Speed limit facts for kids

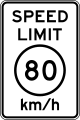

Speed limits on road traffic, as used in most countries, set the legal maximum speed at which vehicles may travel on a given stretch of road. Speed limits are generally indicated on a traffic sign reflecting the maximum permitted speed - expressed as kilometres per hour (km/h) and/or miles per hour (mph). Speed limits are commonly set by the legislative bodies of national or provincial governments and enforced by national or regional police and judicial authorities. Speed limits may also be variable, or in some places nonexistent, such as on most of the Autobahnen in Germany.

The first numeric speed limit for automobiles was the 10 mph (16 km/h) limit introduced in the United Kingdom in 1861.

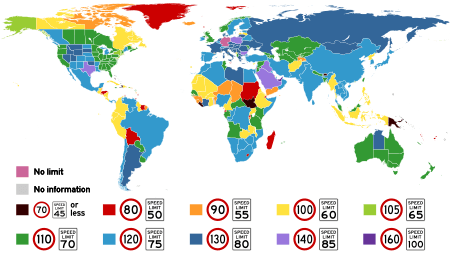

As of 2018[update] the highest posted speed limit in the world, 160 km/h (99 mph), applied on two motorways in the UAE. Speed limits and safety distance are poorly enforced in the UAE, specifically on the Abu Dhabi to Dubai motorway - which results in dangerous traffic, according to a French-government travel-advisory. Additionally, "drivers often drive at high speeds [and] unsafe driving practices are common, especially on inter-city highways. On highways, unmarked speed bumps and drifting sand create additional hazards", according to an American-government travel-advisory.

There are several reasons to regulate speed on roads. It is often done in an attempt to improve road traffic safety and to reduce the number of casualties from traffic collisions. The World Health Organization (WHO) identified speed control as one of a number of steps that can be taken to reduce road casualties. As of 2021, the WHO estimates that approximately 1.3 million people die of road traffic crashes each year.

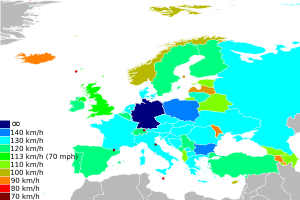

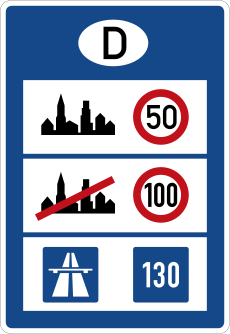

Authorities may also set speed limits to reduce the environmental impact of road traffic (vehicle noise, vibration, emissions) or to enhance the safety of pedestrians, cyclists, and other road-users. For example, a draft proposal from Germany's National Platform on the Future of Mobility task force recommended a blanket 130 km/h (81 mph) speed limit across the Autobahnen to curb fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Some cities have reduced limits to as little as 30 km/h (19 mph) for both safety and efficiency reasons. However, some research indicates that changes in the speed limit may not always alter average vehicle speed. Lower speed-limits could reduce the use of over-engineered vehicles.

History

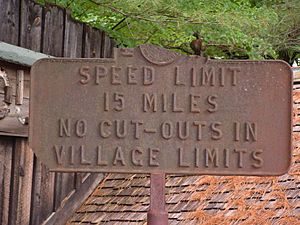

In western cultures, speed limits predate the use of motorized vehicles. In 1652, the American colony of New Amsterdam passed a law stating, "No wagons, carts or sleighs shall be run, rode or driven at a gallop." The punishment for breaking the law was "two pounds Flemish," the equivalent of US $50 in 2019. The 1832 Stage Carriage Act introduced the offense of endangering the safety of a passenger or person by "furious driving" in the United Kingdom (UK).

A series of Locomotive Acts (in 1861, 1865 and 1878) created the first numeric speed limits for mechanically propelled vehicles in the UK; the 1861 Act introduced a UK speed limit of 10 mph (16 km/h) on open roads in town, which was reduced to 2 mph (3 km/h) in towns and 4 mph (6 km/h) in rural areas by the 1865 "Red Flag Act." The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896, which raised the speed limit to 14 mph (23 km/h) is celebrated by the annual London to Brighton Veteran Car Run.

On 28 January 1896, the first person to be convicted of speeding is believed to be Walter Arnold of East Peckham, Kent, UK, who was fined 1 shilling plus costs for speeding at 8 mph (13 km/h).

In 1901, Connecticut was the first state in the United States to impose a numerical speed limit for motor vehicles, setting the maximum legal speed to 12 mph in cities and 15 mph on rural roads. Speed limits then propagated across the United States; by 1930 all but 12 states had established numerical limits.

