Burning of Washington facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Burning of Washington |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

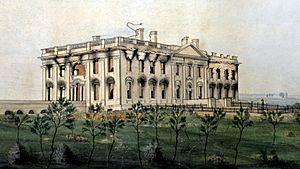

Burning of Washington, Paul de Thoyras |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,250 | 7,640 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 30 killed 6 wounded |

Unknown killed and wounded 1 frigate destroyed 1 frigate scuttled 1 sloop scuttled |

||||||

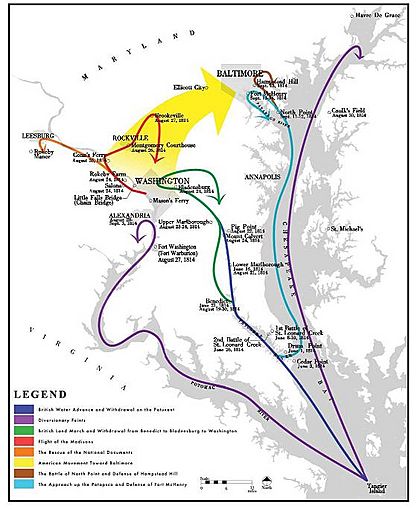

The Burning of Washington was a British invasion of Washington City (now Washington, D.C.), the capital of the United States, during the Chesapeake Campaign of the War of 1812. It is the only time since the American Revolutionary War that a foreign power has captured and occupied the capital of the United States.

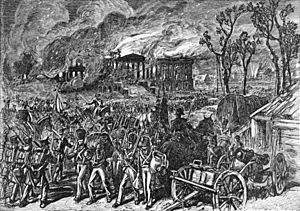

Following the defeat of American forces at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814, a British force led by Major General Robert Ross marched to Washington. That night, British forces set fire to multiple government and military buildings, including the White House (then called the Presidential Mansion), the Capitol building, as well as other facilities of the U.S. government. The attack was in part a retaliation for American destruction in Upper Canada: U.S. forces had burned and looted its capital the previous year and then had burned buildings in Port Dover. Less than a day after the attack began, a heavy thunderstorm—possibly a hurricane—and a tornado extinguished the fires. The occupation of Washington lasted for roughly 26 hours.

President James Madison, military officials, and his government evacuated and were able to find refuge for the night in Brookeville, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland; President Madison spent the night in the house of Caleb Bentley, a Quaker who lived and worked in Brookeville. Bentley's house, known today as the Madison House, still exists. Following the storm, the British returned to their ships, many of which required repairs due to the storm.

Contents

Reasons

The United Kingdom was already at war with Napoleonic France when the Americans declared war in 1812. The war against France took up most of Britain's attention and military resources. The initial British strategy against the United States focused on imposing a partial blockade at sea, and maintaining a defensive stance on land. Reinforcements were held back from Canada and reliance was instead made on local militias and native allies to bolster the British Army in Canada. However, with the defeat and exile of Napoleon Bonaparte in April 1814, Britain was able to use its now available troops and ships to prosecute its war with the United States. The Earl of Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, dispatched an army brigade and additional naval vessels to the Imperial fortress of Bermuda, from where a blockade of the US coast and even the occupation of some coastal islands had been overseen throughout the war. It was decided to use these forces in raids along the Atlantic seaboard to draw American forces away from Canada.

The commanders were under strict orders, however, not to carry out operations far inland, or to attempt to hold territory. Early in 1814, Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy's North America and West Indies Station, controlling naval forces based at the new Bermuda dockyard and the Halifax Naval Yard which were used to blockade US Atlantic ports throughout the war. He planned to carry the war into the United States by attacks in Virginia and against New Orleans.

Rear Admiral George Cockburn had commanded the squadron in Chesapeake Bay since the previous year. On June 25, he wrote to Cochrane stressing that the defenses there were weak, and he felt that several major cities were vulnerable to attack. Cochrane suggested attacking Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia. Rear Admiral Cockburn accurately predicted that "within a short period of time, with enough force, we could easily have at our mercy the capital". He had recommended Washington as the target, because of the comparative ease of attacking the national capital and "the greater political effect likely to result". Major General Ross was less optimistic. He "never dreamt for one minute that an army of 3,500 men with 1,000 marines reinforcement, with no cavalry, hardly any artillery, could march 50 miles inland and capture an enemy capital", according to CBC News. Ross also refused to accept Cockburn's recommendation to burn the entire city. He spared nearly all of the privately owned properties.

