Yanomami facts for kids

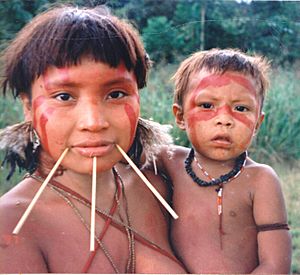

Yanomami woman and her child, June 1997

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approximately 35,339 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 16,069 (2009) | |

| 19,420 (2011) | |

| Languages | |

| Yanomaman languages | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism | |

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

Contents

Etymology

The ethnonym Yanomami was produced by anthropologists on the basis of the word yanõmami, which, in the expression yanõmami thëpë, signifies "human beings." This expression is opposed to the categories yaro (game animals) and yai (invisible or nameless beings), but also napë (enemy, stranger, non-Indian).

According to ethnologist Jacques Lizot:

Yanomami is the Indians' self-denomination ... the term refers to communities disseminated to the south of the Orinoco, [whereas] the variant Yanomawi is used to refer to communities north of the Orinoco. The term Sanumá corresponds to a dialect reserved for a cultural subgroup, much influenced by the neighboring Ye'kuana people. Other denominations applied to the Yanomami include Waika or Waica, Guiaca, Shiriana, Shirishana, Guaharibo or Guajaribo, Yanoama, Ninam, and Xamatari or Shamatari.

History

The first report of the Yanomami to the Northern world is from 1654, when an El Salvadorian expedition under Apolinar Diez de la Fuente visited some Ye'kuana people living on the Padamo River. Diez wrote:

By interlocution of an Uramanavi Indian, I asked Chief Yoni if he had navigated by the Orinoco to its headwaters; he replied yes, and that he had gone to make war against the Guaharibo [Yanomami] Indians, who were not very brave ... and who will not be friends with any kind of Indian.

From approximately 1630 to 1720, the other river-based indigenous societies who lived in the same region were wiped out or reduced as a result of slave-hunting expeditions by the conquistadors and bandeirantes. How this affected the Yanomami is unknown. Sustained contact with the outside world began in the 1950s with the arrival of members of the New Tribes Mission as well as Catholic missionaries from the Society of Jesus and Salesians of Don Bosco.

In Roraima, the 1970s saw the implementation of development projects within the framework of the "National Integration Plan" launched by the Brazilian military governments of the time. This meant the opening of a stretch of perimeter road (1973–76) and various colonization programs on land traditionally occupied by the Yanomami. During the same period, the Amazonian resources survey project RADAM (1975) detected important mineral deposits in the region. This triggered a progressive movement of gold prospectors, which after 1987 took the form of a real gold rush. Hundreds of clandestine runways were opened by gold miners in the major tributaries of the Branco River between 1987 and 1990. The number of gold miners in the Yanomami area of Roraima was then estimated at 30 to 40 thousand, about five times the indigenous population resident there.

Increasing pressure from farmers, cattle ranchers, and gold miners, as well as those interested in securing the Brazilian border by constructing roads and military bases near Yanomami communities, led to a campaign to defend the rights of the Yanomami to live in a protected area. In 1978 the Pro-Yanomami Commission (CCPY) was established. Originally named the Commission for the Creation of a Yanomami Park, it is a Brazilian non-governmental nonprofit organization dedicated to the defense of the territorial, cultural, and civil and political rights of the Yanomami. CCPY devoted itself to a long national and international campaign to inform and sensitize public opinion and put pressure on the Brazilian government to demarcate an area suited to the needs of the Yanomami. After 13 years the Yanomami indigenous land was officially demarcated in 1991 and approved and registered in 1992, thus ensuring that indigenous people had the constitutional right to the exclusive use of almost 96,650 square kilometres (37,320 sq mi) located in the States of Roraima and Amazonas.

The Alto Orinoco-Casiquiare Biosphere Reserve was created in 1993 with the objective of preserving the traditional territory and lifestyle of the Yanomami and Ye'kuana peoples. However, while the constitution of Venezuela recognizes indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral domains, few have received official title to their territories and the government has announced it will open up large parts of the Amazon rainforest to legal mining.

