Alexander D. Shimkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Demitri Shimkin

|

|

|---|---|

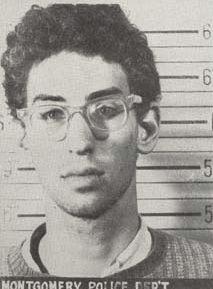

Alexander Shimkin after he was arrested for civil rights activity in Alabama in 1965

|

|

| Born | October 11, 1944 Washington, D.C.

|

| Died | July 12, 1972 (aged 27) Quảng Trị Province, Vietnam

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | war correspondent |

| Known for | investigating non-combatant casualties in Operation Speedy Express |

| Military career | |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War

|

Alexander Demitri "Alex" Shimkin (October 11, 1944 – July 12, 1972) was an American war correspondent who was killed in Vietnam. He is notable for his investigation of non-combatant casualties in Operation Speedy Express.

Contents

Early life and civil rights work

Born in Washington, D.C., Shimkin moved with his family in 1960 to Urbana, Illinois, where his parents, anthropologists Demitri B. Shimkin and Edith Manning Shimkin, had joined the faculty of the University of Illinois. Although he was baptized an Episcopalian, Shimkin and his family were members of a Methodist church in Urbana. Intensely interested in military history, he made notebooks listing the order of battle for World War I armies.

Shimkin graduated from Urbana High School in 1962, then attended the University of Michigan where he majored in history. He left college in 1965 and became an activist in the civil rights movement, first with the Northern Student Movement in Alabama, then with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). After the first of the Selma to Montgomery marches, on March 7, 1965, ended with violent attacks on the peaceful marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Shimkin traveled to Selma, arriving in time to join the March 9 "Turnaround Tuesday" march, led by Martin Luther King Jr. During the leadup and completion of the third, successful, march to Montgomery, Shimkin was arrested on March 18 and again on March 22.

In Mississippi, he was among 140 demonstrators arrested in Natchez on October 2, 1965, and detained three days at Parchman State Prison Farm, where he and others were kept in cold cells with no bedding. He wrote an eight-page "Natchez Political Handbook" outlining the local political structure and the right to demonstrate.

Shimkin was a full-time MFDP staff member in Quitman County in 1966. On June 9, 1966, he joined the March Against Fear organized by activist James Meredith who had been shot and injured a few days before. In Holmes County, he helped organize a Head Start program and a voter registration drive that registered over 6,000 African Americans for the 1967 election. Together with his father, Shimkin organized a project through which 18 African American students from Holmes County were selected to attend the University of Illinois. In a note that he left behind in Mississippi, Shimkin wrote, "Since I was barely twenty, I've devoted almost every moment of my life to the [civil rights] movement...."

Volunteer service in Vietnam and the Ba Chúc story

Returning to his studies, Shimkin graduated with "high distinction" in government from Indiana University (Bloomington) in 1969, then became a community development worker with International Voluntary Services (IVS) in Laos and South Vietnam. While with IVS in Vietnam, Shimkin and another volunteer, Ronald Moreau, became sources for a New York Times story by Gloria Emerson published in January 1971 about the forced use of Vietnamese civilians by South Vietnamese officers and their American advisers to clear land mines near the village of Ba Chúc on the Cambodian border. As Moreau later described the situation, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers planted mines on hillsides near the village to protect their upland positions and successfully resisted combined American and South Vietnamese air and ground attacks. Believing that the villagers knew where the communist forces had placed the mines and booby traps, the American and South Vietnamese officers forced the Ba Chúc villagers at gunpoint to use hand tools to locate and remove the mines, a task that resulted in several deaths and serious injuries among the villagers when the explosives detonated. There were also casualties from mortar attacks by the communists who wanted to disrupt the operation.

After contacting Emerson, Shimkin and Moreau went with her to interview the villagers. According to Moreau, Emerson's story "had an immediate impact", causing the Pentagon to order an immediate halt to the mine-clearing operation. The story also brought a halt to Shimkin's and Moreau's service with IVS, which fired them for speaking to the press without permission. According to Moreau, Emerson intervened again, getting Shimkin a job as a stringer with Newsweek and Moreau one with The Washington Post.

Investigation of Operation Speedy Express

Working for Newsweek, Shimkin read documents released by the United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). Reviewing the MACV (pronounced "mack vee") documents about Operation Speedy Express, conducted in the Mekong Delta from December 1968 through May 1969, Shimkin noticed the large disparity between the American claims of 10,899 enemy dead and the reported capture of only 748 enemy weapons. Shimkin's conclusion, based on further documentary research and on interviews with American officials and Vietnamese witnesses, was that a large number of the reported dead were unarmed Vietnamese non-combatants whose deaths, whether accidental or deliberate, were used to enhance the body count that commanders of the Ninth Infantry Division considered the measure of the operation's success. Among the specific incidents uncovered by Shimkin was the one at Thanh Phong on the night of February 25–26, 1969, in which United States Navy SEALs led by Lieutenant (jg) Bob Kerrey, later Governor of Nebraska and a United States Senator, killed 21 civilians who were added to the body count of enemy dead, information that did not become public until 2001.

