Aristophanes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aristophanes

|

|

|---|---|

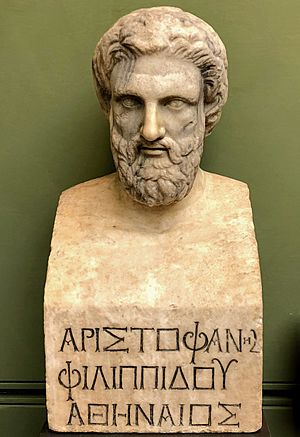

Bust of Aristophanes (1st century AD)

|

|

| Born | c. 446 BC Athens, Greece

|

| Died | c. 386 BC (aged c. 60) Delphi, Greece

|

| Occupation | Playwright (comedy) |

| Years active | 427 BC – 386 BC |

| Known for | Playwright and director of Old Comedy |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Notes | |

|

Although many artists' renderings of Aristophanes portray him with flowing curly hair, several jests in his plays indicate that he may have been prematurely bald.

|

|

Aristophanes (/ˌærɪˈstɒfəniːz/; Ancient Greek: Ἀριστοφάνης, pronounced [aristopʰánɛːs]; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion (Latin: Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his forty plays survive virtually complete. These provide the most valuable examples of a genre of comic drama known as Old Comedy and are used to define it, along with fragments from dozens of lost plays by Aristophanes and his contemporaries.

Also known as "The Father of Comedy" and "the Prince of Ancient Comedy", Aristophanes has been said to recreate the life of ancient Athens more convincingly than any other author. His powers of ridicule were feared and acknowledged by influential contemporaries; Plato singled out Aristophanes' play The Clouds as slander that contributed to the trial and subsequent condemning to death of Socrates, although other satirical playwrights had also caricatured the philosopher.

Aristophanes' second play, The Babylonians (now lost), was denounced by Cleon as a slander against the Athenian polis. It is possible that the case was argued in court, but details of the trial are not recorded and Aristophanes caricatured Cleon mercilessly in his subsequent plays, especially The Knights, the first of many plays that he directed himself. "In my opinion," he says through that play's Chorus, "the author-director of comedies has the hardest job of all."

Contents

Biography

Less is known about Aristophanes than about his plays. In fact, his plays are the main source of information about him and his life. It was conventional in Old Comedy for the chorus to speak on behalf of the author during an address called the parabasis and thus some biographical facts can be found there.

In the absence of clear biographical facts about Aristophanes, scholars make educated guesses based on interpretation of the language in the plays. Inscriptions and summaries or comments by Hellenistic and Byzantine scholars can also provide useful clues. Also, Plato's The Symposium appears to be a useful source of biographical information about Aristophanes, but its reliability is open to doubt.

From the combination of these sources we now that Aristophanes had three sons: Araros, Philippus and a third son, called either Nicostratus or Philetaerus. Araros was also a comic poet who could have been heavily involved in the production of his father's play Wealth II in 388. Araros is thought to have been responsible for the posthumous performances of the now lost plays Aeolosicon II and Cocalus, and it is possible that the last of these won the prize at the City Dionysia in 387. It appears that a second son, Philippus, was twice victorious at the festival in Lenaia and he could have directed some of Eubulus’ comedies. A third son was called either Nicostratus or Philetaerus, and a man by the latter name appears in the catalogue of Lenaia victors with two victories, the first probably in the late 370s.

Aristophanes survived The Peloponnesian War, two oligarchic revolutions and two democratic restorations; this has been interpreted as evidence that he was not actively involved in politics despite his highly political plays. He was probably appointed to the Council of Five Hundred for a year at the beginning of the fourth century but such appointments were very common in democratic Athens.

Use of language

Aristophanes was very conscious of literary fashions and traditions and his plays feature numerous references to other poets. These include not only rival comic dramatists such as Eupolis and Hermippus and predecessors such as Magnes, Crates and Cratinus, but also tragedians, notably Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, all three of whom are mentioned in e.g. The Frogs. Aristophanes was the equal of these great tragedians in his subtle use of lyrics. Also, his plays can be appreciated for their poetic qualities.

