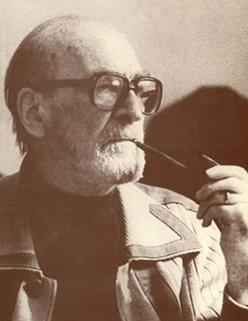

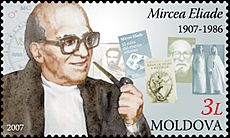

Mircea Eliade facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mircea Eliade

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | March 13, 1907 Bucharest, Kingdom of Romania |

| Died | April 22, 1986 (aged 79) Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Resting place | Oak Woods Cemetery |

| Occupation | Historian, philosopher, short story writer, journalist, essayist, novelist |

| Language | |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Citizenship | Romania United States |

| Education | |

| Period | 1921–1986 |

| Genre | Fantasy, autobiography, travel literature |

| Subject | History of religion, philosophy of religion, cultural history, political history |

| Literary movement | Modernism Criterion Trăirism |

| Parents | Gheorghe Eliade Jeana née Vasilescu |

Mircea Eliade (Romanian: [ˈmirtʃe̯a eliˈade]; March 13 [O.S. February 28] 1907 – April 22, 1986) was a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago.

Biography

Born in Bucharest, he was the son of Romanian Land Forces officer Gheorghe Eliade (whose original surname was Ieremia) and Jeana née Vasilescu. An Orthodox believer, Gheorghe Eliade registered his son's birth four days before the actual date, to coincide with the liturgical calendar feast of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. Mircea Eliade had a sister, Corina, the mother of semiologist Sorin Alexandrescu. His family moved between Tecuci and Bucharest, ultimately settling in the capital in 1914, and purchasing a house on Melodiei Street, near Piața Rosetti, where Mircea Eliade resided until late in his teens.

Eliade kept a particularly fond memory of his childhood and, later in life, wrote about the impact various unusual episodes and encounters had on his mind. In one instance during the World War I Romanian Campaign, when Eliade was about ten years of age, he witnessed the bombing of Bucharest by German zeppelins and the patriotic fervor in the occupied capital at news that Romania was able to stop the Central Powers' advance into Moldavia.

He described this stage in his life as marked by an unrepeatable epiphany.

Robert Ellwood, a professor of religion who did his graduate studies under Mircea Eliade, saw this type of nostalgia as one of the most characteristic themes in Eliade's life and academic writings.

After completing his primary education at the school on Mântuleasa Street, Eliade attended the Spiru Haret National College in the same class as Arșavir Acterian, Haig Acterian, and Petre Viforeanu (and several years the senior of Nicolae Steinhardt, who eventually became a close friend of Eliade's). Among his other colleagues was future philosopher Constantin Noica and Noica's friend, future art historian Barbu Brezianu.

As a child, Eliade was fascinated with the natural world, which formed the setting of his very first literary attempts, as well as with Romanian folklore and the Christian faith as expressed by peasants. Growing up, he aimed to find and record what he believed was the common source of all religious traditions. The young Eliade's interest in physical exercise and adventure led him to pursue mountaineering and sailing, and he also joined the Romanian Boy Scouts.

With a group of friends, he designed and sailed a boat on the Danube, from Tulcea to the Black Sea. In parallel, Eliade grew estranged from the educational environment, becoming disenchanted with the discipline required and obsessed with the idea that he was uglier and less virile than his colleagues. In order to cultivate his willpower, he would force himself to swallow insects and only slept four to five hours a night. At one point, Eliade was failing four subjects, among which was the study of the Romanian language.

Instead, he became interested in natural science and chemistry, as well as the occult, and wrote short pieces on entomological subjects. Despite his father's concern that he was in danger of losing his already weak eyesight, Eliade read passionately. One of his favorite authors was Honoré de Balzac, whose work he studied carefully. Eliade also became acquainted with the modernist short stories of Giovanni Papini and social anthropology studies by James George Frazer.

His interest in the two writers led him to learn Italian and English in private, and he also began studying Persian and Hebrew. At the time, Eliade became acquainted with Saadi's poems and the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh. He was also interested in philosophy—studying, among others, Socrates, Vasile Conta, and the Stoics Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus, and read works of history—the two Romanian historians who influenced him from early on were Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu and Nicolae Iorga. His first published work was the 1921 Inamicul viermelui de mătase ("The Silkworm's Enemy"), followed by Cum am găsit piatra filosofală ("How I Found the Philosophers' Stone"). Four years later, Eliade completed work on his debut volume, the autobiographical Novel of the Nearsighted Adolescent.

His literary works belong to the fantastic and autobiographical genres. The best known are the novels Maitreyi ('La Nuit Bengali' or 'Bengal Nights'), Noaptea de Sânziene ('The Forbidden Forest'), Isabel și apele diavolului ('Isabel and the Devil's Waters'), and Romanul Adolescentului Miop ('Novel of the Nearsighted Adolescent'); the novellas Domnișoara Christina ('Miss Christina') and Tinerețe fără tinerețe ('Youth Without Youth'); and the short stories Secretul doctorului Honigberger ('The Secret of Dr. Honigberger') and La Țigănci ('With the Gypsy Girls').

Early in his life, Eliade was a journalist and essayist, a disciple of Romanian philosopher and journalist Nae Ionescu, and a member of the literary society Criterion. In the 1940s, he served as cultural attaché to the United Kingdom and Portugal. Several times during the late 1930s, Eliade publicly expressed his support for the Iron Guard, a Christian fascist political organization. His political involvement at the time, as well as his other far right connections, were frequently criticised after World War II.

