Ce Acatl Topiltzin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ce Acatl Topiltzin |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Toltecs | |

|

|

| Reign | 923–947 |

| Predecessor | Xochitl |

| Successor | Matlacxochtli |

| Born | 895 Tepoztlán, Toltec Empire |

| Died | 947 Tlapallan, Gulf of Mexico |

| Father | Mixcōatl |

| Mother | Chimalman |

| Religion | Toltec religion |

Cē Ācatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl [sɛː ɑːkatɬ toˈpilt͡sin ketsalˈkoatɬ] (Our Prince One-Reed Precious Serpent) (c. 895–947) is a mythologised figure appearing in 16th-century accounts of Nahua historical traditions, where he is identified as a ruler in the 10th century of the Toltecs— by Aztec tradition their predecessors who had political control of the Valley of Mexico and surrounding region several centuries before the Aztecs themselves settled there.

In later generations, he was a figure of legend often confused or conflated with the important Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl. According to legend in El Salvador, the city of Cuzcatlán (the capital city of the Pipil/Cuzcatlecs) was founded by the exiled Toltec Ce Acatl Topiltzin.

Contents

Story

Topiltzin Cē Ācatl Quetzalcōatl was the Lord of the Toltecs and their major city Tōllan.

One version of the story is that he was born in the 10th century, during the year and day-sign "1 Acatl," correlated to date May 13 of the year 895, allegedly in what is now the town of Tepoztlán. According to various sources, he had four different possible fathers, the most popular of which is Mixcōatl ("Cloud Serpent"), the god of war, fire, and the hunt, and presumably also an earlier Toltec king—Mesoamerican leaders and high-priests sometimes took the names of the deity who was their patron. His mother is at times unnamed, but Chimalman is the most accepted.

There exist few accounts of Ce Acatl's early childhood. However, all information agrees that he proved his worth first as a warrior and then as a priest to the people of Tollan.

He assumed lordship over the Toltecs and migrated his people to Tollan. Reigning in peace and prosperity he contributed much to the lifestyle of the Toltecs with basic ideas such as civilization. He was generally considered a god upon earth by his followers with similar powers to those of his namesake. According to legend, the most accepted fate of the man-god was that during the year "1 Acatl" or 947, and at the age of 53 he migrated to the Gulf coast Tlapallan where he took a canoe and burned himself.

He dispelled the traditions of the past and ended all human sacrifice during his reign. The translations claim that he loved his people so much he insisted that they only meet the ancient standards of the gods; he had the Toltec offer them snakes, birds and other animals, but not humans, as sacrifices. To prove his penance, to atone for the earlier sins of his people, and to appease the debt owed to the gods (created by lack of tribute of human blood) he also created the cult of the serpent. This cult insisted that the practitioners bleed themselves to satiate the needs of the netherworld. It also demanded that all priests remain celibate and did not allow intoxication of any kind (representing the two major sins to which the original 400 Mixcohua succumbed). These edicts and his personal purity of spirit caused Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl to be beloved by his vassals and revered for generations. The representation of the priestly ruler became so important that subsequent rulers would claim direct descent from Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl in order to legitimize their monarchies.

Once he left Tollan, the name was used by other elite figures to keep a line of succession and was also used by the Mexica to more easily rule over the Toltecs.

According to the Florentine Codex, which was written under the direction of the Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún, the Aztecs had a legend that Quetzalcoatl would one day return, and Emperor Moctezuma II mistook Hernán Cortés for Quetzalcoatl. Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans believed the conquerors to be gods: most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Geronimo Mendieta (Martínez 1980). Some Franciscans at this time held millennarian beliefs (Phelan 1956), and the natives taking the Spanish conquerors for gods was an idea that went well with this theology.

Some scholars still hold the view that the fall of the Aztec empire can in part be attributed to Moctezuma's belief in Cortés as the returning Quetzalcoatl, but most modern scholars see the "Quetzalcoatl/Cortés myth" as one of many myths about the Spanish conquest which originated in the early post-conquest period.

Topiltzin's legacy

The tales end with Topiltzin traveling across Mesoamerica founding small communities and giving all the features their respective names. The Aztecs believed that Topiltzin's search for his holy resting place eventually led him across the sea to the east, from whence he vowed to return one day and reclaim Cholula (Chimalpahin, Motolinia, Ixtlilxochitl, Codice Rios). Other sources insist that Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl would not return but that he would send representatives to warn or possibly pass judgment on those inhabiting the land (Las Casas, Mendieta, Veytia). Aztec rulers used the myth of the great founder of Tollan to help legitimize their claims to seats of power. They claimed that, as the direct descendants of the Priest-King, they had the right and duty to hold his place until the day Topiltzin would return. The myths would prove to have a lasting effect on the Aztec empire. They rationalized the mass sacrifices that were already destabilizing the empire when the first Spaniards arrived. The stories of Topiltzin further expedited the collapse of the Aztec nation by sheer coincidence; they bore incredible likeness to the arrival of the first Spaniards. The Aztec may have truly believed that they were seeing the return of the famous priest when the white-haired Hernán Cortés landed on their shores in 1519. He came from across the sea to the east, wearing brilliant armor (as the deity Quetzalcoatl is oft depicted) accompanied by four men (possibly believed to be the other four progenitors of the Mesoamerican people that survived the massacre before coming to earth or Topiltzin’s messengers). The Spanish arrival terrified the ruling class. They feared they would be exposed as frauds and, at the very least, lose their ruling status to Topiltzin. Conversely the oppressed Aztec people, taxed and forced to wage war for sacrifices, hoped that these arrivals would bring a new era of peace and enlightenment (Carrasco 2000:145-152). Ultimately the Aztecs' rulers still lost their status and the Aztec people were not freed from oppression.

As the Spanish conquered Mesoamerica they destroyed countless works concerning and pre-dating the Aztecs. The story of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl was almost destroyed as the conquistadors forced the few remaining traces into hiding. Only relatively recently have accurate translations of much of the information about Topiltzin been made available. Unfortunately, even the comparatively complete accounts are but a portion of the story. Much of the information varies from region to region and has changed through the course of time (as myths are apt to do).

Regalia

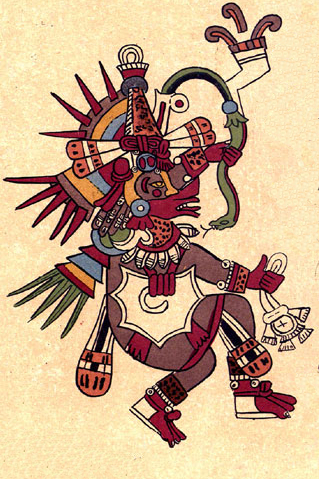

Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl is usually seen with a plumed headpiece, a curved baton (the chicoacolli) and a feather rimmed shield with the ehecacozcatl (wind jewel) emblem on it.

See also

In Spanish: Ce Ácatl Topiltzin Quetzalcóatl para niños

In Spanish: Ce Ácatl Topiltzin Quetzalcóatl para niños

- List of people from Morelos, Mexico