Herodotus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Herodotus

|

|

|---|---|

| Ἡρόδοτος | |

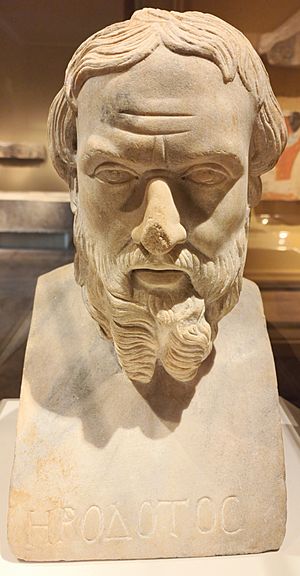

A Roman copy (2nd century CE) of a Greek bust of Herodotus from the first half of the 4th century BCE

|

|

| Born | c. 484 BCE |

| Died | c. 425 BCE (aged approximately 60) |

| Occupation | Historian |

|

Notable work

|

Histories |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

Herodotus (/həˈrɒdətəs/ HƏ-rod-Ə-təs; Ancient Greek: Ἡρόδοτος, romanized: Hēródotos; c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known for having written the Histories – a detailed account of the Greco-Persian Wars. Herodotus was the first writer to perform systematic investigation of historical events. He is referred to as "The Father of History", a title conferred on him by the ancient Roman orator Cicero.

The Histories primarily cover the lives of prominent kings and famous battles such as Marathon, Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, Plataea, and Mycale. His work deviates from the main topics to provide a cultural, ethnographical, geographical, and historiographical background that forms an essential part of the narrative and provides readers with a wellspring of additional information.

Herodotus has been criticized for his inclusion of "legends and fanciful accounts" in his work. The contemporaneous historian Thucydides accused him of making up stories for entertainment. However, Herodotus explained that he reported what he could see and was told. A sizable portion of the Histories has since been confirmed by modern historians and archaeologists.

Contents

Life

Modern scholars generally turn to Herodotus' own writing for reliable information about his life, supplemented with ancient yet much later sources, such as the Byzantine Suda, an 11th-century encyclopedia which possibly took its information from traditional accounts.

Childhood

It is generally accepted that Herodotus was born at Halicarnassus in Anatolia around 485 BCE. The Suda describes his family as influential, and that he was the son of Lyxes and Dryo, and the brother of Theodorus, and that he was also related to Panyassis – an epic poet of the time.

Halicarnassus was within the Persian Empire at that time, making Herodotus a Persian subject, and it may be that the young Herodotus heard local eyewitness accounts of events within the empire and of Persian preparations for the invasion of Greece, including the movements of the local fleet under the command of Artemisia I of Caria.

Inscriptions recently discovered at Halicarnassus indicate that Artemesia's grandson Lygdamis negotiated with a local assembly to settle disputes over seized property, which is consistent with a tyrant under pressure. His name is not mentioned later in the tribute list of the Athenian Delian League, indicating that there might well have been a successful uprising against him sometime before 454 BCE.

Herodotus wrote his Histories in the Ionian dialect, in spite of being born in a Dorian settlement. According to the Suda, Herodotus learned the Ionian dialect as a boy living on the island of Samos, to which he had fled with his family from the oppressions of Lygdamis, tyrant of Halicarnassus and grandson of Artemisia. Panyassis, the epic poet related to Herodotus, is reported to have taken part in a failed uprising.

The Suda also informs us that Herodotus later returned home to lead the revolt that eventually overthrew the tyrant. Due to recent discoveries of inscriptions at Halicarnassus dated to about Herodotus' time, we now know that the Ionic dialect was used in Halicarnassus in some official documents, so there is no need to assume (like the Suda) that he must have learned the dialect elsewhere. The Suda is the only source placing Herodotus as the heroic liberator of his birthplace, casting doubt upon the veracity of that romantic account.

Early travels

As Herodotus himself reveals, Halicarnassus, though a Dorian city, had ended its close relations with its Dorian neighbours after an unseemly quarrel (I, 144), and it had helped pioneer Greek trade with Egypt (II, 178). It was, therefore, an outward-looking, international-minded port within the Persian Empire, and the historian's family could well have had contacts in other countries under Persian rule, facilitating his travels and his researches.

