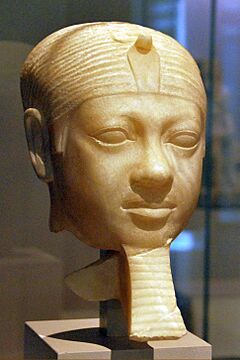

Shepseskaf facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Shepseskaf |

|

|---|---|

| Shepseskhaf, Sebercherês, Σεβερχέρης, Severkeris | |

Shepseskaf's cartouche on the Abydos King List

|

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | Duration uncertain, probably four years but possibly up to seven, in the late 26th to mid-25th century BC (fourth dynasty) |

| Predecessor | Menkaure |

| Successor | Userkaf (most probably) or Thamphthis |

| Consort | Uncertain; Khentkaus I or Bunefer |

| Children | Possibly Bunefer (♀), conjecturally Userkaf (♂) |

| Father | Menkaure (uncertain) |

| Mother | Uncertain; Khamerernebty II, Rekhetre, Khentkaus I or Neferhetepes |

| Burial | Mastabat al-Fir'aun |

| Monuments | Completion of the temple complex of Menkaure's pyramid, mastabat al-Fir'aun |

Shepseskaf (meaning "His Ka is noble") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt, the sixth and probably last ruler of the fourth dynasty during the Old Kingdom period. He reigned most probably for four but possibly up to seven years in the late 26th to mid-25th century BC.

Shepseskaf's relation to his predecessor Menkaure is not entirely certain; he might have been his son or possibly his brother. The identity of his mother is highly uncertain as she could have been one of Menkaure's consorts or queen Khentkaus I or Neferhetepes. Similarly, Shepseskaf's relation to his probable successor on the throne, Userkaf, is not known although in the absence of clear indication of strife at the transition between the fourth and fifth dynasties, Userkaf could well have been his son or his brother. If Shepseskaf was succeeded directly by Userkaf rather than by Thampthis as claimed by some historical sources, then his death marks the end of the fourth dynasty. The transition to the fifth dynasty seems not to have been a sharp rupture but rather a continuous process of evolution in the king's power and role within the Egyptian state. Around this time, some of the highest positions of power such as that of vizier which had hitherto been the prerogative of the royal family were opened to nobles of non-royal extraction.

The only activities firmly datable to Shepseskaf's short reign are the completion of the hitherto unfinished mortuary complex of the Pyramid of Menkaure using mudbricks and the construction of his own tomb at South Saqqara, now known as the Mastabat al-Fir'aun. Shepseskaf's decisions to abandon the Giza necropolis and to build a mastaba, that is a flat-roofed rectangular structure, rather than a pyramid for himself are significant and continue to be debated. Some Egyptologists see these decisions as symptoms of a power-struggle between the king and the priesthood of Ra, while others believe purely practical considerations, possibly including a declining economy, are at fault. Alternatively, it may be that Shepseskaf intended his tomb to be a pyramid, but after his death it was completed as a mastaba. Possibly because of this, and the small dimensions of his tomb compared to those of his forebears and his short reign, Shepseskaf was the object of a relatively minor state-sponsored funerary cult that disappeared in the second half of the fifth dynasty. This cult was revived in the later Middle Kingdom period as a privately run lucrative cult aimed at guaranteeing a royal intercessor for the offerings made to their dead by members of the lower strata of society.

Contents

Family

Parents

The relationship between Shepseskaf and his predecessor Menkaure is not entirely certain. The dominant view in modern Egyptology was first expounded by George Andrew Reisner who proposed that Shepseskaf was Menkaure's son. Reisner based his hypothesis on a decree showing that Shepseskaf completed Menkaure's mortuary temple. This hypothesis is shared by many Egyptologists including Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, Rainer Stadelmann and Peter Clayton. Peter Jánosi nonetheless remarks that the decree does not constitute irrefutable proof of filiation since it does not describe the relationship between these two kings explicitly. In particular, the completion of the tomb of a deceased pharaoh by his successor does not necessarily depend on a direct father/son relation between the two. A possible alternative proposed by Miroslav Verner is that Menkaure and Shepseskaf could have been brothers, and the latter's consequently advanced age when ascending to the throne could explain his short reign. In contrast with these hypotheses, Egyptologists Ludwig Borchardt and William C. Hayes posited that Shepseskaf could have been of non-royal extraction and took the throne only thanks to his marriage to queen Khentkaus I.