In 1903, in the UK, the national speed limit was raised to 20 mph; however, as this was difficult to enforce due to the lack of speedometers, the 1930 "Road Traffic Act" abolished speed limits entirely. In 1934, a new limit of 30 mph was imposed in urban centers, and in July 1967, a 70 mph national speed limit was introduced.

In Australia, during the early 20th century, there were people reported for "furious driving" offenses. One conviction in 1905 cited a vehicle furiously driving 20 mph (32 km/h) when passing a tram traveling at half that speed.

In May 1934, the Nazi-era "Road Traffic Act" imposed the first nationwide speed limit in Germany.

In the 1960s, in continental Europe, some speed limits were established based on the V85 speed, (so that 85% of drivers respect this speed).

In 1974, Australian speed limits underwent metrication: the urban speed limit of 35 mph (56 km/h) was converted to 60 km/h; the rural speed limits of 60 mph (97 km/h) and 65 mph (105 km/h) were changed to 100 km/h (62 mph) and 110 km/h (68 mph) respectively.

In 2010, Sweden defined the Vision Zero program, a multi-national road traffic safety project that aims to achieve a highway system with no fatalities or serious injuries involving road traffic.

Regulations

Most jurisdictions use the metric speed unit of kilometers per hour, while others, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, use speed limits given in miles per hour. Although there have been discussions about a switch to using metric units in countries' other systems (see Metrication in the United Kingdom and Metrication in the United States), there are currently no proposals to change these laws.

Basic rule

Vienna Convention on Road Traffic

In countries bound by the Vienna Conventions on Road Traffic (1968 & 1977), Article 13 defines a basic rule for speed and distance between vehicles:

Every driver of a vehicle shall in all circumstances have his vehicle under control to be able to exercise due and proper care and to be at all times in a position to perform all manœuvres required of him. He shall, when adjusting the speed of his vehicle, pay constant regard to the circumstances, in particular the lie of the land, the state of the road, the condition and load of his vehicle, the weather conditions and the density of traffic, so as to be able to stop his vehicle within his range of forward vision and short of any foreseeable obstruction. He shall slow down and if necessary stop whenever circumstances so require, and particularly when visibility is not excellent.

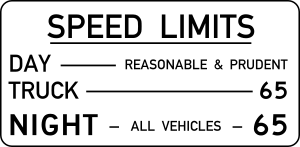

Reasonable speed

Most legal systems expect drivers to drive at a safe speed for the conditions at hand, regardless of posted limits.

In the United Kingdom, and elsewhere in common law, this is known as the reasonable man requirement.

The German Highway Code (Straßenverkehrs-Ordnung) section on speed begins with the statement (translated to English):

Any person driving a vehicle may only drive so fast that the car is under control. Speeds must be adapted to the road, traffic, visibility and weather conditions as well as the personal skills and characteristics of the vehicle and load.

In France, the law clarifies that even if the speed is limited by law and by local authority, the driver assumes the responsibility to control a vehicle's speed, and to reduce that speed in various circumstances (such as when overtaking a pedestrian or bicycle, individually or in a group; when overtaking a stopped convoy; when passing a transportation vehicle loading or unloading people or children; when the road does not appear clear, or risky; when visibility is low; when the road descends rapidly; when road sections are small, busy, or residential in nature; when approaching the top of a hill; when nearing a crossing where visibility is uncertain; when specific lights are used; or when overtaking animals. If drivers do not master their speed, or do not reduce it in such cases, they can be penalized. Other qualifying conditions include driving through fog, heavy rain, ice, snow, gravel, or when drivers encounter sharp corners, a blinding glare, darkness, crossing traffic, or when there is an obstructed view of orthogonal traffic—such as by road curvature, parked cars, vegetation, or snow banks—thus limiting the Assured Clear Distance Ahead (ACDA).

In the United States, this requirement is referred to as the basic rule, as outlined by US federal government law (49 CFR 392.14), which applies in all states as permitted under the commerce clause and due process clause. The basic speed law is almost always supplemented by specific maximum or minimum limits but applies regardless. In California, for instance, Vehicle Code section 22350 states that "No person shall drive a vehicle upon a highway at speed greater than is reasonable ... and in no event at a speed which endangers the safety of persons or property". The reasonable speed may be different than the posted speed limit. Basic rule speed laws are statutory reinforcements of the centuries-old common law negligence doctrine as specifically applied to vehicular speed. Citations for violations of the basic speed law without a crash have sometimes been ruled unfairly vague or arbitrary, hence a violation of the due process of law, at least in the State of Montana. Even within states, differing jurisdictions (counties and cities) choose to prosecute similar cases with differing approaches.

