Bose–Einstein condensate facts for kids

In condensed matter physics, a Bose–Einstein condensate (BEC) is a state of matter that is formed by cooling a gas of extremely low density (about 100,000 times less dense than normal air) to ultra-low temperatures that are very close to absolute zero (−273.15 °C or −459.67 °F). In this state of matter, separate atoms or subatomic particles clump together and act as a single atom. It can then almost be seen by the naked eye.

This state was first officially predicted in 1924–1925 by Albert Einstein after Satyendra Nath Bose showed him the idea in the new field now known as quantum statistics. Einstein gave Bose credit for the idea.

History

Bose sent a paper on the quantum statistics of light quanta (now called photons) to Einstien. Einstein was impressed with the paper. He translated it to German and submitted it for Bose to the Zeitschrift für Physik, a scientific journal. They published it in 1924.

Einstein wrote two more papers using Bose's ideas. He took the ideas that used quantum statistics and used them to see if it would be possible to change gas molecules. The idea of a Bose gas was the result. Bosons are particles that carry energy and forces and follow the rules of Bose-Einstein statistics. Einstein suggested that cooling bosonic atoms to a very low temperature would cause them to fall (or "condense") into the lowest accessible quantum state, resulting in a new form of matter.

After two program directors at the National Science Foundation (William Stwalley and Lewis Nosanow) published a paper about making a Bose–Einstein condensate in the laboratory, four research groups tried the idea. These groups were led by Isaac Silvera (University of Amsterdam), Walter Hardy (University of British Columbia), Thomas Greytak (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), and David Lee (Cornell University).

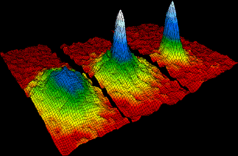

On June 5, 1995, the first gaseous condensate was produced by Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman at the University of Colorado at Boulder NIST–JILA lab. They made it in a gas of rubidium atoms cooled to 170 nanokelvins (nK). Shortly thereafter, Wolfgang Ketterle at MIT produced a Bose–Einstein Condensate in a gas of sodium atoms. For their accomplishments, Cornell, Wieman, and Ketterle received the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics. These early studies founded the field of ultracold atoms. Hundreds of research groups around the world now make BECs in their labs. Scientists are still researching this idea.

Derivation

To get Bose–Einstein condensate, gas must be cooled to extremely low temperatures. The first step is to cool atoms with a laser beam. This makes them almost stop moving. The next step is to "catch" the atoms in a magnetic bowl-shaped area. Using these techniques, Cornell and Wieman combined about 2,000 atoms into one "superatom" that was large enough to observe with a microscope. This "superatom" had distinct quantum properties.

Bose–Einstein condensates are incredibly fragile. The slightest temperature change would be enough to change them to a normal gas.

Current research

In 1970, BECs were proposed by Emmanuel David Tannenbaum for anti-stealth technology.

BEC research has caused new ideas, such as the atom laser. While a traditional laser casts a beam of photons, the atom laser produces a beam of atoms that can be focused at high intensity. This laser can be more accurate.

BECs have proved to slow down light. Lene Hau of Harvard University and her colleagues managed to completely stop and store a light pulse within a BEC, later releasing the light unchanged or sending it to a second BEC. This property could be used for developing new types of light-based telecommunications, optical storage of data, and quantum computing.

Bose–Einstein condensates formed of a wide range of isotopes have been made. Researchers in the new field of atomtronics use the properties of Bose–Einstein condensates in the new quantum technology of matter-wave circuits.

In 2020, researchers reported the development of superconducting BEC.

Images for kids

-

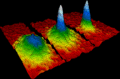

Velocity-distribution data (3 views) for a gas of rubidium atoms, confirming the discovery of a new phase of matter, the Bose–Einstein condensate. Left: just before the appearance of a Bose–Einstein condensate. Center: just after the appearance of the condensate. Right: after further evaporation, leaving a sample of nearly pure condensate.

See also

In Spanish: Condensado de Bose-Einstein para niños

In Spanish: Condensado de Bose-Einstein para niños