The identity of Shepseskaf's mother is even more uncertain than that of his father. If the latter was Menkaure, then Shepseskaf's mother could have been one of Menkaure's royal wives Khamerernebty II, Rekhetre or a secondary wife. Alternatively Miroslav Bárta believes that Khentkaus I may have been Shepseskaf's mother and also the mother of his successor Userkaf. Indeed, a close relationship between Shepseskaf and Khentkaus I has been inferred by Egyptologist Selim Hassan based on the "immense conformity" of their tombs, an opinion that is widely shared, yet what this relationship was remains unclear. Khentkaus I may instead have been the wife or the daughter of Shepseskaf. One more possibility was put forth by Arielle Kozloff, who proposed instead that it was Neferhetepes, a daughter of Djedefre, who was Shepseskaf's mother. For Egyptologist Vivienne Gae Callender there is no evidence in support of this hypothesis.

Queens and children

Inscriptions in queen Bunefer's Giza tomb demonstrate that she is related to Shepseskaf: she notably bore the title of "Great of praise, priestess of King Shepseskaf, the king's wife, the great ornament, the great favourite". Lana Troy, an Egyptologist, deduces from this title that while she married a pharaoh, she served as a priestess in the funerary cult for her father and therefore must have been Shepseskaf's daughter and the consort of another unspecified king. Indeed, all priestesses serving in a king's funerary cult were princesses, daughters or granddaughters of that king. If this hypothesis is true, it makes Bunefer the only queen known from Ancient Egypt to have served in a mortuary cult. Exceptional circumstances could explain this observation, for example if there was no other suitable female descendant to officiate in Shepseskaf's cult after his death. Bunefer's mother could have been Khentkaus I whose tomb is located near Bunefer's so that Khentkaus I might have been a consort of Shepseskaf. Bunefer's royal husband may have been pharaoh Thamphthis, whose existence is uncertain however as he is not attested archaeologically (see below for a discussion).

Hassan, who excavated Bunefer's tomb, rejects the opinion that Bunefer was Shepseskaf's daughter. He notes that most of Bunefer's titles are wifely ones and stresses "the fact that the name of Shepseskaf appears in her tomb is in favour of the assumption that he was her husband". In any case Bunefer had at least one son, whose name is lost, and whose father was not a king according to this son's titles. He was possibly an issue from a second, non-royal, marriage of Bunefer.

Princess Khamaat married to the high priest of Ptah, Ptahshepses, and is known by her titles to have been the daughter of a king. She was long thought to be a daughter of Shepseskaf following a hypothesis by 19th-century Egyptologist Emmanuel de Rougé. A consensus was reached on this issue, but in 2002 Egyptologist Peter F. Dorman published inscriptions from Ptahshepses's tomb showing that she was Userkaf's daughter instead.

Finally, Mark Lehner proposes that Shepseskaf fathered pharaoh Userkaf with queen Khentkaus I, an idea shared by Kozloff but rejected by Bárta who thinks they were brothers. Alternatively, Khentkaus I has been conjectured to be Shepseskaf's daughter.

Reign

Shepseskaf's reign is difficult to date precisely in absolute terms. An absolute chronology referring to dates in the modern Western calendar is estimated by Egyptologists working backwards by adding reign lengths – themselves uncertain and inferred from historical sources and archaeological evidence – and, in a few cases, using ancient astronomical observations and radiocarbon dates. These methodologies do not agree perfectly and some uncertainty remains. As a result, Shepseskaf's rule is dated to some time around the late 26th to mid-25th century BC.

