James Prescott Joule facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Prescott Joule

FRS FRSE

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1818 |

| Died | 11 October 1889 (aged 70) |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | Disproving caloric theory First law of thermodynamics Mechanical equivalent of heat Magnetostriction Joule cycle Joule effect Joule expansion Joule's first law Joule's second law Joule–Thomson effect |

| Spouse(s) |

Amelia Grimes

(m. 1847; died 1854) |

| Children | Benjamin Arthur Alice Amelia Henry |

| Awards | Royal Medal (1852) Copley Medal (1870) Albert Medal (1880) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Influences | John Dalton John Davies |

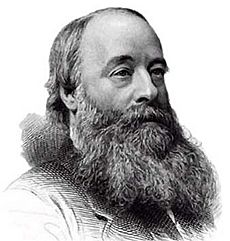

James Prescott Joule FRS FRSE (/dʒuːl/; 24 December 1818 – 11 October 1889) was an English physicist, mathematician and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work. This led to the law of conservation of energy, which in turn led to the development of the first law of thermodynamics. The SI derived unit of energy, the joule, is named after him.

He worked with Lord Kelvin to develop an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale, which came to be called the Kelvin scale. Joule also made observations of magnetostriction, and he found the relationship between the current through a resistor and the heat dissipated, which is also called Joule's first law. His experiments about energy transformations were first published in 1843.

Contents

Early years

James Joule was born in 1818, the son of Benjamin Joule (1784–1858), a wealthy brewer, and his wife, Alice Prescott, on New Bailey Street in Salford. Joule was tutored as a young man by the famous scientist John Dalton and was strongly influenced by chemist William Henry and Manchester engineers Peter Ewart and Eaton Hodgkinson. He was fascinated by electricity, and he and his brother experimented by giving electric shocks to each other and to the family's servants.

As an adult, Joule managed the brewery. Science was merely a serious hobby. Sometime around 1840, he started to investigate the feasibility of replacing the brewery's steam engines with the newly invented electric motor. His first scientific papers on the subject were contributed to William Sturgeon's Annals of Electricity. Joule was a member of the London Electrical Society, established by Sturgeon and others.

Motivated in part by a businessman's desire to quantify the economics of the choice, and in part by his scientific inquisitiveness, he set out to determine which prime mover was more efficient. He discovered Joule's first law in 1841, that the heat which is evolved by the proper action of any voltaic current is proportional to the square of the intensity of that current, multiplied by the resistance to conduction which it experiences. He went on to realize that burning a pound of coal in a steam engine was more economical than a costly pound of zinc consumed in an electric battery. Joule captured the output of the alternative methods in terms of a common standard, the ability to raise a mass weighing one pound to a height of one foot, the foot-pound.

However, Joule's interest diverted from the narrow financial question to that of how much work could be extracted from a given source, leading him to speculate about the convertibility of energy. In 1843 he published results of experiments showing that the heating effect he had quantified in 1841 was due to generation of heat in the conductor and not its transfer from another part of the equipment. This was a direct challenge to the caloric theory which held that heat could neither be created or destroyed. Caloric theory had dominated thinking in the science of heat since introduced by Antoine Lavoisier in 1783. Lavoisier's prestige and the practical success of Sadi Carnot's caloric theory of the heat engine since 1824 ensured that the young Joule, working outside either academia or the engineering profession, had a difficult road ahead. Supporters of the caloric theory readily pointed to the symmetry of the Peltier–Seebeck effect to claim that heat and current were convertible in an, at least approximately, reversible process.

The mechanical equivalent of heat

Further experiments and measurements with his electric motor led Joule to estimate the mechanical equivalent of heat as 4.1868 joules per calorie of work to raise the temperature of one gram of water by one Kelvin. He announced his results at a meeting of the chemical section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Cork in August 1843 and was met by silence.

Joule was undaunted and started to seek a purely mechanical demonstration of the conversion of work into heat. By forcing water through a perforated cylinder, he could measure the slight viscous heating of the fluid. He obtained a mechanical equivalent of 770 foot-pounds force per British thermal unit (4,140 J/Cal). The fact that the values obtained both by electrical and purely mechanical means were in agreement to at least one order of magnitude was, to Joule, compelling evidence of the reality of the convertibility of work into heat.

Joule now tried a third route. He measured the heat generated against the work done in compressing a gas. He obtained a mechanical equivalent of 798 foot-pounds force per British thermal unit (4,290 J/Cal). In many ways, this experiment offered the easiest target for Joule's critics but Joule disposed of the anticipated objections by clever experimentation. Joule read his paper to the Royal Society on 20 June 1844, but his paper was rejected for publication by the Royal Society and he had to be content with publishing in the Philosophical Magazine in 1845.

Joule here adopts the language of vis viva (energy), possibly because Hodgkinson had read a review of Ewart's On the measure of moving force to the Literary and Philosophical Society in April 1844.

In June 1845, Joule read his paper On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat to the British Association meeting in Cambridge. In this work, he reported his best-known experiment, involving the use of a falling weight, in which gravity does the mechanical work, to spin a paddle wheel in an insulated barrel of water which increased the temperature. He now estimated a mechanical equivalent of 819 foot-pounds force per British thermal unit (4,404 J/Cal). He wrote a letter to the Philosophical Magazine, published in September 1845 describing his experiment.

In 1850, Joule published a refined measurement of 772.692 foot-pounds force per British thermal unit (4,150 J/Cal), closer to twentieth century estimates.

