Helen of Troy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Helen |

|

|---|---|

| Queen of Sparta Princess of Troy |

|

|

|

| Abode | Sparta (modern-day Sparta, Greece) Troy (modern-day Hisarlik, Turkey) |

| Personal information | |

| Born | Sparta, Greece |

| Died | Sparta, Greece |

| Consort | Menelaus Paris Deiphobus |

| Offspring |

At least 5, including Hermione

by Menelaus

by Paris

|

| Parents | |

| Siblings | Pollux (full-brother) Clytemnestra, Castor, Timandra, Phoebe, Philonoe and other children of Zeus (half-siblings) |

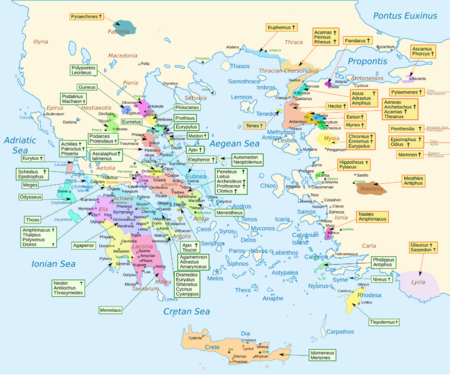

Helen (Ancient Greek: Ἑλένη, romanized: Helénē ), also known as Helen of Troy, Helen of Argos, or Helen of Sparta, and in Latin as Helena, was a figure in Greek mythology said to have been the most beautiful woman in the world. She was believed to have been the daughter of Zeus and Leda or Nemesis, and the sister of Clytemnestra, Castor, Pollux, Philonoe, Phoebe and Timandra. She was married to King Menelaus of Sparta "who became by her the father of Hermione, and, according to others, of Nicostratus also." Her abduction by Paris of Troy was the most immediate cause of the Trojan War.

Elements of her putative biography come from classical authors such as Aristophanes, Cicero, Euripides, and Homer (in both the Iliad and the Odyssey). Her story reappears in Book II of Virgil's Aeneid. In her youth, she was abducted by Theseus. A competition between her suitors for her hand in marriage saw Menelaus emerge victorious. All of her suitors were required to swear an oath (known as the Oath of Tyndareus) promising to provide military assistance to the winning suitor, if Helen were ever stolen from him. The obligations of the oath precipitated the Trojan War. When she married Menelaus she was still very young; whether her subsequent departure with Paris was an abduction or an elopement is ambiguous (probably deliberately so).

The legends of Helen during her time in Troy are contradictory: Homer depicts her ambivalently, both regretful of her choice and sly in her attempts to redeem her public image. In some versions, Helen doesn't arrive in Troy, but instead waits out the war in Egypt. Ultimately, Paris was killed in action, and in Homer's account Helen was reunited with Menelaus, though other versions of the legend recount her ascending to Olympus instead. A cult associated with her developed in Hellenistic Laconia, both at Sparta and elsewhere; at Therapne she shared a shrine with Menelaus. She was also worshiped in Attica and on Rhodes.

Her beauty inspired artists of all times to represent her, frequently as the personification of ideal human beauty. Images of Helen start appearing in the 7th century BC. In classical Greece, her abduction by Paris—or escape with him—was a popular motif.

Contents

Etymology

The etymology of Helen's name continues to be a problem for scholars. In the 19th century, Georg Curtius related Helen (Ἑλένη) to the moon (Selene; Σελήνη). But two early dedications to Helen in the Laconian dialect of ancient Greek spell her name with an initial digamma (Ϝ, probably pronounced like a w), which rules out any etymology originally starting with simple *s-.

In the early 20th century, Émile Boisacq considered Ἑλένη to derive from the well-known noun ἑλένη meaning "torch". It has also been suggested that the λ of Ἑλένη arose from an original ν, and thus the etymology of the name would be connected with the root of Venus. Linda Lee Clader, however, says that none of the above suggestions offers much satisfaction.

