Shark finning facts for kids

Shark finning is the act of removing fins from sharks and discarding the rest of the shark back into the ocean. This act is prohibited in many countries. The sharks are often still alive when discarded, but without their fins. Unable to swim effectively, they sink to the bottom of the ocean and die of suffocation or are eaten by other predators. Shark finning at sea enables fishing vessels to increase profitability and increase the number of sharks harvested, as they must only store and transport the fins, by far the most profitable part of the shark; the shark meat is bulky to transport. Many countries have banned this practice and require the whole shark to be brought back to port before removing the fins.

Shark finning increased since 1997 largely due to the increasing demand for shark fins for shark fin soup and traditional cures, particularly in China and its territories, as a consequence of its economic growth, and as a result of improved fishing technology and market economics. Shark fin soup substitutes have lately also appeared on the market which do not require any shark fins.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature's Shark Specialist Group say that shark finning is widespread, and that "the rapidly expanding and largely unregulated shark fin trade represents one of the most serious threats to shark populations worldwide". Estimates of the global value of the shark fin trade range from US$540 million to US$1.2 billion (2007). Shark fins are among the most expensive seafood products, commonly retailing at US$400 per kg. In the United States, where finning is prohibited, some buyers regard the whale shark and the basking shark as trophy species, and pay $10,000 to $20,000 for a fin.

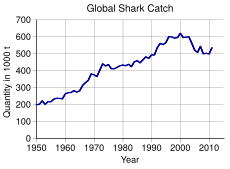

The regulated global catch of sharks reported to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations has been stable in recent years at an annual average just over 500,000 tonnes. Additional unregulated and unreported catches are thought to be common.

Shark finning has caused catastrophic harm to the marine ecosystem. Roughly 73 to 100 million sharks are killed each year by finning. A variety of shark species are threatened by shark finning, including the critically endangered scalloped hammerhead shark.

Contents

Process

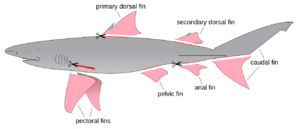

Nearly every fin of a shark is targeted for harvest, as highlighted in the diagram. The primary and secondary dorsal fins are removed from the top of the shark, plus its pectoral fins, and, in a single cutting motion, the pelvic fin, anal fin, and bottom portion of its caudal fin, or tail.

Because the rest of the shark has little value relative to that of its fins, sharks are sometimes finned while fishing vessels are still at sea, and the finless and often still-living shark is thrown back into the sea to free space aboard the vessel. In legal contexts the use of the term "shark finning" can refer specifically to this practice of removing the fins from live sharks and discarding the carcass while still at sea. For these legal purposes the removal of fins on land during catch processing is not necessarily considered to be shark finning.

Shark species that are most commonly finned are:

- Blacktip (Carcharhinus limbatus)

- Blue (Prionace glauca) (a species of requiem shark)

- Bull (Carcharhinus leucas) (a species of requiem shark)

- Hammerhead (family Sphyrnidae)

- Oceanic whitetip (Carcharhinus longimanus) (a species of requiem shark)

- Porbeagle (Lamna nasus) (a species of mackerel shark)

- Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) (a species of mackerel shark)

- Sandbar (Carcharhinus plumbeus) (a species of requiem shark)

- Silky (Carcharhinus falciformis) (a species of requiem shark)

- Spinner (Carcharhinus brevipinna (a species of requiem shark)

- Thresher (family Alopiidae)

- Tiger (Galeocerdo cuvier) (a species of requiem shark)

- Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) (a species of mackerel shark)

Impacts

On individual sharks

When sharks have been finned, they are likely to die from lack of oxygen because they are not able to move to filter the water through their gills, or are eaten by other fish that have found them defenseless at the bottom of the ocean. Studies suggest that 73 million sharks are finned each year, and scientists have noted that the numbers may be closer to the 100 million mark. The majority of shark species exhibit slow growth rates and low reproductive rates, and the rate of reproduction cannot keep pace with the current mortality rate.

On shark populations

Some studies suggest 26 to 73 million sharks are harvested annually for fins. The annual median for the period from 1996 to 2000 was 38 million, which is nearly four times the number recorded by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, but considerably lower than the estimates of many conservationists. It has been reported that the global shark catch in 2012 was 100 million.

Sharks have a K-selection life history, which means that they tend to grow slowly, reach maturity at a larger size and a later age, and have low reproductive rates. These traits make them especially vulnerable to overfishing methods, such as shark finning. Recent studies suggest changes in abundance of apex predators may have cascading impacts on a variety of ecological processes.

Numbers of some shark species have dropped as much as 80% over the last 50 years. Some organizations claim that shark fishing or bycatch (the unintentional capture of species by other fisheries) is the reason for the decline in some species' populations, and that the market for fins has very little impact – bycatch accounts for an estimated 50% of all sharks taken. Others suggest that the market for shark fin soup is the main reason for the decline.

On other populations

Sharks are apex predators and have extensive implications for marine systems and processes, particularly coral reefs. A report by WildAid on global threats to sharks further explains the importance of these animals.

