Uranium mining and the Navajo people facts for kids

In the 1950s, the Navajo Nation was situated directly in the uranium mining belt that experienced a boom in production, and many residents found work in the mines. Prior to 1962, the risks of lung cancer due to uranium mining were unknown to the workers, and the lack of a word for radiation in the Navajo language left the miners unaware of the associated health hazards. The cultural significance of water for the Navajo people and the environmental damage to both the land and livestock inhibits the ability of the Navajo people to practice their culture.

The Navajo Nation was affected by the United States' largest radioactive accident during the Church Rock uranium mill spill in 1979 when a tailings pond upstream from Navajo County breached its dam and sent radioactive waste down the Puerco River, injuring people and killing livestock.

In the Navajo Nation, approximately 30% of people do not have access to running water. Navajo Nation residents are 67 times more likely to live without running water than the general population, and are often forced to resort to unregulated water sources that are susceptible to bacteria, fecal matter, and uranium. Extensive uranium mining in the region during the mid-20th century is a contemporary concern because of contamination of these commonly used sources, in addition to the lingering health effects of exposure from mining.

Water in the Navajo Nation currently has an average of 90 micrograms per liter of uranium, with some areas reaching upwards of 700 micrograms per liter. In contrast, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers 30 micrograms per liter the safe amount of uranium to have in water sources. Health impacts of uranium consumption include kidney damage and failure, as kidneys are unable to filter uranium out of the bloodstream. There is an average rate of End Stage Renal Disease of 0.63% in the Navajo Nation, a rate significantly higher than the national average of 0.19%.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been cleaning up uranium mines in the Navajo Nation since as part of settlements through the Superfund since 1994. The Abandoned Mine Land program and Contaminated Structures Program have facilitated the cleanup of mines and demolition of structures built with radioactive materials. Criticisms of unfair, inefficient treatment have been made repeatedly of EPA by Navajos and journalists.

In October 2021, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights agreed to hear a case filed by the Eastern Navajo Diné Against Uranium Mining, which accused the United States government of violating the human rights of Navajo Nation members.

Contents

History

In 1944, uranium mining under the U.S military's Manhattan Project began on Navajo Nation lands and on Lakota Nation lands. On August 1, 1946, the responsibility for atomic science and technology was transferred from the military to the United States Atomic Energy Commission. Afterward, widespread uranium mining began on Navajo and Lakota lands in a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Large uranium deposits were mined on and near the Navajo Reservation in the Southwest, and these were developed through the 20th century. Absent much environmental regulation prior to the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and passage of related laws, the mining endangered thousands of Navajo workers, as well as producing contamination that has persisted in adversely affecting air and water quality, and contaminating Navajo lands.

Private companies hired thousands of Navajo men to work the uranium mines. Disregarding the known health risks of exposure to uranium, the private companies and the United States Atomic Energy Commission failed to inform the Navajo workers about the dangers and to regulate the mining to minimize contamination. As more data was collected, they were slow to take appropriate action for the workers.

In 1951, the U.S. Public Health Service began a human testing experiment on Navajo miners, without their informed consent, during the federal government's study of the long term health effects from radiation poisoning. In 1932, the USPHS began an earlier human testing experiment on African men in their Tuskegee experiment. The experiment on Navajo mine workers and their families documented high rates of cancers (including Xeroderma pigmentosum) and other diseases which manifested from uranium mining and milling contamination. For decades, industry and the government failed to regulate or improve conditions, or inform workers of the dangers. As high rates of illness began to occur, workers were often unsuccessful in court cases seeking compensation, and the states at first did not officially recognize radon illness. In 1990, the US Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, to address cases of uranium poisoning and provide needed compensation, but Navajo Nation applicants provide evidence RECA requirements prevent access to necessary compensation. Congressional modifications to RECA application requirements were made in 2000, and were introduced in 2017 and in 2018.

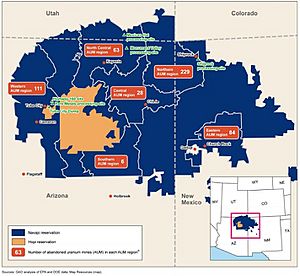

Since 1988, the Navajo Nation's Abandoned Mine Lands program reclaims mines and cleans mining sites, but significant problems from the legacy of uranium mining and milling persist today on the Navajo Nation and in the states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. More than a thousand abandoned mines have not been contained and cleaned up, and these present environmental and health risks in Navajo communities. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that there are 4000 mines with documented uranium production, and another 15,000 locations with uranium occurrences in 14 western states. Most are located in the Four Corners area and Wyoming.

The Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act (1978) is a United States environmental law that amended the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 and authorized the Environmental Protection Agency to establish health and environmental standards for the stabilization, restoration, and disposal of uranium mill waste. Cleanup has continued to be difficult, and EPA administers several Superfund sites located on the Navajo Nation.

On April 29, 2005, Navajo Nation President Joe Shirley Jr. signed the Diné Natural Resources Protection Act of 2005 that outlaws uranium mining and processing on Navajo Nation lands.

Pressure for uranium mining increased in the postwar years, when the United States developed resources to compete with the Soviet Union in the Cold War. In 1948, the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) announced it would be the sole purchaser of any uranium mined in the United States, to cut off dependence on imported uranium. The AEC would not mine the uranium; it contracted with private mining companies for the product. The subsequent mining boom led to the creation of thousands of mines; 92% of all western mines were located on the Colorado Plateau because of regional resources.

The Navajo Nation encompasses portions of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, and their reservation was a key area for uranium mining. More than 1000 mines were established by leases in the reservation. From 1944 to 1986, an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 Navajo people worked in the uranium mines on their land. Other work was scarce on and near the reservation, and many Navajo men traveled miles to work in the mines, sometimes taking their families with them. Between 1944 and 1989, 3.9 million tons of uranium ore were mined from the mountains and plains.

In 1951, the US Public Health Service began a massive human medical experiment on approximately 4000 Navajo uranium miners, without their informed consent. Neither the miners nor their families were warned of the risks from nuclear radiation and contamination as USPHS continued their experiment. In 1955, USPHS took active control of Native American medical health services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the experiments on nuclear radiation continued. In 1962 it published the first report to show a statistical correlation between cancer and uranium mining. The federal government finally regulated the standard amount of radon in mines, setting the level at .3 working level (WL) on January 1, 1969, but Navajo people attending mining schools before working in the mines were still not informed of the health risks from uranium poisoning in 1971. Reports continued to be published from USPHS's non-consensual medical experiments at least until 1998. The Environmental Protection Agency was established on December 2, 1970. But, environmental regulation could not repair the damage already suffered. Navajo miners contracted a variety of cancers including lung cancer at much higher rates than the rest of the U.S. population, and they have suffered higher rates of other lung diseases caused by breathing in radon.

Private companies resisted regulation through lobbying Congress and state legislatures. In 1990, the United States Congress finally passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), granting reparations for those affected by the radiation. The act was amended in 2000 to address criticisms and problems with the original legislation.

The tribal council and Navajo delegates remained in control of mining decisions before the adverse health effects of mining were identified. No one fully understood the effect of radon exposure for miners, as there was insufficient data before the expansion of mining.

Church Rock uranium mill spill

On July 16, 1979, the tailings pond at United Nuclear Corporation's uranium mill in Church Rock, New Mexico, breached its dam. More than 1,000 tons of radioactive mill waste and 93 million gallons of acidic, radioactive tailings solution and mine effluent flowed into the Puerco River, and contaminants traveled 80 miles (130 km) downstream to Navajo County, Arizona. The flood backed up sewers, affected nearby aquifers and left stagnating, contaminated pools on the riverside.

More radioactivity was released in the spill than in the Three Mile Island accident that occurred four months earlier. It has been reported as the largest radioactive accident in U.S. history.

The state contingency plan relied on English-only notification of the largely Navajo public populace affected by the spill. Local residents did not learn immediately of the toxic danger. The locals were accustomed to using the riverside for recreation and herb gathering. Residents who waded in the acidic water went to the hospital complaining of burning feet and were misdiagnosed with heat stroke. Sheep and cattle died en masse. The Navajo Nation asked the governor of New Mexico to request disaster assistance from the US government and have the site declared a disaster area, but the governor refused. This limited the amount of disaster relief the Navajo Nation received.

For nearly two years, the state and federal government trucked in water to the reservation, but ended the program in 1981. Farmers had little choice but to resume use of the river for watering livestock and crops.

Abandoned Mine Land Program

The Navajo Nation Abandoned Mine Land(s) (NN AML) are numerous United States Environmental Protection Agency-designated "AML sites" on lands of the Navajo people which were used for mining (e.g., uranium). Sites include:

- Abandoned Uranium Mines on the Navajo Nation, Arizona (Site NNN000906087); a region with many of the "521 abandoned uranium mine areas".

