War in Sudan (2023) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids War in Sudan (2023) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

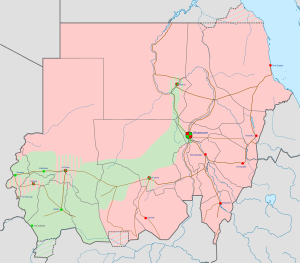

Military situation as of 12 February 2025 Controlled by Sudanese Armed Forces Controlled by Rapid Support Forces Controlled by SPLM-N (al-Hilu) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 110,000–120,000 Unknown |

70,000–150,000

Unknown |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 4,000–10,000 killed and 6,000–12,000 injured 4,118,119 internally displaced 1,130,516 refugees |

|||||||||

A war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), rival factions of the military government of Sudan, began on 15 April 2023, with the fighting concentrated around the capital city of Khartoum and the Darfur region. Later, a faction of the militant Sudan People's Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, also fought the SAF in regions bordering South Sudan and Ethiopia. As of 15 August 2023, between 4,000 and 10,000 people had been killed and 6,000 to 12,000 others injured, while as of 12 September 2023, over 4.1 million were internally displaced and more than 1.1 million others had fled the country as refugees.

Contents

Background

The history of conflicts in Sudan has consisted of foreign invasions and resistance, ethnic tensions, religious disputes, and competition over resources. In its modern history, two civil wars between the central government and the southern regions killed 1.5 million people, and a continuing conflict in the western region of Darfur has displaced two million people and killed more than 200,000 people. Since independence in 1956, Sudan has had more than fifteen military coups and it has also been ruled by the military for the majority of the republic's existence, with only brief periods of democratic civilian parliamentary rule.

Political context

Former president and military strongman Omar al-Bashir presided over the War in Darfur, a region in the west of the country, and oversaw state-sponsored violence in the region of Darfur, leading to charges of war crimes and genocide. Approximately 300,000 people were killed and 2.7 million forcibly displaced in the early part of the Darfur conflict.

Al-Bashir relied upon the janjaweed and RSF to crush uprisings by ethnic Africans in the Nuba Mountains and Darfur. In 2017, a new Sudanese law gave the RSF the status of an "independent security force". Bashir sent RSF forces to quash a 2013 uprising in South Darfur and also deployed RSF units to fight in Yemen and Libya.

In December 2018, protests against al-Bashir's regime began, the first phase of the Sudanese Revolution. Eight months of sustained civil disobedience were met with violent repression. In April 2019, the military (including the RSF) ousted al-Bashir in a coup d'état, ending his three decades of rule; the army established a Transitional Military Council, a junta. Bashir was imprisoned in Khartoum; he was not turned over to the ICC, which had issued warrants for al-Bashir's arrest on charges of war crimes.

In August 2019, after international pressure and mediation by the African Union and Ethiopia, the military agreed to share power in an interim joint civilian-military unity government (the Transitional Sovereignty Council), headed by a civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, with elections to take place in 2023. However, in October 2021, the military seized power in a coup led by Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF leader Dagalo. The Transitional Sovereignty Council was reconstituted as a military junta led by Al-Burhan, monopolizing power and halting Sudan's brief transition to democracy.

Tensions between the RSF and the Sudanese junta began to escalate in February 2023, as the RSF began to recruit members from across Sudan. A brief military buildup in Khartoum was succeeded by an agreement for de-escalation, with the RSF withdrawing its forces from the Khartoum area. The junta later agreed to hand over authority to a civilian-led government, but it was delayed due to renewed tensions between generals Burhan and Dagalo, who serve as chairman and deputy chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, respectively. Chief among their political disputes is the integration of the RSF into the military: the RSF insisted on a ten-year timetable for its integration into the regular army, while the army demanded integration within two years. Other contested issues included the status given to RSF officers in the future hierarchy, and whether RSF forces should be under the command of the army chief – rather than Sudan's commander-in-chief – who is currently al-Burhan. They have also clashed over authority over sectors of Sudan's economy that are controlled by the two factions. As a sign of their rift, Dagalo expressed regret over the October 2021 coup.

Prelude

On 11 April 2023, RSF forces deployed near the city of Merowe and in Khartoum. Government forces ordered them to leave, but they refused. This led to clashes when RSF forces took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum. On 13 April, RSF forces began their mobilization, raising fears of a potential rebellion against the junta. The SAF declared the mobilization illegal.

Timeline

The war began with attacks by the RSF on government sites as airstrikes, artillery, and gunfire were reported across Sudan. Throughout the conflict, RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan "Hemedti" Dagalo and Sudan's de facto leader and army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan have disputed control of government sites in Khartoum, including the general military headquarters, the Presidential Palace, Khartoum International Airport, Burhan's official residence, and the SNBC headquarters, as well as states and towns in Darfur and Kordofan. The two sides were then joined by rebel groups who had previously fought against the two sides. Starting in June, the SPLM-N (al-Hilu) attacked army positions in the south of the country. In July, a faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement led by Mustafa Tambour (SLM-T) officially joined the war in support of the SAF, while in August, the rebel Tamazuj movement based in Darfur and Kordofan joined forces with the RSF.

