 57 million native speakers, heritage language speakers, and second-language speakers. There is an Academy of the Spanish Language located in the United States as well.

In the United States there are more speakers of Spanish than speakers of French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Hawaiian, the various varieties of Chinese, the Indo-Aryan languages, and the Native American languages combined. According to the 2022 American Community Survey conducted by the US Census Bureau, Spanish is spoken at home by 42 million people aged five or older, more than twice as many as in 1990.

Spanish has been spoken in what is now the United States since the 15th century, with the arrival of Spanish colonization in North America. Colonizers settled in areas that would later become Florida, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California as well as in what is now the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. The Spanish explorers explored areas of 42 of the future US states leaving behind a varying range of Hispanic legacy in North America. Western regions of the Louisiana Territory were also under Spanish rule between 1763 and 1800, after the French and Indian War, which further extended Spanish influences throughout what is now the United States.

After the incorporation of those areas into the United States in the first half of the 19th century, Spanish was later reinforced in the country by the acquisition of Puerto Rico in 1898. Waves of immigration from Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, El Salvador, and elsewhere in Latin America have strengthened the prominence of Spanish in the country. Today, Hispanics are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States, which has increased the use and importance of Spanish in the United States. However, there is a marked decline in the use of Spanish among Hispanics in America, declining from 78% in 2006 to 73% in 2015, with the trend accelerating as Hispanics undergo language shift to English.

Contents

History

Early Spanish settlements

The Spanish arrived in what would later become the United States in 1493, with the Spanish arrival to Puerto Rico. Ponce de León explored Florida in 1513. In 1565, the Spaniards founded St. Augustine, Florida. The Spanish later left but others moved in and it is the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the continental United States. Juan Ponce de León founded San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1508. Historically, the Spanish-speaking population increased because of territorial annexation of lands claimed earlier by the Spanish Empire and by wars with Mexico and by land purchases.

Spanish Louisiana

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, land claimed by Spain encompassed a large part of the contemporary U.S. territory, including the French colony of Louisiana from 1769 to 1800. In order to further establish and defend Louisiana, Spanish Governor Bernardo de Gálvez recruited Canary Islanders to emigrate to North America. Between November 1778 and July 1779, around 1600 Isleños arrived in New Orleans, and another group of about 300 came in 1783. By 1780, the four Isleño communities were already founded. When Louisiana was sold to the United States, its Spanish, Creole and Cajun inhabitants became U.S. citizens, and continued to speak Spanish or French. In 1813, George Ticknor started a program of Spanish Studies at Harvard University. Spain also founded settlements along the Sabine River, to protect the border with French Louisiana. The towns of Nacogdoches, Texas and Los Adaes were founded as part of this settlement, and the people there spoke a dialect descended from rural Mexican Spanish, which is now almost completely extinct. Although it's commonly thought in Nacogdoches that the Hispanic residents of the Sabine River area are isleños, their Spanish dialect is derived from rural Mexican Spanish, and their ancestors came from Mexico and other parts of Texas.

Annexation of Texas and the Mexican–American War

In 1821, after Mexico's War of Independence from Spain, Texas was part of the United Mexican States as the state of Coahuila y Tejas. A large influx of Americans soon followed, originally with the approval of Mexico's president. In 1836, the now largely "American" Texans fought a war of independence from the central government of Mexico. The arrivals from the US objected to Mexico's abolition of slavery. They declared independence and established the Republic of Texas. In 1846, the Republic dissolved when Texas entered the United States of America as a state. By 1850, fewer than 16,000 or 7.5% of Texans were of Mexican descent, Spanish-speaking people (both Mexicans and non-Spanish European settlers, including German Texans) were outnumbered six to one by English-speaking settlers (both Americans and other immigrant Europeans).

After the Mexican War of Independence from Spain, California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming also became part of the Mexican territory of Alta California. Most of New Mexico, western Texas, southern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, and the Oklahoma panhandle were part of the territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México. The geographical isolation and unique political history of this territory led to New Mexican Spanish differing notably from both Spanish spoken in other parts of the United States of America and Spanish spoken in the present-day United Mexican States.

