Infantry in the American Civil War facts for kids

The infantry in the American Civil War comprised foot-soldiers who fought primarily with small arms, and carried the brunt of the fighting on battlefields across the United States. Historians have long debated whether the evolution of tactics between 1861 and 1865 marked a seminal point in the evolution of warfare. The conventional narrative is that generals and other officers adhered stubbornly to the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, in which armies employed linear formations and favored open fields over the usage of cover (whether constructed or natural in origin). Presumably, the greater accuracy and range of the rifle musket rendered that approach obsolete, and the Civil War armies' transition to longer battles in 1864 is taken by numerous scholars as proof of the new technology's transformative impact. More recently, however, academics have begun to reject this narrative. Earl J. Hess judges the tactical training of the Civil War as critical to the armies' success, and maintains that the dearth of overwhelming victories during the conflict was actually consistent with the infrequency of such battles throughout history. Allen C. Guelzo contends that rifle muskets did not revolutionize land warfare due to a combination of inadequate firearms training and the poor visibility caused by black powder. This debate has implications not only for the nature of the soldier's experience, but also for the broader question of the Civil War's relative modernity. Williamson Murray and Wayne Wei-Siang Hsieh argue that the conflict was resulted from "the combination...of the Industrial Revolution and French Revolution [which] allowed the opposing sides to mobilize immense numbers of soldiers while projecting military power over great distances." The War involved a number of other recently introduced and new technologies, including military balloons, repeating rifles, the telegraph, and railroads.

Contents

Outbreak of war

At the start of the war, the entire United States Army consisted of 16,367 men of all branches, with infantry representing the vast majority of this total. Some of these infantrymen had seen considerable combat experience in the Mexican–American War, as well as in the West in various encounters, including the Utah War and several campaigns against Indians. However, the majority spent their time on garrison or fatigue duty. In general, the majority of the infantry officers were graduates of military schools such as the United States Military Academy.

In some cases, individual states, such as New York, had previously organized formal militia infantry regiments, originally to fight Indians in many cases, but by 1861, they existed mostly for social camaraderie and parades. These organizations were more prevalent in the South, where hundreds of small local militia companies existed to protect against slave insurrections.

With the secession of eleven Southern states by early 1861 following the election of President Abraham Lincoln, tens of thousands of Southern men flocked to hastily organized companies, which were soon formed into regiments, brigades, and small armies, forming the genesis of the Confederate States Army. Lincoln responded by issuing a call for 75,000 volunteers, and later even more, to put down the rebellion, and the Northern states responded. The resulting forces came to be known as the Volunteer Army (even though they were paid), versus the Regular Army. More than seventeen hundred state volunteer regiments were raised for the Union Army throughout the war, with infantry comprising over 80% of the manpower in these forces.

Organization

The typical infantry regiment of the early Civil War consisted of 10 companies (each with exactly 100 men, according to Hardee's 1855 manual, and led by a captain, with associated lieutenants). Field officers normally included a colonel (commanding), lieutenant colonel, and at least one major. With attrition from disease, battle casualties, desertions and transfers, by the mid-war, most regiments averaged 300–400 men. Volunteer regiments were paid by the individual states, and officers at first were normally elected by popular vote, or were appointed by the state governors (particularly the colonels, who were often the men who had raised and organized the regiment). As the war progressed, the War Department and superior officers began selecting regimental leaders, and the regimental officers normally selected the NCOs (non-commissioned officers) based on performance and merit, although the individual states retained considerable influence in the selection of the regimental officers.

Often, and always, according to Hardee's 1855 manual, large regiments were broken into two or more battalions, with the lieutenant colonel and major(s) in charge of each battalion. The regiment may have also been divided into two wings, the left and right, for instructional purposes, only. The regimental commander exercised overall tactical control over these officers and usually relied on couriers and staff to deliver and receive messages and orders. Normally positioned in the center of the regiment in battle formation was the color guard, typically five to eight men assigned to carry and protect the regimental and/or national colors, led by a color sergeant. Most Union regiments carried both banners; the typical Confederate regiment simply had a national standard.

