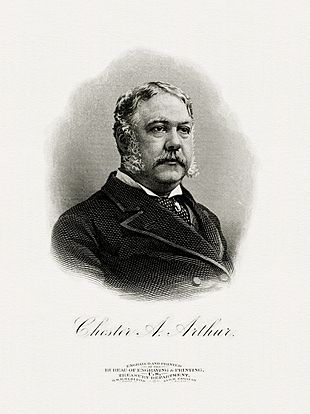

Chester A. Arthur facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Chester Alan Arthur

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 21st President of the United States | |

| In office September 19, 1881 – March 3, 1885 |

|

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | James A. Garfield |

| Succeeded by | Grover Cleveland |

| 20th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

|

| President | James A. Garfield |

| Preceded by | William A. Wheeler |

| Succeeded by | Thomas A. Hendricks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 5, 1829 Fairfield, Vermont |

| Died | November 18, 1886 (aged 57) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Ellen Lewis Herndon Arthur |

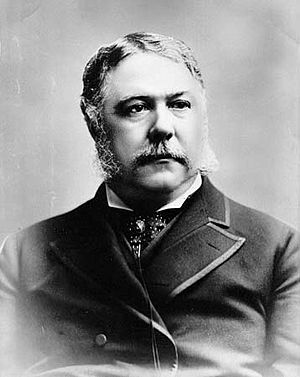

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. Previously the 20th vice president, he succeeded to the presidency upon the death of President James A. Garfield in September 1881, two months after Garfield was shot by an assassin.

Contents

Early life and family

Arthur's father, William Arthur, was born in 1796 in Dreen, Cullybackey, County Antrim, Ireland to a Presbyterian family of Scots-Irish descent. Malvina Stone met William Arthur when Arthur was teaching school in Dunham, Quebec, near the Vermont border. They married in Dunham on April 12, 1821, soon after meeting. The Arthurs moved to Vermont after the birth of their first child, Regina.

Chester Alan Arthur was born in 1829 in Fairfield, Vermont and grew up in upstate New York; he was the fifth of nine children. He was named "Chester" after Chester Abell, the physician and family friend who assisted in his birth, and "Alan" for his paternal grandfather. The family remained in Fairfield until 1832, when William Arthur's profession took them to churches in several towns in Vermont and upstate New York. The family finally settled in the Schenectady, New York area.

Arthur had seven siblings who lived to adulthood:

- Regina (1822–1910), the wife of William G. Caw, a grocer, banker, and community leader of Cohoes, New York who served as town supervisor and village trustee

- Jane (1824–1842)

- Almeda (1825–1899), the wife of James H. Masten who served as postmaster of Cohoes and publisher of the Cohoes Cataract newspaper

- Ann (1828–1915), a career educator who taught school in New York and worked in South Carolina in the years immediately before and after the Civil War.

- Malvina (1832–1920), the wife of Henry J. Haynesworth who was an official of the Confederate government and a merchant in Albany, New York before being appointed as a captain and assistant quartermaster in the U.S. Army during Arthur's presidency

- William (1834–1915), a medical school graduate who became a career Army officer and paymaster, he was wounded during his Civil War service. William Arthur retired in 1898 with the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel, and permanent rank of major.

- George (1836–1838)

- Mary (1841–1917), the wife of John E. McElroy, an Albany businessman and insurance executive, and Arthur's official White House hostess during his presidency

Career

After completing his college preparation at the Lyceum of Union Village (now Greenwich) and a grammar school in Schenectady, Arthur enrolled at Union College there in 1845, where he studied the traditional classical curriculum. In 1848, he became a full-time teacher, and soon began to pursue an education in law. While studying law, he continued teaching. In 1853, after studying at State and National Law School in Ballston Spa, New York, and then saving enough money to relocate, Arthur moved to New York City to read law at the office of Erastus D. Culver, an abolitionist lawyer and family friend. When Arthur was admitted to the New York bar in 1854, he joined Culver's firm, which was subsequently renamed Culver, Parker, and Arthur.