More recently, Otto Skutsch has advanced the theory that the name Helen might have two separate etymologies, which belong to different mythological figures respectively, namely *Sṷelenā (related to Sanskrit svaraṇā "the shining one") and *Selenā, the first a Spartan goddess, connected to one or the other natural light phenomenon (especially St. Elmo's fire) and sister of the Dioscuri, the other a vegetation goddess worshiped in Therapne as Ἑλένα Δενδρῖτις ("Helena of the Trees").

Others have connected the name's etymology to a hypothetical Proto-Indo-European sun goddess, noting the name's connection to the word for "sun" in various Indo-European cultures including the Greek proper word and god for the sun, Helios. In particular, her marriage myth may be connected to a broader Indo-European "marriage drama" of the sun goddess, and she is related to the divine twins, just as many of these goddesses are. Martin L. West has thus proposed that Helena ("mistress of sunlight") may be constructed on the PIE suffix -nā ("mistress of"), connoting a deity controlling a natural element.

Prehistoric and mythological context

Helen first appears in the poems of Homer, after which she became a popular figure in Greek literature. These works are set in the final years of the Age of Heroes, a mythological era which features prominently in the canon of Greek myth. Because the Homeric poems are known to have been transmitted orally before being written down, some scholars speculate that such stories were passed down from earlier Mycenaean Greek tradition, and that the Age of Heroes may itself reflect a mythologized memory of that era.

Recent archaeological excavations in Greece suggest that modern-day Laconia was a distinct territory in the Late Bronze Age, while the poets narrate that it was a rich kingdom. Archaeologists have unsuccessfully looked for a Mycenaean palatial complex buried beneath present-day Sparta. Modern findings suggest the area around Menelaion in the southern part of the Eurotas valley seems to have been the center of Mycenaean Laconia.

Family

Helen and Menelaus had a daughter, Hermione. Different sources say she was also the mother of one or more sons, named Aethiolas, Nicostratus, Megapenthes and Pleisthenes. Still, according to others, these were instead illegitimate children of Menelaus and various lovers.

Helen and Paris had three sons, Bunomus, Aganus, Idaeus, and a daughter also called Helen. The three sons died during the Trojan War when an earthquake caused the roof of the room where they slept to collapse.

Mythology

Birth

In most sources, including the Iliad and the Odyssey, Helen is the daughter of Zeus and of Leda, the wife of the Spartan king Tyndareus. Euripides' play Helen, written in the late 5th century BC, is the earliest source to report the most familiar account of Helen's birth: that, although her putative father was Tyndareus, she was actually Zeus' daughter.

On the other hand, in the Cypria, part of the Epic Cycle, Helen was the daughter of Zeus and the goddess Nemesis.

Youthful abduction by Theseus

Two Athenians, Theseus and Pirithous, thought that since they were sons of gods, they should have divine wives; they thus pledged to help each other abduct two daughters of Zeus. Theseus chose Helen, and Pirithous vowed to marry Persephone, the wife of Hades. Theseus took Helen and left her with his mother Aethra or his associate Aphidnus at Aphidnae or Athens. Theseus and Pirithous then traveled to the underworld, the domain of Hades, to kidnap Persephone. Hades pretended to offer them hospitality and set a feast, but, as soon as the pair sat down, snakes coiled around their feet and held them there. Helen's abduction caused an invasion of Athens by Castor and Pollux, who captured Aethra in revenge, and returned their sister to Sparta. In Goethe's Faust, Centaur Chiron is said to have aided the Dioscuri brothers in returning Helen home.

In most accounts of this event, Helen was quite young; Hellanicus of Lesbos said she was seven years old and Diodorus makes her ten years old. On the other hand, Stesichorus said that Iphigenia was the daughter of Theseus and Helen, which implies that Helen was of childbearing age. In most sources, Iphigenia is the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, but Duris of Samos and other writers , such as Antoninus Liberalis , followed Stesichorus' account.

Sextus Propertius imagines Helen as a girl who practices arms and hunts with her brothers.