A full appreciation of Aristophanes' plays requires an understanding of the poetic forms he employed with virtuoso skill, and of their different rhythms and associations.

It can be argued that the most important feature of the language of the plays is imagery, particularly the use of similes, metaphors and pictorial expressions. In The Knights, for example, the ears of a character with selective hearing are represented as parasols that open and close. In The Frogs, Aeschylus is said to compose verses in the manner of a horse rolling in a sandpit.

Rhetoric

It is widely believed that Aristophanes condemned rhetoric on both moral and political grounds. One of the main reasons why Aristophanes was so against the sophists is that in studying rhetoric money was essential. This meant that roughly all of the pupils studying with the sophists came from upper-class backgrounds and excluded the rest of the polis. Aristophanes believed that education and knowledge was a public service and that anything that excluded willing minds was nothing but an abomination.

Aristophanes and Old Comedy

The plays of Aristophanes are among the defining examples of Old Comedy. For this reason, an understanding of Old Comedy and Aristophanes' place in it is useful to comprehend his plays in their historical and cultural context.

Old Comedy provided a variety of entertainments for a diverse audience. It accommodated a serious purpose, light entertainment, hauntingly beautiful lyrics, the buffoonery of puns and invented words, disciplined verse, wildly absurd plots and a formal, dramatic structure.

In Aristophanic comedy, the hero is an independent-minded and self-reliant individual. He has something of the ingenuity of Homer's Odysseus and much of the shrewdness of the farmer idealized in Hesiod's Works and Days, subjected to corrupt leaders and unreliable neighbours. Typically he devises a complicated and highly fanciful escape from an intolerable situation.

The action of an Aristophanic play obeyed a crazy logic of its own and yet it always unfolded within a formal, dramatic structure that was repeated with minor variations from one play to another. The different, structural elements are associated with different poetic meters and rhythms and these are generally lost in English translations.

Influence and legacy

Latin translations of the plays by Andreas Divus (Venice 1528) were circulated widely throughout Europe in the Renaissance and these were soon followed by translations and adaptations in modern languages. Racine, for example, drew Les Plaideurs (1668) from The Wasps. Goethe (who turned to Aristophanes for a warmer and more vivid form of comedy than he could derive from readings of Terence and Plautus) adapted a short play Die Vögel from The Birds for performance in Weimar.

Aristophanes's plays have a significance that goes beyond their artistic function, as historical documents that open the window on life and politics in classical Athens. The artistic influence of the plays is immeasurable. They have contributed to the history of European theatre and that history in turn shapes our understanding of the plays. The plays are a source of famous sayings, such as "By words the mind is winged."

Interesting facts about Aristophanes

- Aristophanes's name means 'one who appears best', from the greek 'ἄριστος' (Aristos) meaning "best" and 'φαίνομαι', meaning "appear".

- His plays were written for production at the great dramatic festivals of Athens, the Lenaia and City Dionysia, where they were judged and awarded prizes in competition with the works of other comic dramatists.

- In his plays Aristophanes expressed conservative views and respect for the older generation.

- Aristophanes' first three plays were not directed by him.

- He won second prize at the City Dionysia in 427 BC with his first play The Banqueters (now lost). When it was produced, he can hardly have been more than 18 years old.

- Aristophanes won first prize there with his next play, The Babylonians (also now lost).

- It has been inferred from statements in The Clouds and Peace that Aristophanes was prematurely bald.

- Aristophanes was probably victorious at least once at the City Dionysia (with Babylonians in 427) and at least three times at the Lenaia, with The Acharnians in 425, Knights in 424, and Frogs in 405.

- A son of Aristophanes, Araros, was also a comic poet and he could have been heavily involved in the production of his father's play Wealth II in 388.