Kinetic theory

Kinetics is the science of motion. Joule was a pupil of Dalton and it is no surprise that he had learned a firm belief in the atomic theory, even though there were many scientists of his time who were still skeptical. He had also been one of the few people receptive to the neglected work of John Herapath on the kinetic theory of gases. He was further profoundly influenced by Peter Ewart's 1813 paper On the measure of moving force.

Joule perceived the relationship between his discoveries and the kinetic theory of heat. His laboratory notebooks reveal that he believed heat to be a form of rotational, rather than translational motion.

Joule could not resist finding antecedents of his views in Francis Bacon, Sir Isaac Newton, John Locke, Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford) and Sir Humphry Davy. Though such views are justified, Joule went on to estimate a value for the mechanical equivalent of heat of 1,034 foot-pound from Rumford's publications. Some modern writers have criticised this approach on the grounds that Rumford's experiments in no way represented systematic quantitative measurements. In one of his personal notes, Joule contends that Mayer's measurement was no more accurate than Rumford's, perhaps in the hope that Mayer had not anticipated his own work.

Joule has been attributed with explaining the sunset green flash phenomenon in a letter to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1869; actually, he merely noted (with a sketch) the last glimpse as bluish green, without attempting to explain the cause of the phenomenon.

Published work

- Joule, J.P. (1841). "On the Heat evolved by Metallic Conductors of Electricity, and in the Cells of a Battery during Electrolysis". Philosophical Magazine 19 (124): 260. doi:10.1080/14786444108650416. https://books.google.com/books?id=hJEOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA260.

- Joule, J.P. (1843). "On the Calorific Effects of Magneto-Electricity, and on the Mechanical Value of Heat". Philosophical Magazine. 3 23 (154): 435–443. doi:10.1080/14786444308644766. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/20095#page/279/mode/1up.

- Joule, J.P. (1844). "On the Changes of Temperature Produced by the Rarefaction and Condensation of Air". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 5: 517–518. doi:10.1098/rspl.1843.0031. https://books.google.com/books?id=MfYrAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA517.

- Joule, J.P. (1845). "On the Changes of Temperature Produced by the Rarefaction and Condensation of Air". Philosophical Magazine. 3 26 (174): 369–383. doi:10.1080/14786444508645153. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/20067#page/382/mode/2up.

- Joule, J.P. (1845b). "On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat". Notices and Abstracts of Communications to the British Association for the Advancement of Science 15. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/46638#page/429/mode/1up. "read before the British Association at Cambridge, June 1845".

- Joule, J.P. (1845c). "On the Existence of an Equivalent Relation between Heat and the ordinary Forms of Mechanical Power". Philosophical Magazine. 3 27 (179): 205–207. doi:10.1080/14786444508645256. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/19987#page/219/mode/1up.

- Joule, J.P. (1850). "On the Mechanical Equivalent of Heat". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 140: 61–82. doi:10.1098/rstl.1850.0004. https://archive.org/stream/philtrans00608634/00608634#page/n0/mode/2up.

- Joule, J. P. (1884). The Scientific Papers of James Prescott Joule. London: Physical Society. OL239730M. https://archive.org/stream/scientificpapers01joul#page/n3/mode/2up.

- (in en) Joint scientific papers. London: Taylor and Francis. 1887. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=11939368.

Honours

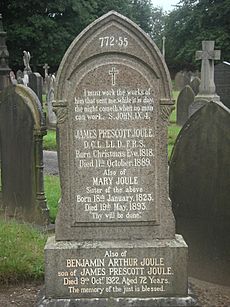

Joule died at home in Sale and is buried in Brooklands cemetery there. His gravestone is inscribed with the number "772.55", his climacteric 1878 measurement of the mechanical equivalent of heat, in which he found that this amount of foot-pounds of work must be expended at sea level to raise the temperature of one pound of water from 60 °F to 61 °F. There is also a quotation from the Gospel of John: "I must work the work of him that sent me, while it is day: the night cometh, when no man can work".[John 9:4] The Wetherspoon's pub in Sale, the town of his death, is named "The J. P. Joule" after him.

Joule's many honours and commendations include:

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1850)

- Royal Medal (1852), 'For his paper on the mechanical equivalent of heat, printed in the Philosophical Transactions for 1850'

- Copley Medal (1870), 'For his experimental researches on the dynamical theory of heat'

- President of Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society (1860)

- President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1872, 1887)

- Honorary Membership of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland (1857)

- Honorary degrees:

- LL.D., Trinity College, Dublin (1857)

- DCL, University of Oxford (1860)

- LL.D., University of Edinburgh (1871)

- Joule received a civil list pension of £200 per annum in 1878 for services to science

- Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts (1880), 'for having established, after most laborious research, the true relation between heat, electricity and mechanical work, thus affording to the engineer a sure guide in the application of science to industrial pursuits'

There is a memorial to Joule in the north choir aisle of Westminster Abbey, though he is not buried there, contrary to what some biographies state. A statue of Joule by Alfred Gilbert stands in Manchester Town Hall, opposite that of Dalton.

Family

In 1847, Joule married Amelia Grimes. Joule became a widower when she died in 1854, 7 years after their wedding. They had three children together: a son, Benjamin Arthur Joule (1850–1922), a daughter, Alice Amelia (1852–1899) and a second son, Joe (born 1854, who died three weeks later) Alice had grown to be a beautiful girl like her mother. Benjamin became strong like his father. Joule was proud of Alice and Benjamin. When James had died in 1889-Alice and Benjamin were devastated. 10 years later Alice had died Benjamin had been alone until he found a perfect wife which he married and died 1922.

See also

In Spanish: James Prescott Joule para niños

In Spanish: James Prescott Joule para niños

- Latent heat

- Sensible heat

- Internal energy