Excessive speed

Consequential results of basic law violations are often categorized as excessive speed crashes; for example, the leading cause of crashes on German autobahns in 2012 fell into that category: 6,587 so-called "speed related" crashes claimed the lives of 179 people, which represented almost half (46.3%) of 387 autobahn fatalities in 2012. However, "excessive speed" does not necessarily mean the speed limit was exceeded, rather that police determined at least one party traveled too fast for existing conditions. Examples of conditions where drivers may find themselves driving too fast include wet roadways (due to rain, snow, or ice), reduced visibility (due to fog or "white out" snow), uneven roads, construction zones, curves, intersections, gravel roads, and heavy traffic. Per distance traveled, consequences of inappropriate speed are more frequent on lower speed, lower quality roads; in the United States, for example, the "speeding fatality rate for local roads is three times that for Interstates".

For speed management a distinction can exist between excess speed which consists of driving in excess of the speed limit, and inappropriate speed which consists of going too fast for the conditions.

Maximum speed limits

Most countries have a legally assigned numerical maximum speed limit which applies on all roads when no other speed limit indications are present; lower speed limits are often shown on a sign at the start of the restricted section, although the presence of streetlights or the physical arrangement of the road may sometimes also be used instead. A posted speed limit may only apply to that road or to all roads beyond the sign that defines them depending on local laws.

The speed limit is commonly set at or below the 85th percentile operating speed (being the speed which no more than 15% of traffic exceeds), and in the US is frequently set 4 to 8 mph (6 to 13 km/h) below that speed. Thus, if the 85th percentile operating speed as measured by a "Traffic and Engineering Survey" exceeds the design speed, legal protection is given to motorists traveling at such speeds (design speed is "based on conservative assumptions about the driver, the vehicle, and roadway characteristics"). The theory behind the 85th percentile rules is that, as a policy, most citizens should be deemed reasonable and prudent, and limits must be practical to enforce. However, there are some circumstances where motorists do not tend to process all the risks involved, and as a mass, choose a poor 85th percentile speed. This rule, in practice, is a process for "voting the speed limit" by driving, in contrast to delegating the speed limit to an engineering expert.

The maximum speed permitted by statute, as posted, is normally based on ideal driving conditions and the basic speed rule always applies. Violation of the statute generally raises a rebuttable presumption of negligence.

On international European roads, speed should be taken into account during the design stage.

| Road classification | 60 km/h | 80 km/h (50 mph) | 100 km/h (60 mph) | 120 km/h (75 mph) | 140 km/h (85 mph) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motorway | x | 80 | 100 | 120 | 140 |

| Express road | 60 | 80 | 100 | 120 | x |

| Road | 60 | 80 | 100 | x | x |

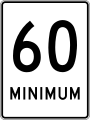

Minimum speed limits

Some roads also have minimum speed limits, usually where slow speeds can impede traffic flow or be dangerous. The use of minimum speed limits is not as common as maximum speed limits, since the risks of speed are less common at lower speeds.

Middle speed limits

Traffic rules limiting only middle speeds are rare. One such example exists on the ice roads in Estonia, where it is advised to avoid driving at the speed of 25–40 km/h (16–25 mph) as the vehicle may create resonance that may in turn induce the breaking of ice. This means that two sets of speeds are allowed: under 25 km/h (16 mph) and between 40–70 km/h (25–43 mph).

Variable speed limits

In Germany, the first known experiments with variable speed limit signs took place in 1965 on a 30 kilometer stretch of German motorway, the A8 between Munich and the border city of Salzburg, Austria. Mechanically variable message signs could display speeds of 60, 80 and 100 km/h, as well as text indicating a "danger zone" or "accident". Personnel monitored traffic using video technology and manually controlled the signage. Beginning in the 1970s, additional advanced traffic control systems were put into service. Modern motorway control systems can work without human intervention using various types of sensors to measure traffic flow and weather conditions. In 2009, 1,300 kilometers (810 miles) of German motorways were equipped with such systems.