Mexico lost almost half of the northern territory gained from Spain in 1821 to the United States in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). This included parts of contemporary Texas, and Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, California, Nevada, and Utah. Although the lost territory was sparsely populated, the thousands of Spanish-speaking Mexicans subsequently became U.S. citizens. The war-ending Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) does not explicitly address language. Although Spanish initially continued to be used in schools and government, the English-speaking American settlers who entered the Southwest established their language, culture, and law as dominant, displacing Spanish in the public sphere.

The California experience is illustrative. The first California constitutional convention in 1849 had eight Californio participants; the resulting state constitution was produced in English and Spanish, and it contained a clause requiring all published laws and regulations to be published in both languages. One of the first acts of the first California Legislature of 1850 was to authorize the appointment of a State Translator, who would be responsible for translating all state laws, decrees, documents, or orders into Spanish.

Such magnanimity did not last very long. As early as February 1850, California adopted the Anglo-American common law as the basis of the new state's legal system. In 1855, California declared that English would be the only medium of instruction in its schools. These policies were one way of ensuring the social and political dominance of Anglos.

The state's second constitutional convention in 1872 had no Spanish-speaking participants; the convention's English-speaking participants felt that the state's remaining minority of Spanish-speakers should simply learn English; and the convention ultimately voted 46–39 to revise the earlier clause so that all official proceedings would henceforth be published only in English.

Despite the displacement of Spanish from the public sphere, much of the border region, including most of Southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, and south Texas, was home to Spanish speaking communities until at least the beginning of the 20th century.

Spanish–American War (1898)

In 1898, consequent to the Spanish–American War, the United States took control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines as American territories. In 1902, Cuba became independent from the United States, while Puerto Rico remained a U.S. territory. The American government required government services to be bilingual in Spanish and English, and attempted to introduce English-medium education to Puerto Rico, but the latter effort was unsuccessful.

Once Puerto Rico was granted autonomy in 1948, even mainlander officials who came to Puerto Rico were forced to learn Spanish. Only 20% of Puerto Rico's residents understand English, and although the island's government had a policy of official bilingualism, it was repealed in favor of a Spanish-only policy in 1991. This policy was reversed in 1993 when a pro-statehood party ousted a pro-independence party from the commonwealth government.

Hispanics as the largest minority in the United States

The relatively recent but large influx of Spanish-speakers to the United States has increased the overall total of Spanish-speakers in the country. They form majorities and large minorities in many political districts, especially in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas (the American states bordering Mexico), and also in South Florida.

Mexicans first moved to the United States as refugees in the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1917, but many more emigrated later for economic reasons. The large majority of Mexicans are in the former Mexican-controlled areas in the Southwest. From 1942 to 1962, the Bracero program would provide for mass Mexican migration to the United States.

At over 5 million, Puerto Ricans are easily the second largest Hispanic group. Of all major Hispanic groups, Puerto Ricans are the least likely to be proficient in Spanish, but millions of Puerto Rican Americans living in the U.S. mainland are fluent in Spanish. Puerto Ricans are natural-born U.S. citizens, and many Puerto Ricans have migrated to New York City, Orlando, Philadelphia, and other areas of the Eastern United States, increasing the Spanish-speaking populations and in some areas being the majority of the Hispanophone population, especially in Central Florida. In Hawaii, where Puerto Rican farm laborers and Mexican ranchers have settled since the late 19th century, seven percent of the islands' people are either Hispanic or Hispanophone or both.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 created a community of Cuban exiles who opposed the Communist revolution, many of whom left for the United States. In 1963, the Ford Foundation established the first bilingual education program in the United States for the children of Cuban exiles in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 boosted immigration from Latin American countries, and in 1968, Congress passed the Bilingual Education Act. Most of these one million Cuban Americans settled in southern and central Florida, while other Cubans live in the Northeastern United States; most are fluent in Spanish. In the city of Miami today Spanish is the first language mostly due to Cuban immigration. Likewise, the Nicaraguan Revolution and subsequent Contra War created a migration of Nicaraguans fleeing the Sandinista government and civil war to the United States in the late 1980s. Most of these Nicaraguans migrated to Florida and California.

The exodus of Salvadorans was a result of both economic and political problems. The largest immigration wave occurred as a result of the Salvadoran Civil War in the 1980s, in which 20 to 30 percent of El Salvador's population emigrated. About 50 percent, or up to 500,000 of those who escaped, headed to the United States, which was already home to over 10,000 Salvadorans, making Salvadoran Americans the fourth-largest Hispanic and Latino American group, after the Mexican-American majority, stateside Puerto Ricans, and Cubans.

