David Hume facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

David Hume

|

|

|---|---|

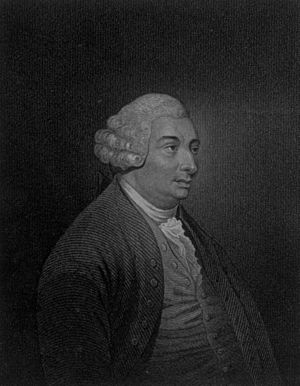

David Hume by Allan Ramsay, 1754

|

|

| Born |

David Home

7 May NS [26 April OS] 1711 Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Died | 25 August 1776 (aged 65) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

List

|

|

Influenced

|

|

David Hume (/hjuːm/; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, historian, economist, librarian, and essayist.

His philosophy of religion, including his rejection of miracles and the argument from design for God's existence, were especially controversial for their time.

Contents

Early life

Hume was born on 26 April 1711 (Old Style), as David Home, in a tenement on the north side of Edinburgh's Lawnmarket. He was the second of two sons born to Catherine Home (née Falconer), daughter of Sir David Falconer of Newton and his wife Mary Falconer (née Norvell), and Joseph Home of Chirnside in the County of Berwick, an advocate of Ninewells. Joseph died just after David's second birthday. Catherine, who never remarried, raised the two brothers and their sister on her own.

Hume changed his family name's spelling in 1734, as the surname 'Home' (pronounced as 'Hume') was not well-known in England.

Hume attended the University of Edinburgh at an unusually early age—either 12 or possibly as young as 10—at a time when 14 was the typical age. He did not graduate.

Career

Although having noble ancestry, at age 25 Hume had no source of income and no learned profession. As was common at his time, he became a merchant's assistant, despite having to leave his native Scotland. He travelled via Bristol to La Flèche in Anjou, France. There he had frequent discourse with the Jesuits of the College of La Flèche.

Hume was derailed in his attempts to start a university career by protests over his alleged "atheism". He worked for four years on his first major work, A Treatise of Human Nature, completing it in 1738 at age 28. He found literary success in his lifetime as an essayist, and a career as a librarian at the University of Edinburgh. His tenure there, and the access to research materials it provided, resulted in Hume's writing the massive six-volume The History of England, which became a bestseller and made Hume a wealthy man who no longer had to take up salaried work for others. It was influential for nearly a century, despite competition from imitations by Smollett (1757), Goldsmith (1771) and others. By 1894, there were at least 50 editions as well as abridgements for students, and illustrated pocket editions, probably produced specifically for women.

Later life

From 1763 to 1765, Hume was invited to attend Lord Hertford in Paris, where he became secretary to the British embassy.

In 1765, Hume served as British Chargé d'affaires, writing "despatches to the British Secretary of State".

In 1767, Hume was appointed Under Secretary of State for the Northern Department. Here, he wrote that he was given "all the secrets of the Kingdom". In 1769 he returned to James' Court in Edinburgh, where he would live from 1771 until his death in 1776.

Death

Diarist and biographer James Boswell saw Hume a few weeks before his death from a form of abdominal cancer. Hume asked that his body be interred in a "simple Roman tomb", requesting in his will that it be inscribed only with his name and the year of his birth and death, "leaving it to Posterity to add the Rest".

David Hume died at the southwest corner of St. Andrew's Square in Edinburgh's New Town, at what is now 21 Saint David Street.

His tomb stands, as he wished it, on the southwestern slope of Calton Hill, in the Old Calton Cemetery.

Impressions and ideas

A central doctrine of Hume's philosophy is that the mind consists of perceptions, which divide into two categories: impressions and ideas. Hume distinguishes impressions from ideas on the basis of their force, liveliness, and vivacity. Ideas are therefore "faint" impressions. For example, experiencing the painful sensation of touching a hot pan's handle is more forceful than simply thinking about touching a hot pan. According to Hume, impressions are meant to be the original form of all our ideas. Thus, he argued against the existence of innate ideas, positing that all human knowledge derives solely from experience.

