Nicolae Iorga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nicolae Iorga

|

|

|---|---|

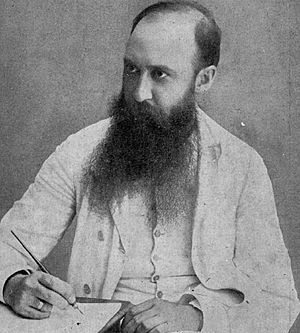

Nicolae Iorga in 1914 (photograph published in Luceafărul)

|

|

| 34th Prime Minister of Romania | |

| In office 19 April 1931 – 6 June 1932 |

|

| Monarch | Carol II |

| Preceded by | Gheorghe Mironescu |

| Succeeded by | Alexandru Vaida-Voievod |

| President of the Senate of Romania | |

| In office 9 June 1939 – 13 June 1939 |

|

| Monarch | Carol II |

| Preceded by | Alexandru Lapedatu |

| Succeeded by | Constantin Argetoianu |

| President of the Assembly of Deputies | |

| In office 9 December 1919 – 26 March 1920 |

|

| Monarch | Ferdinand I |

| Preceded by | Alexandru Vaida-Voevod |

| Succeeded by | Duiliu Zamfirescu |

| Member of the Crown Council | |

| In office 30 March 1938 – 6 September 1940 |

|

| Monarch | Carol II |

| Minister of Internal Affairs | |

| Acting 18 April 1931 – 7 May 1931 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Ion Mihalache |

| Succeeded by | Constantin Argetoianu (Acting) |

| Minister of Culture and Religious Affairs | |

| In office 18 April 1931 – 5 June 1932 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Nicolae Costăchescu |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrie Gusti |

| President of the Democratic Nationalist Party | |

| In office 6 May 1910 – 16 December 1938 Serving with A. C. Cuza (until 26 April 1920)

|

|

| Preceded by | None (co-founder) |

| Succeeded by | None (party formally banned under the 1938 Constitution) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 January 1871 Botoșani, Principality of Romania |

| Died | 27 November 1940 (aged 69) Strejnic, Prahova County, Kingdom of Romania |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Political party | Democratic Nationalist Party (1910–1938) National Renaissance Front (1938–1940) |

| Spouses |

Maria Tasu

(m. 1890; div. 1900)Ecaterina Bogdan

(m. 1901–1940) |

| Alma mater | Alexandru Ioan Cuza University École pratique des hautes études Leipzig University |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, professor, literary critic, politician |

| Profession | Historian, philosopher |

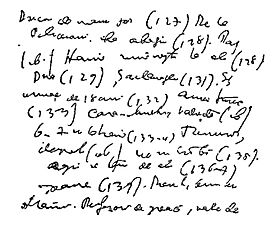

| Signature | |

Nicolae Iorga ( sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga; 17 January 1871 – 27 November 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, Albanologist, poet and playwright.

Contents

Biography

Born into a family of Greek origin, Nicolae Iorga was a native of Botoșani. His father, Nicu Iorga, was a practicing lawyer; he ultimately descended from a Greek merchant who settled in Botoșani in the 18th century, five generations before Nicolae Iorga's birth. His mother, Zulnia Iorga (née Arghiropol), was a woman of Phanariote Greek descent. Iorga claimed direct descent from the noble Mavrocordatos and Argyros families.

In 1876, aged thirty-seven or thirty-eight, Iorga's father was incapacitated by an unknown illness and died, leaving Nicolae and his younger brother George orphans—a loss which, the historian would recall in writing, dominated the image he had of his own childhood. In 1878, Iorga was enlisted at the Marchian Folescu School, where, as he took pride in noting, he excelled in most areas, discovering a love for intellectual pursuits and, by age nine, even being allowed by his teachers to lecture his schoolmates in Romanian history. His history teacher, a refugee Pole, sparked his interest in research and his lifelong Polonophilia. Iorga also credited this earliest formative period with having shaped his lifelong views on Romanian language and local culture: "I learned Romanian ... as it was spoken back in the day: plainly, beautifully and above all resolutely and colorfully, without the intrusions of newspapers and best-selling books". He credited the 19th century polymath Mihail Kogălniceanu, whose works he had first been reading as a child, with having shaped this literary preference.

