European badger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids European badgerTemporal range: Mid-Pleistocene–Recent

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Meles

|

| Species: |

M. meles

|

| Binomial name | |

| Meles meles (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

|

|

| European badger range | |

The European badger (Meles meles) is a species of badger. Its genus is Meles. It is native to almost all of Europe. It is classed as Least Concern for extinction by the IUCN because of its wide distribution and large population.

The European badger is a social, burrowing animal. It eats a wide variety of plants and animals. It is very fussy over the cleanliness of its burrow, and defecates in latrines. It is known of European badgers that they bury their dead family members. Although they are ferocious when provoked, the European badger is generally a peaceful animal. It has been known to share its burrows with other species such as rabbits, red foxes and raccoon dogs. Although it does not usually prey on domestic animals, the species is sometimes reported to damage livestock through spreading bovine tuberculosis.

Contents

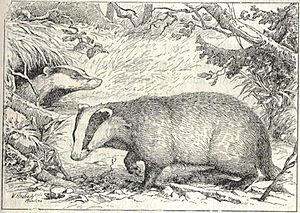

Description

European badgers are powerfully built animals with small heads, thick, short necks, stocky, wedge-shaped bodies and short tails. Their feet are plantigrade or semidigitigrade and short, with five toes on each foot. The limbs are short and massive, with naked lower surfaces on the feet. The claws are strong, elongated and have an obtuse end, which assists in digging. The claws are not retractable, and the hind claws wear with age. Old badgers sometimes have their hind claws almost completely worn away from constant use. Their snouts, which are used for digging and probing, are muscular and flexible. The eyes are small and the ears short and tipped with white. Whiskers are present on the snout and above the eyes. Boars typically have broader heads, thicker necks and narrower tails than sows, which are sleeker, have narrower, less domed heads and fluffier tails. The guts of badgers are longer than those of red foxes, reflecting their omnivorous diet. The small intestine has a mean length of 5.36 metres (17.6 ft) and lacks a cecum. Both sexes have three pairs of nipples but these are more developed in females. European badgers cannot flex their backs as martens, polecats and wolverines can, nor can they stand fully erect like honey badgers, though they can move quickly at full gallop. Adults measure 25–30 cm (9.8–11.8 in) in shoulder height, 60–90 cm (24–35 in) in body length, 12–24 cm (4.7–9.4 in) in tail length, 7.5–13 cm (3.0–5.1 in) in hind foot length and 3.5–7 cm (1.4–2.8 in) in ear height. Males (or boars) slightly exceed females (or sows) in measurements, but can weigh considerably more. Their weights vary seasonally, growing from spring to autumn and reaching a peak just before the winter. During the summer, European badgers commonly weigh 7–13 kg (15–29 lb) and 15–17 kg (33–37 lb) in autumn. The average weight of adults in Białowieża Forest, Poland were 10.2 kg (22 lb) in spring but weighed up to 19 kg (42 lb) in autumn, 46% higher than their spring low mass. In Woodchester Park, England, adults in spring weighed on average 7.9 kg (17 lb) and in fall average 9.5 kg (21 lb). In Doñana National Park, average weight of adult badgers is reported as 6 to 7.95 kg (13.2 to 17.5 lb), perhaps in accordance with Bergmann's rule, that its size decreases in relatively warmer climates closer to the equator. Sows can attain a top autumn weight of around 17.2 kg (38 lb), while exceptionally large boars have been reported in autumn. The heaviest verified was 27.2 kg (60 lb), though unverified specimens have been reported to 30.8 kg (68 lb) and even 34 kg (75 lb) (if so, the heaviest weight for any terrestrial mustelid). If average weights are used, the European badger ranks as the second largest terrestrial mustelid, behind only the wolverine. Although their sense of smell is acute, their eyesight is monochromatic as has been shown by their lack of reaction to red lanterns. Only moving objects attract their attention. Their hearing is no better than that of humans.