Individual regiments (usually three to five, although the number varied) were organized and grouped into a larger body (a brigade) which soon became the main structure for battlefield maneuvers. Generally, the brigade was commanded by a brigadier general, or senior colonel, when merit was clearly evident in that colonel and a general was not available. Two to four brigades typically comprised a division, which in theory was commanded by a major general, but theory was often not put into practical application, especially when an officer exhibited exceptional merit or the division was smaller and trusted to a more junior officer. Several divisions would constitute a corps, and multiple corps together made up an army, often commanded by a lieutenant general or full general in the Confederate forces, and by a major general in the Union forces.

Below is charted the average make-up of the infantry for both sides.

Confederate Army

| unit type | low | high | average | most frequent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| corps per army | 1 | 4 | 2.74 | 2 |

| divisions per corps | 2 | 7 | 3.10 | 3 |

| brigades per division | 2 | 7 | 3.62 | 4 |

| regiments per brigade | 2 | 20 | 4.71 | 5 |

Union Army

| unit type | low | high | average | most frequent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| corps per army | 1 | 8 | 3.71 | 3 |

| divisions per corps | 2 | 6 | 2.91 | 3 |

| brigades per division | 2 | 5 | 2.80 | 3 |

| regiments per brigade | 2 | 12 | 4.73 | 4 |

Tactics

Both the Union and Confederate armies utilized a modified form of the linear tactics which defined the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. These tactics had been developed around the use of the smoothbore musket, an inherently inaccurate weapon which (when combined with poor training and the general excitability of battle) was only effective at ranges of forty to sixty yards. For this reason emphasis was placed on volley fire to inflict damage on the enemy. These tactics were transmitted to American commanders in the form of manuals, the three principal ones being Winfield Scott's Infantry Tactics, or Rules for Manoeuvers of the United States Infantry (published in 1835), William J. Hardee's Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics: for the Instruction, Exercise and Maneuver of Riflemen and Light Infantry (1855), and Silas Casey's Infantry Tactics (1862). Other popular instruction manuals included McClellan's Bayonet Drill (1862).

However the Civil War saw the widespread usage of rifled muskets which, utilizing the Minié ball, were capable of accurately hitting targets at ranges of up to 500 yards. This led contemporaries to predict the defender having a distinct advantage over the attacker and higher casualties in battle. After the war, many veterans complained of an inappropriate devotion to Napoleonic tactics, conducting frontal assaults in tightly-packed formations and the casualties it would inevitably cause. Such criticisms were picked up by later historians such as Edward Hagerman, writing that the rifled musket doomed the frontal assault and led to the introduction of trench warfare.

More recently, historians have questioned this narrative and found that (despite the rifled musket's superiority) infantry combat most often took place at ranges similar to those of smoothbore muskets and the causality rates were little different than from earlier wars. A number of factors are said to explain this seeming contradiction between technology and tactical reality. Allen Guelzo points out two technological limitations which reduced the rifled musket's effective range, the first being its continued use of black powder. The billowing clouds of smoke created from firing these weapons could become so thick as to reduce visibility to "less than fifty paces" and prevent accuracy at range. The second is that the unique ballistic properties of the Minié ball meant that it followed a curved trajectory which required a well-trained shooter to utilize it at range.

These were compounded by the fact that target practice was for all intents and purposes nonexistent in both armies of the Civil War. While officers were encouraged to give their men this training, no funds were actually provided to carry them out. The result of this deficiency was readily apparent. In one instance, forty men from the 5th Connecticut fired on a fifteen-foot high barn from a distance of one hundred yards: just four actually hit the barn, and only one at a height that would have hit a man. In another, a soldier of the 1st South Carolina remarked that the chief casualties from an intense firefight conducted at one hundred yards were the needles and pinecones from the trees above them. Highly-trained sharpshooters could utilize rifled muskets to their full potential but for most infantry a lack of training combined with the natural stresses of battle meant that the best one could do was "simply raise his rifle to the horizontal, and fire without aiming." Likewise, Paddy Griffith also found no evidence that the elaborate earthworks of the Civil War were any more necessary to deal with modern rifle weaponry than they had been in previous wars. Instead he argues their increasing prevalence during the war was due to psychological reasons: a more risk-adverse populace combined with officers influenced by the defensive-oriented teachings of men like Dennis Hart Mahan.