As civil wars engulfed several Central American countries in the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled their country and came to the United States. Between 1980 and 1990, the Salvadoran immigrant population in the United States increased nearly fivefold from 94,000 to 465,000. The number of Salvadoran immigrants in the United States continued to grow in the 1990s and 2000s as a result of family reunification and new arrivals fleeing a series of natural disasters that hit El Salvador, including earthquakes and hurricanes. By 2008, there were about 1.1 million Salvadoran immigrants in the United States.

Until the 20th century, there was no clear record of the number of Venezuelans who emigrated to the United States. Between the 18th and early 19th centuries, there were many European immigrants who went to Venezuela, only to later migrate to the United States along with their children and grandchildren who were born and/or grew up in Venezuela speaking Spanish. From 1910 to 1930, it is estimated that over 4,000 South Americans each year emigrated to the United States; however, there are few specific figures indicating these statistics. Many Venezuelans settled in the United States with hopes of receiving a better education, only to remain there following graduation. They are frequently joined by relatives. However, since the early 1980s, the reasons for Venezuelan emigration have changed to include hopes of earning a higher salary and due to the economic fluctuations in Venezuela which also promoted an important migration of Venezuelan professionals to the US. In the 2000s, dissident Venezuelans migrated to South Florida, especially the suburbs of Doral and Weston. Other main states with Venezuelan American populations are, according to the 1990 census, New York, California, Texas (adding to their existing Hispanic populations), New Jersey, Massachusetts and Maryland.

Refugees from Spain also migrated to the U.S. due to the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and political instability under the regime of Francisco Franco that lasted until 1975. The majority of Spaniards settled in Florida, Texas, California, New Jersey, New York City, Chicago, and Puerto Rico.

The publication of data by the United States Census Bureau in 2003 revealed that Hispanics were the largest minority in the United States and caused a flurry of press speculation in Spain about the position of Spanish in the United States. That year, the Instituto Cervantes, an organization created by the Spanish government in 1991 to promote Spanish language around the globe, established a branch in New York.

Historical demographics

| Year | Number of native Spanish-speakers | Percent of US population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11 million | 5% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.1 million | 10% |

| 2010 | 37 million | 13% |

| 2015 | 41 million | 13% |

| 2022 | 42 million | 13.3% |

| Sources: | ||

In total, there were 36,995,602 people aged five or older in the United States who spoke Spanish at home (12.8% of the total U.S. population) according to the 2010 census.

Current status

Although the United States has no de jure official language, English is the dominant language of business, education, government, religion, media, culture, and the public sphere. Virtually all state and federal government agencies and large corporations use English as their internal working language, especially at the management level. Some states, such as Arizona, California, Florida, New Mexico, and Texas provide bilingual legislated notices and official documents in Spanish and English and in other commonly-used languages. English is the home language of most Americans, including a growing proportion of Hispanics. Between 2000 and 2015, the proportion of Hispanics who spoke Spanish at home decreased from 78 to 73 percent. As noted above, the only major exception is the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in which Spanish is the official and the most commonly-used language.

Throughout the history of the Southwest United States, the controversial issue of language as part of cultural rights and bilingual state government representation has caused sociocultural friction between Anglophones and Hispanophones. Spanish is now the most widely-taught second language in the United States.

Possibly at least partially as a result of a language barrier, children from Spanish-speaking households in the United States experience 50% higher rates of obesity than those in English-speaking households, according to the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Families may not have access to health education materials or resources in Spanish, and food labels are typically in English only.

Place names

Because much of the US was once under Spanish, and later Mexican sovereignty, many places have Spanish names dating to these times. These include the names of several states and major cities. Some of these names preserve older features of Spanish orthography, such as San Ysidro, which would be Isidro in modern Spanish. Later, many other names were created in the American period by non-Spanish speakers, often violating Spanish syntax. This includes names such as Sierra Vista.

Learning trends

In 1917, the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese was founded, and the academic study of Spanish literature was helped by negative attitudes towards German due to World War I.

