James A. Garfield facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

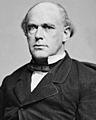

James A. Garfield

|

|

|---|---|

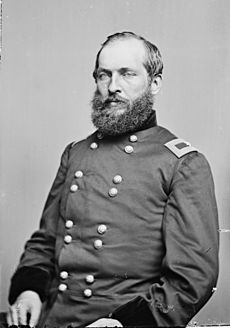

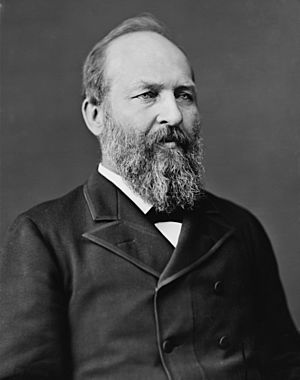

Garfield in 1881

|

|

| 20th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

|

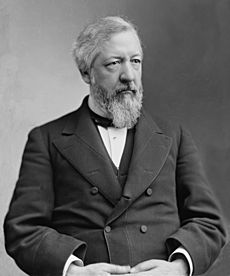

| Vice President | Chester A. Arthur |

| Preceded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Succeeded by | Chester A. Arthur |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 19th district |

|

| In office March 4, 1863 – November 8, 1880 |

|

| Preceded by | Albert G. Riddle |

| Succeeded by | Ezra B. Taylor |

| Chair of the House Appropriations Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1871 – March 4, 1875 |

|

| Preceded by | Henry L. Dawes |

| Succeeded by | Samuel J. Randall |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 26th district |

|

| In office January 2, 1860 – August 21, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | George P. Ashmun |

| Succeeded by | Lucius V. Bierce |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

James Abram Garfield

November 19, 1831 Moreland Hills, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | September 19, 1881 (aged 49) Elberon, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | James A. Garfield Memorial |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7, including Hal, James, and Abram |

| Education |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881, until his death six months later—two months after he was shot by assassin Charles J. Guiteau. A lawyer and Civil War general, Garfield served nine terms in the United States House of Representatives and is, to date, the only sitting member of the House to be elected president. Before his candidacy for the White House, he had been elected to the U.S. Senate by the Ohio General Assembly—a position he declined when he became president-elect.

Contents

Childhood and early life

James Abram Garfield was born on November 19, 1831. He was the youngest of five children of Abram Garfield and Eliza Ballou. The family lived in poverty in a log cabin in Orange Township, now Moreland Hills, Ohio.

Garfield's father died in 1833, and James was raised in poverty in a household led by his strong-willed mother. He was her favorite child and the two remained close for the rest of his life. Garfield enjoyed his mother's stories about his ancestry, especially those about his Welsh great-great-grandfathers and an ancestor who served as a knight of Caerphilly Castle.

Garfield later said of his childhood, "I lament that I was born to poverty, and in this chaos of childhood, seventeen years passed before I caught any inspiration ... a precious 17 years when a boy with a father and some wealth might have become fixed in manly ways."

Education and marriage

Garfield attended Geauga Seminary from 1848 to 1850 and learned academic subjects for which he had not previously had time. Geauga was coeducational, and Garfield was attracted to one of his classmates, Lucretia Rudolph, whom he married in 1858. The couple had seven children, five of whom survived infancy.

After he left Geauga, Garfield worked for a year at various jobs, including teaching jobs. From 1851 to 1854, he attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later named Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio, a school run by the Disciples. While there, he was most interested in the study of Greek and Latin, but was inclined to learn about and discuss any new thing he encountered. Securing a position on entry as janitor, he obtained a teaching position while he was still a student there.

By 1854, Garfield had learned all the Institute could teach him and was a full-time teacher. Garfield then enrolled at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, as a third-year student; he received credit for two years' study at the Institute after passing a cursory examination.

Garfield graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Williams in August 1856, was named salutatorian, and spoke at the commencement.

Early career

Upon his return to Ohio, Garfield studied law and became an attorney. Garfield was elected as a Republican member of the Ohio State Senate in 1859, serving until 1861.

