John Locke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Locke

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of John Locke by John Greenhill (died 1676)

|

|

| Born |

John Locke

29 August 1632 Wrington, Somerset, England

|

| Died | 28 October 1704 (aged 72) High Laver, Essex, England

|

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Christ Church, Oxford (BA, 1656; MA, 1658; MB, 1675) |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | University of Oxford Royal Society |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of mind, philosophy of education, economics |

|

Notable ideas

|

List

Consciousness

Consent of the governed Inverted spectrum Labor theory of property Law of opinion Lockean proviso Molyneux's problem Argument from ignorance Natural rights (rights of life, liberty and property) Primary/secondary quality distinction Semeiotike (the doctrine of signs) Social contract Sortal State of nature Tabula rasa |

| Signature | |

|

|

John Locke FRS ( 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". His work greatly affected the development of political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American Revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.

Locke's theory of mind is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self.

He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate, or tabula rasa. He maintained that we are born without innate ideas, and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perception, a concept now known as empiricism.

Early life

Locke was born on 29 August 1632, in a small thatched cottage by the church in Wrington, Somerset, about 12 miles from Bristol. He was baptised the same day, as both of his parents were Puritans. Locke's father, also named John, was an attorney who served as clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna and as a captain of cavalry for the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War. His mother was Agnes Keene. Soon after Locke's birth, the family moved to the market town of Pensford, about seven miles south of Bristol, where Locke grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London under the sponsorship of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and John Sr.'s former commander. At the age of 16 he was at school just half a mile away from the execution of Charles I; however, the boys were not allowed to go and watch. After completing studies at Westminster, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford, in the autumn of 1652 at the age of 20. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster School, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member.

Locke was awarded a bachelor's degree in February 1656 and a master's degree in June 1658. He obtained a bachelor of medicine in February 1675, having studied the subject extensively during his time at Oxford and, in addition to Lower, worked with such noted scientists and thinkers as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis and Robert Hooke. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Ashley was impressed with Locke and persuaded him to become part of his retinue.

Career

Work

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Ashley's home at Exeter House in London, to serve as his personal physician. In London, Locke resumed his medical studies under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major effect on Locke's natural philosophical thinking—an effect that would become evident in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Locke's medical knowledge was put to the test when Ashley's liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the advice of several physicians and was probably instrumental in persuading Ashley to undergo surgery (then life-threatening in itself) to remove the cyst. Ashley survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

During this time, Locke served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.

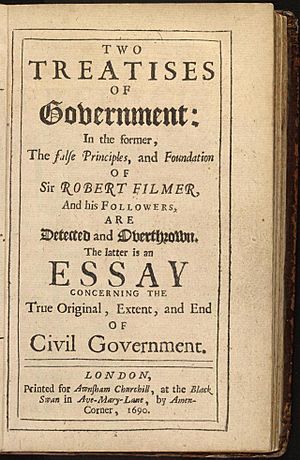

Ashley, as a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke's political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Ashley became Lord Chancellor in 1672 (Ashley being created 1st Earl of Shaftesbury in 1673). Following Shaftesbury's fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks. He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury's political fortunes took a brief positive turn. Around this time, most likely at Shaftesbury's prompting, Locke composed the bulk of the Two Treatises of Government. While it was once thought that Locke wrote the Treatises to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was composed well before this date. The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy (particularly as espoused by Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are today considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

The Netherlands

Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the scheme. The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends "from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza's small group of loyal confidants. [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677.] Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who... insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone." While she says that "Locke's strong empiricist tendencies" would have "disinclined him to read a grandly metaphysical work such as Spinoza's Ethics, in other ways he was deeply receptive to Spinoza's ideas, most particularly to the rationalist's well thought out argument for political and religious tolerance and the necessity of the separation of church and state." In the Netherlands, Locke had time to return to his writing, spending a great deal of time working on the Essay Concerning Human Understanding and composing the Letter on Toleration.

Return to England

Locke did not return home until after the Glorious Revolution. Locke accompanied Mary II back to England in 1689. The bulk of Locke's publishing took place upon his return from exile—his aforementioned Essay Concerning Human Understanding, the Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration all appearing in quick succession.

Locke's close friend Lady Masham invited him to join her at Otes, the Mashams' country house in Essex. Although his time there was marked by variable health from asthma attacks, he nevertheless became an intellectual hero of the Whigs. During this period he discussed matters with such figures as John Dryden and Isaac Newton.

Death

He died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of the village of High Laver, east of Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691. Locke never married nor had children.

Events that happened during Locke's lifetime include the English Restoration, the Great Plague of London, the Great Fire of London, and the Glorious Revolution. He did not see the Act of Union of 1707, but the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal union throughout his lifetime. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy were in their infancy during Locke's time.

Philosophy

Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy, in particular on modern liberalism. His arguments concerning liberty and the social contract later influenced the written works of Thomas Jefferson.

Locke's theory of association heavily influenced the subject matter of modern psychology. At the time, Locke's recognition of two types of ideas, simple and complex—and, more importantly, their interaction through association—inspired other philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and apply it to explain how humans gain knowledge in the physical world.

Locke thought the state's borders and the functioning and enforcement of the existence of the state and its constitution were metaphysically tied to "the natural rights of the individual", and this inspired future liberal politicians and philosophers.

Slavery and child labour

Although Locke wrote against slavery in general, he was an investor and beneficiary of the slave-trading Royal Africa Company. In addition, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy and gave Carolinian planters absolute power over their enslaved chattel property; the constitutions pledged that "every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves".

