Population decline facts for kids

Population decline, also known as depopulation, is a reduction in a human population size. Throughout history, Earth's total human population has continued to grow; however, current projections suggest that this long-term trend of steady population growth may be coming to an end.

From antiquity until the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the global population grew very slowly, at about 0.04% per year. After about 1800, the growth rate accelerated to a peak of 2.1% annually during the 1962–1968 period, but since then, due to the worldwide collapse of the total fertility rate, it has slowed to 0.9% as of 2023. The global growth rate in absolute numbers accelerated to a peak of 92.8 million in 1990, but has since slowed to 64.7 million in 2021.

Long-term projections indicate that the growth rate of the human population of the planet will continue to slow and that before the end of the 21st century, it will reach zero. Examples of this emerging trend are Japan, whose population is currently (2022–2026) declining at the rate of 0.5% per year, and China, whose population has peaked and is currently (2022 – 2026) declining at the rate of about 0.04%. By 2050, Europe's population is projected to be declining at the rate of 0.3% per year.

Population growth has declined mainly due to the abrupt decline in the global total fertility rate, from 5.3 in 1963 to 2.3 in 2021. The decline in the total fertility rate has occurred in every region of the world and is a result of a process known as demographic transition. To maintain its population, ignoring migration, a country requires a minimum fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman of childbearing age (the number is slightly greater than 2 because not all children live to adulthood). However, most societies experience a drastic drop in fertility to well below 2 as they grow more wealthy. The tendency of women in wealthier countries to have fewer children is attributed to a variety of reasons, such as lower infant mortality and a reduced need for children as a source of family labor or retirement welfare, both of which reduce the incentive to have many children. Better access to education for young women, which broadens their job prospects, is also often cited.

Possible consequences of long-term national population decline can be net negative or positive. If a country can increase its workforce productivity faster than its population is declining, the results, in terms of its economy, the quality of life of its citizens, and the environment, can be net positive. If it cannot increase workforce productivity faster than its population's decline, the results can be negative.

National efforts to confront a declining population to date have been focused on the possible negative economic consequences and have been centered on increasing the size and productivity of the workforce.

Contents

Causes

A reduction over time in a region's population can be caused by sudden adverse events such as outbursts of infectious disease, famine, and war or by long-term trends, for example, sub-replacement fertility, persistently low birth rates, high mortality rates, and continued emigration.

Short-term population shocks

Historical episodes of short-term human population decline have been common and have been caused by several factors.

High mortality rates caused by:

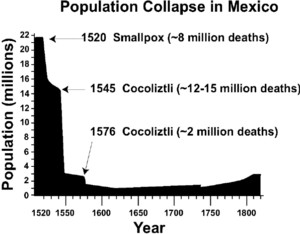

- Disease, for example, the Black Death that devastated Europe in the 14th and 17th centuries, the arrival of Old World diseases in the Americas during European colonization, and the Spanish flu pandemic after World War I,

- Famine, for example, the Great Irish Famine of the 19th century, and the Great Chinese Famine caused by the Great Leap Forward which caused tens of millions of deaths,

- War, for example, the Mongol invasion of Europe in the 13th century, which may have reduced the population of Hungary by 20–40%,

- Civil unrest, for example, the forced migration of the population of Syria because of the Syrian Civil War.

- A combination of these. The first half of the 20th century in Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union was marked by a succession of major wars, famines and other disasters which caused large-scale population losses (approximately 60 million excess deaths).

Less frequently, short-term population declines are caused by genocide or mass execution. For example, it has been estimated that the Armenian genocide caused 1.5 million deaths, the Jewish Holocaust about 6 million, and, in the 1970s, the population of Cambodia declined because of wide-scale executions by the Khmer Rouge.

In modern times, the AIDS pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic have caused short-term drops in fertility and significant excess mortality in a number of countries.

Some population declines result from indeterminate causes, for example, the Bronze Age Collapse, which has been described as the worst disaster in ancient history.

Long-term historic trends in world population growth

In spite of these short-term population shocks, world population has continued to grow. From around 10,000 BC to the beginning of the Early modern period (generally 1500 – 1800), world population grew very slowly, around 0.04% per year. During that period, population growth was governed by conditions now labeled the “Malthusian Trap”.