Relative chronology

The relative chronological position of Shepseskaf within the fourth dynasty is not entirely certain. The near contemporary fifth dynasty royal annals now known as the Palermo stone indicates unambiguously that he succeeded Menkaure on the throne and was crowned on the 11th day of the fourth month. The identity of his successor is less certain. Archaeological evidence seems to indicate that Shepseskaf was succeeded directly by Userkaf. In particular, no intervening king is mentioned on the tombs of officials who served at the time. For example, an inscription in the tomb of the palace courtier Netjerpunesut gives the following sequence of kings he served under: Djedefre → Khafre → Menkaure → Shepseskaf → Userkaf → Sahure → Neferirkare. Similarly, in his Giza tomb prince Sekhemkare reports about his career under the kings Khafre, Menkaura, Shepseskaf, Userkaf and Sahure, while the high priest Ptahshepses describes being born under Menkaure, growing up under Shepseskaf and starting his career under Userkaf. Furthermore, Egyptologist Patrick O'Mara underlines that "no names of estates of the period [which are] compounded with royal names make mention of any other kings than these, nor do the names of [...] royal grandchildren, who often bore the name of a royal ancestor as a component of their own [name]." This reconstruction of late fourth to early fifth dynasty is also in agreement with that given on the Abydos king list written during the reigns of Seti I (c. 1292–1279 BC), where Shepseskaf's cartouche is on the 25th entry between those of Menkaure and Userkaf.

Three historical sources go directly or indirectly against this order of succession. The source in direct contradiction is the Aegyptiaca (Αἰγυπτιακά), a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BC) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. According to the Byzantine scholar George Syncellus, Africanus wrote that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Bicheris → Sebercherês → Thamphthis" at the end of the fourth dynasty while "Usercherês" is given as the fifth dynasty's first king. Sebercherês (in Greek, Σεβερχέρης) and Usercherês are believed to be the Hellenised forms for Shepeseskaf and Userkaf, respectively, while the identities of Bicheris and Thampthis are unknown. They could refer to shadowy figures, perhaps the fourth dynasty prince Baka in the case of Bicheris and Thampthis could originate from the Egyptian name Djedefptah, or they could both be fictitious rulers. That a king might have reigned between Shepseskaf and Userkaf is also indirectly supported by the Turin canon, a king list written during the 19th dynasty in the early Ramesside era (1292–1189 BC). The canon, written on papyrus is damaged at several spots and thus many royal names are either fragmentary or completely lost in lacunae today. In column III, line 15 King Shepseskaf is listed, line 16 is wholly in a lacuna while the end of Userkaf's name is legible on line 17. The missing line 16 must have originally held the royal name of Shepseskaf's unknown successor. The Saqqara Tablet, written under Ramses II (c. 1303–1213 BC), also seems to have mentioned an unknown successor for Shepseskaf as it originally listed nine cartouches corresponding to fourth dynasty kings, when only six are otherwise known from archaeological evidence (Sneferu, Khufu, Djedefre, Khafra, Menkaure and Shepseskaf). The five cartouches between those of Khafre and Userkaf are now illegible.

For Egyptologist Nigel Strudwick, the uncertainty regarding Shepseskaf's successor and the presence of further shadowy rulers in historical sources during the late fourth dynasty point to some family instability at the time.

Duration

The duration of Shepseskaf's rule is uncertain but it is generally taken to have lasted probably four but perhaps up to seven years. Explicit archaeological evidence on this matter is reduced to six documents. Four of these are inscriptions dated to the year of his accession to the throne, three found in tombs of the Giza necropolis and one from the Palermo stone. The last two contemporary inscriptions mention his second regnal year, one of which is found on the decree of Shepseskaf concerning Menkaure's pyramid town.

