1906 San Francisco earthquake facts for kids

|

|

| UTC time | ?? |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 7.8 Mw |

| Depth | 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) |

| Epicenter | 37°45′N 122°33′W / 37.75°N 122.55°W |

| Areas affected | United States (San Francisco Bay Area) |

| Max. intensity | X - Intense |

| Casualties | 3,000+ (Estimated 3425) |

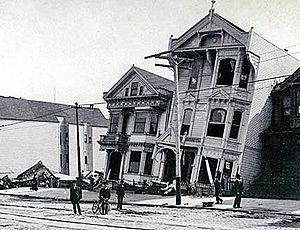

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake was a big earthquake that hit San Francisco on April 18, 1906. It was felt from Los Angeles to Oregon and Nevada. The earthquake was about a 7.8 on the Richter scale. Around 3,000 people were killed and between 227,000 and 300,000 people were left homeless.

There were also fires because gas pipes were destroyed, and the gas caught on fire. The mayor had an idea that if some buildings were dynamite destroyed, than they wouldn’t spread fire. He was wrong. The firestorm raged through the city at an alarming pace.

Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the earthquake and fires that came later. The city is on the San Andreas Fault, which slid, causing the earthquake. Many people looted so then the Army had to come in to keep the peace, but there were reports of the army looting as well.

Contents

Impact

At the time, 375 deaths were reported. Partly because hundreds of fatalities in Chinatown went ignored and unrecorded, the total number of deaths is still uncertain today, and is estimated to be roughly 3,000 at minimum. Most of the deaths occurred in San Francisco itself, but 189 were reported elsewhere in the Bay Area; nearby cities, such as Santa Rosa and San Jose, also suffered severe damage. In Monterey County, the earthquake permanently shifted the course of the Salinas River near its mouth. Where previously the river emptied into Monterey Bay between Moss Landing and Watsonville, it was diverted 6 miles south to a new outlet just north of Marina.

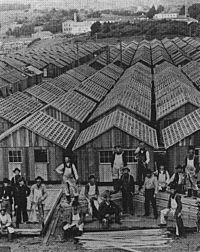

Between 227,000 and 300,000 people were left homeless out of a population of about 410,000; half of the people who evacuated fled across the bay to Oakland and Berkeley. Newspapers at the time described Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, the Panhandle and the beaches between Ingleside and North Beach as being covered with makeshift tents. More than two years later, many of these refugee camps were still in full operation.

The earthquake and fire left long-standing and significant pressures on the development of California. At the time of the disaster, San Francisco had been the ninth-largest city in the United States and the largest on the West Coast, with a population of about 410,000. Over a period of 60 years, the city had become the financial, trade and cultural center of the West; operated the busiest port on the West Coast; and was the "gateway to the Pacific", through which growing U.S. economic and military power was projected into the Pacific and Asia. Over 80% of the city was destroyed by the earthquake and fire. Though San Francisco rebuilt quickly, the disaster diverted trade, industry and population growth south to Los Angeles, which during the 20th century became the largest and most important urban area in the West. Many of the city's leading poets and writers retreated to Carmel-by-the-Sea where, as "The Barness", they established the arts colony reputation that continues today.

The 1908 Lawson Report, a study of the 1906 quake led and edited by Professor Andrew Lawson of the University of California, showed that the same San Andreas Fault which had caused the disaster in San Francisco ran close to Los Angeles as well. The earthquake was the first natural disaster of its magnitude to be documented by photography and motion picture footage and occurred at a time when the science of seismology was blossoming. The overall cost of the damage from the earthquake was estimated at the time to be around US$400 million ($8.2 billion in 2009 dollars).

- Damage to other towns

Although the impact of the earthquake on San Francisco was the most famous, the earthquake also inflicted considerable damage on several other cities. These include San Jose and Santa Rosa, the entire downtown of which was essentially destroyed.

Magnitude and geology

The most widely accepted estimate for the magnitude of the earthquake is a moment magnitude (Mw) of 7.8; however, other values have been proposed, from 7.7 to as high as 8.25. The main shock epicenter occurred offshore about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the city, near Mussel Rock. Shaking was felt from Oregon to Los Angeles, and inland as far as central Nevada.