Suitors

When it was time for Helen to marry, many kings and princes from around the world came to seek her hand, bringing rich gifts with them or sent emissaries to do so on their behalf. During the contest, Castor and Pollux had a prominent role in dealing with the suitors, although the final decision was in the hands of Tyndareus. Menelaus, her future husband, did not attend but sent his brother, Agamemnon, to represent him.

Oath of Tyndareus

Tyndareus was afraid to select a husband for his daughter, or send any of the suitors away, for fear of offending them and giving grounds for a quarrel. Odysseus was one of the suitors, but had brought no gifts because he believed he had little chance to win the contest. He thus promised to solve the problem, if Tyndareus in turn would support him in his courting of Penelope, the daughter of Icarius. Tyndareus readily agreed, and Odysseus proposed that, before the decision was made, all the suitors should swear a most solemn oath to defend the chosen husband against whoever should quarrel with him. After the suitors had sworn not to retaliate, Menelaus was chosen to be Helen's husband. As a sign of the importance of the pact, Tyndareus sacrificed a horse. Helen and Menelaus became rulers of Sparta, after Tyndareus and Leda abdicated. Menelaus and Helen rule in Sparta for at least ten years; they have a daughter, Hermione, and (according to some myths) three sons: Aethiolas, Maraphius, and Pleisthenes.

The marriage of Helen and Menelaus marks the beginning of the end of the age of heroes. Concluding the catalog of Helen's suitors, Hesiod reports Zeus' plan to obliterate the race of men and the heroes in particular. The Trojan War, caused by Helen's elopement with Paris, is going to be his means to this end.

In Egypt

At least three Ancient Greek authors denied that Helen ever went to Troy; instead, they suggested, Helen stayed in Egypt during the Trojan War. Those three authors are Euripides, Stesichorus, and Herodotus. In the version put forth by Euripides in his play Helen, Hera fashioned a likeness (eidolon, εἴδωλον) of Helen out of clouds at Zeus' request, Hermes took her to Egypt, and Helen never went to Troy, but instead spent the entire war in Egypt. An eidolon is also present in Stesichorus' account, but not in Herodotus' rationalizing version of the myth. In addition to these accounts, Lycophron (822) states that Hesiod was the first to mention Helen's eidolon. This may mean Hesiod stated this in a literary work, or that the idea was widely known/circulated in early archaic Greece during the time of Hesiod and was consequently attributed to him.

Herodotus adds weight to the "Egyptian" version of events by putting forward his own evidence—he traveled to Egypt and interviewed the priests of the temple (Foreign Aphrodite, ξείνη Ἀφροδίτη) at Memphis. According to these priests, Helen had arrived in Egypt shortly after leaving Sparta, because strong winds had blown Paris's ship off course. King Proteus of Egypt, appalled that Paris had fallen in love with his host's wife and plundered his host's home in Sparta, disallowed Paris from taking Helen to Troy. Paris returned to Troy without a new bride, but the Greeks refused to believe that Helen was in Egypt and not within Troy's walls. Thus, Helen waited in Memphis for ten years, while the Greeks and the Trojans fought. Following the conclusion of the Trojan War, Menelaus sailed to Memphis, where Proteus reunited him with Helen.

In Troy

When he discovered that his wife was missing, Menelaus called upon all the other suitors to fulfill their oaths, thus beginning the Trojan War.

The Greek fleet gathered in Aulis, but the ships could not sail for lack of wind. Artemis was enraged by a sacrilege, and only the sacrifice of Agamemnon's daughter, Iphigenia, could appease her. In Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis, Clytemnestra, Iphigenia's mother and Helen's sister, begs her husband to reconsider his decision, calling Helen a "wicked woman". Clytemnestra tries to warn Agamemnon that sacrificing Iphigenia for Helen's sake is, "buying what we most detest with what we hold most dear".

-

Helen on the Ramparts of Troy was a popular theme in late 19th-century art – seen here a depiction by Frederick Leighton.