Evacuation of foreign nationals

The outbreak of violence has led foreign governments to monitor the situation in Sudan and move towards the evacuation and repatriation of its nationals. Among some countries with a number of expatriates in Sudan are Egypt, which has more than 10,000 citizens in the country, and the United States, which has more than 16,000 citizens, most of whom are dual nationals. Efforts at extraction were hampered by the fighting within the capital Khartoum, particularly in and around the airport. This has forced evacuations to be undertaken by road via Port Sudan on the Red Sea, which lies about 650 km (400 miles) northeast of Khartoum. from where they were airlifted or ferried directly to their home countries or to third ones. Other evacuations were undertaken through overland border crossings or airlifts from diplomatic missions and other designated locations with direct involvement of the militaries of some home countries. Some major transit hubs used during the evacuation include the port of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and Djibouti, which hosts military bases of the United States, China, Japan, France, and other European countries.

Humanitarian impact

The humanitarian crisis following the fighting was further exacerbated by the violence occurring during a season of high temperatures, drought and the fasting month of Ramadan. Most residents were unable to venture outside of their homes to gather food and supplies due to fears of getting caught in the crossfire. A doctors' group said that hospitals remained understaffed and were running low on supplies as wounded people streamed in. The Sudanese Doctors' Union said more than two-thirds of hospitals in conflict areas were out of service with 32 forcibly evacuated by soldiers or caught in the crossfire. The United Nations reported that shortages of basic goods, such as food, water, medicines and fuel have become "extremely acute". The delivery of badly-needed remittances from overseas migrant workers was also halted after Western Union announced it was closing all operations in Sudan until further notice.

The International Organization for Migration said on 26 April that the fighting in Sudan had produced at least 75,000 internally displaced persons. Thousands of residents fled Khartoum by foot or by vehicle to safer parts of the country. Some of them faced difficulties such as the presence of roadblocks and robberies along the roads. The Norwegian Refugee Council said that there were about 300 refugees from Khartoum who had fled southeast to El-Gadarif. 3,000 refugees from Khartoum fled to Tunaydbah refugee camp, which already hosts 28,000 Ethiopian refugees, in eastern Sudan, while at least 20,000 fled to Wad Madani. Up to 30,000 people, mainly South Sudanese refugees, moved south from Khartoum to White Nile State, which borders South Sudan. Up to 37,000 people were thought to have been displaced across Nyala, the capital of South Darfur.

Peace efforts

April

On 16 April, representatives from the SAF and the RSF agreed to a proposal by the United Nations to pause fighting between 16:00 and 19:00 local time (CAT). The SAF announced that it approved a UN proposal to open a safe passage for urgent humanitarian cases for 3 hours every day starting from 16:00 local time, and stated that it reserved the right to react if the RSF "commit[ted] any violations". Gunfire and explosives continued to be heard during the ceasefire, drawing condemnation from Special Representative Volker Perthes.

On 17 April, the governments of Kenya, South Sudan, and Djibouti expressed their willingness to send their presidents to Sudan to act as mediators. Khartoum Airport was closed due to fighting.

On 18 April, Hemedti said the RSF agreed to a day-long armistice to allow the safe passage of civilians, including those wounded. In a tweet, he said that the decision was reached following a conversation with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken "and outreach by other friendly nations". An army general later confirmed that the SAF had agreed to a 24-hour ceasefire to start at 18:00 local time (16:00 UTC). After the start of the promised ceasefire, gunfire and shelling continued to be heard in the center of Khartoum. The SAF and the RSF issued statements accusing each other of failing to respect the ceasefire. The SAF's high command said it would continue operations to secure the capital and other regions.

On 19 April, the SAF and the RSF said that they had agreed to another 24-hour ceasefire starting at 18:00 local time (16:00 GMT). Fighting continued between the two sides after the ceasefire had supposedly begun.

On 21 April, the RSF said it would observe a 72-hour ceasefire which would come into effect at 6:00 (4:00 GMT) that day, the beginning of the Islamic holiday of Eid ul-Fitr. Despite the SAF agreeing to the truce later that afternoon, fighting continued throughout the day in Khartoum and other conflict zones. A 72-hour ceasefire agreement was announced on 24 April, and fighting continued.

On 26 April, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) proposed a 72-hour extension of the ceasefire, while South Sudan offered to host mediation efforts. The SAF said it supported the plan and would send an envoy to the South Sudanese capital Juba, to participate in the talks. The RSF announced its support for the extended ceasefire on 27 April. Fighting continued after the start of the extended ceasefire.

On 30 April, the RSF announced that the ceasefire was to be further extended by 72 hours, to which the SAF later agreed. Fighting continued during this ceasefire.

May

On 1 May, United Nations Special Envoy to Sudan Volker Perthes announced that the SAF and the RSF had agreed to send representatives for negotiations mediated by UN, and did not give a date or venue for the talks.