The earthquake was caused by a rupture on the San Andreas Fault, a continental transform fault that forms part of the tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate. The fault is characterized by mainly lateral motion in a dextral sense, where the western (Pacific) plate moves northward relative to the eastern (North American) plate. The 1906 rupture propagated both northward and southward for a total of 296 miles (476 km). This fault runs the length of California from the Salton Sea in the south to Cape Mendocino to the north, a distance of about 810 miles (1,300 km). The earthquake ruptured the northern third of the fault for a distance of 296 miles (476 km). The maximum observed surface displacement was about 20 feet (6 m); however, geodetic measurements show displacements of up to 28 feet (8.5 m).

A strong foreshock preceded the mainshock by about 20 to 25 seconds. The strong shaking of the main shock lasted about 42 seconds. The shaking intensity as described on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale reached VIII in San Francisco and up to IX in areas to the north like Santa Rosa where destruction was devastating. There were decades of minor earthquakes – more than at any other time in the historical record for northern California – before the 1906 quake. Widely interpreted previously as precursory activity to the 1906 earthquake, they have been found to have a strong seasonal pattern and have been postulated to be due to large seasonal sediment loads in coastal bays that overlie faults as a result of the erosion caused by hydraulic mining in the later years of the California Gold Rush.

this killed over 2 people

U.S. Army

The city's fire chief, Dennis T. Sullivan, was seriously injured when the earthquake first struck and later died from his injuries. The interim fire chief sent an urgent request to the Presidio, an army post on the edge of the stricken city, for dynamite. General Funston had already decided the situation required the use of troops. Collaring a policeman, he sent word to Mayor Eugene Schmitz of his decision to assist, and then ordered army troops from nearby Angel Island to mobilize and come into the city. Explosives were ferried across the bay from the California Powder Works in what is now Hercules.

During the first few days, soldiers provided valuable services like patrolling streets to discourage looting and guarding buildings such as the U.S. Mint, post office, and county jail. They aided the fire department in dynamiting to demolish buildings in the path of the fires. The army also became responsible for feeding, sheltering, and clothing the tens of thousands of displaced residents of the city. Under the command of Funston's superior, Major General Adolphus Greely, Commanding Officer, Pacific Division, over 4,000 troops saw service during the emergency. On July 1, 1906, civil authorities assumed responsibility for relief efforts, and the army withdrew from the city.

On April 18, in response to riots among evacuees and looting, Mayor Schmitz issued and ordered posted a proclamation that "The Federal Troops, the members of the Regular Police Force and all Special Police Officers have been authorized by me to kill any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime".

Early on April 18, 1906, recently retired Captain Edward Ord of the 22nd Infantry Regiment was appointed a Special Police Officer by Mayor Eugene Schmitz and liasioned with Major General Adolphus Greely for relief work with the 22nd Infantry and other military units involved in the emergency. Ord later wrote a long letter to his mother on the April 20 regarding Schmitz' "Shoot-to-Kill" Order and some "despicable" behavior of certain soldiers of the 22nd Infantry who were looting. He also made it clear that the majority of soldiers served the community well.

Relocation and housing

The army built 5,610 redwood and fir "relief houses" to accommodate 20,000 displaced people. The houses were designed by John McLaren, and were grouped in eleven camps, packed close to each other and rented to people for two dollars per month until rebuilding was completed. They were painted olive drab, partly to blend in with the site, and partly because the military had large quantities of olive drab paint on hand. The camps had a peak population of 16,448 people, but by 1907 most people had moved out. The camps were then re-used as garages, storage spaces or shops. The cottages cost on average $100 to put up. The $2 monthly rents went towards the full purchase price of $50. Most of the shacks have been destroyed, but a small number survived. One of the modest 720 sq ft (67 m2) homes was recently purchased for more than $600,000. The last official refugee camp was closed on June 30, 1908.

Aftermath and reconstruction

Property losses from the disaster have been estimated to be more than $400 million. An insurance industry source tallies insured losses at $235 million, the equivalent to $7.65 billion in 2024 dollars.

Political and business leaders strongly downplayed the effects of the earthquake, fearing loss of outside investment in the city which was badly needed to rebuild. In his first public statement, California governor George C. Pardee emphasized the need to rebuild quickly: "This is not the first time that San Francisco has been destroyed by fire, I have not the slightest doubt that the City by the Golden Gate will be speedily rebuilt, and will, almost before we know it, resume her former great activity". The earthquake itself is not even mentioned in the statement. Fatality and monetary damage estimates were manipulated.

