Francisco Vázquez de Coronado facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado

|

|

|---|---|

Francisco Vázquez Coronado in the Plaza Mayor de Salamanca

|

|

| Governor of New Galicia | |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1510 Salamanca, Crown of Castile |

| Died | 22 September 1554 (aged 43–44) Mexico City, Viceroyalty of New Spain |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1535–1554 |

| Battles/wars | Spanish conquest of Mexico Exploration of North America |

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján (ca. 1510 – September 22, 1554) was a Spanish conquistador, who visited New Mexico and other parts of what are now the southwestern United States between 1540 and 1542. He died in 1554. He married Beatriz De Estrada, the daughter of a colonial treasurer.

Contents

Early life

Vázquez de Coronado was born into a noble family in Salamanca, in 1510 as the second son of Juan Vázquez de Coronado and Isabel de Luján. Juan Vázquez held various positions in the administration of the recently captured Emirate of Granada under Íñigo López de Mendoza, its first Christian governor.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado went to New Spain (present-day Mexico) in 1535 at about age 25, in the entourage of its first Viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, the son of his father's patron and Vázquez de Coronado's personal friend. In New Spain, he married twelve-year-old Beatriz de Estrada, called "the Saint" (la Santa), sister of Leonor de Estrada, ancestor of the de Alvarado family and daughter of Treasurer and Governor Alonso de Estrada y Hidalgo, Lord of Picón, and his wife Marina Flores Gutiérrez de la Caballería, from a converso Jewish family.

Mounting the expedition

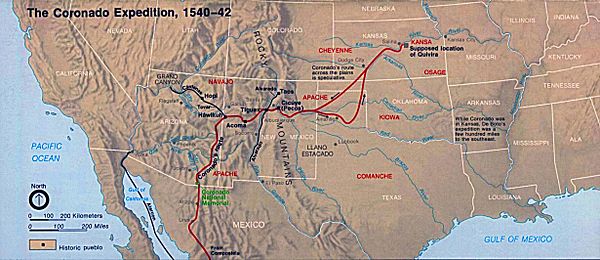

Coronado was governor of Nueva Galicia (New Galicia, the contemporary Mexican states of Jalisco, Sinaloa and Nayarit). As such he had already sent out Friar Marcos de Niza and Narváez expedition survivor Estevanico on a voyage to the north, to New Mexico. When Marcos returned he told about a wealthy, golden city, called Cíbola. He also reported that he traversed the length of the trail, that Estevanico was killed by the Zuni citizens of Cíbola, and though he did not enter the city of Cíbola it was while standing on a high hill he able to observe that the city was made of gold and that he could see the Pacific Ocean off to the West. Based on this report the expedition had two components. One component would travel by sea and would carry the majority of the expeditions supplies. The other component would travel by land along the trail Friar Marcos de Niza traversed. Coronado and Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza invested large sums of private money into the venture, and Mendoza being Coronado's friend and fellow investor appointed him as the commander of an expedition to go and find the seven golden cities and take all of their gold. Coronado set out in 1540, joined by a large expedition of 335 Spanish, 1,300 Mexican Indian allies, four Franciscan monks (the most notable of whom was Juan de Padilla and the newly appointed provincial superior of the Franciscan order in the New World, Marcos de Niza), and several slaves, both native Americans and Africans.

He followed the Sonoran coast northward, keeping the Sea of Cortez to his left. At the last Spanish settlement of San Miguel de Culiacán he rested his expedition before they traveled over the inland trail. Scouts were sent on the trail to investigate the question; "would the land along the route be able to support a large body of soldiers and animals?" The report was that it could not, so Coronado had to divide his expedition into small groups and time their departures so that grazing lands and waterholes along the trail could recover. At intervals along the trail camps were established and garrisoned with soldiers to keep the main supply route open. Once the scouting and planning was done Coronado lead the first group of soldiers on the trail. They were horsemen and foot soldiers who were supposed to travel fast and light, while the main bulk of the expedition would arrive in timed intervals behind them. After leaving the last Spanish settlement they traveled northward through Sonora, and crossed the Gila River, Mogollón Rim, Little Colorado River, and followed the Zuni River drainage into Cíbola, in the west of present-day New Mexico. There he was met by disappointment. Cíbola was nothing like the great golden city fray Marcos had described, it was just regional complex of simple pueblos of the Zuni Indians.

Conquest of Cíbola

Coronado traversed Arizona's Mogollón Rim and from the head waters of the Little Colorado he travel until he came to the Zuni River. He followed that river until he found the region inhabited by the Zunis. The members of the expedition were almost starving and demanded entrance into the village of Hawikuh, and they were denied entrance or trade. Coronado had to enter Hawikuh through force of arms and take the food he needed. The other villages then did not contest Coronado's demands when the Spanish explored them for intelligence and resources, and this consitutes the conquest of Cíbola. In the Hawikuh fight Coronado was injured and he had to stay in the Zuni healing. From the knowledge gathered he sent out several scouting expeditions. The first scouting expedition lead by Pedro de Tovar was headed to the Hopi villages with the expectation that maybe this region may contain the wealthy Cíbola. Upon arrival the Spanish were denied entrance to the first village they came across, and they had to use armed force to enter. Afterwards the remaining villages did not dare to fight the Spanish. Materially the Hopi region was just as poor as the Zuni, but what the Spanish learned was that a large river (the Colorado), lay to the west. The scouting party returned to Zuni and reported their findings, and Coronado sent another scouting expedition lead by Garcia Lopez de Cárdenas to find this river. The second scouting expedition returned to Hopi to acquired scouts and supplies that would be used to find this river. This expedition did find the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, and they became the first Europeans to see the magnificent Grand Canyon. After failing at trying to climb down into the Grand Canyon to the river they reported that they would not be able to use the river to link up with their ships. After this the main body of the expedition began its journey to the next population center of pueblos which were located along the Rio Grande River in New Mexico.

