Hammerhead shark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hammerhead sharkTemporal range: Middle Miocene to Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

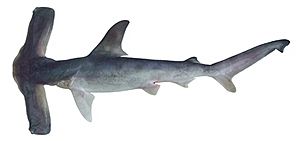

| A Hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

Sphyrnidae

|

| Genera | |

|

|

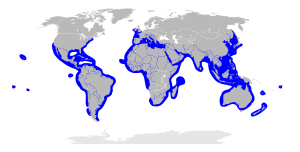

| Map of Hammerhead Sharks (In blue) | |

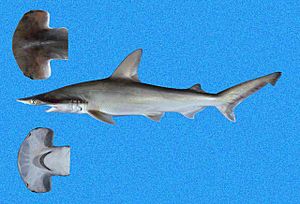

The Hammerhead sharks are a group of sharks named for the unusual and distinctive form of their heads. The "hammer" on its head is also known as the "cephalofoil". It allows them to see everything around them, including what is under them, and what is above them. It also gives the shark superior depth perception.

Hammerhead sharks make up the family Sphyrnidae.

Hammerheads are found worldwide, preferring life in warmer waters along coastlines and continental shelves, but during the summer, they participate in a mass migration to search for cooler waters.

Unlike most sharks, some hammerhead species will congregate and swim in large schools during the day, becoming solitary hunters at night.

Contents

Description

There are nine known species of Hammerhead sharks. They range from the length of 0.9 meters to the length of 6.1 meters, and weigh from 500 pounds (225 kg) to 1000 pounds (450 kg). They are usually light grey with a tint of green, but some are more greener in colour then others, and the belly in white.

The hammer-like head helps hammerhead sharks make very tight turns in the water, and it also helps them sense prey.

Hammerheads have disproportionately small mouths compared to other shark species.

Feeding

Hammerhead sharks are aggressive hunters and feed on crustaceans, molluscs like octopuses and squids, and many types of fish. They also eat other types of sharks. Hammerhead Sharks favourite type of food is stingrays.

They are known to swim along the bottom of the ocean, following their prey. Hammerhead sharks use their cephalofoil as a weapon to hunt for stingrays; they hit stingrays with their cephalofoil to weaken the stingray, and then eat the stingray.

When Hammerhead Sharks can not find food, they have been known to eat each other, but Great hammerhead sharks have been known to eat their own young.

Predators

Hammerhead sharks don't have natural predators. However, young hammerheads can become prey of other shark species, hungry killer whales or adult hammerheads.

Reproduction

Hammerhead Sharks are viviparous, meaning they give live birth. Females usually give birth to 12 to 15 pups at a time, but the Great hammerhead shark gives birth to around 20 to 40 pups at a time.

Once they are born, baby Hammerhead sharks come together in groups and swim towards warmer waters. They stay together in groups until they are older and big enough to live on their own. Hammerhead shark live for around 20 to 30 years.

In 2007, the bonnethead was found to be capable of asexual reproduction, making it the first shark to be able to do this.

Evolution

Since sharks do not have mineralized bones and rarely fossilize, only their teeth are commonly found as fossils. Their closest relatives are the requiem sharks (Carcharinidae). Based on DNA studies and fossils, the ancestor of the hammerheads probably lived in the Early Miocene epoch about 20 million years ago.

Sequence analysis shows they evolved from the Winghead shark.

Species

There are nine distinct species of Hammerhead shark in the wild:

| Species | Common names | IUCN Red List status | Population trend | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eusphyra blochii | Winghead shark | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna corona | Scalloped bonnethead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna gilberti | Carolina hammerhead | Unknown | ||

|

Sphyrna lewini | Scalloped hammerhead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna media | Scoophead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna mokarran | Great hammerhead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna tiburo | Bonnethead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna tudes | Smalleye hammerhead | Decreasing | ||

|

Sphyrna zygaena | Smooth hammerhead | Decreasing |

Relationship with humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, humans have been subjects of 17 documented, unprovoked attacks by hammerhead sharks within the genus Sphyrna since AD 1580. No human fatalities have been recorded. Most hammerhead shark species are too small to inflict serious damage to humans.