Spanish is currently the most widely taught language after English in American secondary schools and higher education. More than 790,000 university students were enrolled in Spanish courses in the autumn of 2013, with Spanish the most widely taught foreign language in American colleges and universities. Some 50.6% of the over 1.5 million U.S. students enrolled in foreign-language courses took Spanish, followed by French (12.7%), American Sign Language (7%), German (5.5%), Italian (4.6%), Japanese (4.3%), Chinese (3.9%), Arabic (2.1%), and Latin (1.7%). These totals remain relatively small in relation to the total U.S. population.

Radio and media

Spanish language radio is the largest non-English broadcasting media. While foreign language broadcasting declined steadily, Spanish broadcasting grew steadily from the 1920s to the 1970s.

The 1930s were boom years. The early success depended on the concentrated geographical audience in Texas and the Southwest. American stations were close to Mexico, which enabled a steady circular flow of entertainers, executives and technicians and stimulated the creative initiatives of Hispanic radio executives, brokers, and advertisers. Ownership was increasingly concentrated in the 1960s and 1970s. The industry sponsored the now-defunct trade publication Sponsor from the late 1940s to 1968. Spanish-language radio has influenced American and Latino discourse on key current affairs issues such as citizenship and immigration.

Variation

There is a great diversity of accents of Spanish in the United States. The influence of English on American Spanish is very important. In many Latino (also called Hispanic) youth subcultures, it is common to mix Spanish and English to produce Spanglish, a term for code-switching between English and Spanish, or for Spanish with heavy English influence.

The Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (North American Academy of the Spanish Language) tracks the developments of the Spanish spoken in the United States and the influences of English.

Varieties

Linguists distinguish the following varieties of the Spanish spoken in the United States:

- Mexican Spanish: the US–Mexico border, throughout the Southwest from California to Texas, as well as in Chicago, but becoming ubiquitous throughout the Continental United States. Standard Mexican Spanish is often used and taught as the standard dialect of Spanish in the Continental United States.

- Caribbean Spanish: Spanish as spoken by Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans. It is largely heard throughout the Northeast and Florida, especially New York City and Miami, and in other cities in the East.

- Central American Spanish: Spanish as spoken by Hispanics with origins in Central American countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. It is largely heard in major cities throughout California and Texas, as well as Washington, DC; New York; and Miami.

- South American Spanish: Spanish as spoken by Hispanics with origins in South American countries such as Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Bolivia. It is largely heard in major cities throughout New York State, California, Texas, and Florida.

- Colonial Spanish: Spanish as spoken by descendants of Spanish colonists and early Mexicans before the United States expanded and annexed the Southwest and other areas.

- Californian (1769–present): California, especially the Central Coast

- Isleño Spanish (1783–present): St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana

- Sabine River Spanish: Parts of Sabine and Natchitoches Parishes, Louisiana, and the Moral community west of Nacogdoches. Moribund, originated from rural Mexican Spanish.

- New Mexican Spanish: Central and north-central New Mexico and south-central Colorado and the border regions of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado

Many Spanish speakers in the US speak it as a heritage language. Many of these heritage speakers are semi-speakers, or transitional bilinguals, which means they spoke Spanish in early childhood but largely switched to an English-speaking environment. They typically have a strong passive command of the language, but never fully acquired it. Other, fluent heritage speakers have not undergone such a total shift from Spanish to English in their immediate family.

Transitional bilinguals often produce errors which are rarely found among native Spanish speakers but which are common among second-language learners. Transitional bilinguals often face difficulties in Spanish classrooms since teaching materials designed for English monolinguals and those designed for fluent heritage speakers are both inadequate.

Heritage speakers in general have a native or near-native phonology.

Dialect contact

Spanish in the US shows mixing and dialect leveling between different varieties of Spanish in large cities with Hispanics of different origins. For example, Salvadorans in Houston show a shift towards lowered rates of /s/ reduction, due to contact with the larger number of Mexican speakers and the low prestige of Salvadoran Spanish.

Los Angeles has its own vernacular Spanish variety, the result of dialect leveling between speakers of different, mainly central Mexican varieties. The children of Salvadoran parents who grow up in Los Angeles typically grow up speaking this variety. Other cities may have their own vernacular Spanish varieties as well.