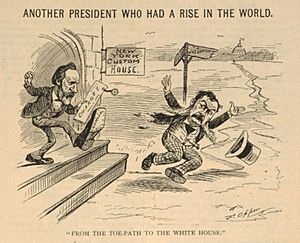

Chester practiced law in New York City. He served as quartermaster general of the New York Militia during the American Civil War. Following the war, he devoted more time to New York Republican politics and quickly rose in Senator Roscoe Conkling's political organization. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him to the post of Collector of the Port of New York in 1871, and he was an important supporter of Conkling and the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. In 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes fired Arthur as part of a plan to reform the federal patronage system in New York.

Vice president

When U.S Representative James Garfield won the Republican nomination for president in 1880, Arthur was nominated for vice president to balance the successful ticket as an Eastern Stalwart. Four months into his term, an assassin shot Garfield, who died 11 weeks later. Arthur then assumed the presidency.

President

At the outset, Arthur struggled to overcome a negative reputation as a Stalwart and product of Conkling's organization. To the surprise of reformers, he advocated and enforced the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

He presided over the rebirth of the US Navy, but he was criticized for failing to alleviate the federal budget surplus which had been accumulating since the end of the Civil War.

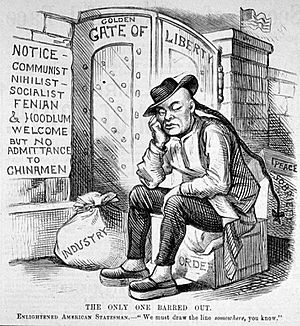

Arthur vetoed the first version of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, arguing that its twenty-year ban on Chinese immigrants to the United States violated the Burlingame Treaty, but he signed a second version, which included a ten-year ban.

Suffering from poor health, Arthur made only a limited effort to secure the Republican Party's nomination in 1884, and he retired at the end of his term.

Modern historians generally rank Arthur as a mediocre president, as well as the least memorable.

Civil service reform

Garfield's assassination by a deranged office seeker amplified the public demand for civil service reform. Both Democratic and Republican leaders realized that they could attract the votes of reformers by turning against the spoils system and, by 1882, a bipartisan effort began in favor of reform. In 1880, Democratic Senator George H. Pendleton of Ohio introduced legislation that required selection of civil servants based on merit as determined by an examination. This legislation greatly expanded similar civil service reforms attempted by President Franklin Pierce 30 years earlier. In his first annual presidential address to Congress in 1881, Arthur requested civil service reform legislation and Pendleton again introduced his bill. Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act into law on January 16, 1883.

Arthur quickly appointed the members of the Civil Service Commission that the law created, and the commission issued its first rules in May 1883; by 1884, half of all postal officials and three-quarters of the Customs Service jobs were to be awarded by merit. That year, Arthur expressed satisfaction with the new system, praising its effectiveness.

Surplus and the tariff

With high revenue held over from wartime taxes, the federal government had collected more than it spent since 1866; by 1882 the surplus reached $145 million. Opinions varied on how to balance the budget; the Democrats wished to lower tariffs, in order to reduce revenues and the cost of imported goods, while Republicans believed that high tariffs ensured high wages in manufacturing and mining. They preferred the government spend more on internal improvements and reduce excise taxes. Arthur agreed with his party, and in 1882 called for the abolition of excise taxes on everything except liquor, as well as a simplification of the complex tariff structure. In May of that year, Representative William D. Kelley of Pennsylvania introduced a bill to establish a tariff commission; the bill passed and Arthur signed it into law but appointed mostly protectionists to the committee. Republicans were pleased with the committee's make-up but were surprised when, in December 1882, they submitted a report to Congress calling for tariff cuts averaging between 20 and 25%. The commission's recommendations were ignored, however, as the House Ways and Means Committee, dominated by protectionists, provided a 10% reduction. After conference with the Senate, the bill that emerged only reduced tariffs by an average of 1.47%. The bill passed both houses narrowly on March 3, 1883, the last full day of the 47th Congress; Arthur signed the measure into law, with no effect on the surplus.

Congress attempted to balance the budget from the other side of the ledger, with increased spending on the 1882 Rivers and Harbors Act in the unprecedented amount of $19 million. While Arthur was not opposed to internal improvements, the scale of the bill disturbed him, as did its narrow focus on "particular localities," rather than projects that benefited a larger part of the nation. On August 1, 1882, Arthur vetoed the bill to widespread popular acclaim; in his veto message, his principal objection was that it appropriated funds for purposes "not for the common defense or general welfare, and which do not promote commerce among the States." Congress overrode his veto the next day and the new law reduced the surplus by $19 million.

