Rwandan genocide facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rwandan genocide |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Rwandan Civil War | |

Rwandan Genocide Memorial, Geneva

|

|

| Location | Rwanda |

| Date | 7 April – 15 July 1994 |

| Target | Tutsi population and moderate Hutus |

|

Attack type

|

Genocide, mass murder |

| Deaths | Estimated: 491,000–800,000 (Tutsi only) |

| Perpetrators |

|

| Motive | Anti-Tutsi racism, Hutu Power |

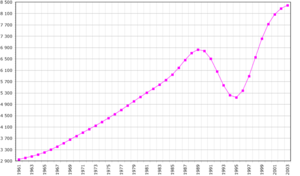

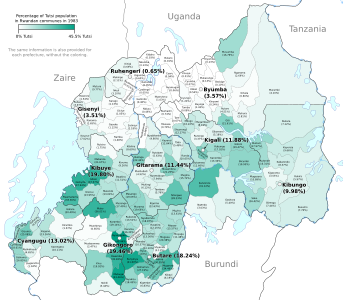

The Rwandan genocide occurred between 7 April and 15 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu militias. The most widely accepted scholarly estimates are around 500,000 to 662,000 Tutsi deaths.

Contents

Outline

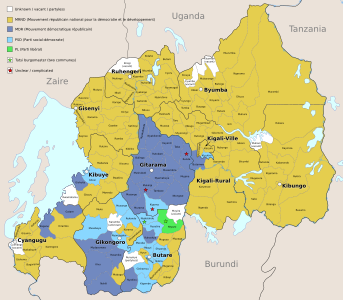

In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group composed mostly of Tutsi refugees, invaded northern Rwanda from their base in Uganda, initiating the Rwandan Civil War. Over the course of the next three years, neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage. In an effort to bring the war to a peaceful end, the Rwandan government led by Hutu president, Juvénal Habyarimana signed the Arusha Accords with the RPF on 4 August 1993. The catalyst became Habyarimana's assassination on 6 April 1994, creating a power vacuum and ending peace accords. Genocidal killings began the following day when majority Hutu soldiers, police, and militia murdered key Tutsi and moderate Hutu military and political leaders.

The scale and brutality of the genocide caused shock worldwide, but no country intervened to forcefully stop the killings. Most of the victims were killed in their own villages or towns, many by their neighbors and fellow villagers. Hutu gangs searched out victims hiding in churches and school buildings. The RPF quickly resumed the civil war once the genocide started and captured all government territory, ending the genocide and forcing the government and génocidaires into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

The genocide had lasting and profound effects. In 1996, the RPF-led Rwandan government launched an offensive into Zaire, home to exiled leaders of the former Rwandan government and many Hutu refugees, starting the First Congo War and killing an estimated 200,000 people. Today, Rwanda has two public holidays to mourn the genocide, and "genocide ideology" and "divisionism" are criminal offences. Although the Constitution of Rwanda states that more than 1 million people perished in the genocide, the real number killed is likely lower.

Aftermath

Hutu refugees particularly entered the eastern portion of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC). Hutu genocidaires began to regroup in refugee camps along the border with Rwanda. Declaring a need to avert further genocide, the RPF-led government made military incursions into Zaire, resulting in the First (1996–97) and Second (1998–2003) Congo Wars. Armed struggles between the Rwandan government and their opponents in the DRC have continued through battles of proxy militias in the Goma region, including the M23 rebellion (2012–2013). Large Rwandan Hutu and Tutsi populations continue to live as refugees throughout the region.

Refugee crisis, insurgency, and two Congo Wars

Following the RPF victory, approximately two million Hutu fled to refugee camps in neighbouring countries, particularly Zaire, fearing RPF reprisals for the Rwandan genocide. The camps were crowded and squalid, and thousands of refugees died in disease epidemics, including cholera and dysentery. The camps were set up by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), but were effectively controlled by the army and government of the former Hutu regime, including many leaders of the genocide, who began rearming in a bid to return to power in Rwanda.

By late 1996, Hutu militants from the camps were launching regular cross-border incursions, and the RPF-led Rwandan government launched a counteroffensive. Rwanda provided troops and military training to the Banyamulenge, a Tutsi group in the Zairian South Kivu province, helping them to defeat Zairian security forces. Rwandan forces, the Banyamulenge, and other Zairian Tutsi, then attacked the refugee camps, targeting the Hutu militia. These attacks caused hundreds of thousands of refugees to flee; many returned to Rwanda despite the presence of the RPF, while others ventured further west into Zaire. The refugees fleeing further into Zaire were relentlessly pursued by the RPA under the cover of the AFDL rebellion and 232,000 Hutu refugees were killed, according to one estimate. The defeated forces of the former regime continued a cross-border insurgency campaign, supported initially by the predominantly Hutu population of Rwanda's northwestern prefectures. By 1999, a programme of propaganda and Hutu integration into the national army succeeded in bringing the Hutu to the government side and the insurgency was defeated.