Exploration of the Colorado River

Melchior Díaz was the local commander of a camp along the main supply route. When Coronado was not able to establish contact with the ships from Zuni region, Díaz was detailed to establish contact with Hernando de Alarcón whose fleet was shipping supplies for Coronado. Díaz set out from the valley of Corazones in Sonora and traveled overland in a north and northwesterly direction until he arrived at both junctions of the Colorado river and Gila river. There the local natives told him that Alarcón's sailors had buried supplies and left a note in a bottle. The supplies were retrieved and the note read that they rowed up the river as far as they could go looking for the Coronado expedition but had given up their wait because worms were eating holes in the ships and that the fleet would return to their departure point. Díaz died on the return trip.

The Tiguex War

Hernando de Alvarado was sent east, and found villages around the Rio Grande. Coronado set up his winter quarters in one of them, Tiguex, across the river from present-day Bernalillo near Albuquerque, New Mexico. In the winter of 1540-41 the demands of his army resulted in conflicts with the Rio Grande Indians that led to the brutal Tiguex War, resulting in the destruction of the Tiguex pueblos and the death of hundreds of Indians.

The search for Quivira

An Indian, whom Coronado called the Turk, had told him about Quivira, a rich country in the northwest. Deciding to look for Quivira, he took the Turk as his guide and traversed the Llano Estacado and what is now the Texas Panhandle. However, the Turk was found lying about the route — or at least Coronado supposed he was — and was executed. Other guides led him further to Quivira, and he reached a village near present-day Lindsborg, Kansas. But his disappointment was repeated: the Quivira Indians (later known as Wichita) were no rich people at all, the village consisted mostly of thatched huts, and not even small amounts of gold could be found. Coronado returned to Tiguex, where his main force had remained behind. Here he spent another winter. Near present day Dodge City, Kansas, Coronado held the first Christian Mass in the interior of North America which is presently marked by a large concrete cross called Coronado's Cross to commemorate the event which took place on June 29, 1541.

Return to Mexico

In 1542 Coronado was ordered back to central New Spain so that his troops could help put down the The Mixtón Rebellion. He left two Franciscan missionaries, because they insisted that they stay, and withdrew his forces back to Mexico by roughly the same route he had come. When he arrived back the Mixtón Rebellion was already over. Only 100 of his men came back with him. Although the expedition was a complete failure, he remained governor of New Galicia until 1544, but the expedition had bankrupted him. In 1544, he retired to Mexico City, where he died in 1554.

Family

Within a year of arriving in New Spain, he married Beatriz de Estrada, called "the saint".

Beatriz was the second daughter of Alonso de Estrada and Marina de la Caballería; niece of Diego de Caballeria. The Estrada-Coronado union was a carefully calculated political union that Francisco and Marina orchestrated. Through this marriage, Francisco became a wealthy man. Beatriz brought to the marriage the encomienda of Tlapa, the third largest encomienda in New Spain. This marriage was an important source of funding for Francisco's expedition.

Beatriz and Francisco have been reported, through different sources, to have had at least four sons (Gerónimo, Salvador, Juan, and Alonso) and five daughters (Isabel, María, Luisa, Mariana, and Mayor).

After Alonso's death, Beatriz ensured that three of their daughters were married into prominent families of New Spain. She never remarried.

Beatriz reported that her husband had died in great poverty, since their encomiendas had been taken away from them due to the New Laws, and that she and her daughters lived in misery too, a shame for the widow of a conqueror that had provided such valuable service to his majesty. This, as most reports from the early days of New Spain, both positive and negative and regarding all things, have been proven to be false, part of the power struggles among settlers and attempts to exploit the budding new system that tried to find a way to administer justice in land the king could not see nor the army reach. Francisco, Beatriz and their children actually ended their days comfortably.

Commemoration

In 1939, United States 76th Congress passes the Coronado Exposition Commission Act of 1939 authorizing the erection of a monument at the nearest point of the international boundary between the United States and Mexico where the Coronado expedition first crossed into North America.

In 1952, the United States established Coronado National Memorial near Sierra Vista, Arizona to commemorate his expedition. The nearby Coronado National Forest is also named in his honor.

In 1908, Coronado Butte, a summit in the Grand Canyon, was officially named to commemorate him.

A large hill northwest of Lindsborg, Kansas, is called Coronado Heights.

Coronado High Schools in Lubbock, Texas; El Paso, Texas; Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Scottsdale, Arizona were named for Vázquez de Coronado.

Coronado Road in Phoenix, Arizona, was named after Vázquez de Coronado. Similarly, Interstate 40 through Albuquerque has been named the Coronado Freeway.

Coronado, California is not named after Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, but is named after Coronado Islands, which were named in 1602 by Sebastián Vizcaíno who called them Los Cuatro Coronados (the four crowned ones) to honor four martyrs.

The mineral Coronadite is named after him.

Images for kids

-

Coronado Sets Out to the North (Frederic Remington, c. 1900)

See also

In Spanish: Francisco Vázquez de Coronado para niños

In Spanish: Francisco Vázquez de Coronado para niños