Major General Ross commanded the 4,500-man army in Washington, composed of the 4th (King's Own) Regiment of Foot, 21st (Royal North British Fusilier) Regiment of Foot, 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot, and 85th Regiment of Foot.

An added motive was retaliation for what Britain saw as the "wanton destruction of private property along the north shores of Lake Erie" by American forces under Col. John Campbell in May, the most notable being the Raid on Port Dover. On June 2, Sir George Prévost, Governor General of British North America wrote to Cochrane at Admiralty House, in Bailey's Bay, Bermuda, calling for a retaliation against the American destruction of private property in violation of the laws of war. Prévost argued that,

in consequence of the late disgraceful conduct of the American troops in the wanton destruction of private property on the north shores of Lake Erie, in order that if the war with the United States continues you may, should you judge it advisable, assist in inflicting that measure of retaliation which shall deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages.

Many sources also suggest that the attack on Washington was motivated by revenge for the looting of York in Upper Canada, the provincial capital, after the Battle of York in April 1813. Research completed by The Washington Post, however rebuts that claim. "The earlier arson of parliament buildings in York was not raised as a justification until months later, after the British faced criticism at home and abroad for burning buildings in Washington". Earlier, the British had filed complaints only about the "wanton destruction" along the Niagara region and Lake Erie.

On July 18, Cochrane ordered Cockburn to "deter the enemy from a repetition of similar outrages ... You are hereby required and directed to destroy and lay waste such towns and districts as you may find assailable". Cochrane instructed, "You will spare merely the lives of the unarmed inhabitants of the United States". Ross and Cockburn surveyed the torching of the President's Mansion, during which time a great storm arose unexpectedly out of the southeast. They were confronted a number of times while on horseback by older women from around Washington City and elderly clergymen (Southern Presbyterian and Southern Baptist), with women and children who had been hiding in homes and churches. They requested protection from abuse and robbery by enlisted personnel from the British Expeditionary Forces whom they accused of having tried to ransack private homes and other buildings. Major-General Ross had two British soldiers put in chains for violation of his general order. Throughout the events of that day, a severe storm blew into the city, worsening on the night of August 24, 1814.

Events

President James Madison, members of his government, and the military fled the city in the wake of the British victory at the Battle of Bladensburg. They found refuge for the night in Brookeville, a small town in Montgomery County, Maryland, which is known today as the "United States' Capital for a Day." President Madison spent the night in the house of Caleb Bentley, a Quaker who lived and worked as a silversmith in Brookeville. Bentley's house, known today as the Madison House, still stands in Brookeville.

The sappers and miners of the Corps of Royal Engineers under Captain Blanshard were employed in burning the principal buildings. Blanshard reported that it seemed that the American President was so sure that the attacking force would be made prisoners that a handsome entertainment had been prepared. Blanshard and his sappers enjoyed the feast.

On August 24, 1814, British troops led by Major General Robert Ross, accompanied by Rear Admiral George Cockburn, attacked the capital city with a force of 4,500 "battle hardened" men. The plan to attack Washington had been formulated by Rear Admiral Cockburn, who predicted that "within a short period of time, with enough force, we could easily have at our mercy the capital". Major General Ross commanded the troops, and was less optimistic. While Cockburn recommended burning the entire city, Ross planned to damage only public buildings.

U.S. Capitol

The Capitol was, according to some contemporary travelers, the only building in Washington "worthy to be noticed". Thus, it was a prime target for the British, for both its aesthetic and its symbolic value. Upon arrival into the city via Maryland Avenue, the British targeted the Capitol (first the southern wing, containing the House of Representatives, then the northern wing, containing the Senate). Prior to setting it aflame, the British sacked the building (which at that time housed Congress, the Library of Congress, and the Supreme Court).