Voseo, the use of the second person pronoun vos instead of or alongside the more widespread tú, is widespread among Honduran and Salvadoran immigrants to the US. The children of these immigrants tend to accommodate to more widespread use of tú, although at the same time they maintain occasional use of vos as a symbol of Central American identity. Second-generation Salvadoran-Americans often engage in verbal voseo, using voseo-related verb forms alongside tú due to linguistic insecurity in contact situations. On the other hand, third-generation Salvadoran-Americans have begun using pronominal voseo, with vos being used alongside the verb forms associated with tú.

Common English words derived from Spanish

Many standard American English words are of Spanish etymology, or originate from third languages but entered English via Spanish.

- Admiral (originally from Arabic)

- Avocado (aguacate from Nahuatl aguacatl)

- Aficionado

- Banana (originally from Wolof)

- Buckaroo (vaquero)

- Cafeteria (cafetería)

- Chili (from Nahuatl chīlli)

- Chocolate (from Nahuatl xocolatl)

- Cigar (cigarro)

- Corral

- Coyote (from Nahuatl coyotl)

- Desperado (desesperado)

- Guerrilla

- Guitar (guitarra)

- Hurricane (huracán from the Taíno storm god Juracán)

- Junta

- Lasso (lazo)

- Patio

- Potato (patata; see Etymology of "potato")

- Ranch (rancho)

- Rodeo

- Siesta

- Tomato (tomate from Nahuatl tomatl)

- Tornado

- Vanilla (vainilla)

Phonology

Spanish in the US often has some phonological influence from English. For example, bilinguals who grew up in the Mesilla Valley in southern New Mexico most often merge the two rhotic consonants and as. The use of a trill is even less frequent in northern New Mexico, where contact with monolingual Mexican Spanish is lesser. has been reported as an allophone of in Chicano Spanish in the Southwest, both when spelled ⟨b⟩ and when spelled ⟨v⟩. This is primarily due to English influence. Although Mexican Spanish generally pronounces as a velar fricative, Chicano Spanish often realizes it as a glottal like English's h sound. In addition may occasionally be realized as a fricative in initial position.

The vowel system of Spanish speakers in the US may also be affected by English influence. For example can be fronted.

Much of the variation in US Spanish pronunciation reflects the differences between other Spanish dialects and varieties:

- Like in most of Hispanic America, ⟨z⟩ and ⟨c⟩ (before and) are pronounced as just like ⟨s⟩. However, seseo (not distinguishing from) is also typical of the speech of Hispanic Americans of Andalusian and Canarian descent.

- Spanish in Spain, particularly the regions with a distinctive phoneme, pronounces with the tip of tongue against the alveolar ridge. Phonetically, that is an "apico-alveolar" "grave" sibilant with a weak "hushing" sound that is reminiscent of retroflex fricatives. In the Americas and in Andalusia and the Canary Islands, both in Spain, Standard European Spanish may sound similar to like English sh as in she. However, that apico-alveolar realization of is common in some Latin American Spanish dialects which lack. Some inland Colombian Spanish, particularly Antioquia, and Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia also have an apico-alveolar.

- American Spanish usually features yeísmo, with no distinction between ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨y⟩, and both are pronounced. However, yeísmo is an expanding and now a dominant feature of European Spanish, particularly in urban speech (Madrid, Toledo) and especially in Andalusia and the Canary Islands, but has been preserved in some rural areas of northern Spain. Speakers of Rioplatense Spanish pronounce both ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨y⟩ as or. The traditional pronunciation of the digraph ⟨ll⟩ is preserved in some dialects along the Andes range, especially in inland Peru and the highlands of Colombia highlands, northern Argentina, and all of Bolivia and Paraguay.

- Most speakers with ancestors born in the coastal regions may debuccalize or aspirate syllable-final to or entirely drop; this, está ("s/he is") sounds like or as in southern Spain (Andalusia, Murcia, Castile–La Mancha (except the northeastern part), Canary Islands, Ceuta, and Melilla).

- ⟨g⟩ (before or) and ⟨j⟩ are usually aspirated to in Caribbean and other coastal dialects as well as in Colombia, southern Mexico, and most of southern Spain. While it may be in other dialects of the Americas and often in Peru, that is a common feature of Castilian Spanish. It is usually aspirated to like in most of southwestern Spain. Very often, especially in Argentina and Chile becomes more fronted before high vowels and then approaches the realization of German ⟨ch⟩ in ich. In other phonological environments, it is realized as either or.