Shimkin and his boss, Newsweek's Saigon bureau chief Kevin P. Buckley, produced a 4,700-word story that specifically alleged "that thousands of Vietnamese civilians have been killed deliberately by U.S. forces." The numbers, if not the deliberate nature of the casualties, were later supported by an official, though secret, U.S. Army report that concluded: "[W]hile there appears to be no means of determining the precise number of civilian casualties incurred by US forces during Operation Speedy Express, it would appear that the extent of these casualties was in fact substantial, and that a fairly solid case can be constructed to show that civilian casualties may have amounted to several thousand (between 5,000 and 7,000)."

Pared back to 1,800 words by Newsweek editors who feared that the allegations would be seen as a "gratuitous attack" on the administration of President Richard M. Nixon following the revelations of the My Lai Massacre, the story was published in the June 19, 1972, issue under the title "Pacification's Deadly Price", but it attracted little attention. A few weeks later, Shimkin was killed.

Shimkin at Trảng Bàng

On June 8, 1972, a month before he died, Shimkin was one of the journalists present at Trảng Bàng in Tây Ninh Province when photographer Nick Ut captured his famous image of the nine-year-old Vietnamese girl Phan Thị Kim Phúc and some other children fleeing a napalm attack. Two South Vietnamese Skyraider aircraft went off course and dropped the incendiary bombs near the journalists, resulting in the deaths of two children and inflicting serious burns on others, including Kim Phúc.

"Jesus! People have been bombed!" Shimkin is reported to have shouted. A picture taken by David Burnett from behind Kim Phúc shows a running man with his right arm outstretched toward her. Author Denise Chong has written that the man in the picture might be Shimkin. A few minutes later Shimkin was on his knees weeping and telling others,"Leave me alone."

Rescue on Route 13

While covering fighting north of Saigon on National Route 13 (the highway to An Lộc) during the first week of July 1972, Shimkin went to the aid of a wounded South Vietnamese soldier and carried him to safety under heavy mortar fire. The rescue was captured in a photograph that appeared July 7 in a Saigon newspaper. The picture later appeared in Newsweek.

Death

On July 12, 1972, Shimkin and another reporter, Charles "Chad" Huntley, became lost in Quảng Trị Province while covering Allied operations to expel North Vietnamese forces that had occupied the area in the Easter Offensive. Leaving behind their Jeep, they walked into a hand grenade attack by North Vietnamese soldiers. Fluent in Vietnamese, Shimkin attempted to communicate with the attackers, but was killed. "The last time I saw him he was standing straight up with his arms stretched out with a grenade lying about two feet from his feet", Huntley said. "He looked down once, looked back up and kept trying to explain. An explosion occurred, he started to crumple...."

A veteran of the U.S. Special Forces, Huntley was only slightly wounded and attributed his survival and escape to his military training. After seeing Shimkin fall he counted "about 10 rounds" of Allied artillery fire that "blew away everything in the area." Shimkin's body was not recovered, and he was classified "missing in action" by the Department of Defense. Former war correspondent Zalin Grant thought he had Shimkin's grave "fairly well pinpointed" in 2002, but as of 2018 Shimkin's remains had not been located. An interview with Chad Huntley about the attack that apparently killed Shimkin is archived at the Library of Congress as part of the Vietnam-Era Prisoner-Of-War/Missing-In-Action Database.

Personal interests

Shimkin told an oral history interviewer in 1965 that a college course in classical literature had given him "a certain philosophical perspective." According to information from Shimkin's IVS application, he liked the novels of William Faulkner and Theodore Dreiser as well as reading political science and American history. At the time of his death he had been accepted for graduate study at Princeton University and hoped to write the "definitive history" of the Vietnam War. Shimkin's interest in military history led him to donate books on the subject to the Indiana University Library. Shimkin also played rugby at Indiana.

Memorials

Over 70 books from Shimkin's military history collection are archived at the library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Shimkin is also commemorated in the Journalists Memorial at the Newseum in Washington, D.C. A memorial tree honoring Shimkin was planted in 2014 on the campus of Indiana University Bloomington. There is a cenotaph for him at The Homewood Cemetery in Pittsburgh, PA.

See also

- List of journalists killed and missing in the Vietnam War