- Skyline Abandoned Uranium Mine, Utah; in Monument Valley at Oljato Mesa (the waste piles area has a distinct site number)

- Skyline AUM Waste Piles (NN000908358)

- Northeast Church Rock Mine, New Mexico (NECR, NNN000906132); "mostly on Navajo tribal trust land", "the highest priority abandoned mine cleanup in [sic] the Navajo Nation", and a site which adjoins the United Nuclear Corporation (UNC) uranium mill Superfund site "on private fee land".

"During the late 1990s, portions...were closed by the Navajo Nation Abandoned Mine Land program".

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) maintains a partnership with the Navajo Nation. Since 1994, the Superfund Program has provided technical assistance and funding to assess potentially contaminated sites and to develop a response. The EPA has entered into enforcement agreements and settlements valued at over $1.7 billion to reduce the highest risks of radiation exposure to the Navajo people from AUMs (Abandoned Uranium Mines). As a result, funds are available to begin the assessment and cleanup process at 219 of the 523 abandoned uranium mines as of May 2019.

The Abandoned Uranium Mine Settlement fact sheet provides information on the abandoned-uranium-mines enforcement agreements and settlements to address abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. To learn more about EPA's Superfund legal agreements please visit Negotiating Superfund Settlements. Uranium mining took place on the Navajo Nation from 1944 to 1986, and some local residents used materials from uranium mines when building their homes Mining materials that were used can potentially lead to exposure exceeding background (naturally occurring) levels. These materials include ore and waste rock used for foundations, walls, or fireplaces; mine tailings mixed into cement used for foundations, floors, and cinder block walls; and other contaminated building materials (wood, metal, etc.) that may have been salvaged from the abandoned mine areas.

The EPA and the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency's (NNEPA) Contaminated Structures Program evaluates structures on Navajo Nation that may have been constructed using abandoned mine materials or built on or near abandoned mines. The Contaminated Structures Program is responsible for conducting evaluations of potentially contaminated structures, yards and material, as well as removal and cleanup of contaminated structures and materials if there is an exposure risk. The program is for Navajo residents living close to mines or who know their home was built with contaminated materials. Participation in the program is voluntary and at no cost to the resident. USEPA and NNEPA have completed over 1,100 assessments on Navajo Nation since the program began in 2007.

History

This specific Superfund site for the AUMs on Navajo land has been in existence since 1994. This is following many years of research on the health effects of uranium mining which eventually led to the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 1990. Since its acceptance as a Superfund site, many federal, tribal, and grassroots organizations have come together to assess and remediate contamination sites on the Navajo Nation. Due to the fact that there are hundreds of contaminated sites, there have been a few big successes and many communities stuck in limbo. The following is a history of this Superfund site, the organizations that have collaborated on this environmental remediation, and recent criticisms of the handling of this large and complicated problem.

The Abandoned Uranium Mines on the Navajo Nation were established as a Superfund site in 1994 in response to a Congressional hearing brought by the Navajo Nation on November 4, 1993. This hearing included the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Energy (DOE), and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Superfund status stems from the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) which allows the United States federal government to assign funds for environmental remediation of uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. The Navajo Nation is located in Region 9 (Pacific Southwest) of the Superfund which serves Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, the Pacific Islands, and Tribal Nations. The site's official EPA # is NNN000906087 and it is located in Congressional District 4. According to the EPA's Superfund site overview, other names for the AUMs may include "Navajo Abandoned Uranium Mines" or "Northeast Church Rock Mine." Church Rock Mine is one of the EPA's most successful clean-up sites among over 500 sites spanning the 27,000 square mile Navajo Nation.

Nearly four years after the initial Congressional hearing, the EPA announced their first helicopter survey for the AUMs in September 1997. Located in the Oljato area in Southeastern Utah near the Utah-Arizona border, this was first of several helicopter surveys that aimed to measure "naturally occurring radiation (gamma radiation) coming from abandoned uranium mining areas." The stated purpose of these surveys was to "determine if these sites pose a risk to the people in the area and if so, what measures should be taken to minimize that risk."