-

In a similar fashion to Leighton, Gustave Moreau depicts an expressionless Helen; a blank or anguished face.

-

Lithographic illustration by Walter Crane

Before the opening of hostilities, the Greeks dispatched a delegation to the Trojans under Odysseus and Menelaus; they endeavored without success to persuade Priam to hand Helen back. A popular theme, The Request of Helen (Helenes Apaitesis, Ἑλένης Ἀπαίτησις), was the subject of a drama by Sophocles, now lost.

Homer paints a poignant, lonely picture of Helen in Troy. She is filled with self-loathing and regret for what she has caused; by the end of the war, the Trojans have come to hate her. When Hector dies, she is the third mourner at his funeral, and she says that, of all the Trojans, Hector and Priam alone were always kind to her:

Wherefore I wail alike for thee and for my hapless self with grief at heart;

for no longer have I anyone beside in broad Troy that is gentle to me or kind;

but all men shudder at me.

These bitter words reveal that Helen gradually realized Paris' weaknesses, and decided to ally herself with Hector. There is an affectionate relationship between the two, and Helen has harsh words for Paris when she compares the two brothers:

Howbeit, seeing the gods thus ordained these ills,

would that I had been wife to a better man,

that could feel the indignation of his fellows and their many revilings. [...]

But come now, enter in, and sit thee upon this chair, my brother,

since above all others has trouble encompassed thy heart

because of shameless me, and the folly of Alexander.

After Paris was killed in combat, there was some dispute among the Trojans about which of Priam's surviving sons she should remarry: Helenus or Deiphobus, but she was given to the latter.

During the Fall of Troy

During the fall of Troy, Helen's role is ambiguous. From one side, we read about the treacherous Helen who simulated Bacchic rites and rejoiced over the carnage of Trojans. On the other hand, there is another Helen, lonely and helpless; desperate to find sanctuary, while Troy is on fire. Stesichorus narrates that both Greeks and Trojans gathered to stone her to death. When Menelaus finally found her, he raised his sword to kill her. He had demanded that only he should slay his wife; but, when he was ready to do so, she dropped her robe from her shoulders, and the sight of her beauty caused him to let the sword drop from his hand.

Fate

Helen returned to Sparta and lived with Menelaus, where she was encountered by Telemachus in Book 4 of The Odyssey. As depicted in that account, she and Menelaus were completely reconciled and had a harmonious married life—he holding no grudge at her having run away with a lover and she feeling no restraint in telling anecdotes of her life inside besieged Troy.

According to another version, used by Euripides in his play Orestes, Helen had been saved by Apollo from Orestes and was taken up to Mount Olympus almost immediately after Menelaus' return. A curious fate is recounted by Pausanias the geographer (3.19.11–13), which has Helen share the afterlife with Achilles.

In Euripides's tragedy The Trojan Women, Helen is shunned by the women who survived the war and is to be taken back to Greece to face a death sentence. This version is contradicted by two of Euripides' other tragedies, Electra, which predates The Trojan Women, and Helen, as Helen is described as being in Egypt during the events of the Trojan War in each.

Artistic representations

From Antiquity, depicting Helen would be a remarkable challenge. The story of Zeuxis deals with this exact question: how would an artist immortalize ideal beauty? He eventually selected the best features from five virgins. The ancient world starts to paint Helen's picture or inscribe her form on stone, clay and bronze by the 7th century BC. Dares Phrygius describes Helen in his History of the Fall of Troy: "She was beautiful, ingenuous, and charming. Her legs were the best; her mouth the cutest. There was a beauty-mark between her eyebrows."

Helen is frequently depicted on Athenian vases as being threatened by Menelaus and fleeing from him. This is not the case, however, in Laconic art: on an Archaic stele depicting Helen's recovery after the fall of Troy, Menelaus is armed with a sword but Helen faces him boldly, looking directly into his eyes; and in other works of Peloponnesian art, Helen is shown carrying a wreath, while Menelaus holds his sword aloft vertically. In contrast, on Athenian vases of c. 550–470, Menelaus threateningly points his sword at her.

