Raccoon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Common raccoon (or racoon) |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Procyon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Procyon lotor |

|

|

|

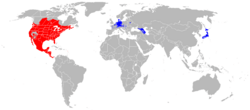

| Common raccoon native range in red, feral range in blue |

|

The raccoon (Procyon lotor, common raccoon, or coon) is a mammal. They are curious, clever, and solitary. Orginally from North America, they have spread through Central America, and live in various habitats. They have escaped in some parts of Eurasia (see map), and now live there as well. They are omnivorous. Its family is in the Caniformia, and related to the mustelids.

The raccoon's most distinctive features are its multi-purpose front paws, its facial 'mask', and its striped tail. Raccoons are noted for their intelligence. Studies show they are able to remember the solution to tasks for up to three years. Raccoons are usually nocturnal. Their food is about 40% invertebrates, 33% plant foods, and 27% vertebrates.

Most raccoons live in the wild. Being around humans does not bother them. They often nest in empty buildings, garages, sheds, and even the attics of houses. Raccoons do not hibernate in the winter. Those that live farther north, where it is colder, grow thick coats to keep them warm and spend long periods sleeping. Raccoons in captivity can live up to 20 years. In the wild, they usually live only 1-3 years.

Two other species of raccoon, the crab-eating raccoon (P. cancrivorus) and the Cozumel Island raccoon (P. pygmaeus) are extremely similar to the common raccoon. The crab-eating raccoon is quite widespread in eastern South America.

Contents

Taxonomy

In the first decades after its discovery by the members of the expedition of Christopher Columbus, who were the first Europeans to leave a written record about the species, taxonomists thought the raccoon was related to many different species, including dogs, cats, badgers and particularly bears. Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, placed the raccoon in the genus Ursus, first as Ursus cauda elongata ("long-tailed bear") in the second edition of his Systema Naturae (1740), then as Ursus Lotor ("washer bear") in the tenth edition (1758–59). In 1780, Gottlieb Conrad Christian Storr placed the raccoon in its own genus Procyon, which can be translated as either "before the dog" or "doglike". It is also possible that Storr had its nocturnal lifestyle in mind and chose the star Procyon as eponym for the species.

Evolution

Based on fossil evidence from Russia and Bulgaria, the first known members of the family Procyonidae lived in Europe in the late Oligocene about 25 million years ago. Similar tooth and skull structures suggest procyonids and weasels share a common ancestor, but molecular analysis indicates a closer relationship between raccoons and bears. After the then-existing species crossed the Bering Strait at least six million years later in the early Miocene, the center of its distribution was probably in Central America. Coatis (Nasua and Nasuella) and raccoons (Procyon) have been considered to share common descent from a species in the genus Paranasua present between 5.2 and 6.0 million years ago. This assumption, based on morphological comparisons of fossils, conflicts with a 2006 genetic analysis which indicates raccoons are more closely related to ringtails. Unlike other procyonids, such as the crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus), the ancestors of the common raccoon left tropical and subtropical areas and migrated farther north about 2.5 million years ago, in a migration that has been confirmed by the discovery of fossils in the Great Plains dating back to the middle of the Pliocene. Its most recent ancestor was likely Procyon rexroadensis, a large Blancan raccoon from the Rexroad Formation characterized by its narrow back teeth and large lower jaw.

Subspecies

As of 2005, Mammal Species of the World recognizes 22 subspecies of raccoons. Four of these subspecies living only on small Central American and Caribbean islands were often regarded as distinct species after their discovery. These are the Bahamian raccoon and Guadeloupe raccoon, which are very similar to each other; the Tres Marias raccoon, which is larger than average and has an angular skull; and the extinct Barbados raccoon. Studies of their morphological and genetic traits in 1999, 2003 and 2005 led all these island raccoons to be listed as subspecies of the common raccoon in Mammal Species of the World's third edition. A fifth island raccoon population, the Cozumel raccoon, which weighs only 3 to 4 kg (6.6 to 8.8 lb) and has notably small teeth, is still regarded as a separate species.

The four smallest raccoon subspecies, with a typical weight of 1.8 to 2.7 kg (4.0 to 6.0 lb), live along the southern coast of Florida and on the adjacent islands; an example is the Ten Thousand Islands raccoon (Procyon lotor marinus). Most of the other 15 subspecies differ only slightly from each other in coat color, size and other physical characteristics. The two most widespread subspecies are the eastern raccoon (Procyon lotor lotor) and the Upper Mississippi Valley raccoon (Procyon lotor hirtus). Both share a comparatively dark coat with long hairs, but the Upper Mississippi Valley raccoon is larger than the eastern raccoon. The eastern raccoon occurs in all U.S. states and Canadian provinces to the north of South Carolina and Tennessee. The adjacent range of the Upper Mississippi Valley raccoon covers all U.S. states and Canadian provinces to the north of Louisiana, Texas and New Mexico.