Two historical sources report the duration of Shepseskaf's reign. The Turin canon credits him with a reign of four years, while Manetho's Aegyptiaca gives him seven years on the throne. Although this figure is compatible with the Palermo stone which may have had up to seven compartments relating Shepseskaf's reign according to Georges Daressy, this is considered an overestimate according to modern consensus. Verner points notably to the unfinished state of his mastaba to conclude Shepseskaf's rule did not exceed the four years attributed to him by the Turin canon. A reappraisal of the Palermo stone by Jürgen von Beckerath limits the space available on it for Shepseskaf's rule to five or six compartments, corresponding to that many years. Manetho's count may be explained by a conflation of the four full years attributed to Shepseskaf by the Turin king list plus two full years and a significant monthly fraction credited to his anonymous successor on that list. This successor could correspond to Manetho's Thampthis, to whom Manetho gives nine years of reign, although as observed by Verner archaeological evidence for this ruler is nil.

Activities

Very few activities of Shepseskaf are known. The Palermo stone reports that in the year of his accession to the throne he participated in the "going around the Two Lands" and a "festival of the diadem" during which two images of the god Wepwawet were fashioned and the gods who unite the two lands are said to have followed the king. These events occurred at or close to the coronation of the king. The site of Shepseskaf's tomb, said to be a pyramid, was chosen that same year. On that occasion, an enclosure of Lebanese wood may have been set up to surround the perimeter of the part of the Saqqara necropolis where the tomb was to be constructed. Finally Shepseskaf probably decreed a daily offering of 20 measures of something (what was offered is lost in a lacuna of the stone) to the senuti shrine.

It was during his second year of rule that Shepseskaf recorded the earliest surviving decree from the Old Kingdom period. Inscribed on a limestone slab uncovered in Menkaure's mortuary temple, the decree concerns the completion of this temple, records offerings to be made there and protects the estate and staff of the pyramid of Menkaure by exempting them from taxation:

Horus Shepsesket, the year after the first occasion of the count of cattle and herds [...] which was done in the presence of the King himself. The King of Upper and Lower Egypt Shepseskaf. For the king of Upper and Lower Egypt [Menkaure] he set up a monument, a pekher offering [...] in the pyramid of Menkaure [...] With regard to the pekher offering brought for the king of Upper and Lower Egypt [Menkaure] [...] priestly duty [is done] with respect to it for ever. [...] [it should never be taken away by someone] in the course of his duty for ever [...] the pyramid of Menkaure [...]. My majesty does not permit [...] servants [...] priests [...]

Excavations of Menkaure's mortuary temple confirm that it was probably left unfinished at this pharaoh's death. Originally planned to be made of granite, then altered to be completed of white Turah limestone, all stone construction ceased and the temple was hastily finished in crude bricks during Shepseskaf's rule. This material allows for rapid construction. Shepseskaf's works concerned the causeway and entrance corridors of the temple, its great open court, storerooms and inner temple as well as the exterior walls. All brick constructions were covered in yellow mud then plastered white and left plain, except for the walls of the great open court which were made into a system of niches. The completed doorways were fitted with wooden doors and the temple floors were of beaten mud on packed limestone chips, while the great court received a stone flooring.

Further activities are reported in Herodotus' account of the late fourth dynasty. According to Herodotus, Menkaure was succeeded by a king, whom he calls Asukhis, who built an outer court of Hephaestus's (Ptah's) temple, decreed a new law on borrowing to remedy the lack of money in circulation during his reign and built a brick pyramid. Herodotus's account cannot easily be reconciled with the historical reality and seems to stem from confusion between fourth and 24th dynasty rulers, garbled references to legends regarding a second dynasty king as lawgiver and 12th dynasty brick pyramids of Dahshur, such as that of Amenemhat III. As Diodorus Siculus makes similar mistakes in reporting the history of the fourth dynasty – notably, both he and Herodotus incorrectly believed the fourth dynasty came after the 20th – it is possible that it was their sources in Egypt which were at fault.

Court life

Some of the officials who served under Shepseskaf are known from the funerary inscriptions they made on their tombs and which mention the king. These are mostly found in Giza and Saqqara. The fact that many of these inscriptions only mention Shepseskaf without further details hints at the short duration of his reign. The court officials who mentioned Shepseskaf include Babaef II, vizier under Shepseskaf and possibly his cousin; Sekhemkare, a son of Khafre, priest of the royal funerary cults; Nisutpunetjer, who was a priest of the royal funerary cults; Ptahshepses I who was educated among the royal children in Shepseskaf's palace and harem, later promoted to the office of priest of Ptah by Userkaf and son-in-law of this pharaoh; and Kaunisut, a palace official, priest and director of hairdressers.