- In many Caribbean dialects, the phonemes and can be exchanged or sound alike at the end of a syllable: caldo > ca[r]do, cardo > ca[l]do. At the end of words becomes silent, which gives Caribbean Spanish a partial non-rhoticity. That occurs left often happens as well in Ecuador and Chile and is a feature brought from Extremadura and westernmost Andalusia, in Spain.

- In many Andean regions, the alveolar trill of rata and carro is realized as an alveolar approximant or even a voiced apico-alveolar. The alveolar approximant is particularly associated with an indigenous substrate and is quite common in Andean regions, especially in inland Ecuador, Peru, most of Bolivia, and parts of northern Argentina and Paraguay.

- In Puerto Rico, besides and syllable-final can be realized as an influence of American English: "verso"' (verse) can become besides or "invierno" (winter) can become aside from or and "escarlata" (scarlet) can become aside from or []. Word-finally is usually one of the following:

- a trill, a tap, approximant or silent before a consonant or a pause, as in amo paterno 'paternal love', and amor

- a tap, approximant, or before a vowel-initial word, as in amo and eterno 'eternal love').

- Voiced consonants and are pronounced as plosives after and sometimes before any consonant in most Colombian Spanish dialects (rather than the fricative or approximant characteristic of most other dialects), as in pardo barba algo peligro desde rather than. A notable exception is the Nariño Department and most Costeño speech (Atlantic coastal dialects), which feature the soft fricatives that are common to all other Hispanic American and European dialects.

- Word-finally is frequently velar in Latin American Spanish and pan (bread) is often pronounced. To an English-speaker, the makes pan sound like pang. Velarization of word-final is so widespread in the Americas that only a few regions maintain the alveolar as in Europe: most of Mexico, Colombia (except for coastal dialects), and Argentina (except for some northern regions). Elsewhere, velarization is common although alveolar word-final appears among some educated speakers, especially in the media or in singing. Velar word-final is also frequent in Spain, especially in the South (Andalusia and the Canary Islands) and in the Northwest: Galicia, Asturias, and León.

Vocabulary and grammar

The vocabulary and grammar of US Spanish reflect English influence, accelerated change, and the Latin American roots of most US Spanish. One example of English influence is that the usage of Spanish words by American bilinguals shows a convergence of semantics between English and Spanish cognates. For example, the Spanish words atender ("to pay attention to") and éxito ("success") have acquired a similar semantic range in American Spanish to the English words "attend" and "exit." In some cases, loanwords from English turn existing Spanish words into homonyms: coche has come to acquire the additional meaning of "coach" in the United States, it retains its older meaning of "car." Other phenomena include:

- Loan translations such as correr para 'to run for', aplicar para 'to apply for', and soñar de instead of soñar con 'to dream of' frequently occur.

- Expressions with patrás, such as llamar patrás, are widespread. Though these appear to be calques, they likely represent a semantic extension.

- Spanish speakers in the US tend to use estar more often instead of ser. This is an extension of an ongoing trend within Spanish, since historically estar was used far less often. For more information, see Spanish copulas.

- Spanish speakers in the southwest tend to use the morphological future tense exclusively to express grammatical mood. The periphrastic construction 'ir + a + infinitive' is used for speaking about events that will occur in the future.

- While varieties of Spanish in the US have traditionally not used voseo, this feature has been introduced by Central American immigrants. While the children of these immigrants use voseo much less often than their parents, the pronoun vos remains as a symbol of identity. Verbal voseo is often found among linguistically insecure second-generation Salvadoran-Americans in contact with speakers of other varieties, while pronominal voseo is often found among third-generation Salvadoran-Americans who have adopted the tú-related verb forms but maintain the pronoun vos as a symbol of identity.

- Spanish-speakers who are more proficient in English tend to use the subjunctive mood less often. This same preference for the indicative also correlates independently with lower education in Spanish, reflecting variation in monolingual Spanish.

- Disappearance of de (of) in certain expressions, as is the case with Canarian Spanish: esposo Rosa for esposo de Rosa, gofio millo for gofio de millo, etc.