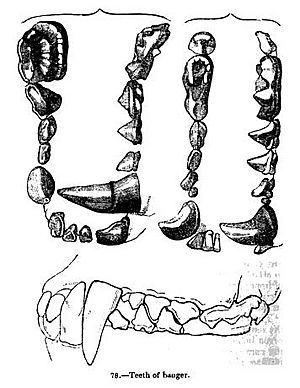

European badger skulls are quite massive, heavy and elongated. Their braincases are oval in outline, while the facial part of their skulls is elongated and narrow. Adults have prominent sagittal crests which can reach 15 mm tall in old males, and are more strongly developed than those of honey badgers. Aside from anchoring the jaw muscles, the thickness of the crests protect their skulls from hard blows. Similar to martens, the dentition of European badgers is well-suited for their omnivorous diets. Their incisors are small and chisel-shaped, their canine teeth are prominent and their carnassials are not overly specialised. Their molars are flattened and adapted for grinding. Their jaws are powerful enough to crush most bones; a provoked badger was once reported as biting down on a man's wrist so severely that his hand had to be amputated. The dental formula is:

| Dentition |

|---|

| 3.1.3.1 |

| 3.1.4.2 |

Scent glands are present below the base of the tail and on the anus. The subcaudal gland secretes a musky-smelling, cream-coloured fatty substance, while the anal glands secrete a stronger-smelling, yellowish-brown fluid.

Fur

In winter, the fur on the back and flanks is long and coarse, consisting of bristly guard hairs with a sparse, soft undercoat. The belly fur consists of short, sparse hairs, with skin being visible in the inguinal region. Guard hair length on the middle of the back is 75–80 mm (3.0–3.1 in) in winter. Prior to the winter, the throat, lower neck, chest and legs are black. The belly is of a lighter, brownish tint, while the inguinal region is brownish-grey. The general colour of the back and sides is light silvery-grey, with straw-coloured highlights on the sides. The tail has long and coarse hairs, and is generally the same colour as the back. Two black bands pass along the head, starting from the upper lip and passing upwards to the whole base of the ears. The bands sometimes extend along the neck and merge with the colour of the upper body. The front parts of the bands are 15 mm (0.6 in), and widen to 45–55 mm (1.8–2.2 in) in the ear region. A wide, white band extends from the nose tip through the forehead and crown. White markings occur on the lower part of the head, and extend backwards to a great part of the neck's length. The summer fur is much coarser, shorter and sparser, and is deeper in colour, with the black tones becoming brownish, sometimes with yellowish tinges. Partial melanism in badgers is known, and albinos are not uncommon. Albino badgers can be pure white or yellowish with pink eyes. Erythristic badgers are more common than the former, being characterised by having a sandy-red colour on the usually black parts of the body. Yellow badgers are also known.

Behaviour

Social and territorial behaviours

European badgers are the most social of badgers, forming groups of six adults on average, though larger associations of up to 23 individuals have been recorded. Group size may be related to habitat composition. Under optimal conditions, badger territories can be as small as 30 ha, but may be as large as 150 ha in marginal areas. Badger territories can be identified by the presence of communal latrines and well-worn paths. It is mainly males that are involved in territorial aggression. A hierarchical social system is thought to exist among badgers and large powerful boars seem to assert dominance over smaller males. Large boars sometimes intrude into neighbouring territories during the main mating season in early spring. Sparring and more vicious fights generally result from territorial defence in the breeding season. However, in general, animals within and outside a group show considerable tolerance of each other. Boars tend to mark their territories more actively than sows, with their territorial activity increasing during the mating season in early spring. Badgers groom each other very thoroughly with their claws and teeth. Grooming may have a social function. They are crepuscular and nocturnal in habits. Aggression among badgers is largely associated with territorial defence and mating. When fighting, they bite each other on the neck and rump, while running and chasing each other and injuries incurred in such fights can be severe and sometimes fatal. When attacked by dogs badgers may raise their tails and fluff up their fur.

European badgers have an extensive vocal repertoire. When threatened they emit deep growls and when fighting make low kekkering noises. They bark when surprised, whicker when playing or in distress, and emit a piercing scream when alarmed or frightened.