A student at Botoșani's A. T. Laurian gymnasium and high school after 1881, the young Iorga received top honors, and, beginning 1883, began tutoring some of his colleagues to increase his family's main revenue (according to Iorga, a "miserable pension of pittance"). Aged thirteen, while on extended visit to his maternal uncle Emanuel "Manole" Arghiropol, he also made his press debut with paid contributions to Arghiropol's Romanul newspaper, including anecdotes and editorial pieces on European politics. The year 1886 was described by Iorga as "the catastrophe of my school life in Botoșani": on temporary suspension for not having greeted a teacher, Iorga opted to leave the city and apply for the National High School of Iași, being received into the scholarship program and praised by his new principal, the philologist Vasile Burlă. The adolescent was already fluent in French, Italian, Latin and Greek, later referring to Greek studies as "the most refined form of human reasoning".

By age seventeen, Iorga was becoming more rebellious. This was the time when he first grew interested in political activities, but displaying convictions which he later strongly disavowed: a self-confessed Marxist, Iorga promoted the left-wing magazine Viața Socială, and lectured on Das Kapital. Seeing himself confined in the National College's "ugly and disgusting" boarding school, he defied its rules and was suspended a second time, losing scholarship privileges. Before readmission, he decided not to fall back on his family's financial support, and instead returned to tutoring others. Again expelled for reading during a teacher's lesson, Iorga still graduated in the top "first prize" category (with a 9.24 average) and subsequently took his Baccalaureate with honors.

In 1888, Nicolae Iorga passed his entry examination for the University of Iași Faculty of Letters, becoming eligible for a scholarship soon after. Upon the completion of his second term, he also received a special dispensation from the Kingdom of Romania's Education Ministry, and, as a result, applied for and passed his third term examinations, effectively graduating one year ahead of his class. Before the end of the year, he also passed his license examination magna cum laude, with a thesis on Greek literature, an achievement which consecrated his reputation inside both academia and the public sphere. Hailed as a "morning star" by the local press and deemed a "wonder of a man" by his teacher A. D. Xenopol, Iorga was honored by the faculty with a special banquet. Three academics (Xenopol, Nicolae Culianu, Ioan Caragiani) formally brought Iorga to the attention of the Education Ministry, proposing him for the state-sponsored program which allowed academic achievers to study abroad.

Iorga made his first study trips to Italy (April and June 1890), and subsequently left for a longer stay in France, enlisting at the École pratique des hautes études. He was a contributor for the Encyclopédie française, personally recommended there by Slavist Louis Léger. Reflecting back on this time, he stated: "I never had as much time at my disposal, as much freedom of spirit, as much joy of learning from those great figures of mankind ... than back then, in that summer of 1890". While preparing for his second diploma, Iorga also pursued his interest in philology, learning English, German, and rudiments of other Germanic languages. In 1892, he was in England and in Italy, researching historical sources for his French-language thesis on Philippe de Mézières, a Frenchman in the Crusade of 1365. In tandem, he became a contributor to Revue Historique, a leading French academic journal.

Between 1890 and the end of 1893, he had published three works: his debut in poetry (Poezii, "Poems"), the first volume of Schițe din literatura română ("Sketches on Romanian Literature", 1893; second volume 1894), and his Leipzig thesis, printed in Paris as Thomas III, marquis de Saluces. Étude historique et littéraire ("Thomas, Margrave of Saluzzo. Historical and Literary Study").