After 1700, driven by increases in human productivity due to the Industrial Revolution, particularly the increase in agricultural productivity, population growth accelerated to around 0.6% per year, a rate that was over ten times the rate of population growth of the previous 12,000 years. This rapid increase in global population caused Malthus and others to raise the first concerns about overpopulation.

After World War I birth rates in the United States and many European countries fell below replacement level. This prompted concern about population decline. The recovery of the birth rate in most western countries around 1940 that produced the "baby boom", with annual growth rates in the 1.0 – 1.5% range, and which peaked during the period 1962 -1968 at 2.1% per year, temporarily dispelled prior concerns about population decline, and the world was once again fearful of overpopulation.

But after 1968 the global population growth rate started a long decline, and in the period 2022–2027 the UN estimates it to be about 0.9%, less than half of its peak during the period 1962 - 1968. Although still growing, the UN predicts that global population will level out around 2086, and some sources predict the start of a decline before then.

The principal cause of this phenomenon is the abrupt decline in the global total fertility rate, from 5.3 in 1963 to 2.3 in 2021, as the world continues to move through the stages of the Demographic Transition . The decline in the total fertility rate has occurred in every region of the world and has brought renewed concern from some for population decline.

The era of rapid global population increase, and concomitant concern about a population explosion, has been short compared with the span of human history. It began roughly at the beginning of the industrial revolution and appears to be now drawing to a close.

Possible consequences

Predictions of the net economic (and other) effects from a slow and continuous population decline (e.g. due to low fertility rates) are mainly theoretical since such a phenomenon is a relatively new and unprecedented one. The results of many of these studies show that the estimated impact of population growth on economic growth is generally small and can be positive, negative, or nonexistent. A recent meta-study found no relationship between population growth and economic growth.

Possible positive effects

The effects of a declining population can be positive. The single best gauge of economic success is the growth of GDP per person, not total GDP. GDP per person (also known as GDP per capita or per capita GDP) is a rough proxy for average living standards. A country can both increase its average living standard and grow its total GDP even though its population growth is low or even negative. The economies of both Japan and Germany went into recovery around the time their populations began to decline (2003–2006). In other words, both the total and per capita GDP in both countries grew more rapidly after 2005 than before. Russia's economy also began to grow rapidly from 1999 onward, even though its population had been shrinking since 1992–93. Many Eastern European countries have been experiencing similar effects to Russia. Such renewed growth calls into question the conventional wisdom that economic growth requires population growth, or that economic growth is impossible during a population decline.

More recently (2009–2017) Japan has experienced a higher growth of GDP per capita than the United States, even though its population declined over that period. In the United States, the relationship between population growth and growth of GDP per capita has been found to be empirically insignificant. This evidence shows that individual prosperity can grow during periods of population decline.

Attempting to better understand the economic impact of these pluses and minuses, Lee et al. analyzed data from 40 countries. They found that typically fertility well above replacement and population growth would be most beneficial for government budgets. Fertility near replacement and population stability, however, would be most beneficial for standards of living when the analysis includes the effects of age structure on families as well as governments. Fertility moderately below replacement and population decline would maximize per capita consumption when the cost of providing capital for a growing labor force is taken into account.

A focus on productivity growth that leads to an increase in both per capita GDP and total GDP can bring other benefits to:

- the workforce through higher wages, benefits and better working conditions

- customers through lower prices

- owners and shareholders through higher profits

- the environment through more money for investment in more stringent environmental protection

- governments through higher tax proceeds to fund government activities

Another approach to possible positive effects of population decline is to consider Earth's human carrying capacity. Global population decline would begin to counteract the negative effects of human overpopulation. There have been many estimates of Earth's carrying capacity, each generally predicting a high-low range of maximum human population possible. The lowest low estimate is less than one billion, the highest high estimate is over one trillion. A statistical analysis of these historical estimates revealed that the median of high estimates of all of the ranges would be 12 billion, and the median of low estimates would be about 8 billion. According to this analysis, this planet may be entering a zone where its human carrying capacity could be exceeded. However, the large variance in these studies’ estimates diminishes our confidence in them, as such estimates are very difficult to make with current data and methods.