Reproduction and development

The average litter consists of one to five cubs. Although many cubs are sired by resident males, up to 54% can be fathered by boars from different colonies. Dominant sows may kill the cubs of subordinates. Cubs are born pink, with greyish, silvery fur and fused eyelids. Neonatal badgers are 12 cm (5 in) in body length on average and weigh 75 to 132 grams (2.6 to 4.7 oz), with cubs from large litters being smaller. By three to five days, their claws become pigmented, and individual dark hairs begin to appear. Their eyes open at four to five weeks and their milk teeth erupt about the same time. They emerge from their setts at eight weeks of age, and begin to be weaned at twelve weeks, though they may still suckle until they are four to five months old. Subordinate females assist the mother in guarding, feeding and grooming the cubs. Cubs fully develop their adult coats at six to nine weeks. In areas with medium to high badger populations, dispersal from the natal group is uncommon, though badgers may temporarily visit other colonies. Badgers can live for up to about fifteen years in the wild.

Denning behaviours

Like other badger species, European badgers are burrowing animals. However, the dens they construct (called setts) are the most complex, and are passed on from generation to generation. The number of exits in one sett can vary from a few to fifty. These setts can be vast, and can sometimes accommodate multiple families. When this happens, each family occupies its own passages and nesting chambers. Some setts may have exits which are only used in times of danger or play. A typical passage has a 22–63 cm (8.7–24.8 in) wide base and a 14–32 cm (5.5–12.6 in) height. Three sleeping chambers occur in a family unit, some of which are open at both ends. The nesting chamber is located 5–10 m (5.5–10.9 yd) from the opening, and is situated more than a 1 m (1.1 yd) underground, in some cases 2.3 m (2.5 yd). Generally, the passages are 35–81 m (38–89 yd) long. The nesting chamber is on average 74 cm × 76 cm (29 in × 30 in), and are 38 cm (15 in) high. Badgers dig and collect bedding throughout the year, particularly in autumn and spring. Sett maintenance is usually carried out by subordinate sows and dominant boars. The chambers are frequently lined with bedding, brought in on dry nights, which consists of grass, bracken, straw, leaves and moss. Up to 30 bundles can be carried to the sett on a single night. European badgers are fastidiously clean animals which regularly clear out and discard old bedding. During the winter, they may take their bedding outside on sunny mornings and retrieve it later in the day. Spring cleaning is connected with the birth of cubs, and may occur several times during the summer to prevent parasite levels building up. If a badger dies within the sett, its conspecifics will seal off the chamber and dig a new one. Some badgers will drag their dead out of the sett and bury them outside. A sett is almost invariably located near a tree, which is used by badgers for stretching or claw scraping. Badgers defecate in latrines, which are located near the sett and at strategic locations on territorial boundaries or near places with abundant food supplies. In extreme cases, when there is a lack of suitable burrowing grounds, badgers may move into haystacks in winter. They may share their setts with red foxes or European rabbits. The badgers may provide protection for the rabbits against other predators. The rabbits usually avoid predation by the badgers by inhabiting smaller, hard to reach chambers.

Winter sleep

Badgers begin to prepare for winter sleep during late summer by accumulating fat reserves, which reach a peak in October. During this period, the sett is cleaned and the nesting chamber is filled with bedding. Upon retiring to sleep, badgers block their sett entrances with dry leaves and earth. They typically stop leaving their setts once snow has fallen. In Russia, badgers retire for their winter sleep from late October to mid-November and emerge from their setts in March and early April. In areas such as England and Transcaucasia, where winters are less harsh, badgers either forgo winter sleep entirely or spend long periods underground, emerging in mild spells.