Foreign affairs and immigration

Arthur encouraged trade among the nations of the Western Hemisphere; a treaty with Mexico providing for reciprocal tariff reductions was signed in 1882 and approved by the Senate in 1884.

The 47th Congress spent a great deal of time on immigration, and at times was in accord with Arthur. In July 1882 Congress easily passed a bill regulating steamships that carried immigrants to the United States. To their surprise, Arthur vetoed it and requested revisions, which they made and Arthur then approved. He also signed in August of that year the Immigration Act of 1882, which levied a 50-cent tax on immigrants to the United States, and excluded from entry the mentally ill, the intellectually disabled, criminals, or any other person potentially dependent upon public assistance.

A more contentious debate materialized over the status of Chinese immigrants; in January 1868, the Senate had ratified the Burlingame Treaty with China, allowing an unrestricted flow of Chinese into the country. As the economy soured after the Panic of 1873, Chinese immigrants were blamed for depressing workmen's wages; in reaction Congress in 1879 attempted to abrogate the 1868 treaty by passing the Chinese Exclusion Act, but President Hayes vetoed it. Congress was unable to override the veto, but passed a new bill reducing the immigration ban to ten years. Although he still objected to this denial of entry to Chinese laborers, Arthur acceded to the compromise measure, signing the Chinese Exclusion Act into law on May 6, 1882. The Chinese Exclusion Act attempted to stop all Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years, with exceptions for diplomats, teachers, students, merchants, and travelers. It was widely evaded.

In his 1881 annual message, Arthur advocated a stronger Navy. He gave full authority to his new Secretary of Navy William E. Chandler, Hunt's successor. Chandler, an aggressive administrator, purged the Navy of wood-and-canvas warship supporters and created the Naval War College.

Chandler appointed an advisory board to prepare a report on modernization, whose goal was to create a Navy that would protect America thousands of miles away, rather than just coastal waters. Based on the suggestions in the report, Congress appropriated funds, signed into law by Arthur, for the construction of three steel protected cruisers (Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago) and an armed dispatch-steamer (Dolphin), collectively known as the ABCD Ships or the Squadron of Evolution.

Greely polar expedition rescue (1884)

- Further information: Lady Franklin Bay Expedition

By 1883, the ill-fated crew of the U.S. Army 1881 Greely scientific polar expedition was stranded at Fort Conger on Lady Franklin Bay. On July 7, 1881, the Greely crew had left New Foundland, headed northward on the private whaling ship the Proteus. In August 1881, the crew arrived at Lady Franklin Bay without incident or blockage from ice flows. However, after the Proteus dropped off the men and ample provisions, the ship immediately departed and left the expedition to fend for themselves. The men built Fort Conger as a place of refuge and scientific study. Two U.S. supply efforts, in 1882 and 1883, to reach the Greely party, ended in dismal failure. The first, on July 8, 1882, led by William Beebe, on the private steamship Neptune, left St. John's, but was trapped by ice and forced to turn around. On June 29, 1883, the second left St. John's, with two ships, the Proteus, commanded by First Lieutenant Ernest Garlington, U.S. 7th Calvary, and the steam gunboat USS Yantic. The Proteus was crushed by an ice pack, whose stranded crew was rescued by the USS Yantic. Afterward, Garlington abandoned the mission to save Greely and the crew at Fort Conger.

On September 1, 1883, with no relief in sight, Greely and his party left the safety of Fort Conger on small boats, over rough ice-capped waters, and made a permanent base, Camp Clay, at Cape Sabine, on Pim Island, off the eastern shores of the Johan Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, where rations had been placed by the British a few years earlier. However, an attempt by two of Greely's men failed to retrieve the vital food cache over a long distance. Without food or game, the men began to slowly starve to death. On December 17, 1883, President Arthur established a joint Army-Navy commission to make recommendations to Secretary of War Lincoln and Secretary of Navy Chandler on how to rescue the Greely party. Secretary Lincoln actively cooperated with Secretary Chandler in organizing the Greely rescue expedition. Chandler was determined to accomplish a successful rescue of Greely and to restore the honor of the U.S. Navy. Chandler assigned Commander Winfield Schley to command the 1884 Greely Relief Mission. Chandler spared no expense in the rescue effort and had purchased one of the finest sealers afloat, the USS Bear, from Scottish owner Walter Grieve, for $100,000. This was done without authorization, prior to Arthur signing into law the much delayed Greely relief bill.