Possible negative effects

The effects of a declining population can also be negative. As a country's population declines, GDP growth may grow even more slowly or may even decline. If the decline in total population is not matched by an equal or greater increase in productivity (GDP/capita), and if that condition continues from one calendar quarter to the next, it follows that a country would experience a decline in GDP, known as an economic recession. If these conditions become permanent, the country could find itself in a permanent recession.

Other possible negative impacts of a declining population are:

- A rise in the dependency ratio which would increase the economic pressure on the workforce

- A loss of culture and the diminishment of trust among citizens

- A crisis in end-of-life care for the elderly because there are insufficient caregivers for them

- Difficulties in funding entitlement programs because there are fewer workers relative to retirees

- A decline in military strength

- A decline in innovation since change comes from the young

- A strain on mental health caused by permanent recession

- Deflation caused by the aging population

All these negative effects could be summarized under the heading of “Underpopulation”. Underpopulation is usually defined as a state in which a country's population has declined too much to support its current economic system.

Population decline can cause internal population pressures that then lead to secondary effects such as ethnic conflict, forced refugee flows, and hyper-nationalism. This is particularly true in regions where different ethnic or racial groups have different growth rates. Low fertility rates that cause long-term population decline can also lead to population aging, an imbalance in the population age structure. Population aging in Europe due to low fertility rates has given rise to concerns about its impact on social cohesion.

A smaller national population can also have geo-strategic effects, but the correlation between population and power is a tenuous one. Technology and resources often play more significant roles. Since World War II, the "static" theory saw a population's absolute size as being one of the components of a country's national power. More recently, the "human capital" theory has emerged. This view holds that the quality and skill level of a labor force and the technology and resources available to it are more important than simply a nation's population size. While there were in the past advantages to high fertility rates, that "demographic dividend" has now largely disappeared.

National efforts to confront declining populations

A country with a declining population will struggle to fund public services such as health care, old age benefits, defense, education, water and sewage infrastructure, etc. To maintain some level of economic growth and continue to improve its citizens’ quality of life, national efforts to confront declining populations will tend to focus on the threat of a declining GDP. Because a country's GDP is dependent on the size and productivity of its workforce, a country confronted with a declining population, will focus on increasing the size and productivity of that workforce.

Increase the size of the workforce

A country's workforce is that segment of its working-age population that is employed. Working age population is generally defined as those people aged 15–64.

Policies that could increase the size of the workforce include:

- Natalism

Natalism is a set of government policies and cultural changes that promote parenthood and encourage women to bear more children. These generally fall into three broad categories:

- Financial incentives. These may include child benefits and other public transfers that help families cover the cost of children.

- Support for parents to combine family and work. This includes maternity-leave policies, parental-leave policies that grant (by law) leaves of absence from work to care for their children, and childcare services.

- Broad social change that encourages children and parenting

For example, Sweden built up an extensive welfare state from the 1930s and onward, partly as a consequence of the debate following "Crisis in the Population Question", published in 1934. Today, (2017) Sweden has extensive parental leave that allows parents to share 16 months of paid leave per child, the cost divided between both employer and State.

Other examples include Romania's natalist policy during the 1967–90 period and Poland's 500+ program.

- Encourage more women to join the workforce.

Encouraging those women in the working-age population who are not working to find jobs would increase the size of the workforce. Female participation in the workforce currently (2018) lags men's in all but three countries worldwide. Among developed countries, the workforce participation gap between men and women can be especially wide. For example, currently (2018), in South Korea 59% of women work compared with 79% of men.

However, even assuming that more women would want to join the workforce, increasing their participation would give these countries only a short-term increase in their workforce, because at some point a participation ceiling is reached, further increases are not possible, and the impact on GDP growth ceases.

- Stop the decline of men in the workforce.

In the United States, the labor force participation of men has been falling since the late 1960s. The labor force participation rate is the ratio between the size of the workforce and the size of the working-age population. In 1969 the labor force participation rate of men in their prime years of 25–54 was 96% and in 2015 was under 89%.