Herodotus' eyewitness accounts indicate that he traveled in Egypt in association with Athenians, probably sometime after 454 BCE or possibly earlier, after an Athenian fleet had assisted the uprising against Persian rule in 460–454 BCE. He probably traveled to Tyre next and then down the Euphrates to Babylon. For some reason, possibly associated with local politics, he subsequently found himself unpopular in Halicarnassus, and sometime around 447 BCE, migrated to Periclean Athens – a city whose people and democratic institutions he openly admired (V, 78). Athens was also the place where he came to know the local topography (VI, 137; VIII, 52–55), as well as leading citizens such as the Alcmaeonids, a clan whose history is featured frequently in his writing.

According to Eusebius and Plutarch, Herodotus was granted a financial reward by the Athenian assembly in recognition of his work. Plutarch, using Diyllus as a source, says this was 10 talents.

Later life

In 443 BCE or shortly afterwards, he migrated to Thurii, in modern Calabria, as part of an Athenian-sponsored colony. Aristotle refers to a version of the Histories written by "Herodotus of Thurium", and some passages in the Histories have been interpreted as proof that he wrote about Magna Graecia from personal experience there (IV, 15,99; VI, 127). Intimate knowledge of some events in the first years of the Peloponnesian War (VI, 91; VII, 133, 233; IX, 73) indicate that he might have returned to Athens, in which case it is possible that he died there during an outbreak of the plague. Possibly he died in Macedonia instead, after obtaining the patronage of the court there; or else he died back in Thurii. There is nothing in the Histories that can be dated to later than 430 BCE with any certainty, and it is generally assumed that he died not long afterwards, possibly before his sixtieth year.

Author and orator

Herodotus would have made his researches known to the larger world through oral recitations to a public crowd. John Marincola writes in his introduction to the Penguin edition of the Histories that there are certain identifiable pieces in the early books of Herodotus' work which could be labeled as "performance pieces". These portions of the research seem independent and "almost detachable", so that they might have been set aside by the author for the purposes of an oral performance. The intellectual matrix of the 5th century, Marincola suggests, comprised many oral performances in which philosophers would dramatically recite such detachable pieces of their work. The idea was to criticize previous arguments on a topic and emphatically and enthusiastically insert their own in order to win over the audience.

It was conventional in Herodotus' day for authors to "publish" their works by reciting them at popular festivals. According to Lucian, Herodotus took his finished work straight from Anatolia to the Olympic Games and read the entire Histories to the assembled spectators in one sitting, receiving rapturous applause at the end of it. According to a very different account by an ancient grammarian, Herodotus refused to begin reading his work at the festival of Olympia until some clouds offered him a bit of shade – by which time the assembly had dispersed. (Hence the proverbial expression "Herodotus and his shade" to describe someone who misses an opportunity through delay.) Herodotus' recitation at Olympia was a favourite theme among ancient writers, and there is another interesting variation on the story to be found in the Suda: that of Photius and Tzetzes, in which a young Thucydides happened to be in the assembly with his father, and burst into tears during the recital. Herodotus observed prophetically to the boy's father, "Your son's soul yearns for knowledge."

Eventually, Thucydides and Herodotus became close enough for both to be interred in Thucydides' tomb in Athens. Such at least was the opinion of Marcellinus in his Life of Thucydides. According to the Suda, he was buried in Macedonian Pella and in the agora in Thurium.

Place in history

Herodotus announced the purpose and scope of his work at the beginning of his Histories:

Predecessors

His record of the achievements of others was an achievement in itself, though the extent of it has been debated. Herodotus' place in history and his significance may be understood according to the traditions within which he worked. His work is the earliest Greek prose to have survived intact. However, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a literary critic of Augustan Rome, listed seven predecessors of Herodotus, describing their works as simple, unadorned accounts of their own and other cities and people, Greek or foreign, including popular legends, sometimes melodramatic and naïve, often charming – all traits that can be found in the work of Herodotus himself.

Modern historians regard the chronology as uncertain, but according to the ancient account, these predecessors included Dionysius of Miletus, Charon of Lampsacus, Hellanicus of Lesbos, Xanthus of Lydia and, the best attested of them all, Hecataeus of Miletus. Of these, only fragments of Hecataeus' works survived, and the authenticity of these is debatable, but they provide a glimpse into the kind of tradition within which Herodotus wrote his own Histories.