The taxonomic identity of feral raccoons inhabiting Central Europe, Causasia and Japan is unknown, as the founding populations consisted of uncategorized specimens from zoos and fur farms.

| Subspecies | Image | Trinomial authority | Description | Range | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern raccoon P. l. lotor Nominate subspecies |

|

Linnaeus, 1758 | A small and dark subspecies with long, soft fur. | Nova Scotia, southern New Brunswick, southern Quebec, and southern Ontario south through the eastern United States to North Carolina, and from the Atlantic coast west to Lake Michigan, Indiana, southern Illinois, western Kentucky, and probably eastern Tennessee. | annulatus (G. Fischer, 1814) brachyurus (Wiegmann, 1837) |

| Key Vaca raccoon P. l. auspicatus |

Nelson, 1930 | A very small and pale-furred subspecies. | Key Vaca and doubtless closely adjoining keys of the Key Vaca Group, a central section of the main chain off the southern coast of Florida. | ||

| Florida raccoon P. l. elucus |

|

Bangs, 1898 | Generally a medium-sized and dark-colored subspecies with a prominent rusty rufous nuchal patch. | Peninsular Florida, except southwestern part inhabited by P. l. marinus, north to extreme southern Georgia; grading into P. l. varius in northwest Florida. | |

| Snake River Valley raccoon P. l. excelsus |

|

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | A very large and pale subspecies. | Snake River drainage in southeastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and southern Idaho, the Humboldt River Valley, Nev., and river valleys of northeastern California. | |

| Texas raccoon P. l. fuscipes |

Mearns, 1914 | A large, dark grayish subspecies. | Texas, except extreme northern and western parts, southern Arkansas, Louisiana, except delta region of Mississippi, and south into northeastern Mexico, including Coahuila and Nuevo León, to southern Tamaulipas. | ||

| † Barbados raccoon P. l. gloveralleni |

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | A small, dark-furred subspecies with a lightly built skull. | Known only from the Island of Barbados. | solutus (Nelson and Goldman, 1931) | |

| Baja California raccoon P. l. grinnelli |

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | A large, pale-furred subspecies with high and broad skull. | Southern Baja California from the Cape region north at least to San Ignacio. | ||

| Mexican plateau raccoon P. l. hernandezii |

|

Wagler, 1831 | A large and dark grayish subspecies with a flattish skull and heavy dentition. | Southern part of tableland or plateau region of Mexico and adjoining coasts, from Nayarit, Jalisco, and San Luis Potosí, south to near the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. | crassidens (Hollister, 1914) dickeyi (Nelson and Goldman, 1931) |

| Upper Mississippi Valley raccoon P. l. hirtus |

|

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | A large and dark-furred subspecies, whose pelage is usually suffused with ochraceous buff. | Upper Mississippi and Missouri River drainage areas from the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains east to Lake Michigan, and from southern Manitoba and probably southwestern Ontario and southeastern Alberta south to southern Oklahoma and Arkansas. | |

| Torch Key raccoon P. l. incautus |

|

Nelson, 1930 | A small subspecies with very pale fur (the palest of the Florida raccoons). | Big Pine Key Group, near southwestern end of chain of Florida Keys. | |

| Matecumbe Key raccoon P. l. inesperatus |

Nelson, 1930 | Similar to P. l. elucus, but smaller and grayer and with a flatter skull. | Key Largo Group, embracing fringing keys along the south-east coast of Florida, from Virginia Key south to Lower Matecumbe Key. | ||

| Tres Marias raccoon P. l. insularis |

|

Merriam, 1898 | A large, massive-skulled subspecies with short and coarse fur. | Tres Marías Islands, off west coast of Nayarit, Mexico. | vicinus (Nelson and Goldman, 1931) |

| Saint Simon Island raccoon P. l. litoreus |

|

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | Similar to P. l. elucus, being of medium size and having dark fur. | Coastal strip and islands of Georgia. | |

| Ten Thousand Islands raccoon P. l. marinus |

Nelson, 1930 | A very small subspecies with heavy dentition. | Keys of the Ten Thousand Islands Group, and adjoining mainland of southwestern Florida from Cape Sable north through the Everglades to Lake Okeechobee. | maritimus (Dozier, 1948) | |