Making his comeback to Romania in October 1894, Iorga settled in the capital city of Bucharest. He changed residence several times, until eventually settling in Grădina Icoanei area. He agreed to compete in a sort of debating society, with lectures which only saw print in 1944. He applied for the Medieval History Chair at the University of Bucharest, submitting a dissertation in front of an examination commission comprising historians and philosophers (Caragiani, Odobescu, Xenopol, alongside Aron Densușianu, Constantin Leonardescu and Petre Râșcanu), but totaled a 7 average which only entitled him to a substitute professor's position. The achievement, at age 23, was still remarkable in its context.

In 1904, he published the historical geography work Drumuri și orașe din România ("Roads and Towns of Romania") and, upon the special request of National Liberal Education Minister Spiru Haret, a work dedicated to the celebrated Moldavian Prince Stephen the Great, published upon the 400th anniversary of the monarch's death as Istoria lui Ștefan cel Mare ("The History of Stephen the Great").

In 1906, Iorga traveled into the Ottoman Empire, visiting Istanbul, and published another set of volumes—Contribuții la istoria literară ("Contributions to Literary History"), Neamul românesc în Ardeal și Țara Ungurească ("The Romanian Nation in Transylvania and the Hungarian Land"), Negoțul și meșteșugurile în trecutul românesc ("Trade and Crafts of the Romanian Past") etc. In 1907, he began issuing a second periodical, the cultural magazine Floarea Darurilor, and published with Editura Minerva an early installment of his companion to Romanian literature (second volume 1908, third volume 1909). His published scientific contributions for that year include, among others, an English-language study on the Byzantine Empire.

In 1908, he and his family decided to relocate, moving to a villa in Vălenii de Munte, a town nestled in the remote hilly area of Prahova County. Once settled, Iorga set up a specialized summer school, his own publishing house, a printing press and the literary supplement of Neamul Românesc, as well as an asylum managed by writer Constanța Marino-Moscu. He published some 25 new works for that year, such as the introductory volumes for his German-language companion to Ottoman history (Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches, "History of the Ottoman Empire"), a study on Romanian Orthodox institutions (Istoria bisericii românești, "The History of the Romanian Church"), and an anthology on Romanian Romanticism. He followed up in 1909 with a volume of parliamentary speeches, În era reformelor ("In the Age of Reforms"), a book on the 1859 Moldo–Wallachian Union (Unirea principatelor, "The Principalities' Union"), and a critical edition of poems by Eminescu.

Co-founder (in 1910) of the Democratic Nationalist Party (PND), he served as a member of Parliament, President of the Deputies' Assembly and Senate, cabinet minister and briefly (1931–32) as Prime Minister. A child prodigy, polymath and polyglot, Iorga produced an unusually large body of scholarly works, establishing his international reputation as a medievalist, Byzantinist, Latinist, Slavist, art historian and philosopher of history. Holding teaching positions at the University of Bucharest, the University of Paris and several other academic institutions, Iorga was founder of the International Congress of Byzantine Studies and the Institute of South-East European Studies (ISSEE). His activity also included the transformation of Vălenii de Munte town into a cultural and academic center.

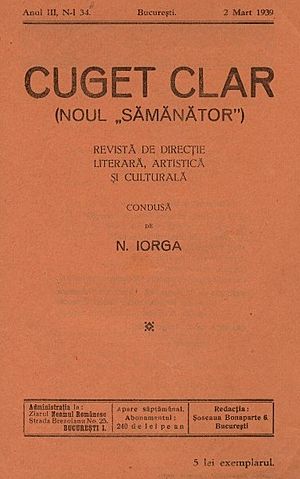

In parallel with his academic contributions, Nicolae Iorga was a prominent right-of-centre activist, whose political theory bridged conservatism, Romanian nationalism, and agrarianism. From Marxist beginnings, he switched sides and became a maverick disciple of the Junimea movement. Iorga later became a leadership figure at Sămănătorul, the influential literary magazine with populist leanings, and militated within the League for the Cultural Unity of All Romanians, founding vocally conservative publications such as Neamul Românesc, Drum Drept, Cuget Clar and Floarea Darurilor. His support for the cause of ethnic Romanians in Austria-Hungary made him a prominent figure in the pro-Entente camp by the time of World War I, and ensured him a special political role during the interwar existence of Greater Romania. Initiator of large-scale campaigns to defend Romanian culture in front of perceived threats, Iorga sparked most controversy with his antisemitic rhetoric, and was for long an associate of the far-right ideologue A. C. Cuza. He was an adversary of the dominant National Liberals, later involved with the opposition Romanian National Party.