Items looted by troops led by Rear-Admiral Cockburn included a ledger entitled "An account of the receipts and expenditures of the United States for the year 1810"; the admiral wrote on the inside leaf that it was "taken in President's room in the Capitol, at the destruction of that building by the British, on the capture of Washington, 24th August, 1814". He later gave it to his elder brother Sir James Cockburn, the Governor of Bermuda. The book was returned to the Library of Congress in 1940.

The British intended to burn the building to the ground. They set fire to the southern wing first. The flames grew so quickly that the British were prevented from collecting enough wood to burn the stone walls completely. However, the Library of Congress's contents in the northern wing contributed to the flames on that side. Among the items destroyed was the 3,000-volume collection of the Library of Congress and the intricate decorations of the neoclassical columns, pediments, and sculptures designed by William Thornton in 1793 and Benjamin Latrobe in 1803. The wooden ceilings and floors burned, and the glass skylights melted because of the intense heat. The building was not a complete loss; the House rotunda, the east lobby, the staircases, and Latrobe's famous Corn-Cob Columns in the Senate entrance hall all survived. The Superintendent of the Public Buildings of the City of Washington, Thomas Munroe, concluded that the loss to the Capitol amounted to $787,163.28, with $457,388.36 for the North wing and main building, and $329,774.92 for the South wing.

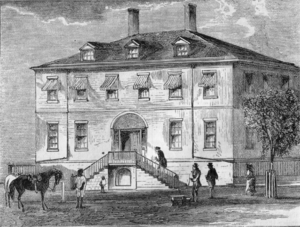

White House

After burning the Capitol, the British turned northwest up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. After US government officials and President Madison fled the city, the First Lady Dolley Madison received a letter from her husband, urging her to be prepared to leave Washington at a moment's notice. Dolley organized the enslaved and other staff to save valuables from the British. James Madison's personal enslaved attendant, the fifteen-year-old boy Paul Jennings, was an eyewitness. After later buying his freedom from the widow Dolley Madison, Jennings published his memoir in 1865, considered the first from the White House:

It has often been stated in print, that when Mrs. Madison escaped from the White House, she cut out from the frame the large portrait of Washington (now in one of the parlors there), and carried it off. She had no time for doing it. It would have required a ladder to get it down. All she carried off was the silver in her reticule, as the British were thought to be but a few squares off, and were expected any moment.

Jennings said the people who saved the painting and removed the objects actually were:

John Susé (Jean Pierre Sioussat, the French door-keeper, and still living at the time of Jennings's memoir) and Magraw [McGraw], the President's gardener, took it down and sent it off on a wagon, with some large silver urns and such other valuables as could be hastily got hold of. When the British did arrive, they ate up the very dinner, and drank the wines, &c., that I had prepared for the President's party.

The soldiers burned the president's house, and fuel was added to the fires that night to ensure they would continue burning into the next day.

In 2009, President Barack Obama held a ceremony at the White House to honor Jennings as a representative of his contributions to saving the Gilbert Stuart painting and other valuables. (The painting that was saved was a copy Stuart made of the painting, not the original, although it is the same one on display in the East Room.) "A dozen descendants of Jennings came to Washington, to visit the White House. They looked at the painting their relative helped save." In an interview with National Public Radio, Jennings' great-great-grandson, Hugh Alexander, said, "We were able to take a family portrait in front of the painting, which was for me one of the high points." He confirmed that Jennings later purchased his freedom from the widowed Dolley Madison.

Other Washington properties

The day after the destruction of the White House, Rear Admiral Cockburn entered the building of the D.C. newspaper, the National Intelligencer, intending to burn it down. However, several women persuaded him not to because they were afraid the fire would spread to their neighboring houses. Cockburn wanted to destroy the newspaper because its reporters had written so negatively about him, branding him "The Ruffian". Instead, he ordered his troops to tear the building down brick by brick, and ordered all the "C" type destroyed "so that the rascals can have no further means of abusing my name".