In the United States, heavily traveled portions of the New Jersey Turnpike began using variable speed limit signs in combination with variable message signs in the late 1960s. Officials can adjust the speed limit according to weather, traffic conditions, and construction. More typically, variable speed limits are used on remote stretches of highway in the United States in areas with extreme changes in driving conditions. For example, variable limits were introduced in October 2010 on a 52-mile (84 km) stretch of Interstate 80 in Wyoming, replacing the winter season speed reduction from 75 to 65 mph (121 to 105 km/h) that had been in place since 2008. This Variable Speed Limit system has been proven effective in terms of reducing crash frequency and road closures. Similarly, Interstate 90 at Snoqualmie Pass and other mountain passes in Washington State have variable speed limits as to slow traffic in severe winter weather. As a response to fog-induced chain-reaction collisions involving 99 vehicles in 1990, a variable speed limit system covering 19 miles (31 km) of Interstate 75 in Tennessee was implemented in fog-prone areas around the Hiwassee River. The Georgia Department of Transportation installed variable speed limits on part of Interstate 285 around Atlanta in 2014. These speeds can be as low as 35 mph but are generally set to 65 mph. In 2016, the Oregon Department of Transportation installed a variable speed zone on a 30-mile stretch of Interstate 84 between Baker City and Ladd Canyon. The new electronic signs collect data regarding temperature, skid resistance, and average motorist speed to determine the most effective speed limit for the area before presenting the limit on the sign. This speed zone was scheduled to be activated November 2016. Ohio established variable speed limits on three highways in 2017, then in 2019 granted the authority to the Ohio Department of Transportation to establish variable limits on any of its highways.

In the United Kingdom, a variable speed limit was introduced on part of the M25 motorway in 1995, on the busiest 14-mile (23 km) section from junction 10 to 16. Initial results suggested savings in journey times, smoother-flowing traffic, and a decrease in the number of crashes; the scheme was made permanent in 1997. However, a 2004 National Audit Organisation report noted that the business case was unproved; conditions at the site of the Variable Speed Limits trial were not stable before or during the trial, and the study was deemed neither properly controlled nor reliable. Since December 2008 the upgraded section of the M1 between the M25 and Luton has had the capability for variable speed limits. In January 2010 temporary variable speed cameras on the M1 between J25 and J28 were made permanent.

New Zealand introduced variable speed limits in February 2001. The first installation was on the Ngauranga Gorge section of the dual carriageway on State Highway 1, characterized by steep terrain, numerous bends, high traffic volumes, and a higher than average accident rate. The speed limit is normally 80 km/h (50 mph).

Austria undertook a short-term experiment in 2006, with a variable limit configuration that could increase statutory limits under the most favorable conditions, as well as reduce them. In June 2006, a stretch of motorway was configured with variable speed limits that could increase the general Austrian motorway limit of 130 to 160 km/h (81 to 99 mph). Then Austrian Transport Minister Hubert Gorbach called the experiment "a milestone in European transport policy-despite all predictions to the contrary"; however, the experiment was discontinued.

Roads without speed limits

Just over half of the German autobahns have only an advisory speed limit (a Richtgeschwindigkeit), 15% have temporary speed limits due to weather or traffic conditions, and 33% have permanent speed limits, according to 2008 estimates. The advisory speed limit applies to any road in Germany outside of towns which is either a dual carriageway or features at least two lanes per direction, regardless of its classification (e.g. Autobahn, Federal Highway, State Road, etc.), unless there is a speed limit posted, although it is less common for non-autobahn roads to be unrestricted. All other roads in Germany outside of towns, regardless of classification, do have a general speed limit of 100 km/h, which is usually reduced to 80 km/h at Allée-streets (roads bordered by trees or bushes on one or both sites). Travel speeds are not regularly monitored in Germany; however, a 2008 report noted that on the autobahn in Niemegk (between Leipzig and Berlin) "significantly more than 60% of road users exceed 130 km/h (81 mph) [and] more than 30% of motorists exceed 150 km/h (93 mph)". Measurements from the state of Brandenburg in 2006 showed average speeds of 142 km/h (88 mph) on a 6-lane section of autobahn in free-flowing conditions.

Prior to German reunification in 1990, accident reduction programs in eastern German states were primarily focused on restrictive traffic regulation. Within two years of reunification, the availability of high-powered vehicles and a 54% increase in motorized traffic led to a doubling of annual traffic deaths, despite "interim arrangements [which] involved the continuation of the speed limit of 100 km/h (62 mph) on autobahns and of 80 km/h (50 mph) outside cities". An extensive program of the four Es (enforcement, education, engineering, and emergency response) brought the number of traffic deaths back to pre-unification levels after a decade of effort, while traffic regulations were conformed to western standards (e.g., 130 km/h (81 mph) freeway advisory limit, 100 km/h (62 mph) on other rural roads).

Rural roads on the Isle of Man have no speed limits on many rural roads; a 2004 proposal to introduce general speed limits of 60 mph and 70 mph on Mountain Road, for safety reasons, was not pursued following consultation. Measured travel speeds on the island are relatively low.

The Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana also do not have speed limits by default.

