Feud facts for kids

A feud (pronounced /ˈfjuːd/) (also called blood feud or vendetta) is a long-running argument or fight between parties. In most cases it involves whole familles or clans. People are seen as guilty, not because they did something, but because they were seen with other people (who are considered guilty). This is called guilt by association.

Feuds start because one party thinks they were attacked, insulted, or otherwise harmed by the other party. Intense feelings of resentment trigger the initial revenge, which causes the other party to feel the same way. The dispute is then fueled by a long-running cycle of retaliatory violence. This ongoing cycle of provocation and retaliation makes it very difficult to end the feud peacefully. Feuds frequently involve the original parties' family members and/or associates. They can last for generations.

Up to the early modern period, feuds were considered legitimate legal instruments. The state or ruler even made laws for certain aspects of feuds. Once modern centralizing states asserted and enforced a monopoly on legitimate use of force, feuds became illegal and the concept acquired its current negative connotation.

Contents

Blood feuds/vendetta

A blood feud is a feud with a cycle of retaliatory violence, with the relatives of someone who has been killed or otherwise wronged or dishonored. The wronged person then wants vengeance and kills the culprits or punishes them in other ways. If he cannot get the culprits, he does this to their relatives. Historically, the word vendetta has been used to mean a blood feud. The word is Italian, and originates from the Latin vindicta, "vengeance." In modern times, the word also means any other long-standing feud, not necessarily involving bloodshed.

Vendetta history

Originally, a vendetta was a blood feud between two families. Kinsmen of the victim wanted to take revenge for his or her death by killing either those responsible for the killing or some of their relatives. Usually, the closest male relative of the person killed or wronged maintains the vendetta, but other members of the family may do so as well. If the culprit had disappeared or was already dead, the vengeance could extend to other relatives.

Vendetta is typical of societies with a weak rule of law or in those where the state does not consider itself responsible for helping with this kind of dispute. In such societies, family and kinship ties are the main source of authority. An entire family is considered responsible for whatever one of them has done. Sometimes even two separate branches of the same family could come to blows over some matter.

Today, the practice of vendetta has almost disappeared in societies where law enforcement works. There, criminal law punishes lawbreakers.

In ancient Homeric Greece, the practice of personal vengeance against wrongdoers was considered natural and customary: "Embedded in the Greek morality of retaliation is the right of vendetta . . . Vendetta is a war, just as war is an indefinite series of vendettas; and such acts of vengeance are sanctioned by the gods".

The Ancient Hebrew tribes considered it to be the duty of the individual and family to avenge evil in God's name.

According to medievalist Marc Bloch, "The Middle Ages, from beginning to end, and particularly the feudal era, lived under the sign of private vengeance.

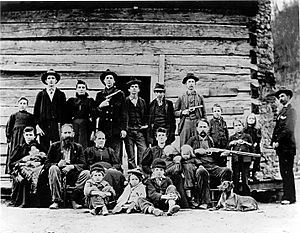

The Celtic phenomenon of the blood feud demanded "an eye for an eye," and usually descended into murder. Disagreements between clans might last for generations in Scotland and Ireland. Due to the Celtic heritage of many whites living in Appalachia, a series of prolonged violent engagements in late- nineteenth-century Kentucky and West Virginia were referred to commonly as feuds, a tendency that was partly due to the nineteenth-century popularity of William Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott, authors who both wrote semi-historical accounts of blood feuds.

These incidents, the most famous of which was the Hatfield-McCoy feud, were regularly featured in the newspapers of the eastern U.S. between the 1880s and the early twentieth century. Although they were interpreted as such at the time, there is little reason to believe that these American incidents had any correlation to "feuding" in Europe centuries earlier.

Chariot racing in the Byzantine Empire also included the racing clubs. The Blues and the Greens were more than simply sports teams. They gained influence in military, political, and theological matters. The Blue-Green rivalry often erupted into gang warfare, and street violence had been on the rise in the reign of Justin I. Riots culminated in the Nika riots of 532 AD during the reign of Justinian I, with nearly half the city being burned or destroyed and tens of thousands of people killed.

