Red-breasted merganser facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Red-breasted merganser |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male in winter at New Jersey, United States | |

|

|

| Female, New York, United States | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Mergus

|

| Species: |

serrator

|

|

|

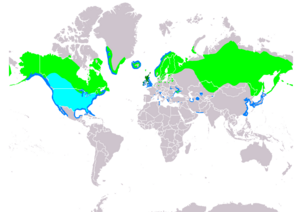

| Red-breasted merganser range Breeding Resident Non-breeding Passage | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator) is a duck species that is native to much of the Northern Hemisphere. The red breast that gives the species its common name is only displayed by males in breeding plumage. Individuals fly rapidly, and feed by diving from the surface to pursue aquatic animals underwater, using serrated bills to capture slippery fish. They migrate each year from breeding sites on lakes and rivers to their mostly coastal wintering areas, making them the only species in the genus Mergus to frequent saltwater. They form flocks outside of breeding season that are usually small but can reach 100 individuals. The worldwide population of this species is stable, though it is threatened in some areas by habitat loss and other factors.

Contents

Etymology

The genus name Mergus is a Latin word used by Pliny and other Roman authors to refer to an unspecified water bird. The specific epithet serrator is Latin for sawyer and is ultimately from serra, meaning saw. It refers to the saw-like projections on the bird's bill, which enable it to hold on to slippery fish, its most frequent prey.

The red-breasted merganser was one of the many bird species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae, where it was given the binomial name Mergus serrator.

Description

The adult red-breasted merganser is 51–64 cm (20–25 in) long, has a wingspan of 66–74 cm (26–29 in), and weighs 800–1,350 g (28–48 oz).

It has a spiky crest and long thin red bill with serrated edges. The male has a dark head with a green sheen, a white neck with a rusty breast, a black back, and white underparts. Adult females have a rusty head and a grayish body. Juveniles look similar to females, but lack the white collar and have smaller white wing patches.

The range of the red-breasted merganser broadly overlaps with that of the similar and closely related common merganser. The two species can therefore occur in the same place at the same time, though the species often choose different habitats (only the red-breasted frequents saltwater). Breeding male plumages are fairly distinctive, but other plumages such as those born by females, immatures, and non-breeding males can make the two species hard to distinguish. The common merganser displays more contrast between the darker head and lighter breast and has a light chin patch not seen on the red-breasted.

Voice

During courtship, the female gives a rasping prrak prrak, while the male gives a catlike meow. In flight, the female makes a harsh gruk. At other times this species is largely silent.

Behaviour

Food and feeding

Red-breasted mergansers dive and swim underwater. They mainly eat small fish, but also consume aquatic insects, worms, crustaceans, and amphibians.

Breeding

Its breeding habitat is freshwater lakes and rivers across northern North America, Greenland, Europe, and the Palearctic. It nests in sheltered locations on the ground near water. It is migratory and many northern breeders winter in coastal waters further south. Outside of the breeding season, it forms flocks that can reach 100 individuals, though these flocks are smaller during spring migration than they are in autumn migration and in winter.

Speed record

The fastest duck ever recorded was a red-breasted merganser that attained a top airspeed of 100 mph (160 km/h) while being pursued by an airplane. This eclipsed the previous speed record held by a canvasback clocked at 72 mph (116 km/h).

Conservation

The red-breasted merganser is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies. The species is also considered a game bird under the Migratory Bird Treaty between the United States and Canada. This means that the species gets some protection, though hunting it is legal in North America in certain seasons and places determined by local hunting regulations. However, few hunters are interested in the species and relatively few birds are harvested.

The species is widespread and common enough to be categorized as least concern by the IUCN, though populations in some areas may be declining. Threats include habitat loss through wetland destruction, exposure to toxins such as pesticides and lead, and becoming bycatch of commercial fishing operations. Anglers and fish farmers have also persecuted the species, which they regard as a competitor, though the impact of this on the species' population is not known.

Gallery