Historian Earl J. Hess argues that, given all these factors, the continued use of linear tactics by infantry in the Civil War were appropriate, and the most successful units were those most familiar with these tactics. An increase in volume of fire rather than range may have necessitate a change in tactics, but the breechloader and repeating firearms which promised to do so were simply not available in sufficient quantities until well after the war.

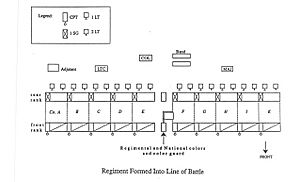

The core of these tactics was organizing soldiers into ranks and files in order to form a regiment into a line of battle or column. The line was the primary formation of combat as it allowed the soldiers to fire a full volley at the enemy. Generally consisting of companies formed up into two ranks with files close enough to touch elbows, the line was held in alignment by placing the regimental colors in the center and a designated guide on either end of the line. File closers spread out just behind the line helped ensure order and prevented soldiers from deserting. Thus organized, a standard 475-man regiment occupied a front of 140 yards. The column was primarily used for maneuvering, with a simple column consisting of companies stacked up behind one another at varying distances. More common was the double column consisting of two stacks of companies next to each other as doing so shortened the formation's length and widened its frontage. Infantry squares were rarely employed, both because they were the most difficult formation to carry out and because they were rarely necessary on Civil War battlefields.

Of particular tactical importance was the usage of skirmishers, which Hess argues reached its apogee during the Civil War. The textbook deployment of skirmishers was for a company to break into platoons, one of which formed the skirmish line and the other as a reserve 150 paces behind it. Soldiers deployed as skirmishers operated in groups of four known as "comrades in battle" spaced out at five-pace intervals, with spacing of twenty to forty paces between each group. Standard practice was for two companies to form a skirmish line for a regiment, while on a larger scale a regiment would form a skirmish line for a brigade. In essence a more advanced form of the line of battle, skirmish lines nevertheless required greater individual skill and determination of the soldiers forming it. They could act as a screen for a defensive line from oncoming enemy soldiers, harassing attackers as they approached, or probed an enemy's strength in preparation for an attack and screen the assaulting force. Some regiments were more adept at skirmishing than others, but most were adequate in the role.

The most common means by which an infantry attack was carried out was with multiple or successive waves of battle lines approaching the enemy. Rather than having each line be formed of regiments under one commander, the proper way was to assign sectors of the battlefield to a commander so they could form successive lines with their own regiments, thereby allowing greater command and control. Successive lines were best spaced out a couple hundred yards from each other so that they were far enough away to avoid being hit by the same fire yet close enough to provide support. The use of successive lines also necessitated an understanding how to pass one line through another, as doing so carelessly easily caused confusion. It was also common for successive lines to be organized into an echelon formation to protect an exposed flank or outflank an opposing line.

Weapons and equipment

Trained in the era of short-range smoothbore muskets, such as the Springfield Model 1842, which was issued to many units immediately prior to the war, many generals often did not fully appreciate or understand the importance and power of the new weapons introduced during the war, such as the 1861 Springfield rifled musket and comparable rifles which had longer range and were more powerful than the weapons used by the antebellum armies. Its barrel contained several rifled grooves that provided increased accuracy, and fired a .58 caliber Minié ball (a small conical-shaped ball). This rifle had a deadly effect up to 600 yards and was capable of seriously wounding a man beyond 1,000 yards, unlike the previous muskets used during the American Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars, most of which had an effective range of only 100 yards.

However, as stated above, historians like Guelzo argue these benefits were largely nullified by the lack of visibility on a Civil War battlefield. Engagements necessarily took place with massed lines of infantry at ranges of around 100 yards, for the simple fact the enemy could not be seen at longer distances since neither side employed smokeless powder in their weapons. In many engagements, unless there was a strong wind on the battlefield, the first volley from each side would obscure the enemy's line for a considerable time in gunsmoke. Hence, the standard doctrine on both sides was to close with the enemy and fire at point-blank range for maximum effect.

Even smoothbore muskets underwent improvements: soldiers developed the technique of "buck and ball," loading the muskets with a combination of small pellets and a single round ball, effectively making their fire scattergun-like in effect. Other infantrymen went into combat armed with shotguns, pistols, knives, and assorted other killing instruments. Very early in the war, a few companies were armed with pikes. However, by the end of 1862, most infantrymen were armed with rifles, including imports from Great Britain, Belgium, and other European countries.