| Bahamian raccoon P. l. maynardi |

|

Bangs, 1898 | A small and slightly dark subspecies with a lightly built skull and dentition. | Known only from New Providence Island, Bahamas. | flavidus (de Beaux, 1910) minor (Miller, 1911) |

| Mississippi Delta raccoon P. l. megalodous |

Lowery, 1943 | A medium-sized subspecies, with a massive skull and pale yellow fur suffused above with black. | Coast region of southern Louisiana from St. Bernard Parish west to Cameron Parish. | ||

| Pacific Northwest raccoon P. l. pacificus |

Merriam, 1899 | A dark-furred subspecies with a relatively broad, flat skull. | Southwestern British Columbia, except Vancouver Island, northern, central, and western Washington, western Oregon, and extreme northwestern California. | proteus (Brass, 1911) | |

| Colorado Desert raccoon P. l. pallidus |

Merriam, 1900 | One of the palest subspecies, around the same size as P. l. mexicanus. | Colorado and Gila River Valleys and adjoining territory from the delta north to northeastern Utah, and east to western Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. | ochraceus (Mearns, 1914) | |

| California raccoon P. l. psora |

|

Gray, 1842 | A large and moderately dark subspecies with a broad, rather flat skull. | California, except extreme northwest coastal strip, the northeastern corner and southeastern desert region, ranging south through northwestern Baja California to San Quintin; extreme westcentral Nevada. | californicus (Means, 1914) |

| Isthmian raccoon P. l. pumilus |

|

Miller, 1911 | Similar to P. l. crassidens in color, but has a shorter, broader and flatter skull. | Panama and the Canal Zone from Porto Bello west to Boqueron, Chiriqui, though the limits of its range are unknown. | |

| † Short-faced raccoon P. l. simus |

|

Gidley, 1906 | A Pleistocene subspecies similar to P. l. excelsus, but with a deeper lower jaw and a more robust dentition. | California. | |

| Vancouver Island raccoon P. l. vancouverensis |

Nelson and Goldman, 1930 | A dark-furred subspecies, similar to P. l. pacificus but smaller. | Known only from Vancouver Island. |

Description

Physical characteristics

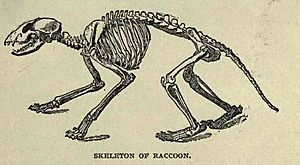

Head to hindquarters, raccoons measure between 40 and 70 cm (16 and 28 in), not including the bushy tail which can measure between 20 and 40 cm (8 and 16 in), but is usually not much longer than 25 cm (10 in). The shoulder height is between 23 and 30 cm (9 and 12 in). The body weight of an adult raccoon varies considerably with habitat, making the raccoon one of the most variably sized mammals. It can range from 5 to 26 kilograms (10 to 60 lb), but is usually between 5 and 12 kilograms (10 and 30 lb). The smallest specimens live in southern Florida, while those near the northern limits of the raccoon's range tend to be the largest (see Bergmann's rule). Males are usually 15 to 20% heavier than females. At the beginning of winter, a raccoon can weigh twice as much as in spring because of fat storage. The largest recorded wild raccoon weighed 28.4 kg (62.6 lb) and measured 140 cm (55 in) in total length, by far the largest size recorded for a procyonid.

The most characteristic physical feature of the raccoon is the area of black fur around the eyes, which contrasts sharply with the surrounding white face coloring. This is reminiscent of a "bandit's mask" and has thus enhanced the animal's reputation for mischief. The slightly rounded ears are also bordered by white fur. Raccoons are assumed to recognize the facial expression and posture of other members of their species more quickly because of the conspicuous facial coloration and the alternating light and dark rings on the tail. The dark mask may also reduce glare and thus enhance night vision. On other parts of the body, the long and stiff guard hairs, which shed moisture, are usually colored in shades of gray and, to a lesser extent, brown. Raccoons with a very dark coat are more common in the German population because individuals with such coloring were among those initially released to the wild. The dense underfur, which accounts for almost 90% of the coat, insulates against cold weather and is composed of 2 to 3 cm (0.8 to 1.2 in) long hairs.