Over ten years later, on June 9, 2008, the EPA announced its five-year plan for the clean-up of uranium contamination on the Navajo Nation. This five-year plan contained nine specific objectives for 2008–2012: assess up to 500 contaminated structures and remediate those that pose a health risk; assess up to 70 potentially contaminated water sources and assist those affected by it; assess and require cleanup of AUMs via a tiered ranking system of high priority mines; clean Church Rock Mine, the highest-priority mine; remediate groundwater of abandoned uranium milling sites; assess the Highway 160 site; assess and clean Tuba City Dump; assess and treat health conditions for populations near AUMs; and lastly to summarize the action of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in its assistance to the Navajo Nation's cleanup efforts. Since the introduction of the five-year plan, the EPA has released a progress report (available online) each consecutive year. As of August 2011, the EPA lists its accomplishments as: screening 683 structures, sampling 250 unregulated water sources and shutting down 3 such contaminated sources, provision of public outreach and educational programs for safe water practices, instituting a 2.6 million dollar water hauling feasibility project, and providing up to 386 homes with clean drinking water through a 20 million dollar project with Indian Health Services. For 2012, the EPA has listed its next steps as replacing 6 contaminated structures, demolishing other contaminated structures, and continuing screening of these structures for referral to the EPA's Response Program. The 2011 progress report also lists Church Rock, the Oljato Mesa, and the Mariano Lake Mine as sites of current or proposed remediation.

According to the EPA's website, the AUM Superfund site is not on the National Priorities List (NPL) and has no proposals to be put on this list. The NPL is the list of hazardous Superfund sites that are deemed eligible for long-term environmental remediation. The EPA suggests that although NPL listing is a possibility it is "not likely" for the abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo nation. NPL status guides the EPA in its decisions on sites to further investigate, a process that has been criticized for the handling of these mines. With over 500 uranium sites and only a few sites slated for full-scale remediation plans, the prioritization process has recently been called into question by The New York Times (see Recent Press).

Partnership agencies

Superfund works with many agencies from both the federal government and the Navajo Nation in order to properly assess and direct funding to mining sites. These agencies include: the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency (NNEPA), the Indian Health Services (IHS), the Diné Network for Environmental Health (DiNEH), the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources (NNDWR), the Department of Energy (DOE), and US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). The NNEPA was established in 1972 and officially recognized through legislation as a separate regulatory branch of the Navajo Nation in 1995. With the official acceptance of the NNEPA also came the adoption of the Navajo Nation Environmental Policy Act. According to the NNEPA website, their mission is: "With respect to Diné values, to protect human health, land, air and water by developing, implementing and enforcing environmental laws and regulations with a commitment to public participation, sustainability, partnership, and restoration." (Diné is the word for Navajo in the traditional Navajo language) NNEPA consults with the US EPA on site assessments (the US EPA is the lead agency for the Site Assessment Project). NNEPA helps the EPA in assessing and deciding which contaminated structures should be demolished and which water sources should be deemed a human health risk. The two also collaborate to perform community outreach for the Navajo people whose lives are affected by the uranium mining. The Center for Disease Control and the DiNEH Project are also integral players in the assessment of water quality and community outreach. The Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, with funding from the EPA, assist Navajo residents by hauling water for residents near 4 contaminated water sources, a 2.6 million dollar project. Indian Health Services helped fund the 20 million dollar drinking water project started in 2011. This project serves 386 homes near 10 contaminated water sources. The NNEPA, IHS, NNDWR, and DiNEH project have been the main partners with the US EPA in water hauling projects.

Criticism and press

Despite the EPA's claims of a "strong partnership with the Navajo Nation," recent articles have been published that call into question the equitability and efficiency of the EPA's action on the abandoned uranium mines. On March 31, 2012, The New York Times published an article entitled "Uranium Mines Dot Navajo Land, Neglected and Still Perilous" by Leslie MacMillan. The article suggests that politics and money are influencing the prioritization of mine clean-up efforts. David Shafer, an environmental manager at the United States Department of Energy, has said that questions of whether current uranium problems are due to past mining or to the naturally occurring mineral are delaying the process of cleaning up. Similar concerns are common in environmental remediation projects for victims of industrial pollution.