The British sought out the United States Treasury in hopes of finding money or items of worth, but they found only old records. They burned the United States Treasury and other public buildings. The United States Department of War building was also burned. However, the War and State Department files had been removed, so the books and records had been saved; the only records of the War Department lost were recommendations of appointments for the Army and letters received from seven years earlier.

The First U.S. Patent Office Building was saved by the efforts of William Thornton, the former Architect of the Capitol and then the Superintendent of Patents, who gained British cooperation to preserve it. "When the smoke cleared from the dreadful attack, the Patent Office was the only Government building ... left untouched" in Washington.

The Americans had already burned much of the historic Washington Navy Yard, founded by Thomas Jefferson, to prevent capture of stores and ammunition, as well as the 44-gun frigate USS Columbia and the 22-gun USS Argus, both new vessels nearing completion. The Navy Yard's Latrobe Gate, Quarters A, and Quarters B were the only buildings to escape destruction. Also spared were the Marine Barracks and Commandant's House, although several private properties were damaged or destroyed.

In the afternoon of August 25, General Ross sent two hundred men to secure a fort on Greenleaf's Point. The fort, later known as Fort McNair, had already been destroyed by the Americans, but 150 barrels of gunpowder remained. While the British were trying to destroy it by dropping the barrels into a well, the powder ignited. As many as thirty men were killed in the explosion, and many others were maimed.

"The Storm that Saved Washington"

Less than four days after the attack began, a sudden, very heavy thunderstorm—possibly a hurricane—put out the fires. It also spun off a tornado that passed through the center of the capital, setting down on Constitution Avenue and lifting two cannons before dropping them several yards away and killing British troops and American civilians alike. Following the storm, the British troops returned to their ships, many of which were badly damaged. There is some debate regarding the effect of this storm on the occupation. While some assert that the storm forced their retreat, it seems likely from their destructive and arsonous actions before the storm, and their written orders from Cochrane to "destroy and lay waste", that their intention was merely to raze the city, rather than occupy it for an extended period. It is also clear that commander Robert Ross never intended to damage private buildings as had been recommended by Cockburn and Alexander Cochrane.

Whatever the case, the British occupation of Washington lasted only about 26 hours. Despite this, the "Storm that saved Washington", as it became known, did the opposite according to some. The rains sizzled and cracked the already charred walls of the White House and ripped away at structures the British had no plans to destroy (such as the Patent Office). The storm may have exacerbated an already dire situation for Washington D.C.

An encounter was noted between Sir George Cockburn and a female resident of Washington. "Dear God! Is this the weather to which you are accustomed in this infernal country?" enquired the Admiral. "This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city", the woman allegedly called out to Cockburn. "Not so, Madam", Cockburn retorted. "It is rather to aid your enemies in the destruction of your city", before riding off on horseback.

The Royal Navy reported that it lost one man killed and six wounded in the attack, of whom the fatality and three of the wounded were from the Corps of Colonial Marines.

The destruction of the Capitol, including the Senate House and the House of Representatives, the Arsenal, Dockyard, Treasury, War Office, President's mansion, bridge over the Potomac, a frigate and a sloop together with all materiel was estimated at £365,000 or around $40,540,000 in 2021.

A separate British force captured Alexandria, Virginia, on the south side of the Potomac River, while Ross's troops were leaving Washington. The mayor of Alexandria made a deal and the British refrained from burning the town.

In 2013, an episode of the Weather Channel documentary series When Weather Changed History, entitled "The Thunderstorm That Saved D.C.", was devoted to these events.

Aftermath

President Madison and the military officers returned to Washington by September 1, on which date Madison issued a proclamation calling on citizens to defend the District of Columbia. Congress did not return for three and a half weeks. When they did so, they assembled in special session on September 19 in the Post and Patent Office building at Blodgett's Hotel, one of the few buildings large enough to hold all members to be spared. Congress met in this building until December 1815, when construction of the Old Brick Capitol was complete.