Humes also held that passions rather than reason govern human behaviour, famously proclaiming that "Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions."

Problem of miracles

Hume argues that we should not believe miracles have occurred and that they do not therefore provide us with any reason to think God exists. He points out that people often lie, and they have good reasons to lie about miracles occurring either because they believe they are doing so for the benefit of their religion or because of the fame that results. Furthermore, people by nature enjoy relating miracles they have heard without caring for their veracity and thus miracles are easily transmitted even when false. Also, Hume notes that miracles seem to occur mostly in "ignorant and barbarous nations" and times, and the reason they do not occur in the civilised societies is such societies are not awed by what they know to be natural events. Finally, the miracles of each religion argue against all other religions and their miracles, and so even if a proportion of all reported miracles across the world fit Hume's requirement for belief, the miracles of each religion make the other less likely.

Political theory

Hume is considered a founding father of conservatism.

He offered his view on the best type of society in an essay titled "Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth". In it he argued that in the best form of government there is a strict separation of powers and decentralisation. Hume advocated for extending the franchise to anyone who held property of value and limiting the power of the clergy. The system of the Swiss militia was proposed as the best form of protection. Elections were to take place on an annual basis and representatives were to be unpaid.

Contributions to economic thought

Hume introduced several new ideas around which the "classical economics" of the 18th century was built. This includes ideas on private property, inflation, and foreign trade.

Hume believed that private property is not a natural right. He argues it is justified, because resources are limited. Private property would be an unjustified, "idle ceremonial," if all goods were unlimited and available freely. Hume also believed in an unequal distribution of property, because perfect equality would destroy the ideas of thrift and industry. Perfect equality would thus lead to impoverishment.

David Hume anticipated modern monetarism. He contributed to the theory of quantity and of interest rate. Hume has been credited with being the first to prove that, on an abstract level, there is no quantifiable amount of nominal money that a country needs to thrive. He understood that there was a difference between nominal and real money.

Legacy

Due to Hume's vast influence on contemporary philosophy, a large number of approaches in contemporary philosophy and cognitive science are today called "Humean."

Attention to Hume's philosophical works grew after the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (1783), credited Hume with awakening him from his "dogmatic slumber."

Interesting facts about David Hume

- At age 18 or so, Hume set out to spend a minimum of 10 years reading and writing. He soon came to the verge of a mental breakdown, first starting with a coldness—which he attributed to a "Laziness of Temper"—that lasted about nine months. Later, some scurvy spots broke out on his fingers, persuading Hume's physician to diagnose Hume as suffering from the "Disease of the Learned".

- Hume never married and lived partly at his Chirnside family home in Berwickshire, which had belonged to the family since the 16th century.

- He had little respect for the professors of his time, telling a friend in 1735 that "there is nothing to be learnt from a Professor, which is not to be met with in Books".

- Hume considered his two late works, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding and An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, as his greatest literary and philosophical achievements. He would ask of his contemporaries to judge him on the merits of the later texts alone.

- Although many scholars today regard A Treatise of Human Nature as Hume's most important work and one of the most important books in Western philosophy, at the time of its publication it was described as "abstract and unintelligible".

- In the last year of his life, Hume wrote an extremely brief autobiographical essay titled "My Own Life", summing up his entire life in "fewer than 5 pages"; it contains many interesting judgments that have been of enduring interest to subsequent readers of Hume.

- Hume was obese and well known for a fondness for good port and cheese.

- In the 1770s, Hume was critical of British policies toward the American colonies and advocated for American independence.

- Immanuel Kant credited Hume as the inspiration who had awakened him from his "dogmatic slumbers."

- Hume's nephew and namesake, David Hume of Ninewells (1757–1838), was a co-founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783. He was a Professor of Scots Law at Edinburgh University and rose to be Principal Clerk of Session in the Scottish High Court and Baron of the Exchequer. He is buried with his uncle in Old Calton Cemetery.