Iorga became Romanian Premier in April 1931, upon the request of Carol II, who had returned from exile to replace his own son, Michael I. Once confirmed on the throne, Carol experimented with technocracy, borrowing professionals from various political groups, and closely linking Iorga with Internal Affairs Minister Constantin Argetoianu. During his short term, Iorga traveled throughout the country, visiting around 40 cities and towns, and was notably on a state visit to France, being received by Prime Minister Aristide Briand and by Briand's ally André Tardieu. In recognition of his merits as an Albanologist, the Albanian Kingdom granted Iorga property in Sarandë town, on which the scholar created a Romanian Archeological Institute.

The major issue facing Iorga was the economic crisis, part of the Great Depression, and he was largely unsuccessful in tackling it. To the detriment of financial markets, the cabinet tried to implement debt relief for bankrupt land cultivators, and signed an agreement with Argentina, another exporter of agricultural produce, to try to limit deflation. The mishandling of economic affairs made the historian a target of derision and indignation among the general public. The reduction of deficit with pay cuts for all state employees ("sacrificial curves") or selective layoffs was particularly dramatic, leading to widespread disillusionment among the middle class.

Nicolae Iorga presented his cabinet's resignation in May 1932, returning to academic life.

The backdrop to Iorga's mandate was Carol's conflict with the Iron Guard, an increasingly popular fascist organization. In March 1932, Iorga signed a decree outlawing the movement, the beginning of his clash with the Guard's founder Corneliu Zelea Codreanu.

The year 1940 saw the collapse of Carol II's regime. The unexpected cession of Bessarabia to the Soviets shocked Romanian society and greatly angered Iorga. At the two sessions of the Crown Council held on 27 June, he was one of six (out of 21) members to reject the Soviet ultimatum demanding Bessarabia's handover, instead calling vehemently for armed resistance. Later, the Nazi-mediated Second Vienna Award made Northern Transylvania a part of Hungary. This loss sparked a political and moral crisis, eventually leading to the establishment of a National Legionary State with Ion Antonescu as Conducător and the Iron Guard as a governing political force. He received renewed threats from the Iron Guard, including hate mail, attacks in the movement's press (Buna Vestire and Porunca Vremii) and tirades from the Guardist section in Vălenii.

Nicolae Iorga was forced out of Bucharest (where he owned a new home in Dorobanți quarter) and Vălenii de Munte by the massive earthquake of November. He then moved to Sinaia, where he gave the finishing touches to his book Istoriologia umană ("Human Historiology"). Iorga remained an independent voice of opposition after the Guard inaugurated its own National Legionary dictatorship, but was ultimately assassinated by a Guardist squad on the afternoon of 27 November in the vicinity of Strejnic (some distance from the city of Ploiești).

Iorga's death caused much consternation among the general public, and was received with particular concern by the academic community. Forty-seven universities worldwide flew their flags at half-staff. A funeral speech was delivered by the exiled French historian Henri Focillon, from New York City, calling Iorga "one of those legendary personalities planted, for eternity, in the soil of a country and the history of human intelligence." At home, the Iron Guard banned all public mourning, excepting an obituary in Universul daily and a ceremony hosted by the Romanian Academy. The final oration was delivered by philosopher Constantin Rădulescu-Motru, who noted, in terms akin to those used by Focillon, that the murdered scientist had stood for "our nation's intellectual prowess", "the full cleverness and originality of the Romanian genius".