In addition to dismantling the refugee camps, Kagame began planning a war to remove long-time dictator Mobutu Sese Seko from power. Mobutu had supported the genocidaires based in the camps, and was also accused of allowing attacks on Tutsi people within Zaire. Together with Uganda, the Rwandan government supported an alliance of four rebel groups headed by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, which began waging the First Congo War in 1996. The rebels quickly took control of the North and South Kivu provinces and later advanced west, gaining territory from the poorly organised and demotivated Zairian army with little fighting, and controlling the whole country by 1997. Mobutu fled into exile, and Zaire was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). However, Rwanda fell out with the new Congolese government in 1998, and Kagame supported a fresh rebellion, leading to the Second Congo War, which would last up until 2003 and caused millions of deaths and massive damage. In 2010, a United Nations (UN) report accused the Rwandan army of committing wide-scale human rights violations and crimes against humanity in the Congo during those wars, charges denied by the Rwandan government.

Domestic situation

The infrastructure and economy of the country had suffered greatly during the genocide. Many buildings were uninhabitable, and the former regime had carried with them all currency and moveable assets when they fled the country. Human resources were also severely depleted, with over 40% of the population having been killed or fled. The army, led by Paul Kagame, maintained law and order while the government began the work of rebuilding the country's structures.

Non-governmental organisations began to move back into the country, but the international community did not provide significant assistance to the new government, and most international aid was routed to the refugee camps which had formed in Zaire following the exodus of Hutu from Rwanda. Kagame strove to portray the new government as inclusive and not Tutsi-dominated. He directed the removal of ethnicity from Rwandan citizens' national identity cards, and the government began a policy of downplaying the distinctions between Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa.

Justice system after genocide

The systematic destruction of the judicial system during the genocide and civil war was a major problem. After the genocide, over one million people (nearly one-fifth of the population remaining after the summer of 1994) were potentially culpable for a role in the genocide. The RPF pursued a policy of mass arrests for those responsible and for those persons who took part in the genocide, jailing over 100,000 people in the two years after the genocide. The pace of arrests overwhelmed the physical capacity of the Rwandan prison system, leading to what Amnesty International deemed "cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment". The country's 19 prisons were designed to hold about 18,000 inmates total, but at their peak in 1998 there were over 100,000 people in crowded detention facilities across the country.

It was not until 1996 that courts finally began trials for genocide cases with the enactment of Organic Law No. 08/96 of 30 on 30 August 1996. This law initiated the prosecution of genocide crimes committed during the genocide and of crimes against humanity from October 1990. The Organic Law established four categories for those who were involved in the genocide, specifying the limits of punishment for members of each category. The first category was reserved those who were "planners, organizers, instigators, supervisors and leaders" of the genocide and any who used positions of state authority to promote the genocide. This category also applied to murderers who distinguished themselves on the basis of their zeal or cruelty. Members of this first category were eligible for the death sentence.

While Rwanda had the death penalty prior to the 1996 Organic law, in practice no executions had taken place since 1982. Twenty-two individuals, including Froduald Karamira, were executed by firing squad in public executions in April 1998. After this, Rwanda conducted no further executions, albeit it continued to issue death sentences until 2003. On 25 July 2007 the Organic Law Relating to the Abolition of the Death Penalty came into law, abolishing capital punishment and converting all existing death sentences to life in prison under solitary confinement. In parallel, the 2007 UN resolution presented and campaigns continued for a global moratorium on capital punishment.

Gacaca courts

In response to the overwhelming number of potentially culpable individuals and the slow pace of the traditional judicial system, the government of Rwanda passed Organic Law No. 40/2000 in 2001. This law established Gacaca Courts at all administrative levels of Rwanda and in Kigali. It was mainly created to lessen the burden on normal courts and provide assistance in the justice system to run trials for those already in prison. The least severe cases, according to the terms of Organic Law No. 08/96 of 30, would be handled by these Gacaca Courts. With this law, the government began implementing a participatory justice system, known as Gacaca, in order to address the enormous backlog of cases. The Gacaca court system traditionally dealt with conflicts within communities, but it was adapted to deal with genocide crimes. Among the principal objectives of the courts were identification of the truth about what happened during the genocide, speeding up the process of trying genocide suspects, national unity and reconciliation, and demonstrating the capacity of the Rwandan people to resolve their own problems.