- The language of Aristophanes' plays, and in Old Comedy generally, was valued by ancient commentators as a model of the Attic dialect.

- Aristophanes' plays were used in the study of rhetoric on the recommendation of Quintilian and by students of the Attic dialect in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries AD.

- It is possible that Plato sent copies of the plays to Dionysius of Syracuse so that he might learn about Athenian life and government.

Works

Surviving plays

Most of these are traditionally referred to by abbreviations of their Latin titles; Latin remains a customary language of scholarship in classical studies.

- The Acharnians (Ἀχαρνεῖς Akharneis; Attic Ἀχαρνῆς; Acharnenses), 425 BC

- The Knights (Ἱππεῖς Hippeis; Attic Ἱππῆς; Latin: Equites), 424 BC

- The Clouds (Νεφέλαι Nephelai; Latin: Nubes), original 423 BC, uncompleted revised version from 419 to 416 BC survives

- The Wasps (Σφῆκες Sphekes; Latin: Vespae), 422 BC

- Peace (Εἰρήνη Eirene; Latin: Pax), first version, 421 BC

- The Birds (Ὄρνιθες Ornithes; Latin: Aves), 414 BC

- Lysistrata (Λυσιστράτη Lysistrate), 411 BC

- Thesmophoriazusae or The Women Celebrating the Thesmophoria (Θεσμοφοριάζουσαι Thesmophoriazousai), first version c.411 BC

- The Frogs (Βάτραχοι Batrakhoi; Latin: Ranae), 405 BC

- Ecclesiazusae or The Assemblywomen; (Ἐκκλησιάζουσαι Ekklesiazousai), c. 392 BC

- Wealth (Πλοῦτος Ploutos; Latin Plutus) second version, 388 BC

Datable non-surviving (lost) plays

The standard modern edition of the fragments is Rudolf Kassel and Colin François Lloyd Austin's, Poetae Comici Graeci III.2.

- Banqueters (Δαιταλεῖς Daitaleis, 427 BC)

- Babylonians (Βαβυλώνιοι Babylonioi, 426 BC)

- Farmers (Γεωργοί Georgoi, 424 BC)

- Merchant Ships (Ὁλκάδες Holkades, 423 BC)

- Clouds (first version, 423 BC)

- Proagon (Προάγων, 422 BC)

- Amphiaraus (Ἀμφιάραος, 414 BC)

- Plutus (Wealth, first version, 408 BC)

- Gerytades (Γηρυτάδης, uncertain, probably 407 BC)

- Cocalus (Κώκαλος, 387 BC)

- Aiolosicon (Αἰολοσίκων, second version, 386 BC)

Undated non-surviving (lost) plays

- Aiolosicon (first version)

- Anagyrus (Ἀνάγυρος)

- Frying-Pan Men (Ταγηνισταί Tagenistai)

- Daedalus (Δαίδαλος)

- Danaids (Δαναΐδες Danaides)

- Centaur (Κένταυρος Kentauros)

- Heroes (Ἥρωες)

- Lemnian Women (Λήμνιαι Lemniai)

- Old Age (Γῆρας Geras)

- Peace (second version)

- Phoenician Women (Φοίνισσαι Phoinissai)

- Polyidus (Πολύιδος)

- Seasons (Ὧραι Horai)

- Storks (Πελαργοί Pelargoi)

- Telmessians (Τελμησσεῖς Telmesseis)

- Triphales (Τριφάλης)

- Thesmophoriazusae (Women at the Thesmophoria Festival, second version)

- Women in Tents (Σκηνὰς Καταλαμβάνουσαι Skenas Katalambanousai)

Attributed (doubtful, possibly by Archippus)

|

|

See also

In Spanish: Aristófanes para niños

In Spanish: Aristófanes para niños

- Hubert Parry wrote music for The Birds

- Theatre of ancient Greece