Organization

The Yanomami do not recognize themselves as a united group, but rather as individuals associated with their politically autonomous villages. Yanomami communities are grouped together because they have similar ages and kinship, and militaristic coalitions interweave communities together. The Yanomami have common historical ties to Carib speakers who resided near the Orinoco river and moved to the highlands of Brazil and Venezuela, the location the Yanomami currently occupy.

Mature men hold most political and religious authority. A tuxawa (headman) acts as the leader of each village, but no single leader presides over the whole of those classified as Yanomami. Headmen gain political power by demonstrating skill in settling disputes both within the village and with neighboring communities. A consensus of mature males is usually required for action that involves the community, but individuals are not required to take part. Local descent groups also play important roles in regulating marriages and settling disputes within villages.

Domestic life

Groups of Yanomami live in villages usually consisting of their children and extended families. Villages vary in size, but usually contain between 50 and 400 people. In this largely communal system, the entire village lives under a common roof called the shabono. Shabonos have a characteristic oval shape, with open grounds in the center measuring an average of 100 yards (91 m). The shabono shelter constitutes the perimeter of the village, if it has not been fortified with palisades.

Under the roof, divisions exist marked only by support posts, partitioning individual houses and spaces. Shabonos are built from raw materials from the surrounding rainforest, such as leaves, vines, and tree trunks. They are susceptible to heavy damage from rains, winds, and insect infestation. As a result, new shabonos are constructed every 4 to 6 years.

The Yanomami can be classified as foraging horticulturalists, depending heavily on rainforest resources; they use slash-and-burn horticulture, grow bananas, gather fruit, and hunt animals and fish. Crops compose up to 75% of the calories in the Yanomami diet. Protein is supplied by wild resources obtained through gathering, hunting, and fishing. When the soil becomes exhausted, Yanomami frequently move to avoid areas that have become overused, a practice known as shifting cultivation.

Children stay close to their mothers when young; most of the childrearing is done by women. Yanomami groups are a famous example of the approximately fifty documented societies that openly accept polyandry, though polygyny among Amazonian tribes has also been observed. Many unions are monogamous. Polygamous families consist of a large patrifocal family unit based on one man, and smaller matrifocal subfamilies: each woman's family unit, composed of the woman and her children. Life in the village is centered around the small, matrilocal family unit, whereas the larger patrilocal unit has more political importance beyond the village.

Males of the Yanomami are said to commit significant intervals of bride service living with their in-laws, and levirate or sororate marriage might be practiced in the event of the death of a spouse. Kin groups tend to be localized in villages and their genealogical depth is rather shallow. Kinship is critical in the arrangement of marriage and very strong bonds develop between kin groups who exchange women. Their kinship system can be described in terms of Iroquois classificatory pattern. To quote anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, “In a word, everyone in Yanomamo society is called by some kinship term that can be translated into what we would call blood relatives.”

The Yanomami are known as hunters, fishers, and horticulturists. The women cultivate cooking plantains and cassava in gardens as their main crops. Men do the heavy work of clearing areas of forest for the gardens. Another food source for the Yanomami is grubs. Often the Yanomami will cut down palms in order to facilitate the growth of grubs. The traditional Yanomami diet is very low in edible salt. Their blood pressure is characteristically among the lowest of any demographic group. For this reason, the Yanomami have been the subject of studies seeking to link hypertension to sodium consumption.

Rituals are a very important part of Yanomami culture. The Yanomami celebrate a good harvest with a big feast to which nearby villages are invited. The Yanomami village members gather large amounts of food, which helps to maintain good relations with their neighbors. They also decorate their bodies with feathers and flowers. During the feast, the Yanomami eat a lot, and the women dance and sing late into the night.