Iorga's remains were buried at Bellu, in Bucharest, on the same day as Madgearu's funeral—the attendants, who included some of the surviving interwar politicians and foreign diplomats, defied the Guard's ban with their presence. Iorga's last texts, recovered by his young disciple G. Brătescu, were kept by literary critic Șerban Cioculescu and published at a later date. Gheorghe Brătianu later took over Iorga's position at the South-East Europe Institute and the Institute of World History (known as Nicolae Iorga Institute from 1941).

Scientific work

Iorga the European scholar has drawn comparisons with figures such as Voltaire, Jules Michelet, Leopold von Ranke and Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz. Having achieved fluency in some 12 foreign languages, he was an exceptionally prolific author: according to his biographer Barbu Theodorescu, the total of his published contributions, both volumes and brochures, was 1,359. His work in documenting Romania's historical past could reach an unprecedented intensity, one such exceptional moment being a 1903 study trip to Târgu Jiu, a three-day interval during which he copied and summarized 320 individual documents, covering the period 1501–1833. His mentor and rival Xenopol was among the first voices to discuss his genius, his 1911 Academy speech in honor of Nicolae Iorga making special note of his "absolutely extraordinary memory" and his creative energy, and concluding: "one asks himself in wonder how a brain was able to conceive of so many things and a hand was able to record them". In 1940, Rădulescu-Motru likewise argued that Iorga had been "a creator ... of unparalleled fecundity", while Enciclopedia Cugetarea deemed him the greatest-ever mind in Romania. According to literary historian George Călinescu, Iorga's "huge" and "monstrously" comprehensive research, leaving no other historian "the joy of adding something", was matched by the everyday persona, a "hero of the ages".

The level of Iorga's productivity and the quality of his historical writing were also highlighted by more modern researchers. Literary historian Ovid Crohmălniceanu opined that Iorga's scientific work was one of the "illustrious accomplishments" of the interwar years, on par with Constantin Brâncuși's sculptures and George Enescu's music. Romanian historian of culture Alexandru Zub finds that Iorga's is "surely the richest opus coming from the 20th century", while Maria Todorova calls Iorga "Romania's greatest historian", adding "at least in terms of the size of his opus and his influence both at home and abroad". According to philosopher Liviu Bordaș, Iorga's main topic of interest, the relation between Romania and the Eastern world, was exhaustively covered: "nothing escaped this sacred monster's attention: Iorga had read everything."

Legacy

Scholarly impact, portrayals and landmarks

The fields of scientific inquiry opened by Iorga, in particular his study into the origin of the Romanians, were taken up after his death by other researchers: Gheorghe Brătianu, Constantin C. Giurescu, P. P. Panaitescu, Șerban Papacostea, Henri H. Stahl. As cultural historian, Iorga found a follower in N. Cartojan, while his thoughts on the characteristics of Romanianness inspired the social psychology of Dimitrie Drăghicescu. In the postmodern age, Iorga's pronouncements on the subject arguably contributed to the birth of Romanian imagological, post-colonial and cross-cultural studies. The idea of Romanii populare has endured as a popular working hypothesis in Romanian archeology.

Aside from being himself a writer, Iorga's public image was also preserved in the literary work of both his colleagues and adversaries. One early example is a biting epigram by Ion Luca Caragiale, where Iorga is described as the dazed savant. In addition to the many autobiographies which discuss him, he is a hero in various works of fiction. As geographer Cristophor Arghir, he is the subject of a thinly disguised portrayal in the Bildungsroman În preajma revoluței ("Around the Time of the Revolution"), written by his rival Constantin Stere in the 1930s. Celebrated Romanian satirist and Viața Românească affiliate Păstorel Teodoreanu was engaged in a lengthy polemic with Iorga, enshrining Iorga in Romanian humor as a person with little literary skill and an oversized ego, and making him the subject of an entire collection of poems and articles, Strofe cu pelin de mai pentru Iorga Neculai ("Stanzas in May Wormwood for Iorga Neculai"). One of Teodoreanu's own epigrams in Contimporanul ridiculed Moartea lui Dante, showing the resurrected Dante Alighieri pleading with Iorga to be left in peace. Iorga was also identified as the subject of fictional portrayals in a modernist novel by N. D. Cocea and (against the author's disclaimer) in George Ciprian's play The Drake's Head.