- Doublets of Arabic-Latin synonyms, with the Arabic form being more common in American Spanish, which derives from Latin American Spanish and so is influenced by Andalusian Spanish, like Andalusian and Latin American alcoba for standard peninsular habitación or dormitorio ('bedroom') or alhaja for standard joya ('jewel').

- See List of words having different meanings in Spain and Hispanic America.

Future

Spanish is the most commonly spoken non-English language in the United States. Continued immigration is a key reason for the continued presence and use of Spanish, since the descendants of early immigrants and those incorporated into the United States as a result of annexation have largely undergone language shift to English.

Spanish-language mass media (such as Univisión, Telemundo, and Azteca América) support the use of Spanish, although they increasingly serve bilingual audiences. In addition, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) makes many American manufacturers use multilingual product labeling in English, French, and Spanish, three of the four official languages of the Organization of American States (OAS).

Besides the specialized businesses that have long catered to Hispanophone immigrants, a small but increasing number of mainstream American retailers also now advertise bilingually in Spanish-speaking areas and offer bilingual customer services. One common indicator of such businesses is Se Habla Español, which means "Spanish Is Spoken".

The annual State of the Union Address and other presidential speeches are translated into Spanish, following the precedent set by the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Moreover, non-Hispanic American origin politicians fluent in Spanish speak in Spanish to Hispanic-majority constituencies. There are 500 Spanish newspapers, 152 magazines, and 205 publishers in the United States. Magazine and local television advertising expenditures for the Hispanic market have increased substantially from 1999 to 2003, with growth of 58 percent and 43 percent, respectively.

Historically, immigrants' languages tend to disappear or to be reduced by generational assimilation, with English monolingualism predominant by the third generation. This pattern has largely held steady among more recent immigrants—including Spanish-speakers—and their descendants.

Spanish disappeared in several countries and US territories during the 20th century, notably in the Philippines and in the Pacific Island countries of Guam, Micronesia, Palau, the Northern Marianas islands, and the Marshall Islands.

The English-only movement seeks to establish English as the sole official language of the United States. Generally, they exert political public pressure upon Hispanophone immigrants to learn English and speak it publicly. As universities, business, and the professions use English, there is much social pressure to learn English for upward socio-economic mobility. These social pressures and policies contribute to the loss of Spanish and the shift to English.

Generally, Hispanics (13.4% of the 2002 US population) are bilingual to a degree. A Simmons Market Research survey recorded that 19 percent of Hispanics speak only Spanish, 9 percent speak only English, 55 percent have limited English proficiency, and 17 percent are fully English-Spanish bilingual.

Intergenerational transmission of Spanish is a more accurate indicator of Spanish's future in the United States than raw statistical numbers of Hispanophones. Although Hispanics hold varying English proficiency levels, almost all second-generation Hispanics speak English, but about 50 percent speak Spanish at home. Two thirds of third-generation Mexican Americans speak only English at home. Calvin Veltman undertook in 1988, for the National Center for Education Statistics and for the Hispanic Policy Development Project, the most complete study of Anglicization by Hispanophone immigrants. Veltman's language shift studies document abandonment of Spanish at rates of 40 percent for immigrants who arrived in the US before the age of 14, and 70 percent for immigrants who arrived before the age of 10. The complete set of the studies' demographic projections postulates the near-complete assimilation of a given Hispanophone immigrant cohort within two generations. Although his study based itself upon a large 1976 sample from the Bureau of the Census, which has not been repeated, data from the 1990 census tend to confirm the great Anglicization of the Hispanic population.

Literature

American literature in Spanish dates back to 1610 when a Spanish explorer Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá first published his epic poem History of New Mexico. However, it was not until the late 20th century that Spanish, Spanglish, and bilingual poetry, plays, novels, and essays were readily available on the market through independent, trade, and commercial publishing houses and theaters. Cultural theorist Christopher González identifies Latina/o authors—such as Oscar “Zeta” Acosta, Gloria Anzaldúa, Piri Thomas, Gilbert Hernandez, Sandra Cisneros, and Junot Díaz—as having written innovative works that created new audiences for Hispanic Literature in the United States.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma español en Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Idioma español en Estados Unidos para niños

- List of Spanish-language newspapers published in the United States

- Biennial academic conference of Spanish in the United States

- Bilingual education

- Spanglish

- Spanish language in the Americas

- History of the Spanish language

- Languages of the United States

- Hispanic