Rincon Hill, San Francisco facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rincon Hill

|

|

|---|---|

Rincon Hill neighborhood viewed from across the San Francisco Bay.

|

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.25 km2 (0.096 sq mi) |

| • Land | 0.25 km2 (0.096 sq mi) |

| Population

(2008)

|

|

| • Total | 1,532 |

| • Density | 6,155/km2 (15,942/sq mi) |

| ZIP code |

94105

|

| Area codes | 415/628 |

| Reference #: | 84 |

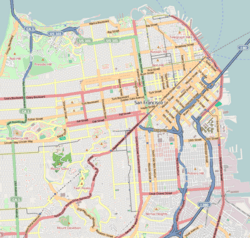

Rincon Hill (Spanish Rincón, meaning "corner") is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California. It is one of San Francisco's many hills, and one of its original "Seven Hills". The relatively compact neighborhood is bounded by Folsom Street to the north, the Embarcadero to the east, Bryant Street on the south, and Essex Street to the west. Named after Rincon Point that formerly extended into the bay there, Rincon Hill is located just south of the Transbay development area, part of the greater South of Market area. The hill is about 100 feet (30 m) tall.

Following the California Gold Rush, Rincon Hill was built up as a fashionable and prestigious residential neighborhood. After it was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire, the neighborhood was slow to rebuild and largely became an industrial area with small factories and warehouses. In 1985, and revised in 2005, the area was rezoned into a high-density residential neighborhood designed to house up to 10,000 new residents in close proximity to the city's Financial District.

Contents

History

The area comprising Rincon Hill was originally a sandy peninsula forming the southern shoreline of Yerba Buena Cove. The peninsula terminated at Rincon Point, near Harrison and Spear streets, from which Rincon Hill derives its name. Rincón is Spanish for "corner", and the point formed the southern corner of the cove. Prior to the Gold Rush of 1849, the Rincon Hill area was largely unsettled, as most early development was on the north side of the Cove, near Portsmouth Square.

Gold Rush to the 1906 quake

With the influx of gold seekers, the cove was filled in and the street grid expanded. Rincon Hill's views and sunny climate made it attractive to families of merchants, sea captains, and other professional classes who sought refuge from the notorious Barbary Coast. During the 1850s and 1860s, the city's most prestigious residential neighborhoods were located south of Market Street on Rincon Hill and in the nearby neighborhood known as Happy Valley (centered around First and Market Streets).

The Second Street Cut of 1869, which sliced through Rincon Hill to reach industrial areas to the south, marked the beginning of the end of Rincon Hill as a fashionable residential area. A wealthy land owner and state assemblyman, John Middleton, proposed the leveling of Second Street through Rincon Hill to improve access to the city's southern waterfront. The 100-foot (30 m) canyon split Rincon Hill in two and destabilized homes on either side.

With the advent of cable cars in the 1870s, the residential trend shifted towards new mansions built on the taller hills north of Market Street, especially Nob Hill. In The Wrecker (1892), Robert Louis Stevenson described Rincon Hill as "a new slum, a place of precarious sandy cliffs, deep sandy cuttings, solitary ancient houses and butt ends of streets."

Decline and industrial transition

The 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed the remaining Rincon Hill mansions. In their place, a number of rudimentary earthquake shacks sprung up and remained for decades. While much of San Francisco was quickly rebuilt following the earthquake, Rincon Hill remained relatively undeveloped in the ensuing decades. Following the quake, the Marsden Manson report on reconstruction recommended that Rincon Hill be removed entirely to provide more flat ground close to the waterfront. Although the plan was never enacted, it resurfaced in 1913 and 1927, discouraging real estate developers from building on the hill.

The construction of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge in the 1930s cleared out the remaining shacks, transforming the landscape of the neighborhood yet again. While the bridge was under construction, Rincon Hill was recognized as a California Historical Landmark in 1933, with the plaque reading in part:

A fashionable neighborhood in the 1860s, Rincon Hill was the home of William Tecumseh Sherman, William C. Ralston, William Gwin, H. H. Bancroft, and others. By the 1880s the hill, already partially leveled, became a working-class district. Today it is nearly invisible beneath the Bay Bridge.

With new vehicular access to the East Bay, the area was slowly built up as an industrial and maritime district, benefiting from its proximity to the Port of San Francisco and the Southern Pacific rail yards in Mission Bay. In 1934, Rincon Hill was the site of the "Bloody Thursday" clashes between striking longshoreman and police, in which two maritime workers were killed, leading to a four-day general strike.

In the 1950s, the Embarcadero Freeway was constructed along Folsom Street, surrounding the neighborhood on three sides by freeway ramps, and cutting it off from the Financial District. As the city's industrial and maritime industries declined (as in most U.S. cities), the area became underutilized and rundown. From the 1960s to the mid-1980s, while the nearby Financial District was built up with dozens of new office skyscrapers, the Rincon Hill area was largely ignored.

High-density residential neighborhood

While its potential for housing development has long been recognized due to its proximity to downtown, blight prevented its effective redevelopment. In 1985, the city adopted an area plan for Rincon Hill in the city's General Plan, zoning this area adjacent to downtown for high-density residential development. However, due to the presence of the former elevated Embarcadero Freeway surrounding the neighborhood, development in the area was slow in coming, suffered from mediocre architecture, and lacked the pedestrian-oriented streets and open spaces emblematic of San Francisco's cherished neighborhoods. As the city later noted, "Rincon Hill has seen the construction of bulky, closely spaced residential towers, which block public views, crowd streets, and contribute to a flat, unappealing skyline. These developments have also contributed little to the pedestrian environment, with multiple levels of above-ground parking, and garage entries and featureless walls facing the street."

After the physical and psychological barrier of the Embarcadero Freeway (damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake) was removed in the early 1990s, the area within walking distance of downtown gained new attractiveness. In August 2005, the City adopted a new Rincon Hill Plan, based more on Vancouverism than the 1985 Plan, that emphasizes tall, slender, and widely spaced towers, interspaced with mid-rise podiums and walk-up townhouses. It aims to accentuate the natural topography of the city by locating the tallest skyscrapers at the top of Rincon Hill. In tandem with the Transbay development plan just to the north, it designates Folsom Street as the commercial heart of the neighborhood. The plan calls for improving the pedestrian experience by narrowing the streets to provide more open space and providing more midblock passages.

Whereas the 1985 plan capped buildings heights at 250 feet (76 m), the new Rincon Hill Plan raised a number of height limits near the peak of Rincon Hill to 400 and 550 feet (170 m). Although a number of new residential developments were approved to take advantage of the changes, only The Infinity and one tower of 709-unit One Rincon Hill were constructed before the 2008 financial crisis halted projects throughout the city. As the economy recovered, the second tower of One Rincon Hill began construction in 2012; the 320-unit 45 Lansing Street and 655-unit LUMINA broke ground in 2013; and the 447-unit 399 Fremont Street started in 2014.

In July 2015, property owners voted to approve of the formation of the Greater Rincon Hill Community Benefit District, a non-profit, public-private partnership focused on advancing the neighborhood's quality of life, enhancing its public realm, and reinforcing the viability of its economic base. In 2017, to more accurately reflect the district boundaries and to unite the Rincon Hill, Folsom Street, and Transbay areas, the non-profit's name was changed to the East Cut Community Benefit District.