The typical Union soldier carried his musket, percussion cap box, cartridge box, a canteen, a knapsack, and other accoutrements, in addition to any personal effects. By contrast, many Southern soldiers carried their possessions in a blanket roll worn around the shoulder and tied at the waist. They might have a wooden canteen, a linen or cotton haversack for food, and a knife or similar sidearm, as well as their musket.

One primary account of the typical infantryman came from James Gall, a representative of the United States Sanitary Commission, who observed Confederate infantrymen of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in camp in the occupied borough of York, Pennsylvania, in late June 1863, sometime after the Second Battle of Winchester.

Physically, the men looked about equal to the generality of our own troops, and there were fewer boys among them. Their dress was a wretched mixture of all cuts and colors. There was not the slightest attempt at uniformity in this respect. Every man seemed to have put on whatever he could get hold of, without regard to shape or color. I noticed a pretty large sprinkling of blue pants among them, some of those, doubtless, that were left by Milroy at Winchester. Their shoes, as a general thing, were poor; some of the men were entirely barefooted. Their equipments were light, as compared with those of our men. They consisted of a thin woolen blanket, coiled up and slung from the shoulder in the form of a sash, a haversack swung from the opposite shoulder, and a cartridge-box. The whole cannot weigh more than twelve or fourteen pounds. Is it strange, then, that with such light loads, they should be able to make longer and more rapid marches than our men? The marching of the men was irregular and careless, their arms were rusty and ill kept. Their whole appearance was greatly inferior to that of our soldiers... There were not tents for the men, and but few for the officers... Everything that will trammel or impede the movement of the army is discarded, no matter what the consequences may be to the men... In speaking of our soldiers, the same officer remarked: 'They are too well fed, too well clothed, and have far too much to carry.' That our men are too well fed, I do not believe, neither that they are too well clothed; that they have too much to carry, I can very well believe, after witnessing the march of the Army of the Potomac to Chancellorsville. Each man had eight days' rations to carry, besides sixty rounds of ammunition, musket, woollen blanket, rubber blanket, overcoat, extra shirt, drawers, socks, and shelter tent, amounting in all to about sixty pounds. Think of men, and boys too, staggering along under such a load, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day.

Rapid-fire weapons

While thousands of repeating rifles and breechloaders, such as the 7-shot Spencer and 15-shot Henry models, were fielded to Union cavalry in the war, no significant funds were allocated to furnish Union infantry with the same equipment. With the exception of some volunteer regiments receiving extra funding from their state or wealthy commander, the small numbers of rapid-fire weapons in service with US infantrymen, often skirmishers, were mostly purchased privately by soldiers themselves.

Despite President Lincoln's enthusiasm for these types of weapons, the mass adoption of repeating rifles for the infantry was resisted by some senior Union officers. The most common concerns cited about the weapons were their high-cost, massive use of ammunition and the considerable extra smoke produced on the battlefield. The most influential detractor of these new rifles was 67-year-old General James Ripley, the US Army's ordnance chief. He adamantly opposed the adoption of, what he called, "these newfangled gimcracks," believing they would encourage soldiers to "waste ammunition." He also argued that the quartermaster corps could not field enough ammunition to keep a repeater-armed army supplied for any extended campaign.

One notable exception was Colonel John T. Wilder's mounted infantry "Lightning Brigade." Col. Wilder, a wealthy engineer and foundry owner, took out a bank loan to purchase 1,400 Spencer rifles for his infantrymen. The magazine-fed weapons were quite popular with his soldiers, with most agreeing to monthly pay deductions to help reimburse the costs. During the Battle of Hoover's Gap, Wilder's Spencer-armed and well-fortified brigade of 4,000 men held off 22,000 attacking Confederates, and inflicted 287 casualties for only 27 losses. Even more striking, during the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, his Spencer-armed brigade launched a counterattack against a much larger Confederate division overrunning the Union's right flank. Thanks in large part to the Lightning Brigade's superior firepower, they repulsed the Confederates and inflicted over 500 casualties, while suffering only 53 losses.