While the EPA does prioritize mines that are nearest to people's homes, MacMillan highlights some remote locations where people do live and yet have been neglected by the EPA. Cameron, Arizona is one such site which has a population of nearly 1000. Rancher Larry Gordy stumbled across an abandoned uranium mine on his grazing land for his cattle near Cameron in the summer of 2010. There are still no warning signs in the town of Cameron to alert people of potential contamination. On December 30, 2010 Scientific American published an article entitled "Abandoned Uranium Mines: An 'Overwhelming Problem' in the Navajo Nation" by Francie Diep. Diep told Gordy's story and reported that the EPA assessed his site on November 9, 2010. Diep suggested that this date was moved up due to publicity of Gordy's story; originally the EPA had promised to visit within six months of his original discovery of the uranium mine.

Similar allegations of prioritization due to negative publicity for the EPA were made of the Skyline Mine in the Oljato Mesa. Elsie Begay, a 71-year-old Navajo woman from the Oljato region was the topic of a series of articles in The Los Angeles Times in 2006. These articles were written by Yellow Dirt: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed (2010) author Judy Pasternak, whose work on these articles led to her book. One EPA representative, Jason Musante, stated this publicity "might have bumped the site up the priority list."

Over a year after Gordy stumbled across the mine in his cattle's grazing land, MacMillan reports that the site at Cameron has yet to be given a priority by the EPA. When EPA officials were asked to accompany a reporter to the Cameron site, the officials declined and instead offered to visit the newly cleaned site in Oljato. MacMillan spoke with a Navajo hotel manager near the Skyline Mine who expressed hesitation about the EPAs remediation, stating, "That's what they want you to see: something that's all nice and cleaned up." MacMillan drew attention to the fact that cows are grazing on contaminated land and people are eating these cattle. Taylor McKinnon, a director at the Center for Biological Diversity, went so far as to say the site was the "worst he had seen in the Southwest." Although the locally grown beef is tested, standard tests for meat do not include checking for radioactive substances like uranium. The EPA has put an emphasis on health effects throughout its five-year plan, so the lack of any sort of attention in this matter has raised eyebrows.

In addition to the questioning of political bias in the prioritization of mining sites, there is criticism of the EPA's decision to revisit a 1989 permit proposing to mine for uranium near Church Rock. New Mexico's KUNM radio station reported on May 9, 2012 that Uranium Resources Incorporated has expressed interest in starting production near Church Rock by the end of 2013. An online petition has already gained nearly 10,000 signatures against this new mining initiative.

Clean-up efforts

Since 1994, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), along with the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency, has been mapping areas affected with radioactivity. In 2007, they compiled an atlas of the abandoned uranium mills in order to rid the area of nuclear waste. In 2008, the EPA implemented a five-year cleanup plan, focusing on the most pressing issues: contaminated water and structures. The EPA estimates that 30% of all Navajo people lack access to uncontaminated drinking water.

The EPA is targeting 500 abandoned uranium mills as another part of their five-year cleanup plan, with the goal of ridding the area of nuclear waste. Its priority was identification of contaminated water sources and structures; many of the latter have been destroyed and removed. In 2011, it completed a multi-year project of removing 20,000 cubic yards of contaminated earth out of the reservation, near the Skyline Mine, to controlled storage on the plateau.

In 2017, a $600 million settlement attempts to clean up 94 abandoned uranium mines.

The EPA and NNEPA prioritized 46 mines (called priority mines) based on gamma radiation levels, proximity to homes and potential for water contamination identified in preliminary assessments documented in the EPA Site Screen Reports. Detailed cleanup investigations will be conducted at these mines by the end of 2019. All documents can be found here.

All 46 priority mines are in the assessment phase which includes biological and cultural surveys, radiation scanning, and soil and water sampling. These assessments help to determine the extent of contamination. The assessment work at the 46 priority mines will be documented in Removal Site Evaluation reports which will be completed by the end of 2019. These reports will be shared with communities and made available on this website.

The federal government seeks proposals from businesses to clean up abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. $220 million available to small businesses to clean up Navajo uranium mines. The funding comes from a $1.7 billion settlement with Tronox, the successor of Kerr-McGee, a company that mined the region. During the Cold War companies extracted nearly 30 million tons of uranium from Navajo land. The EPA says it has funding to assess and clean up 220 of the 520 abandoned mines. The Request for Proposal can be found at www.fedconnect.net in the “Public Opportunities” section by searching Reference Number 68HE0918R0014. Contract proposals will be accepted through May 28, 2019.

Residents of the Red Water Pond Road area have requested relocation to a new, off-grid village to be located on Standing Black Tree Mesa while cleanup progresses on the Northeast Church Rock Mine Superfund site, as an alternative to the EPA-proposed relocation of residents to Gallup.