Almost immediately after the quake (and even during the disaster), planning and reconstruction plans were hatched to quickly rebuild the city. Rebuilding funds were immediately tied up by the fact that virtually all the major banks had been sites of the conflagration, requiring a lengthy wait of seven-to-ten days before their fire-proof vaults could cool sufficiently to be safely opened. The Bank of Italy, however, had evacuated its funds and was able to provide liquidity in the immediate aftermath. Its president also immediately chartered and financed the sending of two ships to return with shiploads of lumber from Washington and Oregon mills which provided the initial reconstruction materials and surge. In 1929, Bank of Italy was renamed and is now known as Bank of America.

William James, the pioneering American psychologist, was teaching at Stanford at the time of the earthquake and traveled into San Francisco to observe first-hand its aftermath. He was most impressed by the positive attitude of the survivors and the speed with which they improvised services and created order out of chaos. This formed the basis of the chapter "On some Mental Effects of the Earthquake" in his book Memories and Studies.

H. G. Wells had just arrived in New York on his first visit to America when he learned, at lunch, of the San Francisco earthquake. What struck him about the reaction of those around him was that "it does not seem to have affected any one with a sense of final destruction, with any foreboding of irreparable disaster. Every one is talking of it this afternoon, and no one is in the least degree dismayed. I have talked and listened in two clubs, watched people in cars and in the street, and one man is glad that Chinatown will be cleared out for good; another's chief solicitude is for Millet's 'Man with the Hoe.' 'They'll cut it out of the frame,' he says, a little anxiously. 'Sure.' But there is no doubt anywhere that San Francisco can be rebuilt, larger, better, and soon. Just as there would be none at all if all this New York that has so obsessed me with its limitless bigness was itself a blazing ruin. I believe these people would more than half like the situation."

The grander of citywide reconstruction schemes required investment from Eastern monetary sources, hence the spin and de-emphasis of the earthquake, the promulgation of the tough new building codes, and subsequent reputation sensitive actions such as the official low death toll. One of the more famous and ambitious plans came from famed urban planner Daniel Burnham. His bold plan called for, among other proposals, Haussmann-style avenues, boulevards, arterial thoroughfares that radiated across the city, a massive civic center complex with classical structures, and what would have been the largest urban park in the world, stretching from Twin Peaks to Lake Merced with a large atheneum at its peak. But this plan was dismissed at the time as impractical and unrealistic.

For example, real estate investors and other land owners were against the idea due to the large amount of land the city would have to purchase to realize such proposals. City fathers likewise attempted at the time to eliminate the Chinese population and export Chinatown (and other poor populations) to the edge of the county where the Chinese could still contribute to the local taxbase. The Chinese occupants had other ideas and prevailed instead. Chinatown was rebuilt in the newer, modern, Western form that exists today. The destruction of City Hall and the Hall of Records enabled thousands of Chinese immigrants to claim residency and citizenship, creating a backdoor to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and bring in their relatives from China.

While the original street grid was restored, many of Burnham's proposals inadvertently saw the light of day, such as a neoclassical civic center complex, wider streets, a preference of arterial thoroughfares, a subway under Market Street, a more people-friendly Fisherman's Wharf, and a monument to the city on Telegraph Hill, Coit Tower.

The earthquake was also responsible for the development of the Pacific Heights neighborhood. The immense power of the earthquake had destroyed almost all of the mansions on Nob Hill except for the Flood Mansion. Others that hadn't been destroyed were dynamited by the Army forces aiding the firefighting efforts in attempts to create firebreaks. As one indirect result, the wealthy looked westward where the land was cheap and relatively undeveloped, and where there were better views and a consistently warmer climate. Constructing new mansions without reclaiming and clearing old rubble simply sped attaining new homes in the tent city during the reconstruction. In the years after the first world war, the "money" on Nob Hill migrated to Pacific Heights, where it has remained to this day.

Reconstruction was swift, and largely completed by 1915, in time for the Panama-Pacific Exposition which celebrated the reconstruction of the city and its "rise from the ashes".

Since 1915, the city has officially commemorated the disaster each year by gathering the remaining survivors at Lotta's Fountain, a fountain in the city's financial district that served as a meeting point during the disaster for people to look for loved ones and exchange information.

Images for kids

-

Arnold Genthe's photograph, looking toward the fire on Sacramento Street

-

The Agassiz statue in front of the Zoology building (now building 420), Stanford University

See also

In Spanish: Terremoto de San Francisco de 1906 para niños

In Spanish: Terremoto de San Francisco de 1906 para niños