The women are responsible for many domestic duties and chores, excluding hunting and killing game for food. Although the women do not hunt, they do work in the gardens and gather fruits, tubers, nuts and other wild foodstuffs. The garden plots are sectioned off by family, and grow bananas, plantains, sugarcane, mangoes, sweet potatoes, papayas, cassava, maize, and other crops. Yanomami women cultivate until the gardens are no longer fertile, and then move their plots. Women are expected to carry 70 to 80 pounds (32 to 36 kg) of crops on their backs during harvesting, using bark straps and woven baskets.

In the mornings, while the men are off hunting, the women and young children go off in search of termite nests and other grubs, which will later be roasted at the family hearths. The women also pursue frogs, terrestrial crabs, or caterpillars, or even look for vines that can be woven into baskets. While some women gather these small sources of food, other women go off and fish for several hours during the day. The women also prepare cassava, shredding the roots and expressing the toxic juice, then roasting the flour to make flat cakes (known in Spanish as casabe), which they cook over a small pile of coals.

Yanomami women are expected to take responsibility for the children, who are expected to help their mothers with domestic chores from a very young age, and mothers rely very much on help from their daughters. Boys typically become the responsibility of the male members of the community after about age 8.

Using small strings of bark and roots, Yanomami women weave and decorate baskets. They use these baskets to carry plants, crops, and food to bring back to the shabono. They use a red berry known as onoto or urucu to dye the baskets, as well as to paint their bodies and dye their loin cloths. After the baskets are painted, they are further decorated with masticated charcoal pigment.

Why do the Yanomami adorn their bodies with sticks?

The Yanomami decorate their bodies with sticks for a number of reasons. One of them is to display their cultural heritage. They also do this to showcase their personal achievements and mark milestones in their life such as reaching adulthood or becoming a parent.

Threats

The Yanomami have been severely affected by gold mining, which has caused violence and serious health and social problems. From 1987 to 1990, the Yanomami population suffered from malaria, mercury poisoning, malnutrition, and violence due to an influx of garimpeiros searching for gold in their territory.

The Yanomami also face environmental threat due to deforestation caused by logging, road construction, and gold mining.

Language

Yanomaman languages comprise four main varieties: Ninam, Sanumá, Waiká, and Yanomamö. Many local variations and dialects also exist, such that people from different villages cannot always understand each other. Many linguists consider the Yanomaman family to be a language isolate, unrelated to other South American indigenous languages. The origins of the language are obscure.

Vocabulary

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for Yanomaman language varieties.

| gloss | Shirianá | Parimiteri | Sanemá | Pubmatari | Waica | Karime | Paucosa | Surára |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | kauitxamhét | chaamí | muliman | mahón | ||||

| two | tasíma | polakabí | botokaki | porakabö | ||||

| three | tasimaimhét | hiːriːpólagʔa | prukatabö | |||||

| head | bel-éhe | pil-héawan | pi-hé | pei-hé | pei-yáhe | ne-umgipe | peːiua-hé | |

| ear | beli-yaméke | pilmórokwiːn | pi-xinkawán | yímikek | pei-yameke | peːiua-niumekakeː | ||

| tooth | beli-uáke | pil-nákwan | pi-nakuán | pei-uák | pei-uáke | ne-parike | peːiua-uáke | |

| man | horóme | waro | wandzyé | wanodá | ũálõ | uáru | uau | uhanó |

| water | mãepe | madzyu | maduú | mãõ | mahu | maú | maú | |

| fire | oáke | kwárogʔe | kuadák | koawáke | oáke | uauká | kauːwaká | |

| stone | mamáke | muadamiːn | máma | mama | ||||

| sun | belipshí | pilmórokwiːn | pilmoró | motóka | motúka | mitukaki | peniboːínshi | |

| manioc | nazygóke | naasʔís | nashita | makóke | ||||

| jaguar | déhe | póleawan | poʔlé | íla | téhe | ührá |

Massacres

The Haximu massacre, also known as the Yanomami massacre, was an armed conflict in 1993, just outside Haximu, Brazil, close to the border with Venezuela. A group of garimpeiros killed approximately 16 Yanomami. In turn, Yanomami warriors killed at least two garimpeiros and wounded two more.