Roads formerly without speed limits

Many roads without a maximum limit became permanently limited following the 1973 oil crisis. For example, Switzerland and Austria had no maximum restriction prior to 1973 on motorways and rural roads, but imposed a temporary 100 km/h (62 mph) maximum limit in response to higher fuel prices; the limit on motorways was increased to 130 km/h (81 mph) later in 1974.

Montana and Nevada were the last remaining U.S. states relying exclusively on the basic rule, without a specific, numeric rural speed limit before the National Maximum Speed Law of 1974. After the repeal of federal speed mandates in 1996, Montana was the only state to revert to the basic rule for daylight rural speed regulation. The Montana Supreme Court ruled that the basic rule was too vague to allow citation, prosecution, and conviction of a driver; concluding enforcement was a violation of the due process requirement of the Montana Constitution. In response, Montana's legislature imposed a 75 mph (121 km/h) limit on rural freeways in 1999.

Australia's Northern Territory, had no rural speed limit until 2007, and again from 2014 to 2016. Sections of the Stuart Highway had no limits as part of an open speed limit trial.

Method

Several methods exist to set up a speed limit:

- Engineering

- Harm minimization

- Economic optimization

- Expert system

For instance, the Injury Minimization (known as Safe System) method takes into account the crash types that are likely to occur, the impact forces that result, and the tolerance of the human body to withstand these forces to set speed limit. This method is used in countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden.

The Operating speed method sets the maximum speed at or around the 85th percentile speed. This reduces the need to enforce the speed limit, but also allows drivers to fail to select the appropriate travel speed, when they misjudge the risk their environment induces. This is one method used in the United States of America.

Enforcement

Speed limit enforcement is the action taken by appropriately empowered authorities to check that road vehicles are complying with the speed limit. Methods used include roadside speed monitoring, set up and operated by the police, and automated roadside speed camera systems, which may incorporate the use of an automatic number plate recognition system.

In 2012, in the UK, 30% of drivers did not comply with speed limits.

In Europe, between 2009 and 2012, 20% of European drivers have been fined for excessive speed. In 2012, in Europe, 62% of people supported the idea of setting up speed-limiting devices, with adequate tolerance levels in order to limit driver confusion. One efficient scheme consists of penalty points and charges for speeding slightly over the speed limit.

Another possibility is to alter the roadway by implementing traffic calming measures, vehicle activated signs, or safety cameras.

The city of Munich has adopted self-explaining roads: roadway widths, intersection controls, and crossing types have been harmonized so that drivers assume the speed limit without a posted sign.

Justification

Speed limits are set primarily to balance road traffic safety concerns with the effect on travel time and mobility. Speed limits are also sometimes used to reduce consumption of fuel or in response to environmental concerns (e.g. to reduce vehicle emissions or fuel use). Some speed limits have also been initiated to reduce gas-oil imports during the 1973 oil crisis.

Road traffic safety

According to a 2004 report from the World Health Organization, 22% of all injury mortality worldwide was from road traffic injuries in 2002, and without "increased efforts and new initiatives" casualty rates would increase by 65% between 2000 and 2020. The report identified that the speed of vehicles was "at the core of the problem", and recommended that speed limits be set appropriately for the road function and design, along with the implementation of physical measures related to the road and the vehicle, and increased effective enforcement by the police. Road incidents are said to be the leading cause of deaths among children 10–19 years of age (260,000 children die a year; 10 million are injured).

Maximum speed limits place an upper limit on speed choice and, if obeyed, can reduce the differences in vehicle speeds by drivers using the same road at the same time. Traffic engineers observe that the likelihood of a crash happening is significantly higher if vehicles are traveling at speeds faster or slower than the mean speed of traffic; when severity is taken into account, the risk is lowest for those traveling at or below the median speed and "increases exponentially for motorists travelling much faster".

It is desirable to attempt to reduce the speed of road vehicles in some circumstances because the kinetic energy involved in a motor vehicle collision is proportional to the square of the speed at impact. The probability of a fatality is, for typical collision speeds, empirically correlated to the fourth power of the speed difference (depending on the type of collision, not necessarily the same as travel speed) at impact, rising much faster than kinetic energy.

- Kinetic energy

- Braking distance during danger

Typically motorways have higher speed limits than conventional roads because motorways have features which decrease the likelihood of collisions and the severity of impacts. For example, motorways separate opposing traffic and crossing traffic, employ traffic barriers, and prohibit the most vulnerable users such as pedestrians and bicyclists. Germany's crash experience illustrates the relative effectiveness of these strategies on crash severity: on autobahns 22 people died per 1,000 injury crashes, a lower rate than the 29 deaths per 1,000 injury accidents on conventional rural roads. However, the rural risk is five times higher than on urban roads; speeds are higher on rural roads and autobahns than urban roads, increasing the severity potential of a crash. The net effect of speed, crash probability, and impact mitigation strategies may be measured by the rate of deaths per billion-travel-kilometers: the autobahn fatality rate is 2 deaths per billion-travel-kilometers, lower than either the 8.7 rates on rural roads or the 5.3 rate in urban areas. The overall national fatality rate was 5.6, slightly higher than urban rate and more than twice that of autobahns.

