Richea sprengelioides facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Richea sprengelioides |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Richea sprengelioides in Walls of Jerusalem National Park |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Richea

|

| Species: |

sprengelioides

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Cystanthe sprengelioides R.Br. |

|

Richea sprengelioides is a species of flowering plant in the family Ericaceae. It is one of the 11 species within the genus Richea that are endemic to Australia, of which 9 are found only in Tasmania.

The species was first formally described by botanist Robert Brown in 1810 in Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae. He gave it the name Cystanthe sprengelioides.[2] In 1867 Victorian Government Botanist Ferdinand von Mueller transferred the species to the genus Richea.

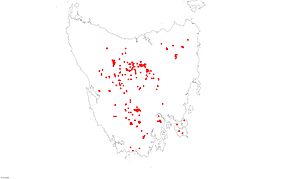

It is found throughout the mountainous regions of Tasmania.

Description

Richea sprengelioides can grow as an erect shrub up to 1.2m in height. Older stems are devoid of leaves but bear numerous angular scars. Its leaves follow the distinctive habit of its genus, sheathing the stem before curling away and tapering to a point. Its inflorescence is roughly 2 centimeters wide and tall, with some 20 flowers clustered together at the end of the stems.

Richea sprengelioides in general is easily identified though it may be confused with a couple of other species found in Tasmania. One of the main features that distinguish R. sprengelioides from others in its genus is the size of its leaves, which at 8–12 mm are substantially smaller than those of Richea scoparia (a species that is often found growing in the same habitat). Its closest relative, R. procera, is found at lower altitudes (over 400m above sea level) but it largely disappears before the sub alpine zone where R. sprengelioides is most common. These two species do however co-occur at mid altitudes and their resemblance has led some to suggest that they simply represent clinal variation within the same species . These species can, however, be distinguished by their flowers. R. sprengelioides has creamy white flowers while those of R. procera have a pink tip. The most distinct difference between these two species is their filaments, which are white, smooth and slender in R. sprengelioides as opposed to R. procera which has yellow, thickened and papillose filaments. Lastly Sprengelia incarnata, a far more distant relative, looks very similar to R. sprengelioides. The two species may however be distinguished by leaf scars which are visible on the stem of R. sprengelioides but are absent from that of S. incarnata.

Habitat and distribution

Richea sprengelioides is found throughout the mountainous regions of west, south-west, north-east and the central plateau of Tasmania. It is most common in alpine areas where is most often encountered growing as a small bush within the dominant shrub layer, this, however, does vary with exposure and it can be found growing in a much reduced form within alpine herbfields. At lower altitudes it is sometimes seen growing in exposed rocky sites and less often within well drained woodland. The flowers are sought out and eaten by a number of mammal species.

Diversity and endemism

Richea sprengelioides is one of 11 species within its genus that are endemic to Australia of which 9 are found only in Tasmania. The relative abundance of the genus Richea within Tasmania raises the question of why there are so few elsewhere. Two theories have been put forward to explain this. Firstly that the Tasmanian species are paleoendemic and of Gondwanan origin. This implies that since the breakup of Gondwana conditions elsewhere have become hostile, to the point that Tasmanian species have survived where others have largely died out. A second possibility is that these species are relatively young, having diverged since the breakup of Gondwana. This implies that the genus has as yet been unable to disperse beyond south eastern Australia.

Threats and conservation

Richea sprengelioides is widely found throughout Tasmania and much of its habitat is protected. While this species is not listed by the IUCN, alpine heathland, in which it is most commonly found, has the potential to change rapidly in the coming decades as Tasmania's climate warms. These higher altitude ecosystems contain some of the highest rates of endemism in the Tasmania so changes here are of particular concern.