On 2 May, South Sudan's Foreign Ministry said that the SAF and the RSF had agreed "in principle" to a week long ceasefire to start from 4 May, only for it to break down again. The Sudanese resistance committees stated that the proposed negotiations between the SAF and the RSF ignored "the only one affected by this war, the Sudanese people", and that the negotiations were aimed at the SAF and the RSF "gain[ing] popular and political support".

On 6 May, delegates from the SAF and the RSF met directly for the first time in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for what was described by the Saudis and the United States as "pre-negotiation talks". Jonathan Hutson of the Satellite Sentinel Project stated that a broad range of Sudanese civil society, "political parties, resistance committees, women's organisations, trade unions and human rights defenders", objected to both Burhan and Hemedti, seeing them as illegitimate leaders and insisted on participating in peace negotiations. The civil society activists called for paramilitary forces to be merged into the SAF under civilian authority.

On 12 May, the SAF and the RSF signed an agreement to allow safe passage for people leaving battle zones, protect relief workers and not to use civilians as human shields; there was no ceasefire agreement.

On 20 May, the SAF and the RSF agreed to a week long ceasefire starting at 21:45 local time (19:45 GMT) on 22 May, following talks in Jeddah. It was later extended until 3 June. But on 31 May, the SAF suspended negotiations, accusing the RSF of a lack of commitment on implementing the existing ceasefire agreement and violating its terms.

June

A 24-hour ceasefire was declared and implemented on 10–11 June, while a 72-hour ceasefire was declared and implemented on 18 June.

On 27 June, the RSF announced a unilateral two-day ceasefire for the Eid ul-Adha holiday. Later that same day, the SAF announced its own unilateral ceasefire for the holiday.

July

After the SPLM-N joined the conflict, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir said on 4 July that persuaded the faction's leader Abdelaziz al-Hilu to stop the attacks on the SAF. It continued fighting with the SAF in the succeeding days, prompting Kiir to hold talks again with its leaders on 20 July.

On 10 July, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional bloc composed of eight East African states, opened a summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to explore options to end the conflict. In a statement, the bloc said it had agreed to request a summit of another regional body, the Eastern Africa Standby Force, to consider the latter's possible deployment "to protect civilians and guarantee humanitarian access". The SAF boycotted the meeting after it rejected Kenyan President William Ruto as head of the committee facilitating the talks and accused Kenya of harboring the RSF. The Sudanese Foreign Ministry rejected the proposals for foreign intervention and took offense with Ethiopia and Kenya's claims that Sudan was suffering from a power vacuum.

On 13 July, Egypt hosted a summit in Cairo, wherein the SAF, the RSF and leaders of Sudan's neighboring states agreed to a new initiative to resolve the conflict. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said the initiative would include establishing a lasting cease-fire, creating safe humanitarian corridors for aid delivery, and building a dialogue framework that would include all political parties and figures in the country. He also urged the warring sides to commit to peace negotiations led by the African Union.

On 15 July, the SAF returned to negotiations with the RSF in Jeddah, but left again on 27 July, accusing the RSF of more ceasefire violations and demanding its withdrawal from Khartoum before talks could resume.

In his first video announcement since the conflict began, Hemedti said he was willing to come to a peace agreement within 72 hours if the entire SAF leadership, which he called "corrupt", were to be removed.

August

On 2 August, the SAF spokesperson, Nabil Abdallah, denied reports of an imminent ceasefire between the army and the RSF, stating that negotiations in Jeddah had stalled.

Reactions

International

On 19 April, diplomatic missions in Sudan, which included those of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union, issued a joint statement calling for fighting parties to observe their obligations under international law, specifically urging them to "protect civilians, diplomats and humanitarian actors," avoid further escalations and initiate talks to "resolve outstanding issues."

Organizations

- The African Union called for a political solution to the crisis. The body's Peace and Security Council said that it "strongly rejects any external interference that could complicate the situation in Sudan" after an emergency meeting. It also announced that the head of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki, was planning to "immediately" go on a ceasefire mission to Sudan.

- The Arab League called for an immediate end to the violence in Sudan and offered to mediate between the country's warring sides in a statement issued following an emergency meeting in Cairo.

- The European Union's foreign policy chief Josep Borrell confirmed EU staff were all accounted for and called for an immediate end to the violence. He also called the attack on its Ambassador Aidan O'Hara in Khartoum a gross violation of the Vienna Convention. EU spokeswoman Nabila Massrali told AFP news agency the EU delegation had not been evacuated from Khartoum following the attack.

- The Intergovernmental Authority on Development, an East African trade bloc, held an emergency meeting on the situation in Sudan and said it plans to send Kenyan President William Ruto, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and Djiboutian President Ismail Omar Guelleh to Khartoum as soon as possible to reconcile the conflicting groups.

- United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres called for an immediate cessation of all hostilities. He also expressed concern that the conflict in Sudan could escalate into a disastrous regional conflict.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra civil sudanesa (2023-presente) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra civil sudanesa (2023-presente) para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |