Amnesty International facts for kids

|

|

| Founded | July 1961 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Founders |

|

| Type |

|

| Headquarters | London, WC1 United Kingdom |

| Location |

|

| Services | Protecting human rights |

| Fields | Media attention, direct-appeal campaigns, research, lobbying |

|

Members

|

More than ten million members and supporters |

| Agnès Callamard | |

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organisation focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organisation says it has more than ten million members and supporters around the world. The stated mission of the organisation is to campaign for "a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments." The organisation has played a notable role on human rights issues due to its frequent citation in media and by world leaders.

AI was founded in London in 1961 by the lawyer Peter Benenson. In what he called "The Forgotten Prisoners" and "An Appeal for Amnesty", which appeared on the front page of the British newspaper The Observer, Benenson wrote about two students who toasted to freedom in Portugal and four other people who had been jailed in other nations because of their beliefs. AI's original focus was prisoners of conscience, with its remit widening in the 1970s, under the leadership of Seán MacBride and Martin Ennals to include miscarriages of justice and torture. In 1977, it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In the 1980s, its secretary general was Thomas Hammarberg, succeeded in the 1990s by Pierre Sané. In the 2000s, it was led by Irene Khan.

Amnesty draws attention to human rights abuses and campaigns for compliance with international laws and standards. It works to mobilize public opinion to generate pressure on governments where abuse takes place.

Contents

History

1960s

Amnesty International was founded in London in July 1961 by English barrister Peter Benenson, who had previously been a founding member of the UK law reform organisation JUSTICE. Benenson was influenced by his friend Louis Blom-Cooper, who led a political prisoners' campaign. In 1960, Portugal was ruled by the Estado Novo government of António de Oliveira Salazar. The government was authoritarian in nature and strongly anti-communist, suppressing enemies of the state as anti-Portuguese. In his significant newspaper article "The Forgotten Prisoners", Benenson later described his reaction as follows:

Open your newspaper any day of the week and you will find a story from somewhere of someone being imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government... The newspaper reader feels a sickening sense of impotence. Yet if these feelings of disgust could be united into common action, something effective could be done.

Benenson worked with his friend Eric Baker – a member of the Religious Society of Friends who had been involved in funding the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament as well as becoming head of Quaker Peace and Social Witness. In his memoirs, Benenson described him as "a partner in the launching of the project". In consultation with other writers, academics and lawyers and, in particular, Alec Digges, they wrote via Louis Blom-Cooper to David Astor, editor of The Observer newspaper, who, on 28 May 1961, published Benenson's article "The Forgotten Prisoners". The article brought the reader's attention to those "imprisoned, tortured or executed because his opinions or religion are unacceptable to his government" or, put another way, to violations, by governments, of articles 18 and 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The article described these violations occurring, on a global scale, in the context of restrictions to press freedom, to political oppositions, to timely public trial before impartial courts, and to asylum. It marked the launch of "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961", the aim of which was to mobilize public opinion, quickly and widely, in defence of these individuals, whom Benenson named "Prisoners of Conscience".

The "Appeal for Amnesty" was reprinted by a large number of international newspapers. In the same year, Benenson had a book published, Persecution 1961, which detailed the cases of nine prisoners of conscience investigated and compiled by Benenson and Baker (Maurice Audin, Ashton Jones, Agostinho Neto, Patrick Duncan, Olga Ivinskaya, Luis Taruc, Constantin Noica, Antonio Amat and Hu Feng).

In July 1961, the leadership had decided that the appeal would form the basis of a permanent organisation, Amnesty, with the first meeting taking place in London. Benenson ensured that all three major political parties were represented, enlisting members of parliament from the Labour Party, the Conservative Party, and the Liberal Party. On 30 September 1962, it was officially named "Amnesty International". Between the "Appeal for Amnesty, 1961" and September 1962 the organisation had been known simply as "Amnesty".

By the mid-1960s, Amnesty International's global presence was growing and an International Secretariat and International Executive Committee were established to manage Amnesty International's national organisations, called "Sections", which had appeared in several countries. They were secretly supported by the British government at the time. The international movement was starting to agree on its core principles and techniques. For example, the issue of whether or not to adopt prisoners who had advocated violence, like Nelson Mandela, brought unanimous agreement that it could not give the name of "Prisoner of Conscience" to such prisoners. Aside from the work of the library and groups, Amnesty International's activities were expanding to helping prisoners' families, sending observers to trials, making representations to governments, and finding asylum or overseas employment for prisoners. Its activity and influence were also increasing within intergovernmental organisations; it would be awarded consultative status by the United Nations, the Council of Europe and UNESCO before the decade ended.

In 1966, Benenson suspected that the British government in collusion with some Amnesty employees had suppressed a report on British atrocities in Aden. He began to suspect that many of his colleagues were part of a British intelligence conspiracy to subvert Amnesty, but he could not convince anybody else at AI. Later in the same year there were further allegations, when the US government reported that Seán MacBride, the former Irish foreign minister and Amnesty's first chairman, had been involved with a Central Intelligence Agency funding operation. MacBride denied knowledge of the funding, but Benenson became convinced that MacBride was a member of a CIA network. Benenson resigned as Amnesty's president on the grounds that it was bugged and infiltrated by the secret services, and said that he could no longer live in a country where such activities were tolerated. (See Relationship with the British Government)

1970s–1980s

Amnesty International's membership increased from 15,000 in 1969 to 200,000 by 1979. At the intergovernmental level Amnesty International pressed for the application of the UN's Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners and of existing humanitarian conventions; to secure ratifications of the two UN Covenants on Human Rights in 1976, and was instrumental in obtaining additional instruments and provisions forbidding the practice of maltreatment. Consultative status was granted at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1972.

Amnesty International established its Japan chapter in 1970, in part a response to the Republic of China (Taiwan)'s arrest and prosecution of Chen Yu-hsi, whom the Taiwan Garrison Command had alleged committed sedition by reading communist literature while studying in the United States.

In 1976, Amnesty's British Section started a series of fund-raising events that came to be known as The Secret Policeman's Balls series. They were staged in London initially as comedy galas featuring what The Daily Telegraph called "the crème de la crème of the British comedy world" including members of comedy troupe Monty Python, and later expanded to also include performances by leading rock musicians. The series was created and developed by Monty Python alumnus John Cleese and entertainment industry executive Martin Lewis working closely with Amnesty staff members Peter Luff (assistant director of Amnesty 1974–1978) and subsequently with Peter Walker (Amnesty Fund-Raising Officer 1978–1982). Cleese, Lewis and Luff worked together on the first two shows (1976 and 1977). Cleese, Lewis and Walker worked together on the 1979 and 1981 shows, the first to carry what The Daily Telegraph described as the "rather brilliantly re-christened" Secret Policeman's Ball title.

The organisation was awarded the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize for its "defence of human dignity against torture" and the United Nations Prize in the Field of Human Rights in 1978.

During the mid-to-late-1980s, Amnesty organised two major musical events took place to increase awareness of Amnesty and of human rights. The 1986 Conspiracy of Hope tour, which played five concerts in the US, and culminated in a daylong show, featuring some thirty-odd acts at Giants Stadium, and the 1988 Human Rights Now! world tour. Human Rights Now!, which was timed to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), played a series of concerts on five continents over six weeks. Both tours featured some of the most famous musicians and bands of the day.

1990s

Throughout the 1990s, Amnesty continued to grow, to a membership of over seven million in over 150 countries and territories, led by Senegalese Secretary General Pierre Sané. At the intergovernmental level, Amnesty International argued in favour of creating a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (established 1993) and an International Criminal Court (established 2002).

Amnesty continued to work on a wide range of issues and world events. For example, South African groups joined in 1992 and hosted a visit by Pierre Sané to meet with the apartheid government to press for an investigation into allegations of police abuse, an end to arms sales to the African Great Lakes region and the abolition of the death penalty. In particular, Amnesty International brought attention to violations committed on specific groups, including refugees, racial/ethnic/religious minorities, women and those executed or on Death Row.

In 1995, when AI wanted to promote how Shell Oil Company was involved with the execution of an environmental and human-rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa in Nigeria, it was stopped. Newspapers and advertising companies refused to run AI's ads because Shell Oil was a customer of theirs as well. Shell's main argument was that it was drilling oil in a country that already violated human rights and had no way to enforce human-rights policies. To combat the buzz that AI was trying to create, it immediately publicized how Shell was helping to improve overall life in Nigeria. Salil Shetty, the director of Amnesty, said, "Social media re-energises the idea of the global citizen". James M. Russell notes how the drive for profit from private media sources conflicts with the stories that AI wants to be heard.

Amnesty International became involved in the legal battle over Augusto Pinochet, former Chilean dictator, who sought to avoid extradition to Spain to face charges after his arrest in London in 1998 by the Metropolitan Police. Lord Hoffman had an indirect connection with Amnesty International, and this led to an important test for the appearance of bias in legal proceedings in UK law. There was a suit against the decision to release Senator Pinochet, taken by the then British Home Secretary Jack Straw, before that decision had actually been taken, in an attempt to prevent the release of Senator Pinochet. The English High Court refused the application, and Senator Pinochet was released and returned to Chile.

2000s

After 2000, Amnesty International's primary focus turned to the challenges arising from globalization and the reaction to the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States. The issue of globalization provoked a major shift in Amnesty International policy, as the scope of its work was widened to include economic, social and cultural rights, an area that it had declined to work on in the past. Amnesty International felt this shift was important, not just to give credence to its principle of the indivisibility of rights, but because of what it saw as the growing power of companies and the undermining of many nation-states as a result of globalization.

In the aftermath of 11 September attacks, the new Amnesty International Secretary General, Irene Khan, reported that a senior government official had said to Amnesty International delegates: "Your role collapsed with the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York." In the years following the attacks, some believe that the gains made by human rights organisations over previous decades had possibly been eroded. Amnesty International argued that human rights were the basis for the security of all, not a barrier to it. Criticism came directly from the Bush administration and The Washington Post, when Khan, in 2005, likened the US government's detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to a Soviet Gulag.

During the first half of the new decade, Amnesty International turned its attention to violence against women, controls on the world arms trade, concerns surrounding the effectiveness of the UN, and ending torture. With its membership close to two million by 2005, Amnesty continued to work for prisoners of conscience.

Amnesty International reported, concerning the Iraq War, on 17 March 2008, that despite claims the security situation in Iraq has improved in recent months, the human rights situation is disastrous, after the start of the war five years earlier in 2003.

In 2009, Amnesty International accused Israel and the Palestinian Hamas movement of committing war crimes during Israel's January offensive in Gaza, called Operation Cast Lead, that resulted in the deaths of more than 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. The 117-page Amnesty report charged Israeli forces with killing hundreds of civilians and wanton destruction of thousands of homes. Amnesty found evidence of Israeli soldiers using Palestinian civilians as human shields. A subsequent United Nations Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict was carried out; Amnesty stated that its findings were consistent with those of Amnesty's own field investigation, and called on the UN to act promptly to implement the mission's recommendations.

2010s

Early 2010s

In February 2010, Amnesty suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticized Amnesty for its links with Moazzam Begg, director of Cageprisoners. She said it was "a gross error of judgment" to work with "Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban". Amnesty responded that Sahgal was not suspended "for raising these issues internally... [Begg] speaks about his own views ..., not Amnesty International's". Among those who spoke up for Sahgal were Salman Rushdie, Member of Parliament Denis MacShane, Joan Smith, Christopher Hitchens, Martin Bright, Melanie Phillips, and Nick Cohen.

In July 2011, Amnesty International celebrated its 50 years with an animated short film directed by Carlos Lascano, produced by Eallin Motion Art and Dreamlife Studio, with music by Academy Award-winner Hans Zimmer and nominee Lorne Balfe.

In August 2012, Amnesty International's chief executive in India sought an impartial investigation, led by the United Nations, to render justice to those affected by war crimes in Sri Lanka.

Mid-2010s

On 18 August 2014, in the wake of demonstrations sparked by people protesting about the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old who assaulted a police officer and then resisted arrest, and subsequent acquittal of Darren Wilson, the officer who shot him, Amnesty International sent a 13-person contingent of human rights activists to seek meetings with officials as well as to train local activists in non-violent protest methods. This was the first time that the organisation has deployed such a team to the United States.

In the 2015 annual Amnesty International UK conference, delegates narrowly voted (468 votes to 461) against a motion proposing a campaign against antisemitism in the UK. The debate on the motion formed a consensus that Amnesty should fight "discrimination against all ethnic and religious groups", but the division among delegates was over the issue of whether it would be appropriate for an anti-racism campaign with a "single focus". The Jewish Chronicle noted that Amnesty International had previously published a report on discrimination against Muslims in Europe.

In August 2015, The Times reported that Yasmin Hussein, then Amnesty's director of faith and human rights and previously its head of international advocacy and a prominent representative at the United Nations, had "undeclared private links to men alleged to be key players in a secretive network of global Islamists", including the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas. The Times also detailed instances where Hussein was alleged to have had inappropriately close relationships with the al-Qazzaz family, members of which were high-ranking government ministers in the administration of Mohammed Morsi and Muslim Brotherhood leaders at the time. Ms Hussein denied supporting the Muslim Brotherhood and told Amnesty that "any connections are purely circumstantial".

In June 2016, Amnesty International called on the United Nations General Assembly to "immediately suspend" Saudi Arabia from the UN Human Rights Council. Richard Bennett, head of Amnesty's UN Office, said: "The credibility of the U.N. Human Rights Council is at stake. Since joining the council, Saudi Arabia's dire human rights record at home has continued to deteriorate and the coalition it leads has unlawfully killed and injured thousands of civilians in the conflict in Yemen."

In December 2016, Amnesty International revealed that Voiceless Victims, a fake non-profit organisation which claims to raise awareness for migrant workers who are victims of human rights abuses in Qatar, had been trying to spy on their staff.

Late 2010s

In October 2018, an Amnesty International researcher was abducted and beaten while observing demonstrations in Magas, the capital of Ingushetia, Russia.

On 25 October, federal officers raided the Bengaluru office for 10 hours on a suspicion that the organisation had violated foreign direct investment guidelines on the orders of the Enforcement Directorate. Employees and supporters of Amnesty International say this is an act to intimidate organisations and people who question the authority and capabilities of government leaders. Aakar Patel, the executive director of the Indian branch claimed, "The Enforcement Directorate's raid on our office today shows how the authorities are now treating human rights organisations like criminal enterprises, using heavy-handed methods. On Sep 29, the Ministry of Home Affairs said Amnesty International using "glossy statements" about humanitarian work etc. as a "ploy to divert attention" from their activities which were in clear contravention of laid down Indian laws. Amnesty International received permission only once in Dec 2000, since then it had been denied Foreign Contribution permission under the Foreign Contribution Act by successive Governments. However, in order to circumvent the FCRA regulations, Amnesty UK remitted large amounts of money to four entities registered in India by classifying it as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

The current Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, has been criticized by foreign medias for harming civil society in India, specifically by targeting advocacy groups. India has cancelled the registration of about 15,000 nongovernmental organisations under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA); the U.N. has issued statements against the policies that allow these cancellations to occur. Though nothing was found to confirm these accusations, the government plans on continuing the investigation and has frozen the bank accounts of all the offices in India. A spokesperson for the Enforcement Directorate has said the investigation could take three months to complete.

On 30 October 2018, Amnesty called for the arrest and prosecution of Nigerian security forces claiming that they used excessive force against Shi'a protesters during a peaceful religious procession around Abuja, Nigeria. At least 45 were killed and 122 were injured during the event.

In November 2018, Amnesty reported the arrest of 19 or more rights activists and lawyers in Egypt. The arrests were made by the Egyptian authorities as part of the regime's ongoing crackdown on dissent. One of the arrested was Hoda Abdel-Monaim, a 60-year-old human rights lawyer and former member of the National Council for Human Rights. Amnesty reported that following the arrests Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) decided to suspend its activities due to the hostile environment towards civil society in the country.

On 5 December 2018, Amnesty International strongly condemned the execution of Ihar Hershankou and Siamion Berazhnoy in Belarus. They were shot despite UN Human Rights Committee request for a delay.

In February 2019, Amnesty International's management team offered to resign after an independent report found what it called a "toxic culture" of workplace bullying, and found evidence of bullying, harassment, sexism and racism.

In April 2019, Amnesty International's deputy director for research in Europe, Massimo Moratti, warned that if extradited to the United States, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange would face the "risk of serious human rights violations, namely detention conditions, which could violate the prohibition of torture".

On 14 May 2019, Amnesty International filed a petition with the District Court of Tel Aviv, Israel, seeking a revocation of the export licence of surveillance technology firm NSO Group. The filing states that "staff of Amnesty International have an ongoing and well-founded fear they may continue to be targeted and ultimately surveilled" by NSO technology. Other lawsuits have also been filed against NSO in Israeli courts over alleged human-rights abuses, including a December 2018 filing by Saudi dissident Omar Abdulaziz, who claimed NSO's software targeted his phone during a period in which he was in regular contact with murdered journalist Jamal Kashoggi.

In September 2019, European Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen created the new position of "Vice President for Protecting our European Way of Life", who will be responsible for upholding the rule-of-law, internal security and migration. Amnesty International accused the European Union of "using the framing of the far right" by linking migration with security.

On 24 November 2019, Anil Raj, a former Amnesty International board member, was killed by a car bomb while working with the United Nations Development Project. U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo announced Raj's death at a briefing 26 Nov, during which he discussed other acts of terrorism.

2020s

In August 2020, Amnesty International expressed concerns about what it called the "widespread torture of peaceful protesters" and treatment of detainees in Belarus. The organisation also said that more than 1,100 people were killed by bandits in rural communities in northern Nigeria during the first six months of 2020. Amnesty International investigated what it called "excessive" and "unlawful" killings of teenagers by Angolan police who were enforcing restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic.

In May 2020, the organisation raised concerns about security flaws in a COVID-19 contact tracing app mandated in Qatar.

In September 2020, Amnesty shut down its India operations after the government froze its bank accounts due to alleged financial irregularities.

On 2 November 2020, Amnesty International reported that 54 people – mostly Amhara women and children and elderly people – were killed by the OLF in the village of Gawa Qanqa, Ethiopia.

In April 2021, Amnesty International distanced itself from a tweet by Agnès Callamard, its newly appointed Secretary General, asserting that Israel had killed Yasser Arafat; Callamard herself has not deleted the tweet.

In February 2022, Amnesty accused Israel of committing the crime of apartheid against the Palestinians, joining other human rights organisations that had previously accused Israel of the crime against humanity. In 2021, Human Rights Watch and B'tselem both accused Israel of apartheid for its treatment of the Palestinians in the occupied territories. An Amnesty report stated that Israel maintains "an institutionalized regime of oppression and domination of the Palestinian population for the benefit of Jewish Israelis". The Israeli Foreign Ministry stated that Amnesty was peddling "lies, inconsistencies, and unfounded assertions that originate from well-known anti-Israeli hate organisations". The Palestinian Foreign Ministry called the report a "detailed affirmation of the cruel reality of entrenched racism, exclusion, oppression, colonialism, apartheid, and attempted erasure that the Palestinian people have endured".

In March 2022, Paul O'Brien, the Amnesty International USA Director, speaking to a Women's National Democratic Club audience in the US, stated: "We are opposed to the idea—and this, I think, is an existential part of the debate—that Israel should be preserved as a state for the Jewish people", while adding "Amnesty takes no political views on any question, including the right of the State of Israel to survive."

On 7 April 2022, six weeks after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian Ministry of Justice announced that the offices of Amnesty International and 14 other well-known international organisations had been closed for "violations of Russian law".

Structure

Amnesty International is largely made up of voluntary members but retains a small number of paid professionals. In countries in which Amnesty International has a strong presence, members are organized as "sections". In 2019 there were 63 sections worldwide. The highest governing body is the Global Assembly which meets annually, attended by the chair and executive director of each section.

The International Secretariat (IS) is responsible for the conduct and daily affairs of Amnesty International under direction from the International Board. It is run by approximately 500 professional staff members and is headed by a Secretary General. Its offices have been located in London since its establishment in the mid-1960s.

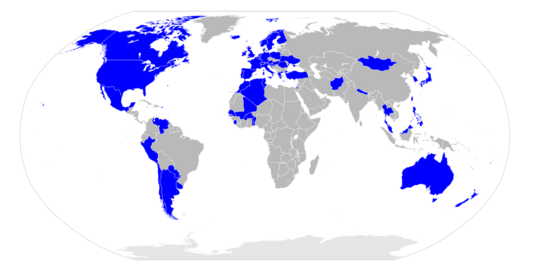

- Amnesty International Sections, 2005

Algeria; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium (Dutch-speaking); Belgium (French-speaking); Benin; Bermuda; Canada (English-speaking); Canada (French-speaking); Chile; Côte d'Ivoire; Denmark; Faroe Islands; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Guyana; Hong Kong; Iceland; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Korea (Republic of); Luxembourg; Mauritius; Mexico; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; New Zealand; Norway; Peru; Philippines; Poland; Portugal; Puerto Rico; Senegal; Sierra Leone; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Taiwan; Togo; Tunisia; United Kingdom; United States of America; Uruguay; Venezuela - Amnesty International Structures, 2005

Belarus; Bolivia; Burkina Faso; Croatia; Curaçao; Czech Republic; Gambia; Hungary; Malaysia; Mali; Moldova; Mongolia; Pakistan; Paraguay; Slovakia; South Africa; Thailand; Turkey; Ukraine; Zambia; Zimbabwe - International Board (formerly known as "IEC") Chairpersons

Seán MacBride, 1965–74; Dirk Börner, 1974–17; Thomas Hammarberg, 1977–79; José Zalaquett, 1979–82; Suriya Wickremasinghe, 1982–85; Wolfgang Heinz, 1985–96; Franca Sciuto, 1986–89; Peter Duffy, 1989–91; Anette Fischer, 1991–92; Ross Daniels, 1993–19; Susan Waltz, 1996–98; Mahmoud Ben Romdhane, 1999–2000; Colm O Cuanachain, 2001–02; Paul Hoffman, 2003–04; Jaap Jacobson, 2005; Hanna Roberts, 2005–06; Lilian Gonçalves-Ho Kang You, 2006–07; Peter Pack, 2007–11; Pietro Antonioli, 2011–13; and Nicole Bieske, 2013–2018, Sarah Beamish (2019 to current). - Secretaries General

| Secretary General | Office | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Peter Benenson | 1961–1966 | Britain |

| Eric Baker | 1966–1968 | Britain |

| Martin Ennals | 1968–1980 | Britain |

| Thomas Hammarberg | 1980–1986 | Sweden |

| Ian Martin | 1986–1992 | Britain |

| Pierre Sané | 1992–2001 | Senegal |

| Irene Khan | 2001–2010 | Bangladesh |

| Salil Shetty | 2010–2018 | India |

| Kumi Naidoo | 2018–2020 | South Africa |

| Julie Verhaar | 2020–2021 (Acting) | |

| Agnès Callamard | 2021–present | France |

Notable national sections

- Amnesty International Ghana

- Amnesty International Australia

- Amnesty International India

- Amnesty International Ireland

- Amnesty International New Zealand

- Amnesty International Philippines

- Amnesty International South Africa

- Amnesty International Thailand

- Amnesty International USA

Charitable status

In the UK Amnesty International has two components which are registered charities under English law: Amnesty International Charity and Amnesty International UK Section Charitable Trust.

Principles

The core principle of Amnesty International is a focus on prisoners of conscience, those persons imprisoned or prevented from expressing an opinion by means of violence. Along with this commitment to opposing repression of freedom of expression, Amnesty International's founding principles included non-intervention on political questions, a robust commitment to gathering facts about the various cases and promoting human rights.

One key issue in the principles is in regards to those individuals who may advocate or tacitly support resorting to violence in struggles against repression. AI does not judge whether recourse to violence is justified or not. However, AI does not oppose the political use of violence in itself since The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in its preamble, foresees situations in which people could "be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression". If a prisoner is serving a sentence imposed, after a fair trial, for activities involving violence, AI will not ask the government to release the prisoner.

AI neither supports nor condemns the resort to violence by political opposition groups in itself, just as AI neither supports nor condemns a government policy of using military force in fighting against armed opposition movements. However, AI supports minimum humane standards that should be respected by governments and armed opposition groups alike. When an opposition group tortures or kills its captives, takes hostages, or commits deliberate and arbitrary killings, AI condemns these abuses.

Amnesty International considers capital punishment to be the ultimate, irreversible denial of human rights and opposes capital punishment in all cases, regardless of the crime committed, the circumstances surrounding the individual or the method of execution.

Objectives

Amnesty International primarily targets governments, but also reports on non-governmental bodies and private individuals ("non-state actors").

There are six key areas which Amnesty deals with:

- Women's, children's, minorities' and indigenous rights

- Ending torture

- Abolition of the death penalty

- Rights of refugees

- Rights of prisoners of conscience

- Protection of human dignity.

Some specific aims are to: abolish the death penalty, end extra judicial executions and "disappearances", ensure prison conditions meet international human rights standards, ensure prompt and fair trial for all political prisoners, ensure free education to all children worldwide, fight impunity from systems of justice, end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, free all prisoners of conscience, promote economic, social and cultural rights for marginalized communities, protect human rights defenders, promote religious tolerance, protect LGBT rights, stop torture and ill-treatment, stop unlawful killings in armed conflict, uphold the rights of refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers, and protect human dignity.

Amnesty International launched a free human rights learning mobile application called Amnesty Academy in October 2020. It offered learners across the globe access to courses both, online and offline. All courses are downloadable within the application, which is available for both iOS and Android devices.

Country focus

Amnesty reports disproportionately on relatively more democratic and open countries, arguing that its intention is not to produce a range of reports which statistically represents the world's human rights abuses, but rather to apply the pressure of public opinion to encourage improvements.

The demonstration effect of the behaviour of both key Western governments and major non-Western states is an important factor; as one former Amnesty Secretary-General pointed out, "for many countries and a large number of people, the United States is a model", and according to one Amnesty manager, "large countries influence small countries." In addition, with the end of the Cold War, Amnesty felt that a greater emphasis on human rights in the North was needed to improve its credibility with its Southern critics by demonstrating its willingness to report on human rights issues in a truly global manner.

According to one academic study, as a result of these considerations, the frequency of Amnesty's reports is influenced by a number of factors, besides the frequency and severity of human rights abuses. For example, Amnesty reports significantly more (than predicted by human rights abuses) on more economically powerful states; and on countries that receive US military aid, on the basis that this Western complicity in abuses increases the likelihood of public pressure being able to make a difference. In addition, around 1993–94, Amnesty consciously developed its media relations, producing fewer background reports and more press releases, to increase the impact of its reports. Press releases are partly driven by news coverage, to use existing news coverage as leverage to discuss Amnesty's human rights concerns. This increases Amnesty's focus on the countries the media is more interested in.

In 2012, Kristyan Benedict, Amnesty UK's campaign manager whose main focus is Syria, listed several countries as "regimes who abuse peoples' basic universal rights": Burma, Iran, Israel, North Korea and Sudan. Benedict was criticized for including Israel in this short list on the basis that his opinion was garnered solely from "his own visits", with no other objective sources.

Amnesty's country focus is similar to that of some other comparable NGOs, notably Human Rights Watch: between 1991 and 2000, Amnesty and HRW shared eight of ten countries in their "top ten" (by Amnesty press releases; 7 for Amnesty reports). In addition, six of the 10 countries most reported on by Human Rights Watch in the 1990s also made The Economist's and Newsweek's "most covered" lists during that time.

Funding

Amnesty International is financed largely by fees and donations from its worldwide membership. It says that it does not accept donations from governments or governmental organisations.

However, Amnesty International has received grants over the past ten years from the UK Department for International Development, the European Commission, the United States State Department and other governments.

Amnesty International USA has received funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, but these funds are only used "in support of its human rights education work." It has also received many grants from the Ford Foundation over the years.

Awards and honours

In 1977, Amnesty International was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for "having contributed to securing the ground for freedom, for justice, and thereby also for peace in the world".

In 1984, Amnesty International received the Four Freedoms Award in the category of Freedom of Speech.

Cultural impact

Human rights concerts

A Conspiracy of Hope was a short tour of six benefit concerts on behalf of Amnesty International that took place in the United States during June 1986. The purpose of the tour was not to raise funds but rather to increase awareness of human rights and of Amnesty's work on its 25th anniversary. The shows were headlined by U2, Sting and Bryan Adams and also featured Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Joan Baez, and The Neville Brothers. The last three shows featured a reunion of The Police. At a press conference in each city, at related media events, and through their music at the concerts themselves, the artists engaged with the public on themes of human rights and human dignity. The six concerts were the first of what subsequently became known collectively as the Human Rights Concerts – a series of music events and tours staged by Amnesty International USA between 1986 and 1998.

Human Rights Now! was a worldwide tour of twenty benefit concerts on behalf of Amnesty International that took place over six weeks in 1988. Held not to raise funds but to increase awareness of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on its 40th anniversary and the work of Amnesty International, the shows featured Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Sting, Peter Gabriel, Tracy Chapman, and Youssou N'Dour, plus guest artists from each of the countries where concerts were held.

The Amnesty Candle

The organisation's logo combines two recognisable images inspired by the proverb, "Better to light a candle than curse the darkness." The candle represents the organisation's efforts to bring light to the fact that political prisoners are held all over the world and its commitment to bring the prisoners hope for fair treatment and release. The barbed wire represents the hopelessness of people unjustly put in jail.

The logo was designed by Diana Redhouse in 1963 as Amnesty's first Christmas card.

See also

In Spanish: Amnistía Internacional para niños

In Spanish: Amnistía Internacional para niños

- Ambassador of Conscience Award

- Amnesty International UK Media Awards

- List of Amnesty International UK Media Awards winners

- List of peace activists

- Scholars at Risk

- World Coalition Against the Death Penalty