The Gacaca court system faced many controversies and challenges; they were accused of being puppets of the RPF-dominated government. The judges (known as Inyangamugayo, which means "those who detest dishonesty" in Kinyarwanda) who preside over the genocide trials were elected by the public. After election, the judges received training, but there was concern that the training was not adequate for serious legal questions or complex proceedings. Furthermore, many judges resigned after facing accusations of participating in the genocide; 27% of them were so accused. There was also a lack of defense counsel and protections for the accused, who were denied the right to appeal to ordinary courts. Most trials were open to the public, but there were issues with witness intimidation. The Gacaca courts did not try those responsible for massacres of Hutu civilians committed by members of the RPF, which controlled the Gacaca Court system.

On 18 June 2012, the Gacaca court system was officially closed after facing criticism. It is estimated that the Gacaca court system tried 1,958,634 cases during its lifetime and that 1,003,227 persons stood trial.

Censorship

Under the Rwandan constitution, "revisionism, negationism and trivialisation of genocide" are criminal offences. Hundreds of people have been tried and convicted for "genocide ideology", "revisionism", and other laws ostensibly related to the genocide. According to Amnesty International, of the 489 individuals convicted of "genocide revisionism and other related crimes" in 2009, five were sentenced to life imprisonment, five were sentenced to more than 20 years in jail, 99 were sentenced to 10–20 years in jail, 211 received a custodial sentence of 5–10 years, and the remaining 169 received jail terms of less than five years. Amnesty International has criticized the Rwandan government for using these laws to "criminalize legitimate dissent and criticism of the government". In 2010, Peter Erlinder, an American law professor and attorney, was arrested in Kigali and charged with genocide denial while serving as defense counsel for presidential candidate Victoire Ingabire.

Survivors

The number of Tutsi survivors of the genocide has been debated. Different figures between 150,000 and 309,368 have been offered. There are a number of organizations representing and supporting these survivors of the genocide. These include the Survivors Fund, IBUKA and AVEGA. The 2007 report on the living conditions of survivors conducted by the Ministry in charge of Social Affairs in Rwanda reported the following situation of survivors in the country:

| Category | Number of survivors |

|---|---|

| Very vulnerable survivors | 120,080 |

| Shelterless | 39,685 |

| Orphans living in households headed by children | 28,904 |

| Widows | 49,656 |

| Disabled during the genocide | 27,498 |

| Children and youth with no access to school | 15,438 |

| Graduates from high school with no access to higher education | 8,000 |

Media and popular culture

Canadian Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire became the best-known eyewitness to the genocide after co-writing the book Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (2003) describing his experiences with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Dallaire's book was made into the movie Shake Hands with the Devil (2007). Former journalist and United States Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power is interviewed about the Rwandan genocide in Watchers of the Sky (2014), a documentary by Edet Belzberg about genocide throughout history and its eventual inclusion in international law.

The critically acclaimed and multiple Academy Award-nominated film Hotel Rwanda (2004) is based on the experiences of Paul Rusesabagina, a Kigali hotelier at the Hôtel des Mille Collines who sheltered over a thousand refugees during the genocide. The independent documentary film Earth Made of Glass (2010), which addresses the personal and political costs of the genocide, focusing on Rwandan President Paul Kagame and genocide survivor Jean-Pierre Sagahutu, premiered at the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival.

HBO Films released the made-for-television historical drama film titled Sometimes in April in 2005.

In 2005, Alison Des Forges wrote that eleven years after the genocide, films for popular audiences on the subject greatly increased the "widespread realization of the horror that had taken the lives of more than half a million Tutsi". In 2007, Charlie Beckett, Director of POLIS, said: "How many people saw the movie Hotel Rwanda? [It is] ironically the way that most people now relate to Rwanda."

Pierre Rutare, the Tutsi father of Belgian-Rwandan singer Stromae, was killed in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.

Commemoration

In March 2019, President Félix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of the Congo visited Rwanda to sign the Kigali Genocide Memorial Book, saying, "The collateral effects of these horrors have not spared my country, which has also lost millions of lives." On 7 April the Rwandan Government initiated 100 days of mourning in observation of the 25th anniversary of the genocide by lighting a flame at the Kigali Genocide Memorial. Dignitaries from Chad, the Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Niger, Belgium, Canada, Ethiopia, the African Union and the European Union attended.

Maps of Rwanda

Images for kids

-

Paul Kagame, commander of the Rwandan Patriotic Front for most of the Civil War

See also

In Spanish: Genocidio de Ruanda para niños

In Spanish: Genocidio de Ruanda para niños

- Outline of Genocide studies