Henrietta Swan Leavitt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henrietta Swan Leavitt

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 4, 1868 Lancaster, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | December 12, 1921 (aged 53) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Radcliffe College, Oberlin College |

| Known for | Leavitt's law: the period-luminosity relationship for Cepheid variables |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | Harvard University |

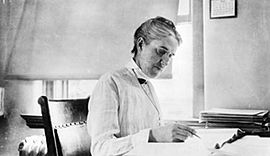

Henrietta Swan Leavitt ( July 4, 1868 – December 12, 1921) was an American astronomer. A graduate of Radcliffe College, she worked at the Harvard College Observatory as a "computer", tasked with examining photographic plates in order to measure and catalog the brightness of stars. This work led her to discover the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variables. Leavitt's discovery provided astronomers with the first "standard candle" with which to measure the distance to faraway galaxies.

Before Leavitt discovered the period-luminosity relationship for Cepheid variables, the only techniques available to astronomers for measuring the distance to a star were based on parallax and triangulation. Such techniques can only be used for measuring distances up to hundreds of light years. Leavitt's work allowed astronomers to measure distances up to about 20 million light years. As a result of this, it is now known that our own galaxy, the Milky Way, has a diameter of about 100,000 light years. After Leavitt's death, Edwin Hubble used Leavitt's period-luminosity relation, together with the galactic spectral shifts first measured by Vesto Slipher at Lowell Observatory, to establish that the universe is expanding (see Hubble's law).

Contents

Biography

Early years and education

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, the daughter of Congregational church minister George Roswell Leavitt and his wife Henrietta Swan Kendrick. She was a descendant of Deacon John Leavitt, an English Puritan tailor, who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 17th century. (In the early Massachusetts records the family name was spelled "Levett".) Henrietta Leavitt remained deeply religious and committed to her church throughout her life.

Leavitt attended Oberlin College before transferring to Harvard University's Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women (later Radcliffe College), receiving a bachelor's degree in 1892. At Oberlin and Harvard, Leavitt studied a broad curriculum that included Latin and classical Greek, fine arts, philosophy, analytic geometry, and calculus. It wasn't until her fourth year of college that Leavitt took a course in astronomy, in which she earned an A–. Leavitt also began working as one of the women "computers" at the Harvard College Observatory, hired by its director Edward Charles Pickering to measure and catalog the brightness of stars as they appeared in the observatory's photographic plate collection. (In the early 1900s, women were not allowed to operate telescopes.)

In 1893, Leavitt obtained credits toward a graduate degree in astronomy for her work at the Harvard College Observatory, but she never completed that degree. In 1898 she became a member of the Harvard staff, as their first "Curator of Astronomical Photographs" dubious. Leavitt left the observatory to make two trips to Europe and completed a stint as an art assistant at Beloit College in Wisconsin. At this time, she contracted an illness that led to progressive hearing loss.

Astronomical career

Leavitt returned to the Harvard College Observatory from her travels in 1903. Because Leavitt had independent means, Pickering initially did not have to pay her. Later, she received $0.30 (equivalent to $9.77 in 2022), an hour for her work, being paid only $10.50 (equivalent to $341.99 in 2022) per week. She was reportedly "hard-working, serious-minded …, little given to frivolous pursuits and selflessly devoted to her family, her church, and her career". One of the women that Leavitt worked with at the Harvard Observatory was Annie Jump Cannon, who shared the experience of being deaf.

Pickering assigned Leavitt to the study of variable stars of the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds, as recorded on photographic plates taken with the Bruce Astrograph of the Boyden Station of the Harvard Observatory in Arequipa, Peru. She identified 1,777 variable stars. In 1908 she published her results in the Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, noting that the brighter variables had the longer period.

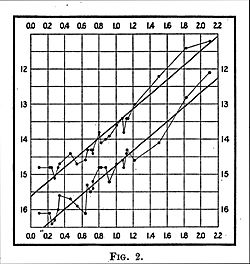

In another paper published in 1912, Leavitt looked carefully at the relationship between the periods and the brightness of a sample of 25 of the Cepheids variables in the Small Magellanic Cloud. This paper was communicated and signed by Edward Pickering, but the first sentence indicates that it was "prepared by Miss Leavitt". Leavitt made a graph of magnitude versus logarithm of period and determined that, in her own words,

A straight line can be readily drawn among each of the two series of points corresponding to maxima and minima, thus showing that there is a simple relation between the brightness of the Cepheid variables and their periods.

She then used the simplifying assumption that all of the Cepheids within the Small Magellanic Cloud were at approximately the same distance, so that their intrinsic brightness could be deduced from their apparent brightness as registered in the photographic plates, up to a scale factor since the distance to the Magellanic Clouds were as yet unknown. She expressed the hope that parallaxes to some Cepheids would be measured, which soon happened, thereby allowing her period-luminosity scale to be calibrated. This reasoning allowed Leavitt to establish that the logarithm of the period is linearly related to the logarithm of the star's average intrinsic optical luminosity (which is the amount of power radiated by the star in the visible spectrum).