The 2009 technical report An Analysis of Speeding-Related Crashes:Definitions and the Effects of Road Environments by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration showed that about 55% of all speeding-related crashes when fatal listed "exceeding posted speed limits" among their crash factors, and 45% had "driving too fast for conditions" among their crash factors. However, the authors of the report did not attempt to determine whether the factors were a crash cause, contributor, or an unrelated factor. Furthermore, separate research finds that only 1.6% of crashes are caused by drivers that exceed the posted speed limit. Finally, exceeding the posted limit may not be a remarkable factor in the crash analysis as there are roadways where virtually all motorists are in technical violation of the law.

The speed limit will also take note of the speed at which the road was designed to be driven (the design speed), which is defined in the US as "a selected speed used to determine the various geometric design features of the roadway". However, traffic engineers recognize that "operating speeds and even posted speed limits can be higher than design speeds without necessarily compromising safety" since design speed is "based on conservative assumptions about driver, vehicle and roadway characteristics".

Vision Zero, which envision reducing road fatalities and serious injuries to zero by 2020, suggests the following "possible long term maximum travel speeds related to the infrastructure, given best practice in vehicle design and 100% restraint use":

| Type of infrastructure and traffic | Possible travel speed (km/h) |

|---|---|

| Locations with possible conflicts between pedestrians and cars | 30 km/h (19 mph) |

| Intersections with possible side impacts between cars | 50 km/h (31 mph) |

| Roads with possible frontal impacts between cars, including rural roads | 70 km/h (43 mph) |

| Roads with no possibility of a side impact or frontal impact (only impact with the infrastructure) | 100 km/h (62 mph)+ |

"Roads with no possibility of a side impact or frontal impact" are sometimes designated as Type 1 (motorways/freeways/Autobahns), Type 2 ("2+2 roads"), or Type 3 ("2+1 roads"). These roadways have crash barriers separating opposing traffic, limited access, grade separation and prohibitions on slower and more vulnerable road users. Undivided rural roads can be quite dangerous even with speed limits that appear low by comparison. For example, in 2011, Germany's 100 km/h (62 mph)-limited rural roads had a fatality rate of 8.7 deaths per billion travel-km, over four times higher than the autobahn rate of 2 deaths. Autobahns accounted for 31% of German road travel in 2011, but just 11% (453 of 4,009) of traffic deaths.

In 2018, an IRTAD WG published a document which recommended maximum speed limits, taking into account forces the human body can tolerate and survive.

| Type of infrastructure and traffic | Possible travel speed (km/h) |

|---|---|

| Locations (built up areas) with possible conflicts between pedestrians and cars | 30 km/h (19 mph) or 40 km/h (25 mph) |

| Intersections with possible side impacts between cars | 50 km/h (31 mph) |

| rural roads without median barrier, with risk of head-on collisions | 70 km/h (43 mph) or 80 km/h (50 mph) |

| Source IRTAD, 2018 | |

Fuel efficiency

Fuel efficiency sometimes affects speed limit selection. The United States instituted a National Maximum Speed Law of 55 mph (89 km/h), as part of the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act, in response to the 1973 oil crisis to reduce fuel consumption. According to a report published in 1986 by The Heritage Foundation, a Conservative advocacy group, the law was widely disregarded by motorists and hardly reduced consumption at all. In 2009, the American Trucking Associations called for a 65 mph speed limit, and also national fuel economy standards, claiming that the lower speed limit was not effective at saving fuel.

Environmental considerations

Speed limits can also be used to improve local air quality issues or other factors affecting environmental quality (e.g. the "environmental speed limits" in an area of Texas). The European Union is also increasingly using speed limits as in response to environmental concerns. European studies have stated that, whereas the effects of specific speed reduction schemes on particulate emissions from trucks are ambiguous, lower maximums speed for trucks consistently result in lower emissions of CO2 and better fuel efficiency.

Advocacy

Speed limits, and especially some of the methods used to attempt to enforce them, have always been controversial. A variety of organisations and individuals either oppose or support the use of speed limits and their enforcement.