The great and the scalloped hammerheads are listed on the World Conservation Union's (IUCN) 2008 Red List as endangered, whereas the smalleye hammerhead is listed as vulnerable. The status given to these sharks is as a result of overfishing and demand for their fins, an expensive delicacy. Among others, scientists expressed their concern about the plight of the scalloped hammerhead at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Boston. The young swim mostly in shallow waters along shores all over the world to avoid predators.

Shark fins are prized as a delicacy in certain countries in Asia (such as China), and overfishing is putting many hammerhead sharks at risk of extinction. Fishermen who harvest the animals typically cut off the fins and toss the remainder of the fish, which is often still alive, back into the sea. This practice, known as finning, is lethal to the shark.

In captivity

The relatively small bonnethead is regular at public aquariums, as it has proven easier to keep in captivity than the larger hammerhead species, and it has been bred at a handful of facilities. Nevertheless, at up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in length and with highly specialized requirements, very few private aquarists have the experience and resources necessary to maintain a bonnethead in captivity. The larger hammerhead species can reach more than twice that size and are considered difficult, even compared to most other similar-sized sharks (such as Carcharhinus species, lemon shark, and sand tiger shark) regularly kept by public aquariums. They are particularly vulnerable during transport between facilities, may rub on surfaces in tanks, and may collide with rocks, causing injuries to their heads, so they require very large, specially adapted tanks. As a consequence, relatively few public aquaria have kept them for long periods. The scalloped hammerhead is the most frequently maintained large species, and it has been kept long term at public aquaria in most continents, but primarily in North America, Europe, and Asia. In 2014, fewer than 15 public aquaria in the world kept scalloped hammerheads. Great hammerheads have been kept at a few facilities in North America, including Atlantis Paradise Island Resort (Bahamas), Adventure Aquarium (New Jersey), Georgia Aquarium (Atlanta), Mote Marine Laboratory (Florida), and the Shark Reef at Mandalay Bay (Las Vegas). Smooth hammerheads have also been kept in the past.

Protection

Humans are the number one threat to hammerhead sharks. Although they are not usually the primary target, hammerhead sharks are caught in fisheries all over the world. Tropical fisheries are the most common place for hammerheads to be caught because of their preference to reside in warm waters. The total number of hammerheads caught in fisheries is recorded in the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Global Capture Production dataset. The number steadily increased from 75 metric tons in 1990, to 6,313 metric tons by 2010.

Shark fin traders say that hammerheads have some of the best quality fin needles which makes them good to eat when prepared properly. Hong Kong is the world's largest fin trade market and accounts for about 1.5% of the total annual amount of fins traded. It is estimated that around 375,000 great hammerhead sharks alone are traded per year which is equivalent to 21,000 metric tons of biomass. However, it is important to note that most sharks that are caught are only used for their fins and then discarded. The actual meat of hammerheads is generally unwanted. Consumption of regular hammerhead meat has been recorded in countries such as Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela, Kenya, and Japan.

In March 2013, three endangered, commercially valuable sharks, the hammerheads, the oceanic whitetip, and porbeagle, were added to Appendix II of CITES, bringing shark fishing and commerce of these species under licensing and regulation.

Cultural significance

Among Torres Strait Islanders, the hammerhead shark, known as the beizam, is a common family totem and often represented in cultural artefacts such as the elaborate headdresses worn for ceremonial dances, known as dhari (dari). They are associated with law and order. Renowned artist Ken Thaiday Snr is known for his representations of beizam in his sculptural dari and other works.

In native Hawaiian culture, sharks are considered to be gods of the sea, protectors of humans, and cleaners of excessive ocean life. Some of these sharks are believed to be family members who died and have been reincarnated into shark form, but others are considered man-eaters, also known as niuhi. These sharks include great white sharks, tiger sharks, and bull sharks. The hammerhead shark, also known as mano kihikihi, is not considered a man-eater or niuhi; it is considered to be one of the most respected sharks of the ocean, an aumakua. Many Hawaiian families believe that they have an aumakua watching over them and protecting them from the niuhi. The hammerhead shark is thought to be the birth animal of some children. Hawaiian children who are born with the hammerhead shark as an animal sign are believed to be warriors and are meant to sail the oceans. Hammerhead sharks rarely pass through the waters of Maui, but many Maui natives believe that their swimming by is a sign that the gods are watching over the families, and the oceans are clean and balanced.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tiburón martillo para niños

In Spanish: Tiburón martillo para niños