Civil War

After Abraham Lincoln's election as president, several Southern states announced their secession from the Union to form a new government, the Confederate States of America. Garfield read military texts while anxiously awaiting the war effort, which he regarded as a holy crusade against the Slave Power. In April 1861, the rebels bombarded Fort Sumter, one of the South's last federal outposts, beginning the Civil War. Although he had no military training, Garfield knew his place was in the Union Army.

He was quickly promoted to a major general in the Union Army, and fought in the battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh, and Chickamauga.

Congressional career

Garfield was elected to Congress in 1862 to represent Ohio's 19th district. Throughout his congressional service, he firmly supported the gold standard and gained a reputation as a skilled orator. Garfield supported black suffrage as firmly as he supported abolition.

Garfield hailed the ratification of the 15th Amendment in 1870 as a triumph and favored Georgia's readmission to the Union as a matter of right, not politics. An influential Republican, Garfield said, "[The] Fifteen Amendment confers on the African race the care of its own destiny. It places their fortunes in their own hands." In 1871, Congress took up the Ku Klux Klan Act, which was designed to combat attacks on African Americans' suffrage rights. Garfield opposed the act, saying, "I have never been more perplexed by a piece of legislation." He was torn between his indignation at the Klan, whom he called "terrorists".

Tariffs had been raised to high levels during the Civil War. Afterward, Garfield, who made a close study of financial affairs, advocated moving toward free trade.

Starting in January 1870, Garfield, then chairman of the House Banking Committee, led an investigation into the Black Friday Gold Panic scandal. Garfield's investigation showed that the scandal was enabled by the greenbacks that financed the speculation.

Presidency (1881)

In the 1880 presidential election, Garfield conducted a low-key front porch campaign and narrowly defeated the Democratic nominee, Winfield Scott Hancock.

Refinance of national debt

Garfield ordered the Secretary of the Treasury William Windom to refund (refinance) the national debt by calling in outstanding U.S. bonds paying 6% interest. Holders would have the option of accepting cash or new bonds at 3%, closer to the interest rates of the time. Taxpayers were saved an estimated $10 million. By comparison, federal expenditures in 1881 were below $261 million.

Reforms

Grant and Hayes had both advocated civil service reform, and by 1881 such reform associations had organized with renewed energy across the nation. Garfield sympathized with them, believing the spoils system damaged the presidency and often eclipsed more important concerns. Some reformers became disappointed when Garfield promoted limited tenure only to minor office seekers and gave appointments to his old friends.

Corruption in the post office also cried out for reform. In April 1880, there had been a congressional investigation of corruption in the Post Office Department, where profiteering rings allegedly stole millions of dollars, securing bogus mail contracts on star routes. After obtaining contracts with the lowest bid, costs to run the mail routes would be escalated and profits would be divided among ring members. Shortly after taking office, Garfield received word of postal corruption by an alleged star route ringleader, Assistant Postmaster General Thomas J. Brady. Garfield demanded Brady's resignation and ordered prosecutions that ended in trials for conspiracy. When told that his party, including his campaign manager, Stephen W. Dorsey, was involved, Garfield directed that the corruption in the Post Office be rooted out "to the bone", regardless of where it might lead. Brady resigned and was indicted for conspiracy, though jury trials in 1882 and 1883 found Brady not guilty.