End of dynasty

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's Aegyptiaca, intended to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt. The historical reality of these dynasties is difficult to appraise and they might not correspond to the modern conception for that term: for example Djoser, the first king of the third dynasty, was the son of Khasekhemwy, final king of the Second dynasty. Stadelmann and Bárta remark that Shepseskaf (which means "His Ka is noble") and Userkaf have much in common, for example their throne names both follow the same pattern qualifying the Ka of Ra as "noble" for the former and "strong" for the later and they probably belonged to the same family with Userkaf being either Shepseskaf's son or his brother. In addition, the biographies of officials serving at the time show no break in their careers at the juncture of the fourth and fifth dynasties and no traces of religious, political or economic upheavals at the time.

Some distinction between the fourth and fifth dynasties may nonetheless have been recognised by the ancient Egyptians, as recorded by a tradition much older than Manetho's and found in the tale of the Westcar Papyrus. In this story, King Khufu is foretold the demise of his line and the rise of a new dynasty through the accession of three sons of Ra to the throne of Egypt.

In modern Egyptology no sharp division is understood to have taken place between the fourth and fifth dynasties. Yet some transition between them is perceived through the evolution of the Egyptian state at the time, from one where all power and positions of prestige were taken by the royal family, to one where the state-administration was opened to people of non-royal descent. It is in the interval from Menkaure to Userkaf that the royal family began to step back from the highest offices, in particular that of the vizier. Shepseskaf, Userkaf and their fifth dynasty successors responded to these changes by designing new means of asserting their supremacy and religious influence, through the cult of Ra, the creation of novel offices of state and changes in the king's role. Ra's primacy over the rest of the Egyptian pantheon and the increased royal devotion given to him made Ra a sort of state-god, a novelty in comparison with the earlier fourth dynasty, when more emphasis was put on royal burials.

Burial

Shepseskaf's tomb is a great mastaba at South Saqqara. Called Qbḥ-Špss-k3.f ("Qebeh Shepseskaf") by the ancient Egyptians, this name is variously translated as "Shepseskaf is pure", "Shepseskaf is purified", "Coolness of King Shepseskaf" and "The cool place of Shepseskaf". Nowadays it is known as Mastabat al-Fir'aun, meaning "bench of the pharaoh" in Egyptian Arabic. This mastaba was first recognised as such by Richard Lepsius who listed it as structure XLIII in his pioneering list of pyramids. First excavated in 1858 by Auguste Mariette, it was not before the years 1924–1925 that the mastaba was thoroughly explored by Gustave Jéquier.

Location

Shepseskaf's decision to be buried in South Saqqara represents a departure from the Giza necropolis used by his predecessors. The reason for this choice is debated. Verner remarks that this choice had political symbolism as it allowed Shepseskaf a greater proximity to the dynasty founder Sneferu's red and bent pyramids in Dahshur, possibly emphasising his belonging to the dynastic line. For Bárta, Shepseskaf simply decided to come back to the traditional burial grounds of Saqqara and Abusir, a choice that therefore does not need to be seen as a sign of religious conflicts within the royal family, as had been proposed by Hassan.

However, the main reason might have been economic or practical rather than political or religious. There was simply not enough space left in Giza for another large pyramid complex, and the proximity of limestone quarries to South Saqqara could have played a role. Egyptologist Adolf Erman instead conjectures that the choice of location for a pharaoh's tomb was mostly dictated by the vicinity of his palace which could change owing to economic, political and military interests. This remains unverified as no palace of an Old Kingdom king has been located so far, and it may be instead that it was the centre of the administration and royal house which followed the funerary complex rather than the other way around.