Chandler vigorously demanded that all of his subordinates in the Naval Department be committed to the relief of the Greely expedition and he drew support from Navy officers. On July 17, 1884, after rescuing the Greely party, Schey arrived at Saint John's, New Foundland and telegraphed to Chandler that the rescue operation was successful. Of the seven rescued, Joseph Elison died on July 8 following multiple amputations. In his fourth annual address to the nation Arthur devoted two paragraphs to the Greely rescue and concluded that "[The] organization and conduct of this relief expedition reflects great credit upon all who contributed to its success."

Civil rights

Since the end of Reconstruction, conservative white Democrats (or "Bourbon Democrats") had regained power in the South, and the Republican party dwindled rapidly as their primary supporters in the region, blacks, were disenfranchised. One crack in the solidly Democratic South emerged with the growth of a new party, the Readjusters, in Virginia. Having won an election in that state on a platform of more education funding (for black and white schools alike) and abolition of the poll tax and the whipping post, many northern Republicans saw the Readjusters as a more viable ally in the South than the moribund southern Republican party. Arthur agreed, and directed the federal patronage in Virginia through the Readjusters rather than the Republicans. He followed the same pattern in other Southern states, forging coalitions with independents and Greenback Party members. Some black Republicans felt betrayed by the pragmatic gambit, but others (including Frederick Douglass and ex-Senator Blanche K. Bruce) endorsed the administration's actions, as the Southern independents had more liberal racial policies than the Democrats. Arthur's coalition policy was only successful in Virginia, however, and by 1885 the Readjuster movement began to collapse with the election of a Democratic president.

In 1882, Arthur signed the Edmunds Act into law; the legislation made polygamy a federal crime, barring polygamists both from public office and the right to vote.

Native American policy

The Arthur administration was challenged by changing relations with western Native American tribes. The American Indian Wars were winding down, and public sentiment was shifting toward more favorable treatment of Native Americans. Arthur urged Congress to increase funding for Native American education, which it did in 1884, although not to the extent he wished. He also favored a move to the allotment system, under which individual Native Americans, rather than tribes, would own land. Arthur was unable to convince Congress to adopt the idea during his administration but, in 1887, the Dawes Act changed the law to favor such a system. The allotment system was favored by liberal reformers at the time, but eventually proved detrimental to Native Americans as most of their land was resold at low prices to white speculators. During Arthur's presidency, settlers and cattle ranchers continued to encroach on Native American territory. Arthur initially resisted their efforts, but after Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller, an opponent of allotment, assured him that the lands were not protected, Arthur opened up the Crow Creek Reservation in the Dakota Territory to settlers by executive order in 1885. Arthur's successor, Grover Cleveland, finding that title belonged to the Native Americans, revoked Arthur's order a few months later.

Personal life

In 1856, Arthur courted Ellen Herndon, the daughter of William Lewis Herndon, a Virginia naval officer. The two were soon engaged to be married. In 1859, they were married at Calvary Episcopal Church in Manhattan. The couple had three children:

- William Lewis Arthur (December 10, 1860 – July 7, 1863), died of "convulsions"

- Chester Alan Arthur II (July 25, 1864 – July 18, 1937), married Myra Townsend, then Rowena Graves, father of Gavin Arthur

- Ellen Hansbrough Herndon "Nell" Arthur Pinkerton (November 21, 1871 – September 6, 1915), married Charles Pinkerton

Images for kids

-

Arthur's home where he spent most of his adulthood years in Manhattan, New York City

-

The New York Custom House (formerly the Merchants' Exchange building at 55 Wall Street) was Arthur's office for seven years.

-

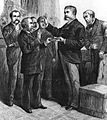

Arthur taking the oath of office as administered by Judge John R. Brady at Arthur's home in New York City, September 20, 1881

-

Chester A. Arthur statue at Madison Square in New York City, Bissell 1898

See also

In Spanish: Chester A. Arthur para niños

In Spanish: Chester A. Arthur para niños