The raccoon, whose method of locomotion is usually considered to be plantigrade, can stand on its hind legs to examine objects with its front paws. As raccoons have short legs compared to their compact torso, they are usually not able either to run quickly or jump great distances. Their top speed over short distances is 16 to 24 km/h (10 to 15 mph). Raccoons can swim with an average speed of about 5 km/h (3 mph) and can stay in the water for several hours. For climbing down a tree headfirst—an unusual ability for a mammal of its size—a raccoon rotates its hind feet so they are pointing backwards. Raccoons have a dual cooling system to regulate their temperature; that is, they are able to both sweat and pant for heat dissipation.

Senses

The most important sense for the raccoon is its sense of touch. The "hyper sensitive" front paws are protected by a thin horny layer that becomes pliable when wet. The five digits of the paws have no webbing between them, which is unusual for a carnivoran. Almost two-thirds of the area responsible for sensory perception in the raccoon's cerebral cortex is specialized for the interpretation of tactile impulses, more than in any other studied animal. They are able to identify objects before touching them with vibrissae located above their sharp, nonretractable claws. The raccoon's paws lack an opposable thumb; thus, it does not have the agility of the hands of primates. There is no observed negative effect on tactile perception when a raccoon stands in water below 10 °C (50 °F) for hours.

Raccoons are thought to be color blind or at least poorly able to distinguish color, though their eyes are well-adapted for sensing green light. Although their accommodation of 11 dioptre is comparable to that of humans and they see well in twilight because of the tapetum lucidum behind the retina, visual perception is of subordinate importance to raccoons because of their poor long-distance vision. In addition to being useful for orientation in the dark, their sense of smell is important for intraspecific communication. Glandular secretions (usually from their anal glands), urine and feces are used for marking. With their broad auditory range, they can perceive tones up to 50–85 kHz as well as quiet noises, like those produced by earthworms underground.

Intelligence

Zoologist Clinton Hart Merriam described raccoons as "clever beasts", and that "in certain directions their cunning surpasses that of the fox." Only a few studies have been undertaken to determine the mental abilities of raccoons, most of them based on the animal's sense of touch. In a study by the ethologist H. B. Davis in 1908, raccoons were able to open 11 of 13 complex locks in fewer than 10 tries and had no problems repeating the action when the locks were rearranged or turned upside down. Davis concluded they understood the abstract principles of the locking mechanisms and their learning speed was equivalent to that of rhesus macaques.

Studies in 1963, 1973, 1975 and 1992 concentrated on raccoon memory showed they can remember the solutions to tasks for at least three years.

Behavior

Social behavior

Studies in the 1990s by the ethologists Stanley D. Gehrt and Ulf Hohmann suggest that raccoons engage in gender-specific social behaviors and are not typically solitary, as was previously thought. Related females often live in a so-called "fission-fusion society"; that is, they share a common area and occasionally meet at feeding or resting grounds. Unrelated males often form loose male social groups to maintain their position against foreign males during the mating season—or against other potential invaders. Such a group does not usually consist of more than four individuals. Since some males show aggressive behavior towards unrelated kits, mothers will isolate themselves from other raccoons until their kits are big enough to defend themselves.

With respect to these three different modes of life prevalent among raccoons, Hohmann called their social structure a "three-class society". Samuel I. Zeveloff, professor of zoology at Weber State University and author of the book Raccoons: A Natural History, is more cautious in his interpretation and concludes at least the females are solitary most of the time and, according to Erik K. Fritzell's study in North Dakota in 1978, males in areas with low population densities are solitary as well.

The shape and size of a raccoon's home range varies depending on age, sex, and habitat, with adults claiming areas more than twice as large as juveniles. While the size of home ranges in the habitat of North Dakota's prairies lie between 7 and 50 km2 (3 and 20 sq mi) for males and between 2 and 16 km2 (1 and 6 sq mi) for females, the average size in a marsh at Lake Erie was 0.5 km2 (0.19 sq mi). Irrespective of whether the home ranges of adjacent groups overlap, they are most likely not actively defended outside the mating season if food supplies are sufficient. Odor marks on prominent spots are assumed to establish home ranges and identify individuals. Urine and feces left at shared raccoon latrines may provide additional information about feeding grounds, since raccoons were observed to meet there later for collective eating, sleeping and playing.

Concerning the general behavior patterns of raccoons, Gehrt points out that "typically you'll find 10 to 15 percent that will do the opposite" of what is expected.

Diet

Though usually nocturnal, the raccoon is sometimes active in daylight to take advantage of available food sources. Its diet consists of about 40% invertebrates, 33% plant material and 27% vertebrates.