Leavitt also developed, and continued to refine, the Harvard Standard for photographic measurements, a logarithmic scale that orders stars by brightness over 17 magnitudes. She initially analyzed 299 plates from 13 telescopes to construct her scale, which was accepted by the International Committee of Photographic Magnitudes in 1913.

In 1913, Leavitt discovered T Pyxidis, a recurrent nova in Pyxis, and one of the most frequent recurrent novae in the sky with eruptions observed in 1890, 1902, 1920, 1944, 1967, and 2011.

Leavitt was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the American Association of University Women, the American Astronomical and Astrophysical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and an honorary member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. In 1921, when Harlow Shapley took over as director of the observatory, Leavitt was made head of stellar photometry. By the end of that year she had succumbed to cancer and was buried in the Leavitt family plot at Cambridge Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Scientific impact

According to science writer Jeremy Bernstein, "variable stars had been of interest for years, but when she was studying those plates, I doubt Pickering thought she would make a significant discovery—one that would eventually change astronomy." The period–luminosity relationship for Cepheids, now known as "Leavitt's law", made the stars the first "standard candle" in astronomy, allowing scientists to compute the distances to stars too remote for stellar parallax observations to be useful. One year after Leavitt reported her results, Ejnar Hertzsprung determined the distance of several Cepheids in the Milky Way and that, with this calibration, the distance to any Cepheid could be accurately determined.

Cepheids were soon detected in other galaxies, such as Andromeda (notably by Edwin Hubble in 1923–24), and they became an important part of the evidence that "spiral nebulae" are independent galaxies located far outside of our own Milky Way. Thus, Leavitt's discovery would forever change our picture of the universe, as it prompted Harlow Shapley to move our Sun from the center of the galaxy in the "Great Debate" and Edwin Hubble to move our galaxy from the center of the universe.

Leavitt's discovery of a way to accurately measure distances on an inter-galactic scale, paved the way for modern astronomy's understanding of the structure and scale of the universe. The accomplishments of Edwin Hubble, the American astronomer who established that the universe is expanding, also were made possible by Leavitt's groundbreaking research. Hubble often said that Leavitt deserved the Nobel Prize for her work. Mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences, tried to nominate her for that prize in 1925, only to learn that she had died of cancer three years earlier. (The Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.)

Cepheid variables allow astronomers to measure distances up to about 20 million light years. Even greater distances can now be measured by using the theoretical maximum mass of white dwarfs calculated by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar.

Illness and death

Leavitt's scientific work at Harvard was frequently interrupted by illness and family obligations. Her early death at the age of 53 from stomach cancer was seen as a tragedy by her colleagues for reasons that went beyond her scientific achievements. Her colleague Solon I. Bailey wrote in her obituary that "she had the happy, joyful, faculty of appreciating all that was worthy and lovable in others, and was possessed of a nature so full of sunshine that, to her, all of life became beautiful and full of meaning."

"Sitting at the top of a gentle hill," writes George Johnson in his biography of Leavitt, "the spot is marked by a tall hexagonal monument, on top of which sits a globe cradled on a draped marble pedestal. Her uncle Erasmus Darwin Leavitt and his family also are buried there, along with other Leavitts". A plaque memorializing Henrietta and her two siblings, Mira and Roswell, is mounted on one side of the monument. Nearby are the graves of Henry and William James. There is no epitaph at the gravesite memorializing Henrietta Leavitt's achievements in astronomy.

Posthumous honors

- The asteroid 5383 Leavitt and the crater Leavitt on the Moon are named after her to honor deaf men and women who have worked as astronomers.

- One of the ASAS-SN telescopes, located in the McDonald Observatory in Texas, is named in her honor.

Books and plays

Lauren Gunderson wrote a play, Silent Sky, which followed Leavitt's journey from her acceptance at Harvard to her death.

George Johnson wrote a biography, Miss Leavitt's Stars, which showcases the triumphs of women's progress in science through the story of Leavitt.

Robert Burleigh wrote the biography Look Up!: Henrietta Leavitt, Pioneering Woman Astronomer for a younger audience. It is written for four- to eight-year-olds.

Theo Strassell wrote a play, "The Troubling Things We Do," an absurdist piece that details the life of Henrietta Leavitt, among other scientists from her era.

Images for kids

-

The Harvard Computers, a group of women computers at the Harvard College Observatory, who worked for the astronomer Edward Charles Pickering. The group included Annie Jump Cannon, Williamina Fleming, and Antonia Maury.

See also

In Spanish: Henrietta Swan Leavitt para niños

In Spanish: Henrietta Swan Leavitt para niños