- Raise the retirement age.

Raising the retirement age has the effect of increasing the working-age population, but raising the retirement age requires other policy and cultural changes if it is to have any impact on the size of the workforce:

- Pension reform. Many retirement policies encourage early retirement. For example, in 2018 less than 10% of Europeans between ages 64–74 were employed. Instead of encouraging work after retirement, many public pension plans restrict earnings or hours of work.

- Workplace cultural reform. Employer attitudes towards older workers must change. Extending working lives will require investment in training and working conditions to maintain the productivity of older workers.

One study estimated that increasing the retirement age by 2–3 years per decade between 2010 and 2050 would offset declining working-age populations faced by "old" countries such as Germany and Japan.

- Increase immigration.

A country can increase the size of its workforce by importing more migrants into their working age population. Even if the indigenous workforce is declining, qualified immigrants can reduce or even reverse this decline. However, this policy can only work if the immigrants can join the workforce and if the indigenous population accepts them.

For example, starting in 2019 Japan, a country with a declining workforce, will allow five-year visas for 250,000 unskilled guest workers. Under the new measure, between 260,000 and 345,000 five-year visas will be made available for workers in 14 sectors suffering severe labor shortages, including caregiving, construction, agriculture and shipbuilding.

- Reduce emigration.

The table above shows that long-term persistent emigration, often caused by what is called "Brain Drain", is often one of the major causes of a county's population decline. However, research has also found that emigration can have net positive effects on sending countries, so this would argue against any attempts to reduce it.

Increase the productivity of the workforce

Development economists would call increasing the size of the workforce "extensive growth". They would call increasing the productivity of that workforce "intensive growth". In this case, GDP growth is driven by increased output per worker, and by extension, increased GDP/capita.

In the context of a stable or declining population, increasing workforce productivity is better than mostly short-term efforts to increase the size of the workforce. Economic theory predicts that in the long term, most growth will be attributable to intensive growth, that is, new technology and new and better ways of doing things plus the addition of capital and education to spread them to the workforce.

Increasing workforce productivity through intensive growth can only succeed if workers who become unemployed through the introduction of new technology can be retrained so that they can keep their skills current and not be left behind. Otherwise, the result is technological unemployment. Funding for worker retraining could come from a robot tax, although the idea is controversial.

Long-term future trends

A long-term population decline is typically caused by sub-replacement fertility, coupled with a net immigration rate that fails to compensate for the excess of deaths over births. A long-term decline is accompanied by population aging and creates an increase in the ratio of retirees to workers and children. When a sub-replacement fertility rate remains constant, population decline accelerates over the long term.

Because of the global decline in the fertility rate, projections of future global population show a marked slowing of population growth and the possibility of long-term decline.

The table below summarizes the United Nations projections for future population growth. Any such long-term projections are necessarily highly speculative. The UN divides the world into six regions. Under their projections, during the period 2045–2050, Europe's population will be in decline and all other regions will experience significant reductions in growth; then, by the end of the 21st century (the period 2095–2100) three of these regions will be showing population decline and global population will have peaked and started to decline.

| Region | 2022–27 | 2045–50 | 2095–2100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| Asia | 0.6 | 0.2 | −0.4 |

| Europe | −0.1 | −0.3 | −0.3 |

| Latin America & the Caribbean | 0.7 | 0.2 | −0.5 |

| Northern America | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Oceania | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

| The World | 0.9 | 0.5 | - 0.1 |

Note: the UN's methods for generating these numbers are explained at this reference.

The table shows UN predictions of long-term decline of population growth rates in every region; however, short-term baby booms and healthcare improvements, among other factors, can cause reversals of trends. Population declines in Russia (1994–2008), Germany (1974–1984), and Ireland (1850–1961) have seen long-term reversals. The UK, having seen almost zero growth during the period 1975–1985, is now (2015–2020) growing at 0.6% per year.

See also

- Zero population growth

- Birth dearth

- History of Easter Island#Destruction of society and population

- Human extinction

- Human overpopulation

- Human population planning

- Negative Population Growth

- Political demography

- Population cycle

- Population growth

- Rural flight

- Societal collapse

- Antinatalism