While its diet in spring and early summer consists mostly of insects, worms, and other animals already available early in the year, it prefers fruits and nuts, such as acorns and walnuts, which emerge in late summer and autumn, and represent a rich calorie source for building up fat needed for winter. Contrary to popular belief, raccoons only occasionally eat active or large prey, such as birds and mammals. They prefer prey that is easier to catch, specifically fish, amphibians and bird eggs. Raccoons are virulent predators of eggs and hatchlings in both birds and reptile nests, to such a degree that, for threatened prey species, raccoons may need to removed from the area or nests may need to be relocated to mitigate the effect of their predations (i.e. in the case of some globally threatened turtles).

When food is plentiful, raccoons can develop strong individual preferences for specific foods. In the northern parts of their range, raccoons go into a winter rest, reducing their activity drastically as long as a permanent snow cover makes searching for food impossible.

Dousing

One aspect of raccoon behavior is so well known that it gives the animal part of its scientific name, Procyon lotor; "lotor" is neo-Latin for "washer". In the wild, raccoons often dabble for underwater food near the shore-line. They then often pick up the food item with their front paws to examine it and rub the item, sometimes to remove unwanted parts. This gives the appearance of the raccoon "washing" the food. The tactile sensitivity of raccoons' paws is increased if this rubbing action is performed underwater, since the water softens the hard layer covering the paws. However, the behavior observed in captive raccoons in which they carry their food to water to "wash" or douse it before eating has not been observed in the wild. Naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, believed that raccoons do not have adequate saliva production to moisten food thereby necessitating dousing, but this hypothesis is now considered to be incorrect. Captive raccoons douse their food more frequently when a watering hole with a layout similar to a stream is not farther away than 3 m (10 ft).

Reproduction

During the mating season, males restlessly roam their home ranges in search of females in an attempt to court them.

After usually 63 to 65 days of gestation (although anywhere from 54 to 70 days is possible), a litter of typically two to five young is born. The average litter size varies widely with habitat, ranging from 2.5 in Alabama to 4.8 in North Dakota. Larger litters are more common in areas with a high mortality rate, due, for example, to hunting or severe winters.

The kits (also called "cubs") are blind and deaf at birth, but their mask is already visible against their light fur. The birth weight of the about 10 cm (4 in)-long kits is between 60 and 75 g (2.1 and 2.6 oz). Their ear canals open after around 18 to 23 days, a few days before their eyes open for the first time. Once the kits weigh about 1 kg (2 lb), they begin to explore outside the den, consuming solid food for the first time after six to nine weeks. After this point, their mother suckles them with decreasing frequency; they are usually weaned by 16 weeks. In the fall, after their mother has shown them dens and feeding grounds, the juvenile group splits up. While many females will stay close to the home range of their mother, males can sometimes move more than 20 km (12 mi) away.

Life expectancy

Captive raccoons have been known to live for more than 20 years. However, the species' life expectancy in the wild is only 1.8 to 3.1 years, depending on the local conditions in terms of traffic volume, hunting, and weather severity.

Range

Habitat

Although they have thrived in sparsely wooded areas in the last decades, raccoons depend on vertical structures to climb when they feel threatened. Therefore, they avoid open terrain and areas with high concentrations of beech trees, as beech bark is too smooth to climb. Tree hollows in old oaks or other trees and rock crevices are preferred by raccoons as sleeping, winter and litter dens. If such dens are unavailable or accessing them is inconvenient, raccoons use burrows dug by other mammals, dense undergrowth or tree crotches. In a study in the Solling range of hills in Germany, more than 60% of all sleeping places were used only once, but those used at least ten times accounted for about 70% of all uses. Since amphibians, crustaceans, and other animals around the shore of lakes and rivers are an important part of the raccoon's diet, lowland deciduous or mixed forests abundant with water and marshes sustain the highest population densities. While population densities range from 0.5 to 3.2 animals per square kilometer (1.3 to 8.3 animals per square mile) in prairies and do not usually exceed 6 animals per square kilometer (15.5 animals per square mile) in upland hardwood forests, more than 20 raccoons per square kilometer (51.8 animals per square mile) can live in lowland forests and marshes.

Images for kids

-

An albino Florida raccoon (P. l. elucus) in Virginia Key, Florida

-

A skunk and a California raccoon (P. l. psora) share cat food morsels in a Hollywood, California, backyard

-

A Florida raccoon (P. l. elucus) in the Everglades approaches a group of humans, hoping to be fed.

-

Stylized raccoon skin as depicted on the Raccoon Priests gorget found at Spiro Mounds

See also

In Spanish: Mapache boreal para niños

In Spanish: Mapache boreal para niños