Decision to build a mastaba

As Shepseskaf chose to have a mastaba built for himself he broke with the fourth dynasty tradition of constructing pyramids. Several theories have been put forth to explain this choice. First, Verner hypothesises that Shepseskaf may have designed a mastaba as a temporary measure because he was faced with the arduous task of completing Menkaure's pyramid complex at Giza while simultaneously having to start his own tomb. In this theory, Shepseskaf may have intended to turn the mastaba into a pyramid at a later stage. In support of this theory is the observation that the architecture and layout of the subterranean structures of the mastaba exactly follow the standard plan for royal pyramids. Shepseskaf might have been forced to take this decision if Egypt experienced economic difficulties at the time as Verner posits, or perhaps Menkaure's failure to complete his mortuary temple could have made Shepseskaf more cautious about his own tomb.

At the opposite, Egyptologist Stephen Quirke believes that Shepseskaf's tomb amounts to the first step of a planned step pyramid that was unfinished owing to its owner's early death, only to be completed by his successor or his queen in the shape of a mastaba. This theory finds some support in the Palermo stone which indicates that the emplacement and name of Shepseskaf's tomb were chosen during his first year on the throne. In this text the name of the tomb is written with the determinative of a pyramid rather than that of a mastaba, but in the tomb of Nikauhor, who worked as overseer of Shepseskaf's tomb, it appears with the determinative of a mastaba.

Alternatively, Hassan has put forward the idea that Shepseskaf may have deliberately chosen to build a mastaba owing to religio-political reasons, as the pyramid shape is closely associated with the solar cult. In doing so he would have tried to undermine the growing influence of the priesthood of Ra. This hypothesis could also explain the absence of a direct theophoric reference to Ra in his name as well as in that of his probable immediate successor Userkaf. Hassan, who believes Khentkaus I was Shepseskaf's consort, further conjectures that Khentkaus was forced to marry Userkaf, the high priest of Ra, after Shepseskaf's death. This marriage would have sealed the unrivalled ascendancy of the solar cult throughout the fifth dynasty. Egyptologist Jaromir Málek concurs in part with this hypothesis, seeing Shepseskaf's decision as the symptom of a possible religious crisis. The archaeologist Joyce Tyldesley notes that if Shepseskaf really did intend his tomb to be a mastaba and regardless of his motivations, this indicates that while a pyramid may be desirable, it was not an absolute necessity for a pharaoh to reach the afterlife.

In a fourth opinion, Bárta, who stresses that the reasons for Shepseskaf's choice largely elude us, nonetheless proposes that the king may have lacked full legitimacy after ascending the throne from his position of high official through marriage. In this hypothesis Shepseskaf would be a son of Khentkaus I. While in all probability related to the fourth dynasty royal family, he may not have had the legitimacy that prince Khuenre, the firstborn son of Menkaure and queen Khamerernebty II, had enjoyed prior to his death. Possibly faced with opponents and a state-administration increasingly from outside of the royal family, he could have chosen to build a non-typical tomb fitting his peculiar status.

Architecture

The mastaba, oriented on a north–south axis, is rectangular in shape with a base of 99.6 m × 74.4 m (327 ft × 244 ft) and a height of 18 m (59 ft). The outer slope of its wall is 65° or 70° and it may have risen in two steps. The tomb dimensions are deemed very small and modest by Verner as compared with the great pyramids of Shepseskaf's fourth dynasty predecessors. Indeed, the total volume of the mastaba masonry represents no more than a third that of Menkaure's pyramid. For Verner and Egyptologist Abeer El-Shahawy, this could be explained by the decline in the economic prosperity of Egypt at the time as well as a decline in the king's power. At the opposite, for Stadelmann one should not conclude that political instability or economic difficulties prevented Menkaure, Shepseskaf and their successors from emulating the great pyramids of their forebears. Instead he proposes that the main impetus behind Menkaure's smaller pyramid and for Shepseskaf's decision to have a mastaba made for himself is a cultic change, where the pyramid is replaced as the centre of appearance and importance by the mortuary temple as the centre of the funerary ritual. In spite of its reduced size, Shepseskaf's tomb and funerary complex were probably unfinished at the death of the king, something which is taken to confirm a short reign. Excavations have shown that parts of the associated mortuary temple as well as the entirety of the causeway leading to it from the Nile valley have been "hastily" completed in mudbrick, probably by one of his successors.

