Dengue facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dengue fever |

|

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Dengue, breakbone fever |

|

|

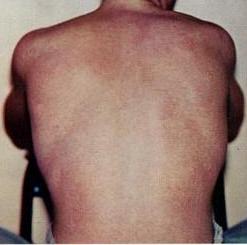

| The typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash |

| Complications | Bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, dangerously low blood pressure |

| Usual onset | 3–14 days after exposure |

| Duration | 2–7 days |

| Causes | Dengue virus by Aedes mosquitos |

| Diagnostic method | Detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA |

| Similar conditions | Malaria, yellow fever, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis |

| Prevention | Dengue fever vaccine, decreasing mosquito exposure |

| Treatment | Supportive care, intravenous fluids, blood transfusions |

| Frequency | 390 million per year |

| Deaths | ~40,000 (2017) |

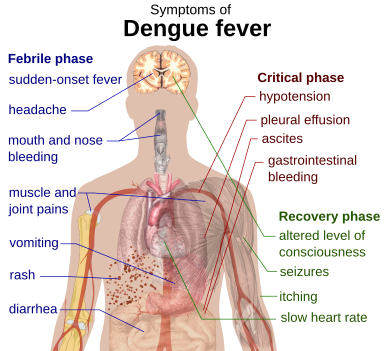

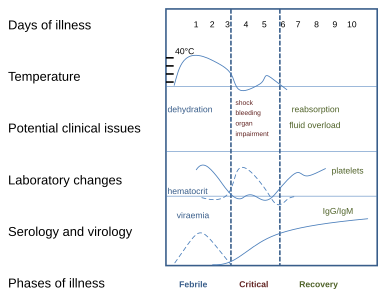

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin itching and skin rash. Recovery generally takes two to seven days. In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into a more severe dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage, or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, principally Aedes aegypti. The virus has five serotypes; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications. A number of tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA.

Two types of dengue vaccine have been approved and are commercially available. On 5 December 2022 the European Medicines Agency approved Qdenga, a live tetravalent attenuated vaccine for adults, adolescents and kids from four years of age. The 2016 vaccine Dengvaxia is only recommended in individuals who have been previously infected, or in populations with a high rate of prior infection by age nine. Other methods of prevention include reducing mosquito habitat and limiting exposure to bites. This may be done by getting rid of or covering standing water and wearing clothing that covers much of the body. Treatment of acute dengue is supportive and includes giving fluid either by mouth or intravenously for mild or moderate disease. For more severe cases, blood transfusion may be required. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is recommended instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for fever reduction and pain relief in dengue due to an increased risk of bleeding from NSAID use.

The earliest descriptions of an outbreak date from 1779. Its viral cause and spread were understood by the early 20th century. Dengue has become a global problem since the Second World War and is common in more than 120 countries, mainly in Southeast Asia, South Asia and South America. About 390 million people are infected per year, about half a million require hospital admission, and approximately 40,000 die. In 2019, a significant increase in the number of cases was seen. Apart from eliminating the mosquitos, work is ongoing for medication targeted directly at the virus. It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.

Contents

Signs and symptoms

Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic (80%) or have only mild symptoms such as an uncomplicated fever. Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening. The incubation period (time between exposure and onset of symptoms) ranges from 3 to 14 days, but most often it is 4 to 7 days. Therefore, travelers returning from endemic areas are unlikely to have dengue fever if symptoms start more than 14 days after arriving home. Children often experience symptoms similar to those of the common cold and gastroenteritis (vomiting and diarrhea) and have a greater risk of severe complications, though initial symptoms are generally mild but include high fever.

Cause

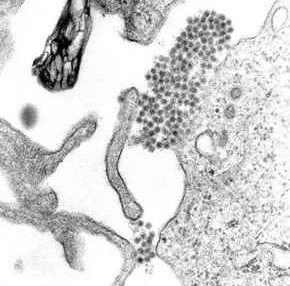

Dengue virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitos, particularly A. aegypti. These mosquitos usually live between the latitudes of 35° North and 35° South below an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft). They typically bite during the early morning and in the evening, but they may bite and thus spread infection at any time of day. Other Aedes species that transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis and A. scutellaris. Humans are the primary host of the virus, but it also circulates in nonhuman primates. An infection can be acquired via a single bite. A female mosquito that takes a blood meal from a person infected with dengue fever, during the initial 2- to 10-day febrile period, becomes itself infected with the virus in the cells lining its gut. About 8–10 days later, the virus spreads to other tissues including the mosquito's salivary glands and is subsequently released into its saliva. The virus seems to have no detrimental effect on the mosquito, which remains infected for life. Aedes aegypti is particularly involved, as it prefers to lay its eggs in artificial water containers, to live in close proximity to humans, and to feed on people rather than other vertebrates.

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.

When a mosquito carrying dengue virus bites a person, the virus enters the skin together with the mosquito's saliva. It binds to and enters white blood cells, and reproduces inside the cells while they move throughout the body. The white blood cells respond by producing several signaling proteins, such as cytokines and interferons, which are responsible for many of the symptoms, such as the fever, the flu-like symptoms, and the severe pains. In severe infection, the virus production inside the body is greatly increased, and many more organs (such as the liver and the bone marrow) can be affected.