Most contemporary American observers, including newspapers representing anti-war Federalists, condemned the destruction of the public buildings as needless vandalism. Many in the British public were shocked by the burning of the Capitol and other buildings at Washington; such actions were denounced by most leaders of continental Europe, where capital cities had been repeatedly occupied in the course of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars but always spared destruction (at least on the part of the occupiers – the famous burning of Moscow that occurred less than two years prior had been an act carried out by the defenders). According to The Annual Register, the burning had "brought a heavy censure on the British character", with some members of Parliament, including the anti-establishment MP Samuel Whitbread, joining in the criticism, declaring that the government was making much of the taking of a few buildings in a non-strategic swamp, as though it had captured Paris.

The majority of British opinion imagined that the burnings were justified following the damage that United States forces had done with its incursions into Canada. In addition, they claimed that the United States had been the aggressor, declaring war and initiating it (this view did not regard American complaints about the kidnapping of American seamen). Several commentators regarded the damages as just revenge for the American destruction of the Parliament buildings and other public buildings in York, the provincial capital of Upper Canada, early in 1813. Sir George Prévost wrote that "as a just retribution, the proud capital at Washington has experienced a similar fate". The Reverend John Strachan, who as Rector of York had witnessed the American acts there, wrote to Thomas Jefferson that the damage to Washington "was a small retaliation after redress had been refused for burnings and depredations, not only of public but private property, committed by them in Canada".

When they ultimately returned to Bermuda, the British forces took with them two pairs of portraits of King George III and his wife, Queen Charlotte, which had been discovered in one of the public buildings. One pair currently hangs in the House of Assembly of the Parliament of Bermuda, and the other in the Cabinet Building, both in the city of Hamilton.

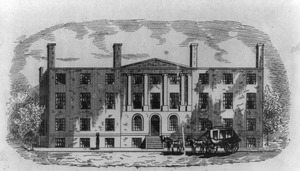

Reconstruction

There was a movement in Congress to relocate the capital after the burning. Congressmen from the North pushed for relocation to Philadelphia or some other prominent northern city, while Southern congressmen claimed that moving the capital would degrade the American sense of dignity and strength (however, many Southern congressmen simply did not want to move the capital north of the Mason–Dixon line). On September 21, the House of Representatives voted to strike down a proposal to relocate the capital from Washington, D.C. by a margin of 83 to 54.

On February 3, 1815, in an effort to guarantee that the federal government would always remain in the area, Washington property owners funded the building of the Old Brick Capitol, a larger meeting space where the Supreme Court now stands. Construction of the Old Brick Capitol cost $25,000 and was funded primarily through the sale of stocks. The largest donor was Daniel Carroll of Duddington, a rich English property owner in the area. Construction began on July 4, and concluded in December. Congress met in the Old Brick Capitol between December 1815 and December 1819, when the Capitol reopened.

The Capitol reconstruction took much longer than anticipated. The Old Brick Capitol took only five months to complete, but the Capitol took twelve years. A committee appointed by Congress to investigate the damage to the District concluded that it was cheaper to rebuild the already existing and damaged buildings than to build an entirely new one. On February 13, President Madison and Congress passed legislation to borrow $500,000 to repair the public buildings, including the Capitol, "on their present sites in the city of Washington". Benjamin Latrobe, architect of the Capitol who took over for William Thornton in 1803, was rehired to repair the building on April 18. He immediately requested 60,000 feet (18,288 m) of boards, 500 tons of stone, 1,000 barrels of lime, and brick.

With the $500,000 borrowed from Washington banks, Latrobe was able to rebuild the two wings and the central dome before being fired in 1817 over budgetary conflicts. Charles Bulfinch took over and completed the renovations by 1826. Bulfinch modified Latrobe's design by increasing the height of the Capitol dome to match the diameter of 86 ft (26,2 m). With the reconstruction of the public buildings in Washington, the value of land in the area increased dramatically, paving the way for the expansion of the city that developed in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

In Literature

Lydia Sigourney reflects on this event in her poem ![]() The Conflagration at Washington., written under her maiden name, Lydia Huntley, in her first collection of poetry of 1815.

The Conflagration at Washington., written under her maiden name, Lydia Huntley, in her first collection of poetry of 1815.

See also

In Spanish: Quema de Washington para niños

In Spanish: Quema de Washington para niños