Locke also supported child labour, which was an intrinsic part of all pre-industrial societies. He suggested that "working schools" be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be "from infancy [three years old] inured to work". He went on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they would be profitable for the parish, but also that they would instil a good work ethic in the children.

Government

Locke's political theory was founded upon that of social contract. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature is characterised by reason and tolerance. Like Hobbes, however, Locke believed that human nature allows people to be selfish. This is apparent with the introduction of currency. In a natural state, all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his "life, health, liberty, or possessions".

Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society. Locke also advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States.

Accumulation of wealth

Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating property. Locke implies that government would function to moderate the conflict between the unlimited accumulation of property and a more nearly equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem.

Ideas

Economics

On price theory

Locke's general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory.

Locke claims that, as far as money is concerned, the demand for it is exclusively regulated by its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains demand for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation, such as of land, which has value because "by its constant production of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income". He considers the demand for money as almost the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether money is wanted as medium of exchange.

Monetary thoughts

Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a counter to measure value, and as a pledge to lay claim to goods. He believes that silver and gold, as opposed to paper money, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which issues it.

Since the world money stock grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its own stock.

Theory of value and property

Locke uses the concept of property in both broad and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to material goods. He argues that property is a natural right that is derived from labour. In Chapter V of his Second Treatise, Locke argues that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce such goods—"at least where there is enough [land], and as good, left in common for others" (para. 27)—or to use property to produce goods beneficial to human society.

Locke states in his Second Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a labour theory of value, Locke developed a labour theory of property, whereby ownership of property is created by the application of labour.

The human mind

The self

Locke defines the self as "that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, made up of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends". He does not, however, wholly ignore "substance", writing that "the body too goes to the making the man".

Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education is an outline on how to educate the mind. Drawing on thoughts expressed in letters written to Mary Clarke and her husband about their son, he expresses the belief that education makes the man—or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty cabinet":

I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education.

Locke also wrote that "the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences". He argues that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other".

This theory came to be called associationism, going on to strongly influence 18th-century thought, particularly educational theory, as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines.

Library

Manuscripts, books and treatises

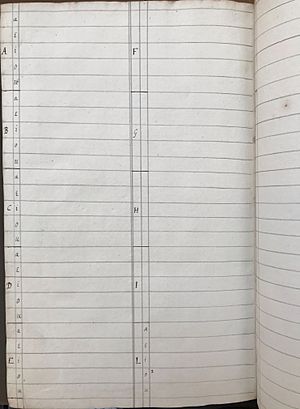

Locke was an assiduous book collector and notetaker throughout his life. By his death in 1704, Locke had amassed a library of more than 3,000 books, a significant number in the seventeenth century. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Locke took care to catalogue and preserve his library, and his will made specific provisions for how his library was to be distributed after his death. Locke's will offered Lady Masham the choice of "any four folios, eight quartos and twenty books of less volume, which she shall choose out of the books in my Library." Locke also gave six titles to his "good friend" Anthony Collins, but Locke bequeathed the majority of his collection to his cousin Peter King (later Lord King) and to Lady Masham's son, Francis Cudworth Masham.

Francis Masham was promised one "moiety" (half) of Locke's library when he reached "the age of one and twenty years." The other "moiety" of Locke's books, along with his manuscripts, passed to his cousin King. Over the next two centuries, the Masham portion of Locke's library was dispersed. The manuscripts and books left to King, however, remained with King's descendants (later the Earls of Lovelace), until most of the collection was bought by the Bodleian Library, Oxford in 1947. Another portion of the books Locke left to King was discovered by the collector and philanthropist Paul Mellon in 1951. Mellon supplemented this discovery with books from Locke's library which he bought privately, and in 1978, he transferred his collection to the Bodleian. The holdings in the Locke Room at the Bodleian have been a valuable resource for scholars interested in Locke, his philosophy, practices for information management, and the history of the book.

Many of the books still contain Locke's signature, which he often made on the pastedowns of his books. Many also include Locke's marginalia.

The printed books in Locke's library reflected his various intellectual interests as well as his movements at different stages of his life. Locke travelled extensively in France and the Netherlands during the 1670s and 1680s, and during this time he acquired many books from the continent. Only half of the books in Locke's library were printed in England, while close to 40% came from France and the Netherlands. These books cover a wide range of subjects. According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke's library were theology (23.8% of books), medicine (11.1%), politics and law (10.7%), and classical literature (10.1%). The Bodleian library currently holds more than 800 of the books from Locke's library. These include Locke's copies of works by several of the most influential figures of the seventeenth century.

In addition to books owned by Locke, the Bodleian also possesses more than 100 manuscripts related to Locke or written in his hand. Like the books in Locke's library, these manuscripts display a range of interests and provide different windows into Locke's activity and relationships.

Writing

List of major works

- 1689. A Letter Concerning Toleration.

- 1690. A Second Letter Concerning Toleration

- 1692. A Third Letter for Toleration

- 1689/90. Two Treatises of Government (published throughout the 18th century by London bookseller Andrew Millar by commission for Thomas Hollis)

- 1689/90. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- 1691. Some Considerations on the consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money

- 1693. Some Thoughts Concerning Education

- 1695. The Reasonableness of Christianity, as Delivered in the Scriptures

- 1695. A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity

Major posthumous manuscripts

- 1660. First Tract of Government (or the English Tract)

- c.1662. Second Tract of Government (or the Latin Tract)

- 1664. Questions Concerning the Law of Nature.

- 1667. Essay Concerning Toleration

- 1706. Of the Conduct of the Understanding

- 1707. A paraphrase and notes on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Ephesians

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Locke para niños

In Spanish: John Locke para niños