Diagnosis

|

Warning signs

|

||||

| Worsening abdominal pain | ||||

| Ongoing vomiting | ||||

| Liver enlargement | ||||

| Mucosal bleeding | ||||

| High hematocrit with low platelets | ||||

| Lethargy or restlessness | ||||

| Serosal effusions | ||||

The diagnosis of dengue is typically made clinically, on the basis of reported symptoms and physical examination.

Prevention

Prevention depends on control of and protection from the bites of the mosquito that transmits it. The World Health Organization recommends an Integrated Vector Control program consisting of five elements:

- Advocacy, social mobilization and legislation to ensure that public health bodies and communities are strengthened;

- Collaboration between the health and other sectors (public and private);

- An integrated approach to disease control to maximize the use of resources;

- Evidence-based decision making to ensure any interventions are targeted appropriately; and

- Capacity-building to ensure an adequate response to the local situation.

The primary method of controlling A. aegypti is by eliminating its habitats. This is done by getting rid of open sources of water, or if this is not possible, by adding insecticides or biological control agents to these areas. Generalized spraying with organophosphate or pyrethroid insecticides, while sometimes done, is not thought to be effective. Reducing open collections of water through environmental modification is the preferred method of control, given the concerns of negative health effects from insecticides and greater logistical difficulties with control agents. People can prevent mosquito bites by wearing clothing that fully covers the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective). While these measures can be an effective means of reducing an individual's risk of exposure, they do little in terms of mitigating the frequency of outbreaks, which appear to be on the rise in some areas, probably due to urbanization increasing the habitat of A. aegypti. The range of the disease also appears to be expanding possibly due to climate change.

Anti-dengue day

International Anti-Dengue Day is observed every year on 15 June. The idea was first agreed upon in 2010 with the first event held in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 2011. Further events were held in 2012 in Yangon, Myanmar, and in 2013 in Vietnam. Goals are to increase public awareness about dengue, mobilize resources for its prevention and control and, to demonstrate the Southeast Asian region's commitment in tackling the disease.

Management

There are no specific antiviral drugs for dengue; however, maintaining proper fluid balance is important. Treatment depends on the symptoms. Those who can drink, are passing urine, have no "warning signs" and are otherwise healthy can be managed at home with daily follow-up and oral rehydration therapy. Those who have other health problems, have "warning signs", or cannot manage regular follow-up should be cared for in hospital. In those with severe dengue care should be provided in an area where there is access to an intensive care unit.

Prognosis

Most people with dengue recover without any ongoing problems. The risk of death among those with severe dengue is 0.8% to 2.5%, and with adequate treatment this is less than 1%. However, those who develop significantly low blood pressure may have a fatality rate of up to 26%. The risk of death among children less than five years old is four times greater than among those over the age of 10. Elderly people are also at higher risk of a poor outcome.

History

The first record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a Chinese medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (266–420) which referred to a "water poison" associated with flying insects. The primary vector, A. aegypti, spread out of Africa in the 15th to 19th centuries due in part to increased globalization secondary to the slave trade. There have been descriptions of epidemics in the 17th century, but the most plausible early reports of dengue epidemics are from 1779 and 1780, when an epidemic swept across Southeast Asia, Africa and North America. From that time until 1940, epidemics were infrequent.

In 1906, transmission by the Aedes mosquitos was confirmed, and in 1907 dengue was the second disease (after yellow fever) that was shown to be caused by a virus. Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the basic understanding of dengue transmission.

The marked spread of dengue during and after the Second World War has been attributed to ecologic disruption. The same trends also led to the spread of different serotypes of the disease to new areas and the emergence of dengue hemorrhagic fever. This severe form of the disease was first reported in the Philippines in 1953; by the 1970s, it had become a major cause of child mortality and had emerged in the Pacific and the Americas. Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome were first noted in Central and South America in 1981, as DENV-2 was contracted by people who had previously been infected with DENV-1 several years earlier.

Etymology

The name came into English in the early 19th century from West Indian Spanish, which borrowed it from the Kiswahili term dinga (in full kidingapopo, "disease caused by an evil spirit"). The term dengue fever came into general use only after 1828.

Treatment

Apart from the attempts to control the spread of the Aedes mosquito there are ongoing efforts to develop antiviral drugs that would be used to treat attacks of dengue fever and prevent severe complications. Discovery of the structure of the viral proteins may aid the development of effective drugs. Carica papaya leaf extract has been studied and has been used for treatment and in hospitals. As of 2020, studies have shown positive benefits on clinical blood parameters, but a beneficial effect on disease outcome has yet to be studied, and papaya leaf extract is not considered a standard of practice therapy.

In october 2021, the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium announced it has developed an antiviral in cooperation with Janssen Pharmaceutica, which can also be used to prevent the disease.

See also

In Spanish: Dengue para niños

In Spanish: Dengue para niños