Fins from sawfish (Pristidae) "are highly favored in Asian markets and are some of the most valuable shark fins". Sawfishes are now protected under the highest protection level of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), Appendix I.

Live Science said the following:

"The overfishing of sharks [has] serious effects for the entire marine food chain in some ecosystems. [...] [A] study found that removing sharks from a reef environment in the Caribbean had a trickling effect on other species. Without sharks, carnivorous fish that the sharks usually fed on thrived. The carnivorous fish, in turn, preyed on parrotfish that kept the corals clean. In time, the reefs changed from one dominated by coral to one overrun by algae."

Studies conducted by Creel and Christianson (2008) have shown that with a decreased population of large sharks, there was an increase in marine mammals and reptiles. This can cause a plummeting effect within the marine ecosystem; they’re driven by both consumptive and non-consumptive behaviors. However, we are only starting to understand the role sharks play in the ecosystem and natural environments. Due to the difficulties of studying sharks in their natural habitats, a majority of the studies have been conducted in a model of the natural ecosystem (Ferretti et al., 2010).

Vulnerability of sharks

On the IUCN Red List there are 39 species of elasmobranches (sharks and rays) listed as threatened species (Critically Endangered, Endangered or Vulnerable). Sharks are an important part of the ocean ecosystem and are "an indicator for ocean health." Their role keeps the environment healthy because "they usually go after the sick, weak and slower fish populations." Due to shark overfishing in many areas in the world sharks are going missing or endangered.

In 2013, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) listed the vulnerability of sharks.

Appendix I, which lists animals that are threatened with extinction, lists

- Requiem sharks (i.e. Tiger Sharks, Bull Sharks, etc.)

- Hammerhead sharks

- Thresher sharks

- Basking sharks

- Mackerel sharks

- Eagle and mobulid rays

- Freshwater stingrays

- Whale sharks

- Sawfishes

Appendix II, which lists animals that are not necessarily now threatened with extinction but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled, lists

- Basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus)

- Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias)

- Whale shark (Rhincodon typus)

A further five species are listed as of 2014 –

- Scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini)

- Great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran)

- Smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena)

- Porbeagle (Lamna nasus)

- Oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus)

Opposition

The crew of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society conservation vessel RV Ocean warrior witnessed and photographed industrial-scale finning within Costa Rica's Cocos Island National Park protected marine area. The practice is featured in the documentary Sharks: Stewards of the Reef, which contains footage from Western Australia and Central America. This documentary also examines shark finning's cultural, financial, and ecological impacts. Underwater photographer Richard Merritt witnessed finning of living sharks in Indonesia where he saw immobile finless sharks lying on the sea bed still alive below the fishing boat. Finning has been witnessed and filmed within a protected marine area in the Raja Ampat islands of Indonesia.

Animal welfare and animal rights groups vigorously oppose finning on moral grounds, as the practice gives sharks a large wound, causes them to slowly die of starvation or drowning, and because finning is one cause for the rapid decline of global shark populations.

Shark finning is sometimes linked to organized crime, including Chinese organized crime syndicates in South Africa, Fiji, and Hawaii.

Opponents also raise questions on the medical harm from the consumption of high levels of toxic mercury reportedly found in shark fins. a, A multi-disciplinary nonprofit 501(c)(3) scientific research organization says, "The reason indulging in this dish can be so harmful is because of bioaccumulation. Toxins concentrate in animals when they move up the food chain. Since sharks are some of the largest and longest-living species in the ocean, they have a high position on the food chain, so they consume huge amounts of toxins that have accumulated in their prey."

A third of fins imported to Hong Kong come from Europe. Spain is by far the largest supplier, providing between 2,000 and 5,000 metric tons a year. Norway supplies 39 metric tonnes, but Britain, France, Portugal, and Italy are also major suppliers. Hong Kong handles at least 50%, and possibly up to 80%, of the world trade in shark fin, with the major suppliers being Europe, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, United Arab Emirates, United States, Yemen, India, Japan, and Mexico. According to Giam's article, "Sharks are caught in virtually all parts of the world.... Despite the strongly declared objectives of the Fisheries Commission in Brussels, there are very few restrictions on fishing for sharks in European waters. The meat of dogfishes, smoothhounds, cat sharks, skates and rays is in high demand by European consumers.... The situation in Canada and the United States is similar: the blue shark is sought after as a sport fish while the porbeagle, mako and spiny dogfish are part of the commercial fishery.... The truth is this: Sharks will continue to be caught and killed on a wide scale by the more organized and sophisticated fishing nations. Targeting shark's fin soup will not stop this accidental catch. The fins from these catches will be thrown away or turned into animal feed and fertilizers if shark's fin soup is shunned."`

The Australian naturalist Steve Irwin was known to walk out of Chinese restaurants if he saw shark fin soup on the menu. American chef Ken Hom sees the West doing little to protect stocks of cod and caviar-producing sturgeon despite the outcry over shark-finning, but he also stresses the wastefulness of harvesting only the fins.