The narrow ends of the mastaba were deliberately raised unlike the traditional fashion, making the tomb look like a great sarcophagus or the hieroglyphic determinative for a shrine. The mastaba was originally clad with white Turah limestone except for its lower course, which was clad in red granite. The entrance to the substructures is on the mastaba's northern face, from where a nearly 20.95 m (68.7 ft) long rock-cut passageway descends at 23°30' to an antechamber, the access to which was to be protected by three portcullises. To the southeast of the antechamber is a room with six niches, possibly storerooms, while west of the antechamber lies the burial chamber. Measuring 7.79 m × 3.85 m (25.6 ft × 12.6 ft) it is lined with granite and has a 4.9 m (16 ft) high arched ceiling sculpted into a false vault. Remnants of a decorated dark basalt sarcophagus were uncovered there although the burial chamber was never finished and in all probability never used.

The mastaba was surrounded by a double enclosure wall of mudbricks. On the eastern face of the tomb was a mortuary temple with an offering hall, false door and five storerooms, the layout of which later served as template for Neferirkare Kakai's temple. No niches meant to house statues of the king were found, although fragments of a statue of Shepseskaf in the style of those of Khafre and Menkaure were uncovered in the temple. To the east lay a small inner court and a larger outer one. Remnants of a causeway have been found; it is supposed to have led to a valley temple which has yet to be located.

Legacy

Old Kingdom

Like other pharaohs of the fourth and fifth dynasties, Shepseskaf was the object of an official funerary cult after his death. This cult seems to have been relatively minor when compared to those given to his predecessors. Only three priests serving in this cult are known, including Shepseskaf's probable daughter queen Bunefer. This contrasts with the at least 73 and 21 priests known to have served in the cults of Khufu and Menkaure, respectively. Furthermore, no evidence for Shepseskaf's cult has been found beyond the mid fifth dynasty, while the cults of some of his close successors lasted beyond the end of the Old Kingdom. Provisions for these official mortuary cults were produced in agricultural estates set up during the ruler's reign. Possibly owing to the short duration of his reign only two such estates are known for Shepseskaf compared with at least sixty for Khufu.

In parallel to the official cult, it seems that Shepseskaf's name and memory were especially well regarded at least as late as the second half of the fifth dynasty as attested by at least seven high officials bearing the name Shepseskafankh, meaning "May Shepseskaf live" or "Shepseskaf lives", up until the reign of Nyuserre Ini. This includes a royal physician, a royal estate steward, a courtier, a priest, and a judicial official.

Middle Kingdom

While no trace of state-sponsored cult of Shepseskaf have been uncovered from the late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate periods, Jéquier discovered a Middle Kingdom stele during his excavations of Shepseskaf's mortuary temple. At that time, the vicinity of the mastaba had become a necropolis housing tombs from the lower strata of society. The stele uncovered by Jéquier probably originated from a nearby tomb and had been reused at a later time as paving for the temple floor. The stele indicates that some sort of popular cult had been revived by the 12th dynasty on the premises of the temple. Dedicated by a butcher named Ptahhotep, the stele depicts Ptahhotep and his family seemingly officiating a fully functioning cult, with its priests, scribes and servants. Contrary to the Old Kingdom state-sponsored cult honouring Shepseskaf, the main object of this cult was not Shepseskaf himself but the dead of the surrounding necropolis for whom people were making offerings, offerings which only the gods could give the dead after accepting them thanks to Shepseskaf's intercession. For Jéquier, this cult had been turned into a lucrative activity by Ptahhotep's family.

New Kingdom

Along with other royal monuments at Saqqara and Abusir which had fallen into ruin, Shepseskaf's mastaba was the object of restoration works under the impulse of prince Khaemwaset, a son of Ramses II. This was possibly to appropriate stones for his father's construction projects while ensuring a minimal restoration for cultic purposes.