In July 2012 the government of Venezuela investigated another alleged massacre. According to the Yanomami, a village of eighty people was attacked by a helicopter and the only known survivors of the village were three men who happened to be out hunting while the attack occurred. However, in September 2012 Survival International, who had been supporting the Yanomami in this allegation, retracted their support after journalists could find no evidence to support the claim.

Groups working for the Yanomami

David Good, son of Yarima and her husband anthropologist Kenneth Good, created The Good Project to help support the future of the Yanomami people.

UK-based non-governmental organization Survival International has created global awareness-raising campaigns on the human rights situation of the Yanomami people.

In 1988 the US-based World Wildlife Fund (WWF) funded the musical Yanomamo, by Peter Rose and Anne Conlon, to convey what is happening to the people and their natural environment in the Amazon rainforest. It tells of Yanomami tribesmen/tribeswomen living in the Amazon and has been performed by many drama groups around the world.

The German-based non-governmental organization Yanomami-Hilfe e.V. is building medical stations and schools for the Yanomami in Venezuela and Brazil. Founder Rüdiger Nehberg crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1987 in a Pedalo and, together with Christina Haverkamp, in 1992 on a self-made bamboo raft in order to draw attention to the continuing oppression of the Yanomami people.

The Brazilian-based Yanomami formed their own indigenous organization Hutukara Associação Yanomami and accompanying website.

Comissão Pró-Yanomami (CCPY)

CCPY (formerly Comissão pela Criação do Parque Yanomami) is a Brazilian NGO focused on improving health care and education for the Yanomami. Established in 1978 by photographer Claudia Andujar, anthropologist Bruce Albert, and Catholic missionary Carlo Zacquini, CCPY has dedicated itself to the defense of Yanomami territorial rights and the preservation of Yanomami culture. CCPY launched an international campaign to publicize the destructive effects of the garimpeiro invasion and promoted a political movement to designate an area along the Brazil-Venezuela border as the Yanomami Indigenous Area. This campaign was ultimately successful.

Following demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Area in 1992, CCPY's health programs, in conjunction with the now-defunct NGO URIHI (Yanomami for "forest"), succeeded in reducing the incidence of malaria among the Brazilian Yanomami by educating Yanomami community health agents in how to diagnose and treat malaria. Between 1998 and 2001 the incidence of malaria among Brazilian Yanomami Indians dropped by 45%.

In 2000, CCPY sponsored a project to foster a market for Yanomami-grown fruit trees. This project aimed to help the Yanomami as they transition to an increasingly sedentary lifestyle because of environmental and political pressures. In a separate venture, the CCPY, per the request of Yanomami leaders, established Yanomami schools that teach Portuguese, aiming to aid the Yanomami in their navigation of Brazilian politics and international arenas in their struggle to defend land rights. Additionally, these village schools teach Yanomami about Brazilian society, including money use, good production, and record-keeping.

In popular culture

- Peter Rose and Anne Conlon, Yanomamo, a musical entertainment published by Josef Weinberger, London (1983)

- The 2008 Christian movie Yai Wanonabälewä: The Enemy God featured one of the Yanomami in the telling of the history and culture of his people.

- In the Sergio Bonelli comic book Mister No, the eponymous protagonist was once married to a Yanomami woman and often interacts with Yanomami (they are called "Yanoama" in the comic).

- In 1979, Chilean video artist Juan Downey released The Laughing Alligator, a 27-minute documentary of his two-months stay in the Amazon with the Yanomami.

- The Yanomami make a prominent appearance in the 2017 Bengali film, Amazon Obhijaan, aiding the protagonists in their search for the mythical city of El Dorado.

- Illusionist David Blaine featured the Yanomami in his 1997 television feature Magic Man.

See also

In Spanish: Pueblo yanomami para niños

In Spanish: Pueblo yanomami para niños