Civil rights and education

Garfield believed the key to improving the state of African American civil rights was government supported education. During Reconstruction, freedmen had gained citizenship and suffrage, which enabled them to participate in government, but Garfield believed their rights were being eroded by Southern white resistance and illiteracy, and he was concerned that blacks would become America's permanent "peasantry". He proposed a "universal" education system funded by the federal government. In February 1866, Garfield and Ohio School Commissioner Emerson Edward White drafted a bill for the National Department of Education. They believed that through the use of statistics they could push the US Congress to establish a federal agency for school reform. But Congress and the northern white public had lost interest in African-American rights, and Congress did not pass federal funding for universal education during Garfield's term. Garfield also worked to appoint several African Americans to prominent positions: Frederick Douglass, recorder of deeds in Washington; Robert Elliot, special agent to the Treasury; John M. Langston, Haitian minister; and Blanche K. Bruce, register to the Treasury. Garfield believed Southern support for the Republican Party could be gained by "commercial and industrial" interests rather than race issues and began to reverse Hayes's policy of conciliating Southern Democrats. He appointed William H. Hunt, a carpetbagger Republican from Louisiana, as Secretary of the Navy. To break the hold of the resurgent Democratic Party in the Solid South, Garfield took patronage advice from Virginia Senator William Mahone of the biracial independent Readjuster Party, hoping to add the independents' strength to the Republicans' there.

Garfield had little foreign policy experience, so he leaned heavily on Blaine. They agreed on the need to promote freer trade, especially within the Western Hemisphere. Garfield and Blaine believed increasing trade with Latin America would be the best way to keep the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from dominating the region. And by encouraging exports, they believed they could increase American prosperity. Garfield authorized Blaine to call for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations and to serve as a forum for talks on increasing trade.

At the same time, they hoped to negotiate a peace in the War of the Pacific then being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Blaine favored a resolution that would result in Peru yielding no territory, but Chile by 1881 had occupied the Peruvian capital of Lima, and rejected any settlement that restored the previous status quo.

Garfield sought to expand American influence in other areas, calling for renegotiation of the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty to allow the United States to construct a canal through Panama without British involvement and attempting to reduce British influence in the strategically located Kingdom of Hawaii. Garfield's and Blaine's plans for the United States' involvement in the world stretched even beyond the Western Hemisphere, as he sought commercial treaties with Korea and Madagascar. Garfield also considered enhancing U.S. military strength abroad, asking Navy Secretary Hunt to investigate the navy's condition with an eye toward expansion and modernization. In the end, these ambitious plans came to nothing after Garfield was assassinated. Nine countries had accepted invitations to the Pan-American conference, but the invitations were withdrawn in April 1882 after Blaine resigned from the cabinet and Arthur, Garfield's successor, cancelled the conference. Naval reform continued under Arthur, on a more modest scale than Garfield and Hunt had envisioned, ultimately ending in the construction of the Squadron of Evolution.

Assassination

Guiteau and shooting

Charles J. Guiteau had followed various professions in his life, but in 1880 had determined to gain federal office by supporting what he expected would be the winning Republican ticket. He composed a speech, "Garfield vs. Hancock", and got it printed by the Republican National Committee. One means of persuading the voters in that era was through orators expounding on the candidate's merits, but with the Republicans seeking more famous men, Guiteau received few opportunities to speak. On one occasion, according to Kenneth D. Ackerman, Guiteau was unable to finish his speech due to nerves. Guiteau, who considered himself a Stalwart, deemed his contribution to Garfield's victory sufficient to justify his appointment to the position of consul in Paris, despite the fact that he spoke no French, nor any foreign language. One medical expert has since described Guiteau as possibly a narcissistic schizophrenic; neuroscientist Kent Kiehl assessed him as a clinical psychopath.

One of Garfield's more wearying duties was seeing office-seekers, and he saw Guiteau at least once. White House officials suggested to Guiteau that he approach Blaine, as the consulship was within the Department of State. Blaine also saw the public regularly, and Guiteau became a regular at these sessions. Blaine, who had no intention of giving Guiteau a position he was unqualified for and had not earned, simply said the deadlock in the Senate over Robertson's nomination made it impossible to consider the Paris consulship, which required Senate confirmation. Once the New York senators had resigned, and Robertson had been confirmed as Collector, Guiteau pressed his claim, and Blaine told him he would not receive the position.