In 2006, Canadian filmmaker and photographer Rob Stewart created a film, Sharkwater, which exposes the shark fin industry in detail. In March 2011, the VOA Special English service of the Voice of America broadcast a 15-minute science program on shark finning.

In 2011, British celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay and his film crew visited Costa Rica to investigate illegal shark fin trading. After investigating the shark fins, Ramsay was held at gunpoint and doused in gasoline by gangsters for confronting them.

According to WildAid, opposition to shark finning in China has increased as a result of campaigns. In a 2008 survey in Beijing, 89% of respondents supported a ban on shark fin. A 2010 poll on Sina Weibo again indicated strong support for a ban on shark fin sales, with 27,370 respondents in favour and only 440 against. In an August 2013 survey of respondents from four cities in China, 91% supported a government ban on the shark fin trade.

Reporting

According to Giam Choo Hoo – the longest serving member of The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Animals Committee, and a representative of the shark fin industry in Singapore – "The perception that it is common practice to kill sharks for only their fins – and to cut them off whilst the sharks are still alive – is wrong.... The vast majority of fins in the market are taken from sharks after their death."

Researchers dispute this claim by pointing to the data: using a statistical analysis of shark fin industry trade data, a 2006 study estimated that between 26 and 73 million sharks are harvested each year worldwide. That figure, when converted to shark biomass, was three to four times higher than the catch recorded in Food and Agriculture Organization capture production statistics, the only global database of shark catches. According to the researchers, this discrepancy "may be attributable to factors... such as unrecorded shark landings, shark biomass recorded in [non-specific] categories, and/or a high frequency of shark finning and carcass disposal at sea." The marine conservationist, Meliane, says "Moreover, landing sharks and rays with fins attached will facilitate species identification, promote standardized data collection and reporting of official catch statistics, and eliminate potential enforcement loopholes." Because remains are not always correctly identified, reports and statistics from scientists are not always reliable. Simply put, they say that the industry is either under-reporting the sharks taken annually, or is frequently engaging in the practice of finning.

According to Shark Stewards, a non profit, environmentalist project, "Most shark fins go to Hong Kong for processing, and re-exported to China and other countries like the US. Fins traded as a dried product do not have any documentation of where that shark was captured, the species or if it was legally harvested or finned on the high seas." As a result, many consumers do not know where the fin came from, or if it was caught legally or illegally.

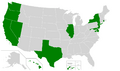

International restrictions

In 2013, 27 countries and the European Union had banned shark finning; international waters are unregulated. International fishing authorities are considering banning shark fishing (and finning) in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Finning is banned in the Eastern Pacific, but shark fishing and finning continues unabated in most of the Pacific and Indian Ocean. In countries such as Thailand and Singapore, public awareness advertisements on finning have reportedly reduced consumption by 25%.

There are four main categories of restrictions, as follows:

- A shark sanctuary is an area where shark fishing is entirely prohibited, this includes commercial fishing of all sharks, by-catching, the possession, trade, and sale of sharks & shark products. Although these acts against sharks are prohibited within these boundaries, nothing is really keeping the sharks within those boundaries, they can easily, unknowingly swim outside of the protected area and be fished, finned, or killed. As of March 2018, there are 17 shark sanctuaries in the world according to the article, "Shark Sanctuaries Around the World".

- Maldives - 353,742 sq. mi. (Established in 2010)

- Palau - 233,317 sq. mi. (Established in 2009)

- Federated States of Micronesia - 1,155,448 sq. mi. (Established in 2015)

- Marshall Islands - 769,205 sq. mi. (Established in 2015)

- Samoa - 49,421 sq. mi. (Established in 2018)

- New Caledonia - 480,697 sq. mi. (Established in 2013)

- Cook Islands - 756,812 sq. mi. (Established in 2012)

- French Polynesia - 1.840,642 sq. mi. (Established in 2012)

- Honduras - 92,757 sq. mi. (Established in 2011)

- The Bahamas - 242.971 sq. mi. (Established in 2011)

- Dominican Republic - 104,050 sq. mi. (Established in 2017)

- Cayman Islands - 45,998 sq. mi. (Established in 2015)

- Bonaire - 3,747 sq. mi. (Established in 2015)

- British Virgin Islands - 30,933 sq. mi. (Established in 2014)

- St. Maarten - 193 sq. mi. (Established in 2016)

- Saba - 3,102 sq. mi. (Established in 2015)

- Areas where sharks must be landed with fins attached;

- Areas where fin to body mass ratio-based regulations have been implemented;

- Areas where shark product trade regulations exist.

See also

In Spanish: Cercenamiento de las aletas de tiburón para niños

In Spanish: Cercenamiento de las aletas de tiburón para niños

- Chinese imperial cuisine

- Declawing of crabs

- Endangered sharks: many sharks are endangered as a consequence of the market for shark fins

- Pain in fish

- Shark culling

- Shark fin trading in Costa Rica

- Threatened sharks

Images for kids