Stamp Act facts for kids

A stamp act is a law that puts a tax on the transfer of some documents. Those that pay the tax get an official stamp on their documents. Many products have been covered by stamp acts such as playing cards, patent medicines, cheques, mortgages, contracts and newspapers. The items often have to be physically stamped at approved government offices following payment of the duty, although other methods with annual payment of a fixed sum or purchase of adhesive stamps are more practical and common. Stamp acts have been made common in many countries, like Australia, China, Canada, Ireland, Malaysia, Israel, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The money raised by the tax, called stamp duty, was first used in the Netherlands in 1624 after a public competition to find a new form of tax. However, it has more been used in Great Britain and its colonies.

United States

Stamp Act 1765

After Great Britain was victorious over France in the Seven Years' War – which manifested in America as the French and Indian War – a small Stamp Act was enacted that covered all sorts of documents. The Stamp Act 1765 (short title Duties in American Colonies Act 1765; 5 Geo. 3. c. 12) was a direct tax imposed by the British Parliament on the colonies of British America. The act required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper produced in London and carrying an embossed revenue stamp. These printed materials were on every legal document, magazine, and newspaper, plus many other types of paper used throughout the colonies, including playing cards. Unlike previous taxes, the stamp tax had to be paid in valid British currency, not in colonial paper money.

The purpose of the tax was to help pay for troops stationed in North America. The British government felt that the colonies were the primary beneficiaries of this military presence, and the colonial population should pay at least a portion of the expense. The colonists claimed their constitutional rights were violated since only their own colonial legislatures could levy taxes. The colonies sent no representatives to Parliament, and therefore had no influence over what taxes were raised, how they were levied, or how they would be spent. Some opponents of the Stamp Act distinguished between "internal" taxes like the stamp duty, which they claimed Parliament had no right to impose, and revenue legitimately raised through the regulation on trade. In general, however, most colonists considered the Act to be a violation of their rights as Englishmen to be taxed without their consent – consent that only the colonial legislatures could grant because Americans were unrepresented in Parliament. The rallying cry of "No Taxation without Representation" reflected an increasingly major grievance that led to the American Revolution. The Americans saw no need for the troops or the taxes; the British saw colonial defiance of their lawful rulers.

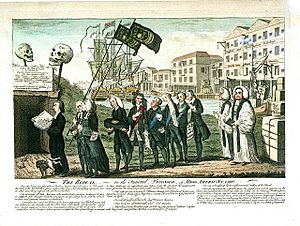

The Stamp Act met great resistance in the colonies. Colonial assemblies sent petitions and protests. Local protest groups, led by colonial merchants and landowners, established connections through correspondence – the so-called "Committees of Correspondence – that created a loose coalition extending from New England to Georgia. British goods were boycotted. Opposition to the tax also took the form of violence and intimidation. Custom houses and tax collectors were attacked. Protests and demonstrations initiated by the newly formed Sons of Liberty often turned violent and destructive as the masses became involved. A word used frequently by colonists was "liberty" during the Stamp Act upheaval. Opponents of the new tax staged mock funerals in which "liberty's" coffin was carried to a burial ground. They insisted that liberty could not be "taken away without consent."

A more reasoned approach was taken by some elements. James Otis, Jr. wrote the most influential protest, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved. Otis, the radical leader in Massachusetts, convinced the Massachusetts assembly to send a circular letter to the other colonies, which called for an inter-colonial meeting to plan tempered resistance. The Stamp Act Congress convened in New York City on October 7, 1765, with nine colonies in attendance; others would likely have participated if earlier notice had been provided. The Stamp Act Congress was another step in the process of attempted common problem-solving. The Albany Congress in 1754 had been held at the urging of royal officials as a forum for voicing constitutional concerns and afforded the more conservative critics of British policy some hope of regaining control of events from the unruly mobs in the streets of many cities; in contrast, the Stamp Act Congress was strictly a colonial affair, reflecting the first significant joint colonial response to any British measure. Delegates to the Stamp Act Congress approved a fourteen-point Declaration of Rights and Grievances as a petition to the Parliament and the King, formulated largely by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania. The statement echoed the recent resolves of the Virginia House of Burgesses, which argued that colonial taxation could only be carried on by their own assemblies. The delegates singled out the Stamp Act and the use of the vice-admiralty courts for special criticism, yet ended their statement with a pledge of loyalty to the King.

Opposition to the Stamp Act was not limited to the colonies. In Canada, Nova Scotia largely ignored the Act; they allowed ships bearing unstamped papers to enter its ports, and business continued unabated after the distributors ran out of stamps. Newfoundland experienced some protests and petitions based on legislation dating back to the reign of Edward VI forbidding any sort of duties on the importation of goods related to its fisheries. The Caribbean colonies also protested. Political opposition was expressed in a number of colonies, including Barbados and Antigua, and by absentee landowners living in Britain. The worst violence took place on St. Kitts and Nevis, with rioting and blockage of stamp delivery. Montserrat and Antigua also succeeded in avoiding the use of stamps. In Jamaica there was also vocal opposition, and much evasion of the stamps. British merchants and manufacturers, whose exports to the colonies were threatened by colonial boycotts, also pressured Parliament.

The act was repealed in early 1766, although the Declaratory Act maintained Parliament's right to tax the colonies.

Revival

"Revenue stamps" were revived in the United States during the American Civil War. In 1862, the United States (Union) government began taxing a variety of goods, services, and legal dealings, in an effort to raise revenue for the great costs of the war. To confirm that taxes were paid a "revenue stamp" was purchased and appropriately affixed to the taxable item. This excise tax continued until the federal government finished paying the war debt in 1883, at which time the tax was repealed.

In 1898, revenue stamps were again issued, to provide funding for the Spanish–American War. Tax was levied on a wide range of goods and services including alcohol, tobacco, tea, and other amusements and also on various legal and business transactions such as stock certificates, bills of lading, manifests, and marine insurance. To pay these tax duties revenue tax stamps were purchased and affixed to the taxable item or respective certificate.