Guiteau came to believe he had lost the position because he was a Stalwart. He decided the only way to end the Republican Party's internecine warfare was for Garfield to die—though he had nothing personal against the president. Arthur's succession would restore peace, he felt, and lead to rewards for fellow Stalwarts, including Guiteau.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln was deemed a fluke due to the Civil War, and Garfield, like most people, saw no reason the president should be guarded; his movements and plans were often printed in the newspapers. Guiteau knew Garfield would leave Washington for a cooler climate on July 2, 1881, and made plans to kill him before then. He purchased a gun he thought would look good in a museum, and followed Garfield several times, but each time his plans were frustrated, or he lost his nerve. His opportunities dwindled to one—Garfield's departure by train for New Jersey on the morning of July 2.

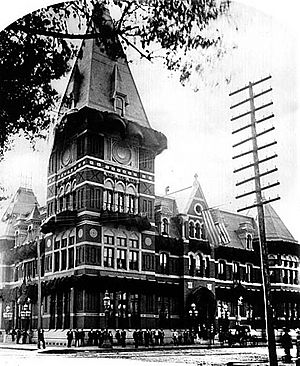

Guiteau concealed himself by the ladies' waiting room at the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, from where Garfield was scheduled to depart. Most of Garfield's cabinet planned to accompany him at least part of the way. Blaine, who was to remain in Washington, came to the station to see him off. The two men were deep in conversation and did not notice Guiteau before he took out his revolver and shot Garfield. Guiteau attempted to leave the station, but was quickly captured. As Blaine recognized him, Guiteau was led away, and said, "I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President." News of his motivation to benefit the Stalwarts reached many with the news of the shooting, causing rage against that faction.

Guiteau was indicted on October 14, 1881, for the murder of the president. During his trial, Guiteau declared that he was not responsible for Garfield's death, admitting to the shooting but not the killing. After a chaotic trial in which Guiteau often interrupted and argued, and in which his counsel used the insanity defense, the jury found him guilty on January 25, 1882, and he was sentenced to death by hanging. Guiteau was executed on June 30, 1882.

Funeral, memorials and commemorations

Garfield's funeral train left Long Branch on the same special track that had brought him there, traveling over tracks blanketed with flowers and past houses adorned with flags. His body was transported to the Capitol and then continued on to Cleveland for burial. Shocked by his death, Marine Band leader John Philip Sousa composed the march "In Memoriam", which was played when Garfield's body was received in Washington, D.C. More than 70,000 citizens, some waiting over three hours, passed by Garfield's coffin as his body lay in state from September 21 to 23, 1881, at the United States Capitol rotunda; on September 25, in Cleveland, Garfield's casket was paraded down Euclid Avenue from Wilson Avenue to Public Square, with those in attendance including former presidents Grant and Hayes, and Generals William Sherman, Sheridan and Hancock. More than 150,000—a number equal to the city's population—likewise paid their respects, and Sousa's march was again played. Garfield's body was temporarily interred in the Schofield family vault in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery until his permanent memorial was built.

Memorials to Garfield were erected across the country. On April 10, 1882, seven months after Garfield's death, the U.S. Post Office Department issued a postage stamp in his honor. In 1884, sculptor Frank Happersberger completed a monument on the grounds of the San Francisco Conservatory of Flowers. In 1887, the James A. Garfield Monument was dedicated in Washington. Another monument, in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, was erected in 1896.

On May 19, 1890, Garfield's body was permanently interred, with great solemnity and fanfare, in a mausoleum in Lake View Cemetery. Attending the dedication ceremonies were former President Hayes, President Benjamin Harrison, and future president William McKinley. Garfield's Treasury Secretary, William Windom, also attended. Harrison said Garfield was always a "student and instructor" and that his life works and death would "continue to be instructive and inspiring incidents in American history". Three panels on the monument display Garfield as a teacher, Union major general, and orator; another shows him taking the presidential oath, and a fifth shows his body lying in state at the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C.