In 1966, Mircea Eliade became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He also worked as editor-in-chief of Macmillan Publishers' Encyclopedia of Religion, and, in 1968, lectured in religious history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. It was also during that period that Mircea Eliade completed his voluminous and influential History of Religious Ideas, which grouped together the overviews of his main original interpretations of religious history. He occasionally traveled out of the United States, attending the Congress for the History of Religions in Marburg (1960), and visiting Sweden and Norway in 1970.

During his later years, Eliade's writing career was hampered by severe arthritis. The last academic honors bestowed upon him were the French Academy's Bordin Prize (1977) and the title of Doctor Honoris Causa, granted by George Washington University (1985).

Mircea Eliade died at the Bernard Mitchell Hospital in April 1986. Eight days previously, he suffered a stroke while reading Emil Cioran's Exercises of Admiration, and had subsequently lost his speech function.

His body was cremated in Chicago, and the funeral ceremony was held on University grounds, at the Rockefeller Chapel. His grave is located in Oak Woods Cemetery.

Noted for his vast erudition, Eliade had fluent command of five languages (Romanian, French, German, Italian, and English) and a reading knowledge of three others (Hebrew, Persian, and Sanskrit). He was elected a posthumous member of the Romanian Academy.

Work

Eliade is known for his attempt to find broad, cross-cultural parallels and unities in religion, particularly in myths. Eliade notes that, in traditional societies, myth represents the absolute truth about primordial time. According to the myths, this was the time when the Sacred first appeared, establishing the world's structure—myths claim to describe the primordial events that made society and the natural world be that which they are. Eliade argues that all myths are, in that sense, origin myths: "myth, then, is always an account of a creation."

Many traditional societies believe that the power of a thing lies in its origin. If origin is equivalent to power, then "it is the first manifestation of a thing that is significant and valid" (a thing's reality and value therefore lies only in its first appearance).

Eliade argues that traditional man attributes no value to the linear march of historical events: only the events of the mythical age have value. To give his own life value, traditional man performs myths and rituals. Because the Sacred's essence lies only in the mythical age, only in the Sacred's first appearance, any later appearance is actually the first appearance; by recounting or re-enacting mythical events, myths and rituals "re-actualize" those events.

Eliade called this concept the "eternal return" (distinguished from the philosophical concept of "eternal return").

Eliade argues that yearning to remain in the mythical age causes a "terror of history": traditional man desires to escape the linear succession of events (which, Eliade indicated, he viewed as empty of any inherent value or sacrality). Eliade suggests that the abandonment of mythical thought and the full acceptance of linear, historical time, with its "terror", is one of the reasons for modern man's anxieties.

Eliade acknowledges that not all religious behavior has all the attributes described in his theory of sacred time and the eternal return. The Zoroastrian, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions embrace linear, historical time as sacred or capable of sanctification, while some Eastern traditions largely reject the notion of sacred time, seeking escape from the cycles of time.

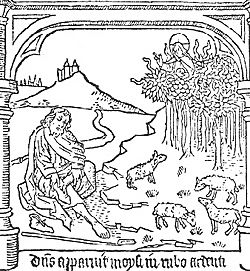

A recurrent theme in Eliade's myth analysis is the axis mundi, the Center of the World. According to Eliade, the Cosmic Center is a necessary corollary to the division of reality into the Sacred and the profane.

Because profane space gives man no orientation for his life, the Sacred must manifest itself in a hierophany, thereby establishing a sacred site around which man can orient himself. The site of a hierophany establishes a "fixed point, a center". This Center abolishes the "homogeneity and relativity of profane space", for it becomes "the central axis for all future orientation".

A manifestation of the Sacred in profane space is, by definition, an example of something breaking through from one plane of existence to another. Therefore, the initial hierophany that establishes the Center must be a point at which there is contact between different planes—this, Eliade argues, explains the frequent mythical imagery of a Cosmic Tree or Pillar joining Heaven, Earth, and the underworld.

Eliade's scholarly work also includes a study of shamanism.

Philosophy

In addition to his political essays, the young Mircea Eliade authored others, philosophical in content. One of Eliade's noted contributions was the 1932 Soliloquii ('Soliloquies'), which explored existential philosophy.

Cultural legacy

Tributes

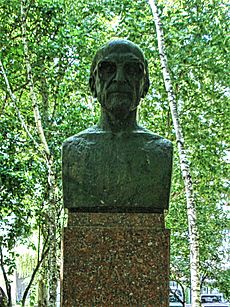

An endowed chair in the History of Religions at the University of Chicago Divinity School was named after Eliade in recognition of his wide contribution to the research on this subject; the current (and first incumbent) holder of this chair is Wendy Doniger.

To evaluate the legacy of Eliade and Joachim Wach within the discipline of the history of religions, the University of Chicago chose 2006 (the intermediate year between the 50th anniversary of Wach's death and the 100th anniversary of Eliade's birth), to hold a two-day conference in order to reflect upon their academic contributions and their political lives in their social and historical contexts, as well as the relationship between their works and their lives.

In 1990, after the Romanian Revolution, Eliade was elected posthumously to the Romanian Academy.

A Romanian Television 1 poll carried out in 2006 nominated Mircea Eliade as the 7th Greatest Romanian in history; his case was argued by the journalist Dragoş Bucurenci (see 100 greatest Romanians). His name was given to a boulevard in the northern Bucharest area of Primăverii, to a street in Cluj-Napoca, and to high schools in Bucharest, Sighişoara, and Reşiţa. The Eliades' house on Melodiei Street was torn down during the communist regime, and an apartment block was raised in its place; his second residence, on Dacia Boulevard, features a memorial plaque in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Mircea Eliade para niños

In Spanish: Mircea Eliade para niños

- Sântoaderi, supernatural entities found in Romanian folklore

Images for kids

-

Eliade's home in Bucharest (1934–1940)

-

The Cosmic Tree Yggdrasill, as depicted in a 17th-century Icelandic miniature