Diet

Along with brown bears, European badgers are among the least carnivorous members of the Carnivora; they are highly adaptable and opportunistic omnivores, whose diet encompasses a wide range of animals and plants. Earthworms are their most important food source, followed by large insects, carrion, cereals, fruit and small mammals including rabbits, mice, shrews, moles and hedgehogs. Insect prey includes chafers, dung and ground beetles, caterpillars, leatherjackets, and the nests of wasps and bumblebees. They are able to destroy wasp nests, consuming the occupants, combs, and envelope, such as that of Vespula rufa nests, since thick skin and body hair protect the badgers from stings. Cereal food includes wheat, oats, maize and occasionally barley. Fruits include windfall apples, pears, plums, blackberries, bilberries, raspberries, strawberries, acorns, beechmast, pignuts and wild arum corms.

Occasionally, they feed on medium to large birds, amphibians, small reptiles, including tortoises, snails, slugs, fungi, and green food such as clover and grass, particularly in winter and during droughts. Badgers characteristically capture large numbers of one food type in each hunt. Generally, they do not eat more than 0.5 kg (1.1 lb) of food per day, with young specimens yet to attain one year of age eating more than adults. An adult badger weighing 15 kg (33 lb) eats a quantity of food equal to 3.4% of its body weight. Badgers typically eat prey on the spot, and rarely transport it to their setts. Surplus killing has been observed in chicken coops.

Badgers prey on rabbits throughout the year, especially during times when their young are available. They catch young rabbits by locating their position in their nest by scent, then dig vertically downwards to it. In mountainous or hilly districts, where vegetable food is scarce, badgers rely on rabbits as a principal food source. Adult rabbits are usually avoided, unless they are wounded or caught in traps. They consume them by turning them inside out and eating the meat, leaving the inverted skin uneaten. Hedgehogs are eaten in a similar manner. In areas where badgers are common, hedgehogs are scarce. Some rogue badgers may kill lambs, though this is very rare; they may be erroneously implicated in lamb killings through the presence of discarded wool and bones near their setts, though foxes, which occasionally live alongside badgers, are often the culprits, as badgers do not transport food to their earths. They typically kill lambs by biting them behind the shoulder. Poultry and game birds are also taken only rarely. Some badgers may build their setts in close proximity to poultry or game farms without ever causing damage. In the rare instances in which badgers do kill reared birds, the killings usually occur in February–March, when food is scarce due to harsh weather and increases in badger populations. Badgers can easily breach bee hives with their jaws, and are mostly indifferent to bee stings, even when set upon by swarms.

Relationships with other non-human predators

European badgers have few natural enemies. Wolves, lynxes and dogs can pose a threat to badgers, though deaths caused by them are rare. They may live alongside red foxes in isolated sections of large burrows. The two species possibly tolerate each other out of commensalism; foxes provide badgers with food scraps, while badgers maintain the shared burrow's cleanliness. However, cases are known of badgers driving vixens from their dens and destroying their litters without eating them. Raccoon dogs may extensively use badger setts for shelter. There are many known cases of badgers and raccoon dogs wintering in the same hole, possibly because badgers enter hibernation two weeks earlier than the latter, and leave two weeks later. In exceptional cases, badger and raccoon dog cubs may coexist in the same burrow. Badgers may drive out or kill raccoon dogs if they overstay their welcome.

Distribution and habitat

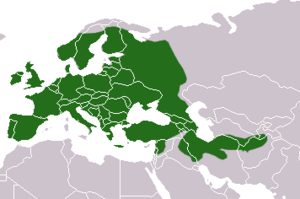

The European badger is native to most of Europe and parts of western Asia. In Europe its range includes Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Crete, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and Ukraine. In Asia it occurs in Afghanistan, China (Xinjiang), Iran, Iraq and Israel.

The distributional boundary between the ranges of European and Asian badgers is the Volga River, the European species being situated on the western bank. They are common in European Russia, with 30,000 individuals having been recorded there in 1990. They are abundant and increasing throughout their range, partly due to a reduction in rabies in Central Europe. In the UK, badgers experienced a 77% increase in numbers during the 1980s and 1990s. The badger population in Great Britain in 2012 is estimated to be 300,000.

The European badger is found in deciduous and mixed woodlands, clearings, spinneys, pastureland and scrub, including Mediterranean maquis shrubland. It has adapted to life in suburban areas and urban parks, although not to the extent of red foxes. In mountainous areas it occurs up to an altitude of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft).