The Central Asian plateau (north of China) at the time of Genghis Khan's youth was divided into several nomadic tribes or confederations—among them Naimans, Merkits, Uyghurs, Tatars, Mongols, and Keraits—that were all prominent in their own right and often unfriendly toward each other, as evidenced by frequent raids, revenges, and plundering.

In Japan's feudal past the Samurai class upheld the honor of their family, clan, or their lord by katakiuchi (敵討ち), or revenge killings. These killings could also involve the relatives of an offender. While some vendettas were punished by the government, such as that of the 47 Ronin, others were given official permission with specific targets.

At the Holy Roman Empire's Reichstag at Worms in 1495 the right of waging feuds was abolished. However, it took a few more decades until the new regulation was universally accepted.

In Corsica, vendetta was a social code that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged the family honor. It has been estimated that between 1683 and 1715, nearly 30,000 out of 120,000 Corsicans lost their lives to vendetta.

Throughout history, the Maniots—one of Greece's toughest populations—have been known by their neighbors and their enemies as fearless warriors who practice blood feuds. Some vendettas went on for months and sometimes years. The families involved would lock themselves in their towers and when they got the chance would murder members of the opposing family.

The Basque Country in the Late Middle Ages was ravaged by bitter partisan wars between local ruling families. In Navarre, these conflicts became polarised in a violent struggle between the Agramont and Beaumont parties. In Biscay, the two major warring factions were named Oinaz and Gamboa. (Cf. the Guelphs and Ghibellines in Italy). High defensive structures ("towers") built by local noble families, few of which survive today, were frequently razed by fires, sometimes by royal decree.

Leontiy Lyulye, an expert on conditions in the Caucasus, wrote in the mid-19th century: "Among the mountain people the blood feud is not an uncontrollable permanent feeling such as the vendetta is among the Corsicans. It is more like an obligation imposed by the public opinion." In the Dagestani aul Kadar, one such blood feud between two antagonistic clans lasted for nearly 260 years, from the 17th century till the 1860s.

An alternative to feud was blood money (or weregild in the Norse culture), which demanded payment of some kind from those responsible for a wrongful death (even an accidental one). If these payments were not made or were refused by the offended party, a blood feud would ensue.

Vendetta in modern times

Vendetta is reputedly still practiced in some areas in France (especially Corsica) and Italy (especially Sicily, Sardinia, Campania, Calabria, Apulia, and other areas of Southern Italy), in Crete (Greece), among Kurdish clans in Iraq and Turkey, in northern Albania, among Pashtuns in Afghanistan, among Somali clans, over land in Nigeria, in India (a caste-related feuds among rival Hindu groups), between rival tribes in the north-east Indian state of Assam, among rival clans in China and Philippines, among the Arab Bedouins and Arab tribes inhabiting the mountains of Yemen and between Shiites and Sunnis in Iraq, in southern Ethiopia, among the highland tribes of New Guinea, in Svaneti, in the mountainous areas of Dagestan, many northern areas of Georgia and Azerbaijan, a number of republics of the northern Caucasus and essentially among Chechen teips where those seeking retribution do not accept or respect the local law enforcement authority. Vendettas are generally abetted by a perceived or actual indifference on behalf of local law enforcement.

In Albania, the blood feud has returned in rural areas after more than 40 years of being abolished by Albanian communists led by Enver Hoxha. More than 5,500 Albanian families are currently engaged in blood feuds. There are now more than 20,000 men and boys who live under an ever-present death sentence because of blood feuds. Since 1992, at least 10,000 Albanians have been killed due to blood feuds.

Mutual vendetta may develop into a vicious circle of further killings, retaliation, counterattacks, and all-out warfare that can end in the mutual extinction of both families. Often the original cause is forgotten, and feuds continue simply because it is perceived that there has always been a feud.

There is a scene in The Godfather, in which Michael Corleone, hiding from U.S. police in Sicily, walks through a village with his two bodyguards. Michael asks, "Where are all the men?" The bodyguard replies, "They're all dead from vendettas."

Some of the gang wars between organized crime groups are effectively forms of vendetta, where the criminal organization (like the Mafia "family") has taken the place of blood relatives.

Other pages

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Faidas para niños

In Spanish: Faidas para niños