The abduction by Paris was another popular motif in ancient Greek vase-painting; definitely more popular than the kidnapping by Theseus. In a famous representation by the Athenian vase painter Makron, Helen follows Paris like a bride following a bridegroom, her wrist grasped by Paris' hand. The Etruscans, who had a sophisticated knowledge of Greek mythology, demonstrated a particular interest in the theme of the delivery of Helen's egg, which is depicted in relief mirrors.

In Renaissance painting, Helen's departure from Sparta is usually depicted as a scene of forcible abduction by Paris. This is not, however, the case with certain secular medieval illustrations. Artists of the 1460s and 1470s were influenced by Guido delle Colonne's Historia destructionis Troiae. In the Florentine Picture Chronicle Paris and Helen are shown departing arm in arm, while their marriage was depicted into Franco-Flemish tapestry.

In Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (1604), Faust conjures the shade of Helen. Upon seeing Helen, Faustus speaks the famous line: "Was this the face that launch'd a thousand ships, / And burnt the topless towers of Ilium." (Act V, Scene I.) Helen is also conjured by Faust in Goethe's Faust.

In William Shakespeare's play Troilus and Cressida, Helen is a minor character who adores Troilus.

In Pre-Raphaelite art, Helen is often shown with shining curly hair and ringlets. Other painters of the same period depict Helen on the ramparts of Troy, and focus on her expression: her face is expressionless, blank, inscrutable. In Gustave Moreau's painting, Helen will finally become faceless; a blank eidolon in the middle of Troy's ruins.

Cult

The major centers of Helen's cult were in Laconia. At Sparta, the urban sanctuary of Helen was located near the Platanistas, so called for the plane trees planted there. Ancient sources associate Helen with gymnastic exercises or/and choral dances of maidens near the Evrotas River. This practice is referenced in the closing lines of Lysistrata, where Helen is said to be the "pure and proper" leader of the dancing Spartan women. Theocritus conjures the song epithalamium Spartan women sung at Platanistas commemorating the marriage of Helen and Menelaus:

We first a crown of low-growing lotus

having woven will place it on a shady plane-tree.

First from a silver oil-flask soft oil

drawing we will let it drip beneath the shady plane-tree.

Letters will be carved in the bark, so that someone passing by

may read in Doric: "Reverence me. I am Helen's tree."

Helen's worship was also present on the opposite bank of Eurotas at Therapne, where she shared a shrine with Menelaus and the Dioscuri. The shrine has been known as the Menelaion (the shrine of Menelaus), and it was believed to be the spot where Helen was buried alongside Menelaus. Despite its name, both the shrine and the cult originally belonged to Helen; Menelaus was added later as her husband. In addition, there was a festival at the town, which was called Meneleaeia (Μενελάεια) in honour of Menelaus and Helen. Isocrates writes that at Therapne Helen and Menelaus were worshiped as gods, and not as heroes. Clader argues that, if indeed Helen was worshiped as a goddess at Therapne, then her powers should be largely concerned with fertility, or as a solar deity. There is also evidence for Helen's cult in Hellenistic Sparta: rules for those sacrificing and holding feasts in their honor are extant.

Helen was also worshiped in Attica along with her brothers, and on Rhodes as Helen Dendritis (Helen of the Trees, Έλένα Δενδρῖτις); she was a vegetation or a fertility goddess. Martin P. Nilsson has argued that the cult in Rhodes has its roots to the Minoan, pre-Greek era, when Helen was allegedly worshiped as a vegetation goddess. Claude Calame and other scholars try to analyze the affinity between the cults of Helen and Artemis Orthia, pointing out the resemblance of the terracotta female figurines offered to both deities.

See also

In Spanish: Helena (mitología) para niños

In Spanish: Helena (mitología) para niños

- Astyanassa

- Simon Magus and Helen