Badger tracking to study their behavior and territories has been done in Ireland using Global Positioning Systems.

Relationships with humans

In folklore and literature

Badgers play a part in European folklore and are featured in modern literature. In Irish mythology, badgers are portrayed as shape-shifters and kinsmen to Tadg, the king of Tara and foster father of Cormac mac Airt. In one story, Tadg berates his adopted son for having killed and prepared some badgers for dinner. In German folklore, the badger is portrayed as a cautious, peace-loving Philistine, who loves more than anything his home, family and comfort, though he can become aggressive if surprised. He is a cousin of Reynard the Fox, whom he uselessly tries to convince to return to the path of righteousness.

In Kenneth Graham's The Wind in the Willows, Mr. Badger is depicted as a gruff, solitary figure who "simply hates society", yet is a good friend to Mole and Ratty. As a friend of Toad's now-deceased father, he is often firm and serious with Toad, but at the same time generally patient and well-meaning towards him. He can be seen as a wise hermit, a good leader and gentleman, embodying common sense. He is also brave and a skilled fighter, and helps rid Toad Hall of invaders from the wild wood.

The "Frances" series of children's books by Russell and Lillian Hoban depicts an anthropomorphic badger family.

In T.H. White's Arthurian series The Once and Future King, the young King Arthur is transformed into a badger by Merlin as part of his education. He meets with an older badger who tells him "I can only teach you two things - to dig, and love your home."

A villainous badger named Tommy Brock appears in Beatrix Potter's 1912 book The Tale of Mr. Tod. He is shown kidnapping the children of Benjamin Bunny and his wife Flopsy, and hiding them in an oven at the home of Mr. Tod the fox, whom he fights at the end of the book. The portrayal of the badger as a filthy animal which appropriates fox dens was criticised from a naturalistic viewpoint, though the inconsistencies are few and employed to create individual characters rather than evoke an archetypical fox and badger. A wise old badger named Trufflehunter appears in C. S. Lewis' Prince Caspian, where he aids Caspian X in his struggle against King Miraz.

A badger takes a prominent role in Colin Dann's The Animals of Farthing Wood series as second in command to Fox. The badger is also the house symbol for Hufflepuff in the Harry Potter book series. The Redwall series also has the Badger Lords, who rule the extinct volcano fortress of Salamandastron and are renowned as fierce warriors. The children's television series Bodger & Badger was popular on CBBC during the 1990s and was set around the mishaps of a mashed potato-loving badger and his human companion.

Hunting

European badgers are of little significance to hunting economies, though they may be actively hunted locally. Methods used for hunting badgers include catching them in jaw traps, ambushing them at their setts with guns, smoking them out of their earths and through the use of specially bred dogs such as Fox Terriers and Dachshunds to dig them out. Badgers are, however, notoriously durable animals; their skins are thick, loose and covered in long hair which acts as protection, and their heavily ossified skulls allow them to shrug off most blunt traumas, as well as shotgun pellets.

Domestication

There are several accounts of European badgers being tamed. Tame badgers can be affectionate pets, and can be trained to come to their owners when their names are called. They are easily fed, as they are not fussy eaters, and will instinctively unearth rats, moles and young rabbits without training, though they do have a weakness for pork. Although there is one record of a tame badger befriending a fox, they generally do not tolerate the presence of cats and dogs, and will chase them.

Uses

The hair of the European badger has been used for centuries for making sporrans and high end shaving brushes. Sporrans are traditionally worn as part of male Scottish highland dress. They form a bag or pocket made from a pelt and a badger or other animal's mask may be used as a flap. Compared to the fur of other animals, badger's hair is ideal for shaving brushes because it retains the hot water that needs to be applied to the skin while wet shaving. Although some brushes are made from wild badger hair, most hair is sourced from China where badgers are farmed for this purpose. The pelt was also formerly used for pistol furniture.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tejón europeo para niños

In Spanish: Tejón europeo para niños