Iorga became the subject of numerous visual portrayals. Some of the earliest were satires, such as an 1899 portrait of him as a Don Quixote (the work of Nicolae Petrescu Găină) and images of him as a ridiculously oversized character, in Ary Murnu's drawings for Furnica review. Later, Iorga's appearance inspired the works of some other visual artists, including his own daughter Magdalina (Magda) Iorga, painter Constantin Piliuță and sculptor Ion Irimescu, who was personally acquainted with the scholar. Irimescu's busts of Iorga are located in places of cultural importance: the ISSEE building in Bucharest and a public square in Chișinău, Moldova (ex-Soviet Bessarabia). The city has another Iorga bust, the work of Mihail Ecobici, in the Aleea Clasicilor complex. Since 1994, Iorga's face is featured on a highly circulated Romanian leu bill: the 10,000 lei banknote, which became the 1 leu bill following a 2005 monetary reform.

Several Romanian cities have "Nicolae Iorga" streets or boulevards: Bucharest (also home of the Iorga High School and the Iorga Park), Botoșani, Brașov, Cluj-Napoca, Constanța, Craiova, Iași, Oradea, Ploiești, Sibiu, Timișoara, etc. In Moldova, his name was also assigned to similar locations in Chișinău and Bălți. The Botoșani family home, restored and partly rebuilt in 1965, is currently preserved as a Memorial House. The house in Vălenii is a memorial museum.

Political symbol

Iorga has enjoyed posthumous popularity in the decades since the Romanian Revolution of 1989: present at the top of "most important Romanians" polls in the 1990s, he was voted in at No. 17 in the 100 greatest Romanians televised poll. As early as 1989, the Iorga Institute was reestablished under Papacostea's direction. Since 1990, the Vălenii summer school has functioned regularly, having Iorga exegete Valeriu Râpeanu as a regular guest. In later years, the critical interpretation of Iorga's work, first proposed by Lucian Boia around 1995, was continued by a new school of historians, who distinguished between the nationalist-didactic and informative contents.

Descendants

Nicolae Iorga had over ten children from his marriages, but many of them died in infancy. In addition to Florica Chirescu, his children from Maria Tasu were Petru, Elena, Maria; with Catinca, he fathered Mircea, Ștefan, Magdalina, Liliana, Adriana, Valentin, and Alina. Magdalina, who enjoyed success as a painter, later started a family in Italy. The only one of his children to train in history, known for her work in reediting her father's books and her contribution as a sculptor, Liliana Iorga married fellow historian Dionisie Pippidi in 1943. Alina became the wife of an Argentine jurist, Francisco P. Laplaza.

Mircea Iorga was married into the aristocratic Știrbey family, and then to Mihaela Bohățiel, a Transylvanian noblewoman who was reputedly a descendant of the Lemeni clan and of the medieval magnate Johannes Benkner. He was for a while attracted to PND politics and also wrote poetry. An engineer by trade, he was headmaster of the Bucharest Electrotechnical College in the late 1930s. Another son, Ștefan N. Iorga, was a writer active with the Cuget Clar movement, and later a noted physician.

Iorga's niece Micaella Filitti, who worked as a civil servant in the 1930s, defected from Communist Romania and settled in France. Later descendants include historian Andrei Pippidi, son of Dionisie, who is noted as a main editor of Iorga's writings. Pippidi also prefaced collections of Iorga's correspondence, and published a biographical synthesis on his grandfather. Andrei Pippidi is married to political scientist and journalist Alina Mungiu, the sister of award-winning filmmaker Cristian Mungiu.

Images for kids

-

Memorial house in Botoșani

-

Iorga at the University of Paris, receiving his Honoris Causa Doctorate

See also

In Spanish: Nicolae Iorga para niños

In Spanish: Nicolae Iorga para niños