Garfield's murder by a deranged office-seeker awakened public awareness of the need for civil service reform legislation. Senator George H. Pendleton, a Democrat from Ohio, launched a reform effort that resulted in the Pendleton Act in January 1883. This act reversed the "spoils system" where office seekers paid up or gave political service to obtain or keep federally appointed positions. Under the act, appointments were awarded on merit and competitive examination. To ensure the reform was implemented, Congress and Arthur established and funded the Civil Service Commission. The Pendleton Act, however, covered only 10% of federal government workers. For Arthur, previously known for having been a "veteran spoilsman", civil service reform became his most noteworthy achievement.

A marble statue of Garfield by Charles Niehaus was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol in Washington D.C., a gift from the State of Ohio in 1886.

Garfield is honored with a life-size bronze sculpture inside the Cuyahoga County Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in Cleveland, Ohio.

On March 2, 2019, the National Park Service erected exhibit panels in Washington to mark the site of his assassination.

-

Lawnfield, Garfield National Historic Site, location of the "front porch campaign"

-

Garfield Memorial at Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio

-

James A. Garfield Monument in Washington, D.C.

Legacy and historical view

For a few years after his assassination, Garfield's life story was seen as an exemplar of the American success story—that even the poorest boy might someday become President of the United States.

Garfield's presidency saw a promising start before its untimely end. Historian Justus D. Doenecke chronicles his achievements: "by winning a victory over the Stalwarts, he enhanced both the power and prestige of his office. As a man, he was intelligent, sensitive, and alert, and his knowledge of how government worked was unmatched."

James A. Garfield quotes

- “Things don’t turn up in this world until somebody turns them up.”

- “The men who succeed best in public life are those who take the risk of standing by their own convictions.”

- “Next in importance to freedom and justice is popular education, without which neither freedom nor justice can be permanently maintained.”

- “I mean to make myself a man, and if I succeed in that, I shall succeed in everything else.”

- “Be fit for more than the thing you are now doing. Let everyone know that you have a reserve in yourself,— that you have more power than you are now using. If you are not too large for the place you occupy, you are too small for it.”

- “The chief duty of government is to keep the peace and stand out of the sunshine of the people.”

- “I would rather be beaten in Right than succeed in Wrong.”

Interesting facts about James A. Garfield

- James was named after his elder brother who had died in infancy.

- Poor and fatherless, Garfield was mocked by his peers and sought escape through voracious reading.

- Garfield left home at age 16 in 1847 and found work on a canal boat, managing the mules that pulled it.

- Garfield excelled as a student and was especially interested in languages and elocution.

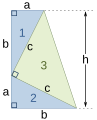

- Garfield's aptitude for mathematics extended to a notable proof of the Pythagorean theorem, which he published in 1876. Mathematics historian William Dunham wrote that Garfield's trapezoid work was "really a very clever proof."

- Garfield favored the abolition of slavery and supported the confiscation of Southern plantations and even exile or execution of rebellion leaders as a means to ensure a permanent end to slavery.

- Garfield did not consider Lincoln very worthy of reelection, but there seemed to be no viable alternative, "He will probably be the man, though I think we could do better." In the following years, Garfield had more praise for Lincoln; a year after Lincoln's death, Garfield said, "Greatest among all these developments were the character and fame of Abraham Lincoln," and in 1878 he called Lincoln "one of the few great rulers whose wisdom increased with his power".

Images for kids

-

General William S. Rosecrans

-

Salmon P. Chase was Garfield's ally until Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial.

-

Garfield Monument, by the Capitol, where he served almost twenty years

-

President U.S. GrantMathew Brady 1870

-

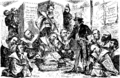

Editorial cartoon: Uncle Sam directs U.S. Senators and Representatives implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scheme to commit Hara-Kiri.

-

Garfield (second from right in the row of commissioners just below the gallery) served on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election. Painting by Cornelia Adele Strong Fassett.

-

Following Grant's defeat for the nomination Puck magazine satirized Robert E. Lee's surrender to him at Appomattox by depicting Grant giving up his sword to Garfield.

See also

In Spanish: James A. Garfield para niños

In Spanish: James A. Garfield para niños