- Albert Einstein, in 1915, wrote that he was inspired by Hume's positivism when formulating his theory of special relativity.

Works

- 1734. A Kind of History of My Life. – MSS 23159 National Library of Scotland.

- A letter to an unnamed physician, asking for advice about "the Disease of the Learned" that then afflicted him. Here he reports that at the age of eighteen "there seem'd to be open'd up to me a new Scene of Thought" that made him "throw up every other Pleasure or Business" and turned him to scholarship.

- 1739–1740. A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects.

- Hume intended to see whether the Treatise of Human Nature met with success, and if so, to complete it with books devoted to Politics and Criticism. However, as Hume explained, "It fell dead-born from the press, without reaching such distinction as even to excite a murmur among the zealots" and so his further project was not completed.

- 1740. An Abstract of a Book lately Published: Entitled A Treatise of Human Nature etc.

- Anonymously published, but almost certainly written by Hume in an attempt to popularise his Treatise. This work is of considerable philosophical interest as it spells out what Hume considered "The Chief Argument" of the Treatise, in a way that seems to anticipate the structure of the Enquiry concerning Human Understanding.

- 1741. Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary (2st ed.)

- A collection of pieces written and published over many years, though most were collected together in 1753–54. Many of the essays are on politics and economics; other topics include aesthetic judgement, love, marriage and polygamy, and the demographics of ancient Greece and Rome. The Essays show some influence from Addison's Tatler and The Spectator, which Hume read avidly in his youth.

- 1745. A Letter from a Gentleman to His Friend in Edinburgh: Containing Some Observations on a Specimen of the Principles concerning Religion and Morality, said to be maintain'd in a Book lately publish'd, intituled A Treatise of Human Nature etc.

- Contains a letter written by Hume to defend himself against charges of atheism and scepticism, while applying for a chair at Edinburgh University.

- 1742. "Of Essay Writing."

- 1748. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding.

- Contains reworking of the main points of the Treatise, Book 1, with the addition of material on free will (adapted from Book 2), miracles, the Design Argument, and mitigated scepticism. Of Miracles, section X of the Enquiry, was often published separately.

- 1751. An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals.

- A reworking of material on morality from Book 3 of the Treatise, but with a significantly different emphasis. It "was thought by Hume to be the best of his writings."

- 1752. Political Discourses (part II of Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary within the larger Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects, vol. 1).

- Included in Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects (1753–56) reprinted 1758–77.

- 1752–1758. Political Discourses/Discours politiques

- 1757. Four Dissertations – includes 4 essays:

- "The Natural History of Religion"

- "Of the Passions"

- "Of Tragedy"

- "Of the Standard of Taste"

- 1754–1762. The History of England – sometimes referred to as The History of Great Britain.

- More a category of books than a single work, Hume's history spanned "from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution of 1688" and went through over 100 editions. Many considered it the standard history of England in its day.

- 1760. "Sister Peg"

- Hume claimed to have authored an anonymous political pamphlet satirizing the failure of the British Parliament to create a Scottish militia in 1760. Although the authorship of the work is disputed, Hume wrote Dr. Alexander Carlyle in early 1761 claiming authorship. The readership of the time attributed the work to Adam Ferguson, a friend and associate of Hume's who has been sometimes called "the founder of modern sociology." Some contemporary scholars concur in the judgment that Ferguson, not Hume, was the author of this work.

- 1776. "My Own Life."

- Penned in April, shortly before his death, this autobiography was intended for inclusion in a new edition of Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects. It was first published by Adam Smith, who claimed that by doing so he had incurred "ten times more abuse than the very violent attack I had made upon the whole commercial system of Great Britain."

- 1779. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion.

- Published posthumously by his nephew, David Hume the Younger. Being a discussion among three fictional characters concerning the nature of God, and is an important portrayal of the argument from design. Despite some controversy, most scholars agree that the view of Philo, the most sceptical of the three, comes closest to Hume's own.

See also

In Spanish: David Hume para niños

In Spanish: David Hume para niños