Opposition

Speed limits and their enforcement have been opposed by various groups and for various reasons since their inception. In the UK, the Motorists' Mutual Association (est. 1905) was formed initially to warn members about speed traps; the organisation would go on to become the AA.

More recently, advocacy groups seek to have certain speed limits as well as other measures removed. For example, automated camera enforcement has been criticised by motoring advocacy groups including the Association of British Drivers, and the German Auto Club (ADAC).

Arguments used by those advocating a relaxation of speed limits or their removal include:

- A 1994 peer-reviewed paper by Charles A. Lave et al. titled Did the 65 mph Speed Limit Save Lives? which states as evidence that a higher speed limit may create a positive shift in traffic to designated safer roads.

- A 1998 report in the Wall Street Journal titled "Highways are safe at any speed", stating when speed limits are set artificially low, tailgating, weaving and speed variance (the problem of some cars traveling significantly faster than others) make roads less safe.

- A 2007 ePetition to the UK government calling for speed cameras to be scrapped on the basis that the benefits were exaggerated and that they may actually increase casualty levels, conducted by Safe Speed, a UK advocacy organisation campaigning for higher speed limits, which received over 25,000 signatures.

- A 2008 declaration by the German Automobile Manufacturer's Association calling general limits "patronizing," arguing instead for variable speed limits. The Association also stated that "raising the speed limits in Denmark (in 2004 from 110 km/h to 130 km/h) and Italy (2003 increase on six-lane highways from 130 km/h to 150 km/h) had no negative impact on traffic safety. The number of accidental deaths even declined".

- In a 2010 ADAC report, it was said that an autobahn speed limit was unnecessary because numerous countries with a general highway speed limit had worse safety records than Germany. However, more recent data show that Germany ranks in the lower middle field in a Europe-wide comparison regarding the number of fatalities per billion vehicle kilometers traveled on motorways. ETSC considers that those data are not comparable, because estimations of the number of kilometers traveled are not estimated the same way in different countries. Since 2020, the ADAC is „nicht mehr grundsätzlich“ ("no longer in principle") against a speed limit on autobahns.

Signage

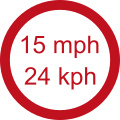

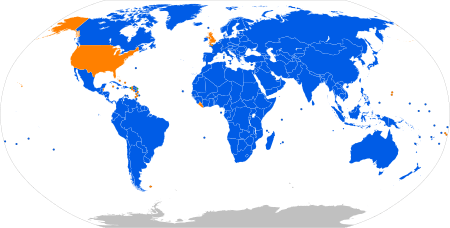

Most countries worldwide measure speed limits in kilometres per hour, while the United Kingdom, United States, and several smaller countries measure speed limits in miles per hour instead. Signs in Samoa display both units simultaneously.

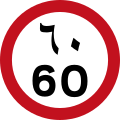

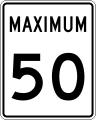

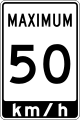

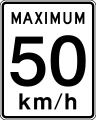

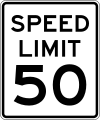

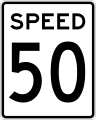

There are two basic designs for speed limit signs: the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals specifies a white or yellow circle with a red border, while the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) published by the United States Federal Highway Administration specifies a white rectangle with the legend SPEED LIMIT. Vienna-style speed limit signs originated in Europe and are used in most of the world, including many countries that otherwise follow the MUTCD. Variations on the MUTCD design are used in Canada, Guam, Liberia, Puerto Rico, the United States, the U.S. Virgin Islands. Australia also used a variation on the MUTCD design until the country metricated in 1974.

In most of the United States, speed limit signs bear the words SPEED LIMIT above the numeric speed limit, as specified in the MUTCD. However, in Alaska and California, speed limits are often labeled MAXIMUM SPEED instead. In Oregon, most speed limit signs are simply labeled SPEED. Canada has similar signs bearing the legend MAXIMUM, which has a similar meaning in English and French, the country's two main languages. Signs in Australia (since metrication in 1974), Mexico, Panama, and Peru are rectangular but inscribe the numeric limit within a red circle like on Vienna Convention signs. The MUTCD formerly specified an optional metric design that included the words SPEED LIMIT and the numeric limit inscribed within a black circle, though it was rarely used in the United States; this design is still occasionally found in Liberia.

In the European Union, large signposts showing the national (maximum) speed limits of the respective country are usually erected immediately after border crossings, with a repeater sign some 200 to 500 m (660 to 1,640 ft) after the first. Some places provide an additional "speed zone ahead" ahead of the restriction, and speed limit reminder signs may appear at regular intervals, which may be painted on the road surface.