Contemporary and modern critics

It is on account of the many strange stories and the folk-tales he reported that his critics have branded him "The Father of Lies". Even his own contemporaries found reason to scoff at his achievement. In fact, one modern scholar has wondered whether Herodotus left his home in Greek Anatolia, migrating westwards to Athens and beyond, because his own countrymen had ridiculed his work, a circumstance possibly hinted at in an epitaph said to have been dedicated to Herodotus at one of his three supposed resting places, Thuria:

Herodotus the son of Sphynx

lies; in Ionic history without peer;

a Dorian born, who fled from slander's brand

and made in Thuria his new native land.

Yet it was in Athens where his most formidable contemporary critics could be found.

The Athenian historian Thucydides dismissed Herodotus as a "logos-writer" (story-teller). Thucydides, who had been trained in rhetoric, became the model for subsequent prose-writers as an author who seeks to appear firmly in control of his material, whereas with his frequent digressions Herodotus appeared to minimize (or possibly disguise) his authorial control. Moreover, Thucydides developed a historical topic more in keeping with the Greek world-view: focused on the context of the polis or city-state. The interplay of civilizations was more relevant to Greeks living in Anatolia, such as Herodotus himself, for whom life within a foreign civilization was a recent memory.

See also

In Spanish: Heródoto para niños

In Spanish: Heródoto para niños

- Al-Masudi, known as the Herodotus of the Arabs

- Herodotus Machine

- Historiography (the history of history and historians)

- Life of Homer (Pseudo-Herodotus)

- Sostratus of Aegina

Critical editions

- C. Hude (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Tomvs prior: Libros I–IV continens. (Oxford 1908)

- C. Hude (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Tomvs alter: Libri V–IX continens. (Oxford 1908)

- H. B. Rosén (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Vol. I: Libros I–IV continens. (Leipzig 1987)

- H. B. Rosén (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Vol. II: Libros V–IX continens indicibus criticis adiectis (Stuttgart 1997)

- N. G. Wilson (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Tomvs prior: Libros I–IV continens. (Oxford 2015)

- N. G. Wilson (ed.) Herodoti Historiae. Tomvs alter: Libri V–IX continens. (Oxford 2015)

Translations

Several English translations of Herodotus' Histories are readily available in multiple editions. The most readily available are those translated by:

- Henry Cary (judge), translation 1849: text Internet Archive

- George Rawlinson, translation 1858–1860. Public domain; many editions available, although Everyman Library and Wordsworth Classics editions are the most common ones still in print.

- George Campbell Macaulay, translation 1890, published in two volumes. London: Macmillan and Co.

- A. D. Godley 1920; revised 1926. Reprinted 1931, 1946, 1960, 1966, 1975, 1981, 1990, 1996, 1999, 2004. Available in four volumes from Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. ISBN: 0-674-99130-3 Printed with Greek on the left and English on the right:

- A. D. Godley Herodotus : The Persian Wars : Volume I : Books 1–2 (Cambridge, Massachusetts 1920)

- A. D. Godley Herodotus : The Persian Wars : Volume II : Books 3–4 (Cambridge, Massachusetts 1921)

- A. D. Godley Herodotus : The Persian Wars : Volume III : Books 5–7 (Cambridge, Massachusetts 1922)

- A. D. Godley Herodotus : The Persian Wars : Volume IV : Books 8–9 (Cambridge, Massachusetts 1925)

- Aubrey de Sélincourt, originally 1954; revised by John Marincola in 1996. Several editions from Penguin Books available.

- David Grene, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Robin Waterfield, with an Introduction and Notes by Carolyn Dewald, Oxford World Classics, 1997. ISBN: 978-0-19-953566-8

- Andrea L. Purvis, The Landmark Herodotus, edited by Robert B. Strassler. Pantheon, 2007. ISBN: 978-0-375-42109-9 with adequate ancillary information.

- Walter Blanco, Herodotus: The Histories: The Complete Translation, Backgrounds, Commentaries. Edited by Jennifer Tolbert Roberts. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

- Tom Holland, The Histories, Herodotus. Introduction and notes by Paul Cartledge. New York, Penguin, 2013.