In Ontario, the type, location, and frequency of speed limit signs are covered by regulation 615 of the Ontario Highway Traffic Act.

Maximum speed limit

-

UK sign for 50 mph

-

Ireland includes the text "km/h" since going metric in 2005

-

Japan uses blue numerals; km/h

-

Samoa uses both miles per hour and kilometres per hour

-

The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia (km/h) use both Western Arabic and Eastern Arabic numerals

-

Canada (displayed in km/h; All speed limit signs are MUTCD style)

-

Canada (Ontario)

-

Canada (Yukon and British Columbia)

-

United States (in mph)

-

United States (Oregon variant)

-

United States (New York variant; "CITY", "VILLAGE", "TOWN", or a variant of the word "AREA" can be used in place of "STATE")

Some speed limits are applicable to a zone.

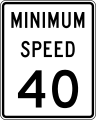

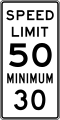

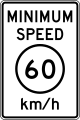

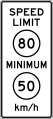

Minimum speed limit

Minimum speed limits are often expressed with signs using blue circles, based on the obligatory sign specifications of the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals. In the United States of America, minimum speed limit signs are identical to their respective maximum speed limit signs, with SPEED LIMIT replaced with MINIMUM SPEED. Some South American countries (e.g.: Argentina) use a red border. Japan and South Korea use their normal speed limit sign, with a line below the limit.

-

The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia (km/h) use both Western Arabic and Eastern Arabic numerals

-

Argentina, km/h

-

Chile; km/h

-

Colombia; km/h

-

Indonesia (includes the text "km" on the top right corner); km/h

-

Japan; km/h

-

Philippines; km/h

-

South Korea (which looks similar to this sign from Japan except the numerals are black); km/h

-

United States; mph

Special speed limits

In some countries, speed limits may apply to certain classes of vehicles or special conditions such as night-time. Usually, these speed limits will be reduced from the normal limit for safety reasons.

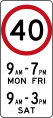

-

Australia - Speed limit during certain times

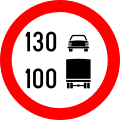

-

Romania - Trucks speed limit

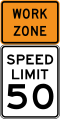

-

United States - Roadworks zone speed limit

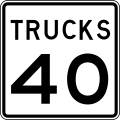

-

Unique speed limit sign in the United States on evacuation routes requiring drivers to maintain the maximum safe speed

-

Safe speed sign in South Korea

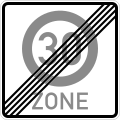

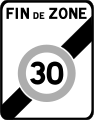

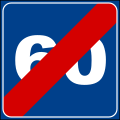

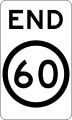

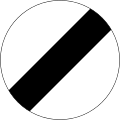

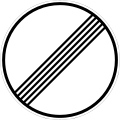

Speed limit derestriction

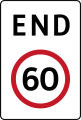

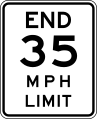

In some countries, derestriction signs are used to mark where a speed zone ends. The speed limit beyond the sign is the prevailing limit for the general area; for example, the sign might be used to show the end of an urban area. In the United Kingdom, the sign means that the national speed limit applies (60 mph on open roads and 70 mph on dual carriageways and motorways). In New Zealand it means you are on an open road, but the maximum legal speed of 100 km/h still applies. On roads without general speed limits, such as the German Autobahn, a portion of the Stuart Highway, and rural areas on the Isle of Man, it means the end of all quantitative speed limits.

-

Australia, now relatively rare

-

Belgium, United Kingdom, Ireland pre-2005, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia and Switzerland

-

End speed limit 35 mph United States

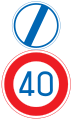

Advisory speed limit

Advisory speed limits may provide a safe suggested speed in an area, or warn of the maximum safe speed for dangerous curves.

In Germany, an advisory speed limit may be combined with a traffic signal to recommend the speed at which drivers should drive to reach the next light at its green phase, thereby avoiding a stop.

Technology

Some European cars include in-vehicle systems that support drivers’ compliance with the speed limit, known as intelligent speed adaptation (ISA). ISA supports drivers in complying with the speed limit in various parts of the network, while speed limiters for heavy goods vehicles and coaches only govern the maximum speed. These systems have positive effects on speed behaviour, and improve safety. A speed-limiting device, such as ISA are considered useful by 25% of European car drivers. In 2019, Google Maps integrated alerts for speed traps within its application, along with audible alerts for nearby speed cameras. The technology was first developed by Waze, with requests for it to be removed from the application by police officers.

See also

In Spanish: Límites de velocidad para niños

In Spanish: Límites de velocidad para niños